Battle of Hutong (1658)

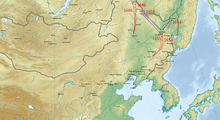

The Battle of Hutong was a military conflict which occurred on 10 June 1658 between the Tsardom of Russia and the Qing dynasty and Joseon. It resulted in Russian defeat.[4]

| Battle of Hutong (1658) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Sino-Russian border conflicts | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Tsardom of Russia |

Qing dynasty Joseon | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Onufriy Stepanov † |

Šarhūda Sin Ryu | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

500 Cossacks[1] 11 ships |

1,340 Manchus[1] 260 Koreans[2] 50 ships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

220 killed[3] 7 ships destroyed 3 ships captured |

Qing: 110 killed, 200 wounded[3] Joseon: 8 killed, 25 wounded[3] | ||||||

Background

In 1657, Šarhūda commissioned the construction of large warships which could stand up to the Russian vessels. By the next year, 52 vessels had been produced, 40 of which were large and mounted with cannons of various sizes.[2]

Sin Ryu's 260 musketeers arrived at Ningguta on 9 May. A day later, the allied forces set sale towards the mouth of the Songhua River. After five days, they ran into a group of Duchers who informed them that the Russians were in the area. They waited there for fifty of Šarhūda's newly built warships to arrive. The war fleet arrived on 2 June and set sail again three days later.[1]

Battle

The allied forces encountered Onufriy Stepanov's fleet on 10 June. The Russians set up a defensive formation along a riverbank, where they exchanged fire with the Qing ships to no great effect. Once the allied forces closed in, the Cossacks broke formation and fled to shore or hid in their ships. Just as the Korean forces were about to set fire to the Russian ships, Šarhūda halted them because he wanted to keep the ships as booty. Taking advantage of the brief lull in battle, the Cossacks counterattacked, killing many of the allied forces. Forty Cossacks managed to board a deserted Qing vessel and flee but they were eventually hunted down and slaughtered. The Russian ships were destroyed using fire arrows.[3]

Aftermath

The Russian defeat cost them control of the lower Amur region up to Nerchinsk, where only 76 Cossacks garrisoned the fortress. Half these men deserted the outpost soon after. Although a group of independent Cossacks would return to Albazin in the 1660s, the Russian state withdrew most of its commitment to the Amur region, leaving it a no man's land.[5]

References

- Kang 2013, p. 167.

- Kang 2013, p. 165.

- Kang 2013, p. 168.

- Narangoa 2014, p. 46.

- Kang 2013, p. 169.

Bibliography

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Kang, Hyeok Hweon (2013), "Big Heads and Buddhist Demons: The Korean Musketry Revolution and the Northern Expeditions of 1654 and 1658" (PDF), Journal of Chinese Military History, 2

- Narangoa, Li (2014), Historical Atlas of Northeast Asia, 1590-2010: Korea, Manchuria, Mongolia, Eastern Siberia, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 9780231160704