Chandra Shekhar Azad

Chandra Shekhar Azad (![]()

Shaheed Chandra Shekhar Azad | |

|---|---|

Chandra Shekhar Azad on a 1988 stamp of India | |

| Born | 23 July 1906 |

| Died | 27 February 1931 (aged 24) Allahabad, United Province, British India |

| Cause of death | Suicide by gunshot |

| Other names | Azad |

| Citizenship | Indian |

| Occupation | Revolutionary leader Freedom fighter Political activist |

| Organization | Hindustan Socialist Republican Association |

| Movement | Indian Independence Movement |

Early life and career

Azad was born as on 23 July 1906 in Bhabhra village (town) as Chandra Shekhar Tiwari , in the present-day Alirajpur district of Madhya Pradesh. His forefathers were from Badarka village near Kanpur (in present-day Unnao District). His mother, Jagrani Devi, was the third wife of Sitaram Tiwari, whose previous wives had died young. After the birth of their first son, Sukhdev, in Badarka, the family moved to Alirajpur State.[5][6]

His mother wanted her son to be a great Sanskrit scholar and persuaded his father to send him to Kashi Vidyapeeth, Banaras, to study. In December 1921, when Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi launched the Non-Cooperation Movement, Chandra Shekhar, then a 15-year-old student, joined. As a result, he was arrested. On being presented before a magistrate, he gave his name as "Azad" (The Free), his father's name as "Swatantrata" (Independence) and his residence as "Jail". From that day he came to be known as Chandra Shekhar Azad among the people.[7]

Revolutionary life

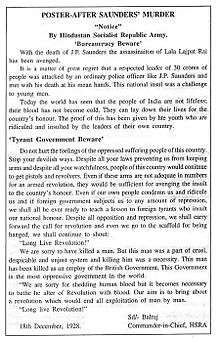

After the suspension of the non-cooperation movement in 1922 by Gandhi, Azad became more aggressive. He met a young revolutionary, Manmath Nath Gupta, who introduced him to Ram Prasad Bismil who had formed the Hindustan Republican Association (HRA), a revolutionary organisation. He then became an active member of the HRA and started to collect funds for HRA. Most of the fund collection was through robberies of government property. He was involved in the Kakori Train Robbery of 1925, in the attempt to blow up the Viceroy of India's train in 1926, and at last, the shooting of J. P. Saunders at Lahore in 1928 to avenge the killing of Lala Lajpat Rai.

Despite being a member of Congress, Motilal Nehru regularly gave money in support of Azad.[8]

Activities in Jhansi

Azad made Jhansi his organisation's hub for some time. He used the forest of Orchha, situated 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) from Jhansi, as a site for shooting practice and, being an expert marksman, he trained other members of his group. He built a hut near to a Hanuman temple on the banks of the Satar River and lived there under the alias of Pandit Harishankar Bramhachari for a long period. He taught children from the nearby village of Dhimarpura (now renamed Azadpura by the Government of Madhya Pradesh) and thus managed to establish good rapport with the local residents.

While living in Jhansi, he also learned to drive a car at the Bundelkhand Motor Garage in Sadar Bazar. Sadashivrao Malkapurkar, Vishwanath Vaishampayan and Bhagwan Das Mahaur came in close contact with him and became an integral part of his revolutionary group. The then congress leaders from Raghunath Vinayak Dhulekar and Sitaram Bhaskar Bhagwat were also close to Azad. He also stayed for sometime in the house of Rudra Narayan Singh at Nai Basti, as well as Bhagwat's house in Nagra.

One of his main supporters was Bundelkhand Kesri Dewan Shatrughan Singh, the founder of the freedom movement in Bundelkhand, he gave Azad financial as well as assistance with weapons and fighters. Azad visited his fort multiple times in Mangrauth.

With Bhagat Singh

The Hindustan Republican Association (HRA) was formed by Bismil, Jogesh Chandra Chatterjee, Sachindra Nath Sanyal Shachindra Nath Bakshi and Ashfaqulla Khan in 1924. In the aftermath of the Kakori train robbery in 1925, the British clamped down on revolutionary activities. Prasad, Ashfaqulla Khan, Thakur Roshan Singh and Rajendra Nath Lahiri were sentenced to death for their participation. Azad, Keshab Chakravarthy and Murari Sharma evaded capture. Chandra Shekhar Azad later reorganised the HRA with the help of revolutionaries like Sheo Verma and Mahaveer Singh.

Azad and Bhagat Singh secretly reorganised the Hindustan Republican Association (HRA) as the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA)in September 1928.[9] so as to achieve their primary aim of an independent India based on socialist principle. The insight of his revolutionary activities are described by Manmath Nath Gupta, a fellow member of HSRA in his numerous writings. Gupta has also written his biography titled "Chandrashekhar Azad" and in his book History of the Indian Revolutionary Movement (English version of above: 1972) he gave a deep insight about the activities of Azad and the ideology of Azad and HSRA.

Death

Azad died at Azad Park in Allahabad on 27 February 1931.[10] The police surrounded him in the park after Virbhadra Tiwari (their old companion who later turned traitor) informed them of his presence there. He was wounded in the process of defending himself and Sukhdev Raj (not to be confused with Sukhdev Thapar) and killed three policemen and wounded others. His actions made it possible for Sukhdev Raj to escape. He shot himself after being surrounded by the police and left with no option of escape after the ammunition was finished. Also, it is said that he used to keep a bullet to kill himself in the event of being caught by the British. The Colt pistol of Chandra Shekhar Azad is displayed at the Allahabad Museum.[11]

The body was sent to Rasulabad Ghat for cremation without informing the general public. As it came to light, people surrounded the park where the incident had taken place. They chanted slogans against British rule and praised Azad.[11]

Legacy

Alfred Park in Allahabad (officially Prayagraj), where Azad died, has been renamed Chandrashekhar Azad Park. Several schools, colleges, roads, and other public institutions across India are also named after him.

Starting from Manoj Kumar's 1965 film Shaheed, many films have featured the character of Azad. Manmohan played Azad in the 1965 film, Sunny Deol portrayed Azad in the movie 23rd March 1931: Shaheed, Azad was portrayed by Akhilendra Mishra in The Legend of Bhagat Singh and Raj Zutshi portrayed Azad in Shaheed-E-Azam.

Jawaharlal Nehru however in his autobiography writes that Azad met him a few weeks before his death, inquiring about possibility of not being considered an outlaw as a result of Gandhi-Irwin pact. He also saw the 'futility' of his methods and so did many of his associates, though not completely convinced of the 'peaceful methods'.[12]

The lives of Azad, Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, Bismil, and Ashfaq were depicted in the 2006 film Rang De Basanti, with Aamir Khan portraying Azad. The movie, which draws parallels between the lives of young revolutionaries such as Azad and Bhagat Singh, and today's youth, also dwells upon the lack of appreciation among today's Indian youth for the sacrifices made by these men.[13]

The 2018 television series Chandrashekhar chronicles the life of Chandra Shekhar Azad from his childhood to the legendary revolutionary leader. In the series young Chandrashekar Azad was portrayed by Ayaan Zubair, Azad in his teens by Dev Joshi and Adult Azad by Karan Sharma.[14]

References

- Chandra Shekar Azad (1906–1931). rrtd.nic.in

- Bhawan Singh Rana (1 January 2005). Chandra Shekhar Azad (An Immortal Revolutionary Of India). Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-288-0816-6. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- Chandrasekhar Azad at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- {{cite news|title=MMahatma Gandhi tried his best to save Bhagat Singh |url=https://www.thequint.com/voices/opinion/mahatma-gandhi-tried-his-best-to-save-bhagat-singhs-life |accessdate=4 September 2018 |publisher=The Quint} }

- The Calcutta review. University of Calcutta. Dept. of English. 1958. p. 44. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- Catherine B. Asher, ed. (June 1994). India 2001: reference encyclopedia. South Asia Publications. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-945921-42-4. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- Rana, Bhawan Singh (2005). Chandra Shekhar Azad (An Immortal Revolutionary of India). Diamond Pocket Books. pp. 22–24. ISBN 9788128808166.

- Mittal, S. K.; Habib, Irfan (June 1982). "The Congress and the Revolutionaries in the 1920s". Social Scientist. 10 (6): 20–37. JSTOR 3517065.

- Habib, Irfan (September 1997). "Civil Disobedience 1930–31". Social Scientist. 25 (9/10): 43–66. doi:10.2307/3517680. JSTOR 3517680.

- Bhattacherje, S. B. (1 May 2009). Encyclopaedia of Indian Events & Dates. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. B–19. ISBN 9788120740747. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Khatri, Ram Krishna (1983). Shaheedon Ki Chhaya Mein. Nagpur: Vishwabharati Prakashan. pp. 138–139.

- An Autobiography. Nehru, Jawaharlal. 1936. p. 262. ISBN 9780143031048.

- Is The Indian Script Unique. YouTube. Film Writers Association. 13 April 2012. Event occurs at 23:34. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- "This peace is the result of the sacrifice of freedom fighters like Azad: Ayaan Zubair". The Times of India. 31 March 2018.

Further reading

- Brahmdutt, Chandramani. Kranti Ki Laptain. ISBN 81-88167-30-4 (in Hindi)

- Krishnamurthy, Babu. Ajeya ("Unconquered"). Biography of Azad (in Kannada)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chandra Shekhar Azad. |