Ubaidullah Sindhi

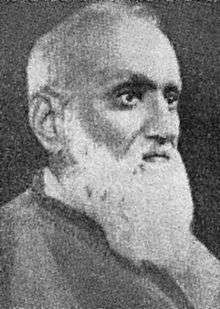

Buta Singh Uppal, later known as Ubaidullah Sindhi (Sindhi: عبیداللہ سنڌي (Nastaleeq), उबैदुल्लाह सिंधी (Devanagari), Punjabi: مولانا عبداللہ (Shahmukhi), ਮੌਲਾਨਾ ਉਬੈਦੁਲਾ (Gurmukhi), Urdu: مولانا عبیداللہ سندھی), (10 March 1872 – 21 August 1944) was a political activist of the Indian independence movement and one of its vigorous leaders. According to Dawn, Karachi, Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi struggled for the independence of British India and for an exploitation-free society in India.[2] He was also Home Minister of first Provisional Government of India established in Afghanistan in 1915.

Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi | |

|---|---|

Moulana Ubaidullah Sindhi | |

| Born | 10 March 1872 Sialkot, Punjab, British India |

| Died | 21 August 1944 (aged 72)[1] Rahim Yar Khan District, Punjab, British India, (now in Pakistan) |

| Occupation | Political activist/Islamic philosopher/scholar |

| Years active | 1909-1944 |

| Era | British Raj |

Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi was the Life Member of Jamia Millia Islamia, A Central University in New Delhi, India. He served the Jamia Millia Islamia for a long period of time on a very low salary. A boys' hostel in Dr. Zakir Husain Hall of Hall of Boys' Residence in Jamia Millia Islamia has been named after him.

Early life and Education

Ubaidullah was born on 10 March 1872[1] in an Uppal Khatri family in the district of Sialkot, Punjab, British India as Buta Singh Uppal. His father died four months before Ubaidullah was born, and the child was raised for two years by his paternal grandfather. Following the paternal grandfather's death, he was taken by his mother to the care of her father, at his maternal grandfather's house. Later, young Buta Singh was entrusted to the care of his uncle at Jampur Tehsil, Punjab, British India, when his maternal grandfather died. Buta Singh Uppal converted to Islam at age 15 and chose "Ubaidullah Sindhi" as his new name, and later enrolled in the Darul Uloom Deoband, where he was, at various times, associated with other noted Islamic scholars of the time, including Maulana Rasheed Gangohi and Maulana Mahmud al-Hasan. Maulana Sindhi returned to the Darul Uloom Deoband in 1909, and gradually involved himself in the Pan-Islamic movement. During World War I, he was among the leaders of the Deoband School, who, led by Maulana Mahmud al-Hasan, left India to seek support among other nations of the world for a Pan-Islamic revolution in India in what came to be known as the Silk Letter Conspiracy.[1]

Ubaidullah had reached Kabul during the war to rally the Afghan Amir Habibullah Khan, and after a brief period there, he offered his support to Raja Mahendra Pratap's plans for revolution in British India with German support. He joined the Provisional Government of India formed in Kabul in December 1915, and remained in Afghanistan until the end of World War I, and then left for Russia. He subsequently spent two years in Turkey and, passing through many countries, eventually reached Hijaz (Saudi Arabia) where he spent about 14 years learning and pondering over the philosophy of Islam especially in the light of Shah Waliullah Dehlawi's works. In his early career he was a Pan-Islamic thinker. However, after his studies of Shah Waliullah's works, Ubaidullah Sindhi emerged as non-Pan-Islamic scholar. He was one of the most active and prominent members of the faction of Indian Freedom Movement led by Muslim clergy chiefly from the Islamic School of Deoband. Ubaidullah Sindhi was a great freedom fighter of India.[1][2]

Conversion to Islam

When he was at school, a Hindu friend gave him the book Tufatul Hind to read. It was written by a converted scholar Maulana Ubaidullah of Malerkotla. After reading this book and some other books like Taqwiyatul Eeman and Ahwaal ul Aakhira, Ubaidullah's interest in Islam grew, leading eventually to his conversion to Islam. In 1887, the year of his conversion, he moved from Punjab to Sindh area where he was taken as a student by Hafiz Muhammad Siddique of Chawinda (Bhar Chandi). He subsequently studied at Deen Pur village under Maulana Ghulam Muhammad where he delved deeper into Islamic education and training in the mystical order. In 1888, Ubaidullah was admitted to Darul Uloom Deoband, where he studied various Islamic disciplines in depth under the tutelage of noted Islamic scholars of the time including Maulana Abu Siraj, Maulana Rasheed Ahmad Gangohi and Maulana Mahmud al Hasan. He took lessons in Sahih al-Bukhari and Tirmidhi from Maulana Nazeer Husain Dehalvi and read logic and philosophy with Maulana Ahmad Hasan Cawnpuri.

In 1891, Ubaidullah graduated from the Deoband school. He left for Sukkur area in Sindh province, and started teaching in Amrote Shareef under, or with, Maulana Taj Mohammad Amrothi, who became his mentor after the death of Hafiz Muhammad Siddique of Bhar Chandi. Ubaidullah married the daughter of Maulana Azeemullah Khan, a teacher at Islamiyah High School, at that time. In 1901, Ubaidullah established the Darul Irshaad in Goth Peer Jhanda village in Sindh. He worked on propagating his school for nearly seven years. In 1909, at the request of Mahmud Al Hasan, he returned to Deoband School in Uttar Pradesh. Here, he accomplished much for the student body, Jamiatul Ansaar. Ubaidullah was now very active in covert anti-British propaganda activities, which led to him alienating a large number of the Deoband School leaders. Subsequently, Ubaidullah moved his work to Delhi at Mahmud al Hasan's request. At Delhi, he worked with Hakim Ajmal Khan and Dr. Ansari. In 1912, he established a madrassah, Nazzaaratul Ma'arif, which was successful in propagating and spreading Islam among the people.

Attempt to involve Afghanistan's ruler

With the onset of World War I in 1914, efforts were made by the Darul Uloom Deoband to forward the cause of Pan-Islam in British India with the help of the other sympathetic nations of the world. Led by Mahmud al Hasan, plans were sketched out for an insurrection beginning in the tribal belt of North-West Frontier Province of British India.[3][4] Mahmud al Hasan, left India to seek the help of Galib Pasha, the Turkish governor of Hijaz, while at Hasan's directions, Ubaidullah proceeded to Kabul to seek Emir Habibullah's support there. Initial plans were to raise an Islamic army (Hizb Allah) headquartered at Medina, with an Indian contingent at Kabul. Maulana Hasan was to be the General-in-chief of this army.[4] Some of Ubaidullah's students went to Kabul to explore things before Ubaidullah arrived there. While at Kabul, Ubaidullah came to the conclusion that focusing on the Indian Freedom Movement would best serve the pan-Islamic cause.[5] Ubaidullah had proposed to the Afghan Emir that he declare war against British India.[6][7] Maulana Abul Kalam Azad is known to have been involved in the movement prior to his arrest in 1916.[3][1]

Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi and Mahmud al Hasan (principal of the Darul Uloom Deoband) had proceeded to Kabul in October 1915 with plans to initiate a Muslim insurrection in the tribal belt of British India. For this purpose, Ubaid Allah was to propose that the Amir of Afghanistan declares war against Britain while Mahmud al Hasan sought German and Turkish help. Hasan proceeded to Hijaz. Ubaidullah, in the meantime, was able to establish friendly relations with Emir Habibullah of Afghanistan. At Kabul, Ubaidullah along with some of his students, were to make their way to Turkey to join the Caliph's "Jihad" against Britain. But it was eventually decided that the pan-Islamic cause was to be best served by focusing on the Indian Freedom Movement.[5]

In late 1915, Sindhi was met in Kabul by the 'Niedermayer-Hentig Expedition' sent by the Indian Independence Committee in Berlin and the German war ministry. Nominally led by the exiled Indian prince Raja Mahendra Pratap, it had among its members the Islamic scholar Abdul Hafiz Mohamed Barakatullah, and the German officers Werner Otto von Hentig and Oskar Niedermayer, as well as a number of other notable individuals. The expedition tried to rally Emir Habibullah's support, and through him, begin a campaign into British India. It was hoped that it would initiate a rebellion in British India. On 1 December 1915, the Provisional Government of India was founded at Emir Habibullah's 'Bagh-e-Babur palace' in the presence of the Indian, German, and Turkish members of the expedition. It was declared a 'revolutionary government-in-exile' which was to take charge of independent India when British authority is overthrown.[8] Mahendra Pratap was proclaimed its President, Barkatullah the Prime minister, Ubaidullah Sindhi the Minister for India, another Deobandi leader Moulavi Bashir its War Minister, and Champakaran Pillai was to be the Foreign Minister.[9] The Provisional Government of India obtained support from Galib Pasha and proclaimed Jihad against Britain. Recognition was sought from the Russian Empire, Republican China and Japan.[10] This provisional government would later attempt to obtain support from Soviet leadership. After the February Revolution in Russia in 1917, Pratap's government corresponded with the nascent Soviet government. In 1918, Mahendra Pratap met Trotsky in Petrograd before meeting the Kaiser in Berlin, urging both to mobilise against British India.[11][12]

However, these plans faltered, Emir Habibullah remained steadfastly neutral while he awaited a concrete indication where the war was headed, even as his advisory council and family members indicated their support against Britain. The Germans withdrew their support in 1917, but the 'Provisional Government of India' stayed behind at Kabul. In 1919, this government was ultimately dissolved under British diplomatic pressure on Afghanistan. Ubaidullah had stayed in Kabul for nearly seven years. He even encouraged the young King Amanullah Khan, who took power in Afghanistan after Habibullah's assassination, in the Third Anglo-Afghan War. The conclusion of the war, ultimately, forced Ubaidullah Sindhi to leave Afghanistan as King Amanullah came under pressure from Britain.[13]

Later works

Ubaidullah then proceeded from Afghanistan to Russia, where he spent seven months at the invitation of the Soviet leadership, and was officially treated as a guest of the state. During this period, he studied the ideology of socialism. According to an article in a major newspaper of Pakistan, titled 'Of socialism and Islam', "Islam showed not only deep sympathy for the poor and downtrodden but also condemned strongly the concentration of wealth in a number of Makkan surahs. Makkah, as an important centre of international trade, was home to the very rich (tribal chiefs) and the extremely poor."[13] In Russia, however, he was unable to meet Lenin who was severely ill at the time. Some people, at that time, thought that Sindhi was impressed by Communist ideals during his stay in Russia, however that is not true at all.[14] In 1923, Ubaidullah left Russia for Turkey where he initiated the third phase of the 'Shah Waliullah Movement' in 1924. He issued the 'Charter for the Independence of India' from Istanbul. Ubaidullah then left for Mecca, Arabia in 1927 and remained there until 1929. During this period, he brought the message of the rights of Muslims and other important religious issues to the people of Arabia. During his stay in Russia, he was not impressed by the Communist ideas but rather, after the Soviet revolution, he presented his belief to the Soviet government that: "Communism is not a natural law system but rather is a reaction to oppression, the natural law is offered by Islam". He attempted to convince them in a very systematic and logical manner. But he could not give an answer at that time, when he was asked to provide an example of a state which was being run according to the laws of Islam.

Literary works

Among his famous books are:

World outlook and philosophy

Ubaidullah Sindhi was of the view that the Quran uses Arabic words to make clear what God considers right and wrong. Other religious holy books like the Bible, the Gita and the Torah are also followed by many people around the world. He realized non-religious people (atheists) also existed in this world. After all he had spent some time among the communists in Russia. The individuals, who inaccurately interpreted the Bible and the Torah, were declared nonbelievers by Islam. In the same way, the person who incorrectly explains the Quran, can be declared an atheist. In Islam, the emphasis is clearly on God being eternal and everything in the universe belonging to Him alone. God alone is the Creator and Protector. It is evident from Ubaidullah Sindhi's travels around the world that he had an international and world outlook. It is also evident from his lifetime behavior and struggles that he wanted India not to be ruled by the British. He wanted India to be ruled by the Indians.[16]

Death

In 1936, the Indian National Congress requested his return to India, and the British Raj subsequently gave its permission. He landed at the port of Karachi from Saudi Arabia in 1938. He then went to Delhi, where he began a programme teaching Shah Waliullah’s Hujjatullahil Baalighah book to Maulana Saeed Ahmad Akbarabadi, who would then write an exegesis in his own words. Opposed to the partition of India, Ubaidullah led a conference supporting a united India in June 1941 at Kumbakonam.[17] Ubaidullah left for Rahim Yar Khan to visit his daughter in 1944. At the village 'Deen Pur' near Khanpur town in Rahim Yar Khan District, he was taken seriously ill and died on 21 August 1944.[1] He was buried in the graveyard adjacent to the grave of his mentors.

Legacy

- Pakistan Postal Services has issued a commemorative postage stamp in honor of Ubaidullah Sindhi in its 'Pioneers of Freedom' series in 1990.[1][18]

- Saeed Ahmad Akbarabadi wrote Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi awr Unke Naaqid.

References

- Profile and commemorative postage stamp image of Ubaidullah Sindhi on findpk.com website Retrieved 7 March 2019

- 'Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi remembered', Dawn (newspaper), Published 23 Aug 2008, Retrieved 6 March 2019

- Jalal 2007, p. 105

- Reetz 2007, p. 142

- Ansari 1986, p. 515

- Qureshi 1999, p. 78

- Qureshi 1999, pp. 77–82

- Hughes 2002, p. 469

- Ansari 1986, p. 516

- Andreyev 2003, p. 95

- Hughes 2002, p. 474

- Hughes 2002, p. 470

- Of socialism and Islam Dawn (newspaper), Published 8 July 2011, Retrieved 6 March 2019

- Sindhi, Ubaidullah. Shaoor o Aghai.

- farmannawaz.wordpress.com

- Ubaidullah Sindhi on wordpress.com website Published 1 February 2004, Retrieved 6 March 2019

- Ali, Afsar (17 July 2017). "Partition of India and Patriotism of Indian Muslims". The Milli Gazette. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- Ubaidullah Sindhi's commemorative postage stamp image and info listed on paknetmag.com website Retrieved 6 March 2019

Sources

- Ansari, K.H. (1986), Pan-Islam and the Making of the Early Indian Muslim Socialist. Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 20, No. 3. (1986), pp. 509-537, Cambridge University Press.

- Seidt, Hans-Ulrich (2001), From Palestine to the Caucasus-Oskar Niedermayer and Germany's Middle Eastern Strategy in 1918. German Studies Review, Vol. 24, No. 1. (Feb., 2001), pp. 1-18, German Studies Association, ISSN 0149-7952.

- Sims-Williams, Ursula (1980), The Afghan Newspaper Siraj al-Akhbar. Bulletin (British Society for Middle Eastern Studies), Vol. 7, No. 2. (1980), pp. 118-122, London, Taylor & Francis Ltd, ISSN 0305-6139.

- Engineer, Ashgar A (2005), They too fought for India's freedom: The Role of Minorities., Hope India Publications., ISBN 81-7871-091-9.

- Sarwar, Muḥammad (1976), Mawlānā ʻUbayd Allāh Sindhī : ʻālāt-i zandagī, taʻlīmāt awr siyāsī afkār, Lahore

- Sindhī, ʻUbaidullāh; Sarwar, Muḥammad (1970), Khutbāt o maqālāt-i Maulānā ʻUbaidullāh Sindhī. murattib Muḥammad Sarvar, Lāhaur, Sindh Sāgar Ikādamī