Battle of Trevilian Station

The Battle of Trevilian Station (also called Trevilians) was fought on June 11–12, 1864, in Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Overland Campaign against Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Union cavalry under Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan fought against Confederate cavalry under Maj. Gens. Wade Hampton and Fitzhugh Lee in the bloodiest and largest all-cavalry battle of the war.

Sheridan's objectives for his raid were to destroy stretches of the Virginia Central Railroad, provide a diversion that would occupy Confederate cavalry from understanding Grant's planned crossing of the James River, and to link up with the army of Maj. Gen. David Hunter at Charlottesville. Hampton's cavalry beat Sheridan to the railroad at Trevilian Station and on June 11 they fought to a standstill. Brig. Gen. George A. Custer entered the Confederate rear area and captured Hampton's supply train, but soon became surrounded and fought desperately to avoid destruction.

On June 12, the cavalry forces clashed again to the northwest of Trevilian Station, and seven assaults by Brig. Gen. Alfred T. A. Torbert's Union division were repulsed with heavy losses. Sheridan withdrew his force to rejoin Grant's army. The battle was a tactical victory for the Confederates and Sheridan failed to achieve his goal of permanently destroying the Virginia Central Railroad or of linking up with Hunter. Its distraction, however, may have contributed to Grant's successful crossing of the James River.

Background

Following the bloody Union repulse at the Battle of Cold Harbor on June 3, Grant decided on a new strategy. Since May 4, his Overland Campaign had consisted of major battles against Robert E. Lee, each of which (the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, North Anna, Totopotomoy Creek, and Cold Harbor) was followed by a period of stalemate and then a maneuver around Lee's right flank in an attempt to draw him away from his entrenchments and into the open. Each maneuver brought the armies closer to the Confederate capital of Richmond, but the city was not the main objective—the destruction of Lee's army was the goal established by Grant and President Abraham Lincoln, with the understanding that Richmond and the Confederacy would fall if Lee were defeated.[5]

Grant's new strategy was to march his 100,000-man army to the south, cross the James River, and seize the rail hub of Petersburg. This would cut off the supply lines to both Richmond and Lee, forcing the evacuation of the capital, and probably inducing Lee to attack Grant's army in a manner favorable to Grant's superior numbers and firepower. His plan required secrecy because his army would be vulnerable if intercepted while crossing the river and he sought to reach Petersburg before the city's defenses could be enhanced beyond the token force that was currently there. Therefore, on June 5 Grant ordered a cavalry raid by the command of Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan northwest toward Charlottesville. The raid had two initial objectives. First, Sheridan would draw the Confederate cavalry away from Grant's main army so his infantry corps could stealthily disengage from Lee's army at Cold Harbor and move toward the James. Second, the Union cavalrymen would tear up the Virginia Central towards Richmond, cutting off Lee's army from the much needed food supplies produced by the Shenandoah Valley. Sheridan was ordered to destroy the railroad bridge on the Rivanna River, just east of Charlottesville, and destroy the tracks from there to Gordonsville. Then, his men would turn back and destroy the track all the way to Hanover Junction, near Richmond.[6]

Just after Grant issued the orders to Sheridan he learned of Maj. Gen. David Hunter's Union victory at the Battle of Piedmont in the Shenandoah Valley against Brig. Gen. William E. "Grumble" Jones. He saw the opportunity that Hunter could travel east from Staunton to meet Sheridan at Charlottesville so that they could be a combined threat to Lee's army from the west. Grant modified his orders, telling Sheridan to wait for Hunter near Charlottesville, and then detach a brigade to cut the James River Canal.[7]

Opposing forces

Union

| Key Union commanders |

|---|

|

The Cavalry Corps of the Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, began its raid with two of its three divisions, 9,286 men,[2] organized as follows:[8]

- First Cavalry Division, commanded by Brig. Gen. Alfred T. A. Torbert, consisted of the brigades commanded by Brig. Gens. George A. Custer and Wesley Merritt, and Col. Thomas C. Devin.

- Second Cavalry Division, commanded by Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg, consisted of the brigades commanded by Brig. Gen. Henry E. Davies, Jr., and Col. J. Irvin Gregg (General Gregg's cousin).

- Horse Artillery Brigade, commanded by Capt. James M. Robertson, included six artillery batteries with 20 guns.

Sheridan's Third Cavalry Division, commanded by Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson, remained at Cold Harbor with the Army of the Potomac, under the supervision of army commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. It accompanied the army on its march to Petersburg. Sheridan left behind with Wilson the men from his other two divisions who did not have mounts.[9]

Confederate

| Key Confederate commanders |

|---|

|

The Cavalry Corps of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia was without a formal commander, following the death of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart in May. The senior cavalry commander opposing Sheridan's force was Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton. (Hampton was named the formal commander of the Cavalry Corps on August 11, 1864.) Hampton's command consisted of 6,762 men,[2] organized as follows:[10]

- Hampton's Division, commanded by Wade Hampton, consisted of the brigades commanded by Brig. Gens. Thomas L. Rosser and Matthew C. Butler, and Col. Gilbert J. Wright. (Rosser's brigade was also known as the Laurel Brigade. Wright commanded Young's Brigade, named for its former commander, Brig. Gen. M. B. Young.) Butlers Brigade also included Cadet Rangers from the South Carolina Military Academy, (now The Citadel), who were part of the 4th Regiment South Carolina Cavalry.[11][12]

- Fitzhugh Lee's Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee (General Robert E. Lee's nephew), consisted of the brigades of Brig. Gens. Williams C. Wickham and Lunsford L. Lomax, and an independent command with the 1st Maryland Cavalry Battalion, commanded by Col. Bradley T. Johnson, and the Baltimore Light Artillery.

- Horse Artillery Battalion, commanded by Maj. James Breathed, included four artillery batteries. Hampton's overall artillery strength was 14 guns.

The rest of the Cavalry Corps—Rooney Lee's Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. W.H.F. "Rooney" Lee (Robert E. Lee's son), an independent cavalry command under Brig. Gen. Martin Gary, and the bulk of the horse artillery—remained with the army during Sheridan's raid.[10]

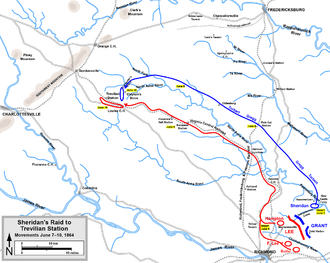

Start of Sheridan's raid

Sheridan and his two cavalry divisions left their camps north of Cold Harbor at 5 a.m. on June 7. They crossed a pontoon bridge at New Castle over the Pamunkey River and headed northwest, with Gregg's division in the lead, Torbert's following. The weather was hot and enormous clouds of dust billowed over the march. On the first day, the column was able to march only about 15 miles. Numerous horses collapsed under the strain, and following the convention Sheridan used in his May raid to Yellow Tavern and Richmond, they were shot and left at the side of the road. Although there were 125 wagons following Sheridan's column, the men were issued only three days' rations and were expected to feed themselves and their horses along the way; dismounted foraging parties spread out along the route. On the second day, with Torbert's division in the lead, the Federals made better progress, covering the 25 miles to Pole Cat Station on the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad. The Union column was plagued not only by the heat and humidity of the Virginia summer; skirmishing with irregular mounted raiding parties delayed the advance.[13]

Confederate scouts passed word of Sheridan's movements to Hampton on the morning of June 8. He correctly guessed that the Union targets were the railroad junctions at Gordonsville and Charlottesville, and knew that he would have to move quickly to block the threat. He ordered his own division to assemble at 2 a.m. on June 9 and directed Fitzhugh Lee to follow them as rapidly as possible. Although the Federals had a two-day head start, the Confederates had the advantage of a shorter route (about 45 miles versus 65) and terrain that was more familiar to them. On June 9, the first anniversary of the Battle of Brandy Station, they walked at a slow, deliberate pace, covering nearly 30 miles through Yellow Tavern, up the Telegraph Road, and then following the route of the Virginia Central Railroad to Bumpass and Fredericks Hall Stations.[14]

By the evening of June 10, both forces had converged around Trevilian Station, named for Charles Goodall Trevilian, who owned a plantation house near the station. The Confederates camped in four locations immediately south of the Virginia Central on the Gordonsville Road, from just west of Trevilian Station east to Louisa Court House. The Federals had crossed over the North Anna River at Carpenters Ford and camped at locations around Clayton's Store.[15]

Battle

June 11, 1864

At dawn on June 11, Hampton was awakened by Rosser and Butler to the sound of bugles stirring the enemy. The two Confederate brigade commanders had already roused their men. Rosser asked, "General, what do you propose to do today, if I may inquire?" Hampton replied, "I propose to fight!"[16]

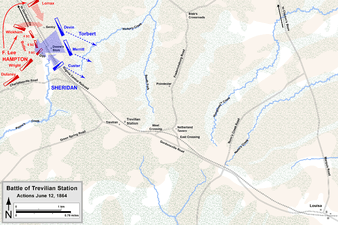

Hampton was told by Black Union orderly, spying for General Rosser in Union HQs,[17] that Sheridan's force would approach the railroad from the direction of Clayton's Store and he knew that there were two roads leading south from that crossroads location, both through thick woods. One road led to Trevilian Station and the other to Louisa Court House. Hampton devised a plan in which he would split his divisions across the roads and converge on the enemy at the crossroads, pushing Sheridan back to the North Anna River. Hampton took two of his brigades (Butler's and Wright's) with him from Trevilian with his third (Rosser's) remaining on his left to prevent flanking. The other division under Fitzhugh Lee was ordered to advance from Louisa Court House, making up the right flank.[18]

While the Confederates began their advance, Sheridan started his. Torbert's brigades under Merritt and Devin moved down the road to Trevilian Station while his third, Custer's, advanced toward Louisa Court House. The first contact occurred on the Trevilian Road as the 4th South Carolina Cavalry of Butler's Brigade clashed with Merritt's skirmish line. Hampton dismounted his men and pushed the skirmishers back into the thick woods, expecting Fitzhugh Lee to arrive on his right at any minute. However, Hampton was severely outnumbered and soon he was forced back. Eventually Wright's Brigade joined in the close-quarter fighting in the thick brush, but after several hours they also were pushed back within sight of Trevilian Station. Some of Hampton's staff officers grumbled that Fitz Lee had not come to Hampton's aid as expected because of his unwillingness to support any superior officer other than J.E.B. Stuart.[19]

On the right flank, Fitzhugh Lee encountered the advancing brigade under Custer. Wickham's Brigade fought briefly with the 1st and 7th Michigan Cavalry and then withdrew. Lee led Lomax's Brigade directly toward Trevilian Station and Wickham came up through Louisa Court House on their rear. Meanwhile, Custer led his brigade on a more direct road southwest to Trevilian Station. Custer found the station totally unguarded, occupied only by Hampton's trains—supply wagons, caissons containing ammunition and food, and hundreds of horses. He ordered the 5th Michigan Cavalry to charge and capture the lot, which they did with enthusiasm. The Michiganders captured 800 prisoners, 90 wagons, six artillery caissons, and 1,500 horses, but left Custer cut off from Sheridan, and in their pursuit of the fleeing wagons, lost a number of their own men and much of their bounty. One of Wright's regiments, the 7th Georgia, got between Custer's force and Trevilian Station. Custer ordered the 7th Michigan to charge, driving the Georgians back.[20]

Hampton now learned of the threat in his rear area and withdrew Rosser's Brigade from protecting his left flank and sent them to the station, converging with Lee's approach from Louisa Court House and with Wright's and Butler's brigades. Suddenly Custer found his luck had run out as he was pressured from three sides at the station. He pulled out and headed along the Gordonsville Road, taking his burdensome spoils with him. However, he failed to note a Confederate horse artillery battery on a hill north of the station, which opened fire as soon as his men were in range. At this point his right flank was further overwhelmed by Hampton's charging brigades.[21]

Custer was now virtually surrounded, his command in an ever-shrinking circle, as every side was charged and hit with shells. Historian Eric J. Wittenberg described the general's predicament as "Custer's First Last Stand", foreshadowing his famous demise at the Battle of Little Bighorn. Custer, suspecting that his command would soon be overrun and concerned that his flag would be captured, tore it from its staff when the flag-bearer was hit and hid it within his coat. Sheridan at this point heard the firing from Custer's direction and realized he needed help. He charged with Devin's and Merritt's brigades, pushing Hampton's men back all the way to the station, while Gregg's brigade was ordered to swing into Fitzhugh Lee's exposed right flank, thus pushing him back. Hampton fell back to the west, Lee to the east, and the battle ended for the day with the Federals in possession of Trevilian Station. Custer's brigade had suffered 361 casualties, including more than one half of the 5th Michigan. When Sheridan asked Custer if he had lost his colors, he pulled them from his coat and exclaimed, "Not by a damned sight!"[22]

That night, Fitzhugh Lee maneuvered south to link up with Hampton to the west of Trevilian Station. Sheridan learned that General Hunter was not headed for Charlottesville as originally planned, but to Lynchburg. He also received intelligence that Confederate Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge's infantry had been sighted near Waynesboro, effectively blocking any chance for further advance, so he decided to abandon his raid and return to the main army at Cold Harbor.[23]

June 12, 1864

On June 12, as the Union cavalry prepared to withdraw, Gregg's division destroyed Trevilian Station, several railcars, and about a mile of track to the east of the station, while Torbert's division tore up track to the west. Concerned about the Confederates hovering near his flank, at about 3 p.m. Sheridan sent Torbert's three brigades, supported by Davies's brigade of Gregg's division, on a reconnaissance west on the Gordonsville and Charlottesville roads. They found Hampton's entire force in an L-shaped line behind some log breastworks at the Ogg and Gentry farms, two miles northwest of Trevilian.[24]

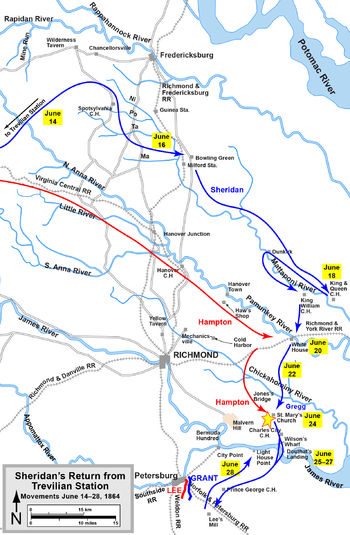

Torbert launched seven assaults against the apex and shorter leg of the "L", but his brigades were repulsed with heavy losses. Fitzhugh Lee detached his division from the line and his brigades under Wickham and Lomax swung around to hit the Union right flank with a strong counterattack. The battle ended about 10 p.m., with both sides remaining in place. Late in the night, however, Torbert withdrew. Sheridan, burdened with many wounded men, disproportionately from Custer's brigade, about 500 prisoners, and a shortage of ammunition, decided to withdraw. He planned a leisurely march back to Cold Harbor, knowing that Hampton would be obliged to follow and would be kept occupied for days, unavailable in that time to Robert E. Lee.[25]

Aftermath

The results of the Battle of Trevilian Station were mixed. Union casualties were 1,007 (102 killed, 470 wounded, and 435 missing or captured). Confederate losses were reported as 612, but this includes the losses from only Hampton's Division and 831 is a better total estimate.[4] It was the bloodiest and largest all-cavalry engagement during the war.[26]

Sheridan maintained that the battle was a Union victory. In 1866, he wrote, "The result was constant success and the almost total annihilation of the rebel cavalry. We marched when and where we pleased; were always the attacking party, and always successful." Ulysses S. Grant's personal memoirs agreed with the sentiment and many of Sheridan's biographers accept his claim. As a diversion, it can be considered a partial success for the Union; it was not until Grant began attacking the weak forces at Petersburg that General Lee finally understood that the Union Army had maneuvered away from him and crossed the James River. However, Sheridan failed in two important objectives. He was unable to permanently disrupt the Virginia Central Railroad because within two weeks the track was repaired and supplies continued to flow to General Lee's army. The planned rendezvous between Sheridan and Hunter failed completely. Hunter was subsequently defeated at the Battle of Lynchburg (June 17–18) by Lt. Gen. Jubal Early in the Valley and was soon pushed back far into Maryland. Eric J. Wittenberg, the author of the modern definitive study of the battle, asserts that if Sheridan had successfully destroyed the railroad, Hunter might have succeeded in capturing Lynchburg because Early would have been forced to deal with Sheridan instead. He called the battle an "unmitigated disaster" for the Federal cavalry and stated that "nothing about the Battle of Trevilian Station can be considered to be a Union victory."[27]

It was for his actions at the Battle of Trevilian Station that noted architect Frank Furness was awarded the Medal of Honor.[28]

Battlefield preservation

The Civil War Trust (a division of the American Battlefield Trust) and its partners have acquired and preserved 2,226 acres (9.01 km2) of the battlefield in more than a dozen transactions since 2001. Much of this land is now owned by the Trevilian Station Battlefield Foundation, which has developed an online driving tour that begins at the Louisa County Courthouse.[29]

See also

Notes

- NPS Archived April 9, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Starr, p. 149, states that the fighting on June 11 "despite Confederate claims to the contrary, was without question a Federal success", but that the fighting on June 12 was not and the campaign as a whole was "undoubtedly a failure."

- Wittenberg, pp. 342, 345. Salmon, p. 298, cites 6,000 Union, 4,700 Confederate. Kennedy, p. 294, cites 5,000 Confederates. Davis, pp. 21-22, cites 8,000 Union, 4,700 Confederate. Longacre, p. 299, cites "more than 9,000" Union, 6,500 Confederate. Starr, pp. 129, 136, cites 6,000 Union, 4,700 Confederate; Starr explains that the 6,000 number was based on Sheridan leaving behind with Wilson all of his men who lacked mounts.

- General summary from the Rapidan to the James River, May 5-June 24, 1864: Official Records, Series I, Volume XXXVI, Part 1, page 188.

- 1,007 total (95 killed; 445 wounded; 410 missing/captured) according to Wittenberg, pp. 342, 345; Wittenberg cites specific casualties for Hampton's Division (59 killed, 258 wounded, 295 missing/captured), plus 161 total casualties for Lee's Division, and 30 for the horse artillery. Eicher, p. 694, cites 1,007 Union (102 killed, 470 wounded, 435 missing/captured) and 612 Confederate (which accounts only for Hampton's Division). Urwin, p. 1975, reports 735 Union casualties, including 416 in Custer's brigade. Salmon cites more than 1,000 on each side. Kennedy, p. 295, cites 1,007 Union, 1,071 Confederate. NPS Archived April 9, 2005, at the Wayback Machine cites 1,600 total (both sides).

- Salmon, p. 252-58.

- Starr, p. 127; Salmon, p. 298; Davis, pp. 18-19; Welcher, p. 1052.

- Davis, p. 20; Starr, p. 129; Salmon, pp. 341-42.

- Welcher, p. 1054; Wittenberg, pp. 331-33.

- Welcher, p. 1054; Wittenberg, pp. 335; Starr, p. 129.

- Wittenberg, pp. 333-35; Longacre, p. 299; Davis, p. 21.

- "War Between The States". The Citadel. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- "The Citadel Cadets". Civil War Talk Forums. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- Wittenberg, pp. 37-42; Davis, p. 21; Welcher, p. 1052; Starr, p. 133.

- Wittenberg, pp. 42-47; Welcher, p. 1052; Starr, pp. 134-36; Davis, p. 21.

- Wittenberg, pp. 50-56, 170; Salmon, p. 298.

- Davis, p. 22. Wittenberg, p. 71, does not use the exclamation point in the quotation, and remarks that Hampton said it "nonchalantly."

- Conrad "Rebel Scout" pg 107-8, Rosser "Riding with Rosser" pg 37

- Longacre, pp. 299-300; Starr, pp. 136-37; Davis, p. 22.

- Wittenberg, pp. 76-87; Starr, p. 138; Longacre, p. 300; Welcher, p. 1052.

- Wittenberg, pp. 97-102; Starr, p. 137; Davis, pp. 23-24.

- Longacre, p. 300; Davis, p. 24; Wittenberg, pp. 105-117; Starr, p. 139; Welcher, p. 1052.

- Wittenberg, pp. 124-25; Starr, pp. 140-41; Welcher, pp. 1052-53; Davis, pp. 24-25; Longacre, pp. 301-302.

- Wittenberg, pp. 157, 172; Welcher, p. 1053; Starr, p. 142; Salmon, p. 299. Kennedy, p. 295, states that Lee joined Hampton at noon on June 12.

- Wittenberg, pp. 183-98; Welcher, p. 1053; Davis, p. 25; Longacre, p. 303.

- Kennedy, p. 295; Wittenberg, pp. 198-209; Longacre, p. 303; Davis, p. 25; Welcher, p. 1053, cites 370 prisoners, 400 wounded, and 2,000 "Negroes".

- Salmon, p. 300. Historians sometimes claim that the 1863 Battle of Brandy Station was the largest, but of the 20,500 men engaged there, 3,000 were infantry, so it can be categorized as the largest predominantly cavalry battle. Although the casualties of the two battles were similar in absolute numbers, Trevilian Station represented higher percentages of casualties on both sides.

- Wittenberg, pp. 301-305.

- "Frank Furness". Rushlancers. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- "Trevilian Station". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

References

- Davis, William C., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. Death in the Trenches: Grant at Petersburg. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1986. ISBN 0-8094-4776-2.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Longacre, Edward G. Lee's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of Northern Virginia. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002. ISBN 0-8117-0898-5.

- Salmon, John S. The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

- Starr, Stephen Z. The Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Vol. 2, The War in the East from Gettysburg to Appomattox 1863–1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0-8071-3292-0.

- Urwin, Gregory J. W. "Battle of Trevilian Station." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Welcher, Frank J. The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations. Vol. 1, The Eastern Theater. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-253-36453-1.

- Wittenberg, Eric J. (2007). Glory Enough for All: Sheridan's Second Raid and the Battle of Trevilian Station. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-5967-6.

- National Park Service battle description

- CWSAC Report Update

Further reading

- Butler, M. C. "The Cavalry Fight at Trevilian Station." In Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. 4, edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence C. Buel. New York: Century Co., 1884-1888. OCLC 2048818.

- Longacre, Edward G. Lincoln's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of the Potomac. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2000. ISBN 0-8117-1049-1.

- Morris, Roy, Jr. Sheridan: The Life and Wars of General Phil Sheridan. New York: Crown Publishing, 1992. ISBN 0-517-58070-5.

- Rodenbough, Theodore F. "Sheridan's Trevilian Raid." In Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. 4, edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence C. Buel. New York: Century Co., 1884-1888. OCLC 2048818.

- Sheridan, Philip H. Personal Memoirs of P. H. Sheridan. 2 vols. New York: Charles L. Webster & Co., 1888. ISBN 1-58218-185-3.

- Swank, Walbrook Davis. Battle of Trevilian Station: The Civil War's Greatest and Bloodiest All Cavalry Battle, with Eyewitness Memoirs. Shippensburg, PA: W. D. Swank, 1994, ISBN 0-942597-68-0.

- Wellman, Manly Wade. Giant in Gray: A Biography of Wade Hampton of South Carolina. Dayton, OH: Press of Morningside Bookshop, 1988. ISBN 0-89029-054-7.

- Wittenberg, Eric J. Little Phil: A Reassessment of the Civil War Leadership of Gen. Philip H. Sheridan. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2002. ISBN 1-57488-548-0.

- Baker, Gary R. Cadets in Grey: The Story of the Cadets of the South Carolina Military Academy and the Cadet Rangers in the Civil War. Lexington, SC: Palmetto Bookworks, 1989. ISBN 0-9623065-0-9.

External links

- Trevilian Station Battlefield Foundation

- The Battle of Trevilian Station: Maps, histories, photos, and preservation news (Civil War Trust)