Bernard Germain de Lacépède

Bernard-Germain-Étienne de La Ville-sur-Illon, comte de Lacépède or La Cépède (French: [bɛʁnaʁ ʒɛʁmɛn‿etjɛn də la vil syʁ‿ilɔ̃ də la lasepɛd]; 26 December 1756 – 6 October 1825) was a French naturalist and an active freemason. He is known for his contribution to the Comte de Buffon's great work, the Histoire Naturelle.

Bernard Germain de Lacépède | |

|---|---|

Bernard Germain de Lacépède (portrait by Jean-Baptiste Paulin Guérin, 1842) | |

| Born | December 26, 1756 |

| Died | October 6, 1825 (aged 68) |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Continuing Buffon's Histoire Naturelle |

| Awards | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Natural history |

| Institutions | National Museum of Natural History, France |

Biography

_Comte_de_Lac%C3%A9p%C3%A8de.svg.png)

Lacépède was born at Agen in Guienne. His education was carefully conducted by his father, and the early perusal of Buffon's Natural History (Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière) awakened his interest in that branch of study, which absorbed his chief attention. His leisure he devoted to music, in which, besides becoming a good performer on the piano and organ, he acquired considerable mastery of composition, two of his operas (which were never published) meeting with the high approval of Gluck; in 1781–1785 he also brought out in two volumes his Poétique de la musique.

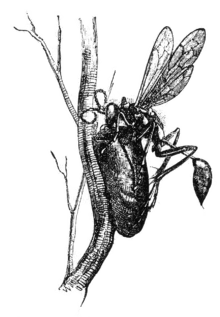

Meantime he wrote two treatises, Essai sur l'électricité (1781) and Physique générale et particulière (1782–1784), which gained him the friendship of Buffon, who in 1785 appointed him subdemonstrator in the Jardin du Roi, and proposed that he continue Buffon's Histoire naturelle. This continuation was published under the titles Histoire naturelle des quadrupèdes ovipares et des serpents. Tome premier (1788) and Histoire naturelle des serpents. Tome second (1789).[1]

After the French Revolution Lacépède became a member of the Legislative Assembly, but during the Reign of Terror he left Paris, his life having become endangered by his disapproval of the massacres. When the Jardin du Roi was reorganised as the Jardin des Plantes and as the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in 1793, Lacépède was appointed to the chair allocated to the study of reptiles and fishes. In 1798, he published the first volume of Histoire naturelle des poissons, the fifth volume appearing in 1803, and in 1804 appeared his Histoire des cétacées. From this period until his death the part he took in politics prevented him making any further contribution of importance to science. In 1799, he became a senator, in 1801 president of the senate (a role he also fulfilled in 1807–08 and 1811–13), in 1803 grand chancellor of the Legion of Honor, in 1804 minister of state, and at the Bourbon Restoration in 1819 he was created a peer of France.

He died at Épinay-sur-Seine. During the latter part of his life he wrote Histoire générale physique et civile de l'Europe, published posthumously in 18 volumes, 1826.[1]

He was elected perpetual secretary of the French Academy of Sciences at the Institute of France in 1796, a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1806 and a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1812.

Lacépède was initiated into freemasonry at 22 years old at Les Neuf Sœurs lodge in Paris, by Jérôme Lalande the worshipfull master himself, who wanted a naturalist for his prestigious lodge. In 1785, Lacépède created his own lodge : "Les Frères Initiés". After the Revolution, he helped Cambacérès to rebuild a French freemasonry submitted to the Emperor, and joined "Saint-Napoléon" lodge where General Kellermann was worshipfull master. He finished his masonic life as dignitary of the Suprême Conseil de France.[2][3][4]

Evolution

Lacépède was an early evolutionary thinker. He argued for the transmutation of species. He believed that species change over time and may go extinct from geological cataclysms or become "metamorphosed" into new species.[5] In his book Histoire naturelle des poissons, he wrote:

"The species can undergo such a large number of modifications in its forms and qualities, that without losing its vital capacity, it may be, by its latest conformation and properties, farther removed from its original state than from a different species: it is in that case metamorphosed into a new species."[6]

Hommages

- Lacepede Bay in South Australia, and the Lacepede Islands off the northern coast of Western Australia,[7] are named after him.The street Lacepede in Paris.

- The street Rue Lacepede near the Jardin des Plantes and the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris was named after him.

Works

- Les ages de la nature et histoire de l'espèce humaine. Paris 1830 p.m.

- Histoire naturelle de l'homme. Pitois-Le Vrault, Paris 1827 p.m.

- Histoire générale, physique et civile de l'Europe. Cellot, Mame, Delaunay-Vallée & de Mat, Paris, Brüssel 1826 p.m.

- Histoire naturelle des quadrupèdes ovipares, serpents, poissons et cétacées. Eymery, Paris 1825.

- Histoire naturelle des cétacées. Plassan, Paris 1804.

- Notice historique sur la vie et les ouvrages de Dolomieu. Bossange, Paris 1802.

- La menagerie du Museum national d'histoire naturelle. Miger, Paris 1801–04.

- Discours d'ouverture et de clôture du cours de zoologie. Plassan, Paris 1801.

- Discours d'ouverture et de clôture du cours d'histoire naturelle. Plassan, Paris 1799.

- Lacépède, Bernard Germain (1798–1803). Illustrations de Histoire naturelle des poissons. Marie-Anne Rousselet (engraver). Paris, France: Chez Passan.

- Discours d'ouverture et de clôture du cours d'histoire naturelle des animaux vertébrés et a sang rouge. Plassan, Paris 1798.

- Discours d'ouverture du Cours d'histoire naturelle. Paris 1797.

- Histoire naturelle des serpents. Tome second. de Thou, Paris 1789.

- Histoire naturelle des quadrupèdes ovipares et des serpens. Tome premier.. de Thou, Paris 1788.

- Vie de Buffon. Maradan, Amsterdam 1788.

- La poétique de la musique. Paris 1785.

- Physique générale et particulière. Paris 1782–84.

- Essai sur l'électricité naturelle et artificielle. Paris 1781.

References

-

- Dictionnaire universelle de la Franc-Maçonnerie (Marc de Jode, Monique Cara and Jean-Marc Cara, ed. Larousse , 2011)

- Dictionnaire de la Franc-Maçonnerie (Daniel Ligou, Presses Universitaires de France, 2006)

- Lacépède: Savant, musicien, philanthrope et musicien (Bernard Quilliet, ed. Tallandier, 2013)

- Richards, Robert J. (1987). Darwin and the Emergence of Evolutionary Theories of Mind and Behavior. University of Chicago Press. pp. 57-58. ISBN 0-226-71200-1

- "Bernard-Germain-Etienne Lacépède (1756-1825)" Archived 7 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine. National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 March 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Lacépède", p. 149).

Further reading

- Schmitt, Stéphane (2010). "Lacepède’s syncretic contribution to the debates on natural history in France around 1800". Journal of the History of Biology 43: 429-457.

- Cuvier, Georges (1876). Éloges historiques de MM. de Saussure, Pallas, Hauy, de Lacépède et Cavendish. Münster: Theissing. (in French).

- Saloman, Ora Frishberg (1984). Aspects of "Gluckian" operatic thought and practice in France. Ann Arbor.

- Roule, Louis (1932). Lacépède, professeur au Muséum, premier grand chancellier de la Légion d'honneur, et la sociologie humanitaire selon la nature. Paris: Flammarion. (in French).

External links

- Internet Archive Works by Lacepede

- Lacépède (1856) Histoire naturelle de Lacépède, 2 vol. – Linda Hall Library