Winged bean

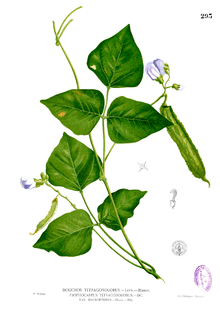

The winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus), also known as the goa bean, four-angled bean, four-cornered bean, manila bean, princess bean, cigarrillas, asparagus bean, dragon bean, is a tropical herbaceous legume plant. Its origin is most likely New Guinea.[1]

| Winged bean | |

|---|---|

| |

| Winged bean flowers, leaves, and seeds | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Tribe: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. tetragonolobus |

| Binomial name | |

| Psophocarpus tetragonolobus | |

It grows abundantly in the hot, humid equatorial countries of South and Southeast Asia. In Southeast Asia and Papua New Guinea it is widely known, but only cultivated on a small scale.[2] Winged bean is widely recognised by farmers and consumers in southern Asia for its variety of uses and disease resistance. Winged bean is nutrient-rich, and all parts of the plant are edible. Leaves can be eaten like spinach, flowers can be used in salads, tubers can be eaten raw or cooked, seeds can be used in similar ways as the soybean. The winged bean is an underutilised species but has the potential to become a major multi-use food crop in the tropics of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.[2]

The winged bean species belongs to the genus Psophocarpus, which is part of the legume family, Fabaceae.[2] Species in the Psophocarpus genus are perennial herbs grown as annuals.[1] Psophocarpus species have tuberous roots and pods with wings.[3] They can climb by twining their stems around a support.

Appearance

The winged bean plant grows as a vine with climbing stems and leaves, 3–4 m (9.8–13.1 ft) in height. It is an herbaceous perennial, but can be grown as an annual. It is generally taller and notably larger than the common bean. The bean pod is typically 15–22 cm (6–8.5 in) long and has four wings with frilly edges running lengthwise. The skin is waxy and the flesh partially translucent in the young pods. When the pod is fully ripe, it turns an ash-brown color and splits open to release the seeds. The large flower is a pale blue. The beans themselves are similar to soybeans in both use and nutritional content (being 29.8% to 39% protein).

The appearance of the winged bean varies abundantly. The shape of its leaves ranges from ovate to deltoid, ovate-lanceolate, lanceolate, and long lanceolate.[2] The green tone of the leaves also varies. The stem, most commonly, is green, but sometimes boasts purple.

The pods are usually rectangular in cross-section, but sometimes appear flat. Pods may be coloured cream, green, pink, or purple. Pods may be smooth are appear smooth or rough, depending on the genotype. Seed shape is often round; oval and rectangular seeds also occur. Seeds may appear white, cream, dark tan, or brown, depending on growing and storage conditions.[2]

Nutritional value

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,711 kJ (409 kcal) |

41.7 g | |

| Dietary fiber | 25.9 g |

16.3 g | |

| Saturated | 2.3 g |

| Monounsaturated | 6 g |

| Polyunsaturated | 4.3 g |

29.65 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 90% 1.03 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 38% 0.45 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 21% 3.09 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 16% 0.795 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 13% 0.175 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 11% 45 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 44% 440 mg |

| Iron | 103% 13.44 mg |

| Magnesium | 50% 179 mg |

| Manganese | 177% 3.721 mg |

| Phosphorus | 64% 451 mg |

| Potassium | 21% 977 mg |

| Sodium | 3% 38 mg |

| Zinc | 47% 4.48 mg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

The entire winged bean plant is edible. The leaves, flowers, roots, and bean pods can be eaten raw or cooked; the pods are edible even when raw and unripe. The seeds are edible after cooking. Each of these parts contains vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, and iron, among other nutrients. The tender pods, which are the most widely eaten part of the plant, are best when eaten before they exceed 2.5 cm (1.0 in) in length. They are ready for harvest within three months of planting. The flowers are used to colour rice and pastry. The young leaves can be picked and prepared as a leaf vegetable, similar to spinach. The nutrient-rich, tuberous roots have a nutty flavour. They are about 20% protein; winged bean roots have more protein than many other root vegetables.[4] The leaves and flowers are also high in protein (10–15%).[4]

The seeds are about 35% protein and 18% fat. They require cooking for two to three hours to destroy the trypsin inhibitors and hemagglutinins that inhibit digestion.[4] They can be eaten dried or roasted. Dried and ground seeds make a useful flour, and can be brewed to make a coffee-like drink.

Winged bean pods

Winged bean pods- A young Burmese woman sells winged bean roots at a market in Mandalay

Boiled winged bean roots served as a snack in Burma

Boiled winged bean roots served as a snack in Burma- Ginataang sigarilyas, a Filipino dish of winged bean (sigarilyas) in coconut milk

The beans are rich not only in protein, but in tocopherols (antioxidants that facilitate vitamin A utilisation in the body).[5] They can be made into milk when blended with water and an emulsifier.[6] Winged bean milk is similar to soy milk, but without the bean-rich flavour.[6] The flavour of raw beans is not unlike that of asparagus.

Smoked pods, dried seeds, tubers (cooked and uncooked), and leaves have been sold in domestic markets in South East and South Asia.[2] Mature seeds can command a high price.[3]

As animal feed

Winged bean is a potential food source for ruminants, poultry,[2] fish, and other livestock.

For commercial fish feed, winged bean is a potentially lower-cost protein source. In Africa, fish meal is especially scarce and expensive.[7] The African sharptooth catfish, a highly valued food fish in Africa,[7] can eat winged bean. In Papua New Guinea highlands region where winged beans thrive, the husks are fed to the domesticated pigs as a dietary supplement.

Germination

Winged bean is a self-pollinating plant but mutations and occasional outcrossing, may produce variations in the species.[2] The pretreatment of winged bean seeds is not required in tropical climate, but scarification of seeds has shown to enhance the germination rate of seedlings.[2] Seed soaking may also increase speed to germination, as is typical, and may be used in conjunction with scarification. Seedlings under natural field conditions have been reported to emerge between five and seven days.[2]

Winged bean can grow at least as fast as comparable legumes, including soy. Plants flower 40 to 140 days after sowing.[2] Pods reach full-length about two weeks after pollination. Three weeks after pollination, the pod becomes fibrous; after six weeks, mature seeds are ready for harvest.[3] Tuber development and flower production vary according to genotype and environmental factors. Some winged bean varieties do not produce tuberous roots.[2] The winged bean is a tropical plant, and will only flower when the day length is shorter than 12 hours, although some varieties have been reported to be day-length neutral.[2][8] All varieties of winged bean grow on a vine and must grow over a support. Some examples of support systems include: growing against exterior walls of houses, huts, buildings; supporting against larger perennial trees; stakes placed in the ground vertically; and structures made from posts and wires.[2]

Because the early growth of winged bean is slow, it is important to maintain weeds. Slow early growth makes winged bean susceptible to weed competition in the first four to six weeks of development.[2] Khan (1982) recommends weeding by hand or animal drawn tractor two times before the support system of the winged bean is established.[2]

Winged bean can be grown without added fertiliser as the plant has a bacterium on the nodules of the roots that fixes nitrogen and allows the plant to absorb nitrogen.[3] Factors that influence nitrogen fixation include, Rhizobium strain, interactions between strain and host genotype, available nutrients and soil pH.[2]

Growing conditions

Although winged bean thrives in hot weather and favours humidity, it is adaptable.[2] The plant's ability to grow in heavy rainfall makes it a candidate for the people of the African tropics.[9]

Winged bean production is optimal in humidity, but the species is susceptible to moisture stress and waterlogging.[2] Ideal growing temperature is 25 °C.[2] Lower temperatures suppress germination, and extremely high temperatures inhibit yield.[2]

Even moderate variations in the growing climate can affect yield. Growing winged bean in lower temperatures can increase tuber production.[2] Leaf expansion rate is higher in a warmer climate. For the highest yields, the soil should remain moist throughout the plant's life cycle.[2] Although the plant is tropical, it can flourish in a dry climate if irrigated.[3] If the plant matures during the drier part of the growing season, yields are higher.[2]

Winged bean is an effective cover crop; planting it uniform with the ground suppresses weed growth.[2] As a restorative crop, winged bean can improve nutrient-poor soil with nitrogen when it is turned over into the soil.[2]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Psophocarpus tetragonolobus. |

- Green bean

- Water spinach

- Yardlong bean

Notes

- Hymowitz, T; Boyd, J. (1977). "Ethnobotany and Agriculture Potential of the Winged Bean". Economic Botany. 31 (2): 180–188. doi:10.1007/bf02866589.

- Khan, T. (1982). Winged Bean Production in the Tropics. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. p. 1.

- National Research Council (U.S.). (1975). Underexploited Tropical Plants with Promising Economic Value. 2nd Edition. U.S. National Academies.

- National Research Council. The winged bean : a high-protein crop for the tropics : report of an ad hoc panel of the Advisory Committee on Technology Innovation. Board on Science and Technology for International Development, 1981

- National Research Council (U.S.), 1975

- Yang, J., Tan, H. (May 2011). Winged Bean Milk. International Conference on New Technology of Agricultural Engineering, Zibo. pp. 814–817. doi:10.1109/ICAE.2011.5943916. ISBN 978-1-4244-9574-0.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Fagbenro, A. (1999). Comparative evaluation of heat-processed Winged bean Psophocarpus tetragonolobus meals as partial replacement for fish meal in diets for the African catfish Clarias gariepinus. Aquaculture 170 (1999), 297-305.

- http://www.echobooks.org/ProductDetails.asp?ProductCode=s407

- Village Earth. (2011). Appropriate Technology: Sustainable Agriculture. Appropriate Technology Library. Chapter: Tropical Legumes. Retrieved from http://villageearth.org/pages/sourcebook/sustainable-agriculture

References

- Venketeswaran, S., M.A.D.L. Dias, and U.V. Weyers. The winged bean: A potential protein crop. p. 445. In: J. Janick and J.E. Simon (eds.), Advances in new crops. Timber Press, Portland, OR (1990).

- Entry for the Winged Bean in the "Leaf for Life" website

- Verdcourt, B.; Halliday, P. (1978). "A revision of Psophocarpus (Leguminosae-Papilionoideae-Phaseoleae)". Kew Bulletin. 33 (2): 191–227. doi:10.2307/4109575. JSTOR 4109575.

- Kadam, S.S.; Lawande, K.M.; Naikare, S.M.; Salunkhe, D.K. (1981). "Nutritional aspects of winged bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus L.DC)". Legume Research. 4 (1): 33–42.

- Smartt, J (1984). "Gene pools in grain legumes". Economic Botany. 38 (1): 24–35. doi:10.1007/bf02904413.

- Hettiarachchy, N.S. and Sri Kantha, S. Nutritive value of winged bean, Psophocarpus tetragonolobus. Nutrisyon (Philippines), 1982; 7: 40–51.

- Sri Kantha, S. and Erdman, J.W.Jr. Winged bean as an oil and protein source; a review. Journal of American Oil Chemists Society, 1984; 61: 215–225.

- Sri Kantha, S. and Erdman, J.W.Jr. Is winged bean really a flop? Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 1986; 18: 339–341.

- National Research Council (U.S). (1975). Underexploited Tropical Plants with Promising Economic Value. 2nd Edition. U.S. National Academies.

- G. J. H. Grubben. (2004). Vegetables: Volume 2 of Plant Resources of Tropical Africa. PROTA

- Village Earth. (2011). Appropriate Technology: Sustainable Agriculture. Appropriate Technology Library. Chapter: Tropical Legumes

- Yang, J., Tan, H. (2011). Winged Bean Milk. International Conference on New Technology of Agricultural, May 2011, 814–817.

- Khan, T. Winged Bean Production in the Tropics. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 1982

- Hymowitz, T.; Boyd, J. (1977). "Origin, Ethnobotany and Agriculture Potential of the Winged Bean - Psophocarpus tetragonolobus". Economic Botany. 31 (2): 180–188. doi:10.1007/bf02866589.

- National Research Council. The winged bean : a high-protein crop for the tropics : report of an ad hoc panel of the Advisory Committee on Technology Innovation. Board on Science and Technology for International Development, 1981

- Fagbenro, A. (1999). Comparative evaluation of heat-processed Winged bean Psophocarpus tetragonolobus meals as partial replacement for fish meal in diets for the African catfish Clarias gariepinus. Aquaculture 170 (1999), 297–305.