Royal Indian Navy mutiny

The Royal Indian Navy revolt (also called the Royal Indian Navy mutiny or Bombay mutiny) encompasses a total strike and subsequent revolt by Indian sailors of the Royal Indian Navy on board ship and shore establishments at Bombay harbour on 18 February 1946. From the initial flashpoint in Bombay, the revolt spread and found support throughout British India, from Karachi to Calcutta, and ultimately came to involve over 20,000 sailors in 78 ships and shore establishments.[1][2]

| Royal Indian Navy revolt | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Indian independence movement | ||||

| Date | 18–23 February 1946 | |||

| Location | British India | |||

| Goals | Better working conditions | |||

| Methods | General strike | |||

| Parties to the civil conflict | ||||

| Lead figures | ||||

| ||||

| Number | ||||

| ||||

The mutiny was repressed with force by British troops and Royal Navy warships. Total casualties were 8 dead and 33 wounded. Only the Communist Party supported the strikers; the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League condemned it.

The RIN Revolt: a brief history

The RIN Revolt started as a strike by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy on 18 February in protest against general conditions. The immediate issues of the revolt were living conditions and food.[3] By dusk on 19 February, a Naval Central Strike committee was elected. Leading Signalman Lieutenant M.S. Khan and Petty Officer Telegraphist Madan Singh were unanimously elected President and Vice-President respectively.[4] The strike found some support amongst the Indian population, though not their political leadership who saw the dangers of mutiny on the eve of Independence (see below).[5] The actions of the mutineers were supported by demonstrations which included a one-day general strike in Bombay. The strike spread to other cities, and was joined by elements of the Royal Indian Air Force and local police forces.

Indian Naval personnel began calling themselves the "Indian National Navy" and offered left-handed salutes to British officers. At some places, NCOs in the British Indian Army ignored and defied orders from British superiors. In Madras and Poona (now Pune), the British garrisons had to face some unrest within the ranks of the Indian Army. Widespread rioting took place from Karachi to Calcutta. Notably, the revolting ships hoisted three flags tied together – those of the Congress, Muslim League, and the Red Flag of the Communist Party of India (CPI), signifying the unity and downplaying of communal issues among the mutineers.

The revolt was called off following a meeting between the President of the Naval Central Strike Committee (NCSC), M. S. Khan, and Vallab Bhai Patel of the Congress, who had been sent to Bombay to settle the crisis. Patel issued a statement calling on the strikers to end their action, which was later echoed by a statement issued in Calcutta by Mohammed Ali Jinnah on behalf of the Muslim League. Under these considerable pressures, the strikers gave way. Arrests were then made, followed by courts martial and the dismissal of 476 sailors from the Royal Indian Navy. None of those dismissed were reinstated into either the Indian or Pakistani navies after independence.

Events of the revolt

The Second World War had caused rapid expansion of the Royal Indian Navy (RIN). In 1945, it was 10 times larger than its size in 1939. Due to war, as the army recruitment was no longer confined to martial races, men from different social strata were recruited. Between 1942 and 1945, the CPI leaders helped in carrying out mass recruitment of Indians especially communist activists into the British Indian army and RIN for war efforts against Nazi Germany. However once the war was over, the newly recruited men turned against the British.[6]

After the Second World War, three officers of the Indian National Army (INA), General Shah Nawaz Khan, Colonel Prem Sahgal and Colonel Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon were put on trial at the Red Fort in Delhi for "waging war against the King Emperor", i.e., the British sovereign personifying British rule. The three defendants were defended at the trial by Jawaharlal Nehru, Bhulabhai Desai and others. Outside the fort, the trials inspired protests and discontent among the Indian population, many of whom came to view the defendants as revolutionaries who had fought for their country. In January 1946 British airmen stationed in India took part in the Royal Air Force Revolt of 1946 mainly over the slow speed of their demobilisation, but also in some cases issuing demands against being used in support of continued British colonial rule. The Viceroy at the time, Lord Wavell, noted that the actions of the British airmen had influenced both the RIAF and RIN mutinies, commenting "I am afraid that [the] example of the Royal Air Force, who got away with what was really a mutiny, has some responsibility for the present situation."

The revolt was initiated by the ratings of the Royal Indian Navy on 18 February 1946. It was a reaction to the treatment meted out to ratings in general and the lack of service facilities in particular. On 16 January 1946, a contingent of 67 ratings of various branches arrived at Castle Barracks, Mint Road, in Fort Mumbai. This contingent had arrived from the basic training establishment, HMIS Akbar, located at Thane, a suburb of Bombay, at 1600 in the evening. One of them Syed Maqsood Bokhari went to the officer on duty and informed him about issues involving the galley (kitchen) staff at the training establishment.

The sailors were that evening alleged to have been served sub-standard food. Only 17 ratings took the meal, the rest of the contingent went ashore to eat in an open act of defiance. It has since been said that such acts of neglect were fairly regular, and when reported to senior officers present practically evoked no response, which certainly was a factor in the buildup of discontent. The ratings of the communication branch in the shore establishment, HMIS Talwar, drawn from higher strata of society, harboured a high level of revulsion towards the authorities, having complained of neglect of their facilities fruitlessly.

The INA trials, the stories of Subhas Chandra Bose ("Netaji"), as well as the stories of INA's fight during the Siege of Imphal and in Burma were seeping into the glaring public-eye at the time. These, received through the wireless sets and the media, fed discontent and ultimately inspired the sailors to strike. In Karachi, revolt broke out on board the Royal Indian Navy ship, HMIS Hindustan off Manora Island. The ship, as well as shore establishments were taken over by mutineers. Later, it spread to the HMIS Bahadur. A naval central strike committee was formed on 19 February 1946, led by M. S. Khan and Madan Singh. The next day, ratings from Castle and Fort Barracks in Bombay, joined in the revolt when rumours (which were untrue) spread that HMIS Talwar's ratings had been fired upon.

Ratings left their posts and went around Bombay in lorries, holding aloft flags containing the picture of Subhas Chandra Bose and Lenin. Several Indian naval officers who opposed the strike and sided with the British were thrown off the ship by ratings. Soon, the mutineers were joined by thousands of disgruntled ratings from Bombay, Karachi, Cochin and Vizag. Communication between the various mutinies was maintained through the wireless communication sets available in HMIS Talwar. Thus, the entire revolt was coordinated. The strike by the Naval ratings soon took serious proportions. Hundreds of strikers from the sloops, minesweepers and shore establishments in Bombay demonstrated for two hours along Hornby Road near VT (now the very busy D.N. Road near CST). British personnel of the Defence forces were singled out for attacks by the strikers who were armed with hammers, crowbars and hockey sticks. The White Ensign was lowered from the ships.

In Flora Fountain, vehicles carrying mail were stopped and the mail burnt. British men and women going in cars and victorias were made to get down and shout "Jai Hind" (Victory to India). Guns were trained on the Taj Mahal Hotel, the Yacht Club and other buildings from morning till evening. After the outbreak of the mutiny, the first thing the mutineers did was to free Balai Chand Dutta (who was arrested during General Auchinleck’s visit). Then they took possession of Butcher Island (where the entire ammunition meant for Bombay Presidency was stocked).

1,000 RIAF men from the Marine Drive and Andheri Camps also joined in sympathy.

The strike soon spread to other parts of India. The ratings in Calcutta, Madras, Karachi and Vizag also went on strike with the slogans "Strike for Bombay", "Release 11,000 INA prisoners" and "Jai Hind".

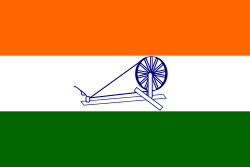

On 19 February, the Tricolour was hoisted by the ratings on most of the ships and establishments. By 20 February, the third day, armed British destroyers had positioned themselves off the Gateway of India. The RIN Revolt had become a serious crisis for the British government. An alarmed Clement Attlee, the British Prime Minister, ordered the Royal Navy to put down the revolt. Admiral J.H. Godfrey, the Flag Officer commanding the RIN, went on air with his order to "Submit or perish". The movement had, by this time, inspired by the patriotic fervour sweeping the country, started taking a political turn.

The naval ratings' strike committee decided, in a confused manner, that the HMIS Kumaon had to leave Bombay harbour while HMIS Kathiawar was already in the Arabian Sea under the control of mutineering ratings. At about 1030 Kumaon suddenly let go the shore ropes, without even removing the ships' gangway while officers were discussing the law and order situation on the outer breakwater jetty. However, within two hours fresh instructions were received from the strikers' control room and the ship returned to the same berth.

The situation was changing fast and rumours spread that Australian and Canadian armed battalions had been stationed outside the Lion gate and the Gun gate to encircle the dockyard where most ships were berthed. However, by this time, all the armouries of the ships and establishments had been seized by the striking ratings. The clerks, cleaning hands, cooks and wireless operators of the striking ship armed themselves with whatever weapon was available to resist the British destroyers that had sailed from Trincomalee in Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

The third day dawned charged with fresh emotions. The Royal Air Force flew a squadron of bombers low over Bombay harbour in a show of force, as Admiral Arthur Rullion Rattray, Flag Officer, Bombay, RIN, issued an ultimatum ordering the ratings to raise black flags and surrender unconditionally.

In Karachi, realising that using Indian troops against Indian sailors would place stress on the morale and discipline of the former, the 2nd Battalion of the Black Watch had been called from their barracks. The first priority was to deal with the revolt on Manora Island. Ratings holding the Hindustan opened fire when attempts were made to board the ship. At midnight, the 2nd Battalion was ordered to proceed to Manora, expecting resistance from the Indian naval ratings who had taken over the shore establishments HMIS Bahadur, Chamak and Himalaya and from the Royal Naval Anti-Aircraft School on the island. The Battalion was ferried silently across in launches and landing craft. D company was the first across, and they immediately proceeded to the southern end of the island to Chamak. The remainder of the Battalion stayed at the southern end of the Island. By the morning, the British soldiers had secured the island.

Confrontation with the Hindustan

The decision was made to confront the Indian naval ratings on board the destroyer Hindustan, armed with 4-in. guns. During the morning three guns (caliber unknown) from the Royal Artillery C. Troop arrived on the island. The Royal Artillery positioned the battery within point blank range of the Hindustan on the dockside. An ultimatum was delivered to the mutineers aboard Hindustan, stating that if they did not the leave the ship and put down their weapons by 10:30 they would have to face the consequences. The deadline came and went and there was no message from the ship or any movement.

Orders were given to open fire at 10:33. The gunners' first round was on target. On board the Hindustan the Indian naval ratings began to return gunfire and several shells whistled over the Royal Artillery guns. Most of the shells fired by the Indian ratings went harmlessly overhead and fell on Karachi itself. They had not been primed so there were no casualties. However, the mutineers could not hold on. At 10:51 the white flag was raised. British naval personnel boarded the ship to remove casualties and the remainder of the mutinous crew. Extensive damage had been done to Hindustan's superstructure and there were many casualties among the Indian sailors.

HMIS Bahadur was still under the control of mutineers. Several Indian naval officers who had attempted or argued in favour of putting down the revolt were thrown off the ship by ratings. The 2nd Battalion was ordered to storm the Bahadur and then proceed to storm the shore establishments on Manora island. By the evening D company was in possession of the A A school and Chamak, B company had taken the Himalaya, while the rest of the Battalion had secured Bahadur. The revolt in Karachi had been put down.

In Bombay, the guncrew of a 25-pounder gun fitted in an old ship had by the end of the day fired salvos towards the Castle barracks. Patel had been negotiating fervently, and his assurances did improve matters considerably. However, it was clear that the revolt was fast developing into a spontaneous movement with its own momentum. By this time the British destroyers from Trincomalee had positioned themselves off the Gateway of India. The negotiations moved fast, keeping in view the extreme sensitivity of the situation and on the fourth day most of the demands of the strikers were conceded in principle.

Immediate steps were taken to improve the quality of food served in the ratings' kitchen and their living conditions. The national leaders also assured that favorable consideration would be accorded to the release of all the prisoners of the Indian National Army.

Casualties and dismissals

Total fatalities arising from the mutiny were seven RIN sailors and one officer killed. Thirty-three RIN personnel and British soldiers were injured.[7] A total of 476 sailors were discharged from the RIN as a result of the outbreak.

Many sailors in HMIS Talwar were reported to have Communist leanings and on a search of 38 sailors who were arrested in the HMIS New Delhi, 15 were found to be subscribers of CPI literature. The British later came to know that the revolt, though not initiated by the Communist Party of India, was inspired by its literature.[8]

Lack of support

The mutineers in the armed forces got no support from the national leaders and were largely leaderless. Mahatma Gandhi, in fact, condemned the riots and the ratings' revolt. His statement on 3 March 1946 criticized the strikers for revolting without the call of a "prepared revolutionary party" and without the "guidance and intervention" of "political leaders of their choice".[9] He further criticized the local Indian National Congress leader Aruna Asaf Ali, who was one of the few prominent political leaders of the time to offer support for the mutineers, stating that she would rather unite Hindus and Muslims on the barricades than on the constitutional front.[10] Gandhi's criticism also belies the submissions to the looming reality of Partition of India, having stated "If the union at the barricade is honest then there must be union also at the constitutional front."[11]

The Muslim League made similar criticisms of the mutiny, arguing that unrest amongst the sailors was not best expressed on the streets, however serious their grievances might be. Legitimacy could only, probably, be conferred by a recognised political leadership as the head of any kind of movement. Spontaneous and unregulated upsurges, as the RIN strikers were viewed, could only disrupt and, at worst, destroy consensus at the political level. This may be Gandhi's (and the Congress's) conclusions from the Quit India Movement in 1942 when central control quickly dissolved under the impact of British repression, and localised actions, including widespread acts of sabotage, continued well into 1943. It may have been the conclusion that the rapid emergence of militant mass demonstrations in support of the sailors would erode central political authority if and when transfer of power occurred. The Muslim League had observed passive support for the "Quit India" campaign among its supporters and, devoid of communal clashes despite the fact that it was opposed by the then collaborationist Muslim League. It is possible that the League also realised the likelihood of a destabilised authority as and when power was transferred. This certainly is reflected on the opinion of the sailors who participated in the strike.[12] It has been concluded by later historians that the discomfiture of the mainstream political parties was because the public outpourings indicated their weakening hold over the masses at a time when they could show no success in reaching agreement with the British Indian government.[13]

The Communist Party of India, the third largest political force at the time, extended full support to the naval ratings and mobilised the workers in their support, hoping to end British rule through revolution rather than negotiation.[14] The two principal parties of British India, the Congress and the Muslim League, refused to support the ratings. The class content of the mass uprising frightened them and they urged the ratings to surrender. Patel and Jinnah, two representative faces of the communal divide, were united on this issue and Gandhi also condemned the 'Mutineers'. The Communist Party gave a call for a general strike on February 22. There was an unprecedented response and over a lakh students and workers came out on the streets of Calcutta, Karachi and Madras. The workers and students carrying red flags paraded the streets with slogans : 'Accept the demands of the ratings', 'End British and Police zoolum'. Upon surrender, the ratings faced court-martial, imprisonment and victimisation. Even after 1947, the governments of Independent India and Pakistan refused to reinstate them or offer compensation. The only prominent leader from Congress who supported them was Aruna Asaf Ali. Disappointed with the progress of the Congress Party on many issues, Aruna Asaf Ali joined the Communist Party of India(CPI) in the early 1950s.[15]

It has been speculated that the actions of the Communist Party to support the mutineers was partly born out of its nationalist power struggle with the Indian National Congress. M. R. Jayakar, who was a Judge in the Federal Court of India (which later became the Supreme Court of India), wrote in a personal letter [16]

There is a secret rivalry between the Communists and Congressmen, each trying to put the other in the wrong. In yesterday’s speech Vallabhbhai almost said, without using so many words, that the trouble was due to the Communists trying to rival the Congress in the manner of leadership.

The only major political segment that still mentions the revolt are the Communist Party of India . The literature of the communist party portrays the RIN Revolt as a spontaneous nationalist uprising that had the potential to prevent the partition of India, and one that was essentially betrayed by the leaders of the nationalist movement.[17]

More recently, the RIN Revolt has been renamed the Naval Uprising and the mutineers honoured for the part they played in India's independence. In addition to the statue which stands in Mumbai opposite the sprawling Taj Wellingdon Mews, two prominent mutineers, Madan Singh and B.C. Dutt, have each had ships named after them by the Indian Navy.

Legacy and assessments of the effects of the revolt

Indian historians have looked at the mutiny as a revolt against the British Raj and imperial rule. British scholars note that there was no comparable unrest in the Army, and concluded that internal conditions in the Navy were central. There was poor leadership and a failure to instill any belief in the legitimacy of their service. Furthermore, there was tension between officers (often British), petty officers (largely Punjabi Muslims), and junior ratings (mostly Hindu), as well as anger at the very slow rate of release from wartime service.[18][19]

The grievances focused on the slow pace of demobilisation. British units were near mutiny and it was feared that Indian units might follow suit.[20] The weekly intelligence summary issued on 25 March 1946 admitted that the Indian Army, Navy and Air Force units were no longer trustworthy, and, for the Army, "only day to day estimates of steadiness could be made".[21] The situation has thus been deemed the "Point of No Return."[22][23]

The British in 1948 branded the 1946 Indian Naval Mutiny as a “larger communist conspiracy raging from the Middle East to the Far East against the British crown”.[24]

However, probably just as important remains the question as to what the implications would have been for India's internal politics had the revolt continued. The Indian nationalist leaders, most notably Gandhi and the Congress leadership, had apparently been concerned that the revolt would compromise the strategy of a negotiated and constitutional settlement, but they sought to negotiate with the British and not within the two prominent symbols of respective nationalism—-the Congress and the Muslim League.[25]

In 1967 during a seminar discussion marking the 20th anniversary of Independence; it was revealed by the British High Commissioner of the time John Freeman, that the mutiny of 1946 had raised the fear of another large scale mutiny along the lines of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, from the 2.5 million Indian soldiers who had participated in the Second World War. The mutiny had accordingly been a large contributing factor to the British deciding to leave India. "The British were petrified of a repeat of the 1857 Mutiny, since this time they feared they would be slaughtered to the last man".[26][27]

In popular culture

The rising was championed by Marxist cultural activists from Bengal. Salil Chaudhury wrote a revolutionary song in 1946 on behalf of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). Later, Hemanga Biswas, another veteran of the IPTA, penned a commemorative tribute. A Bengali play based on the incident, Kallol (Sound of the Wave), by radical playwright Utpal Dutt, became an important anti-establishment statement, when it was first performed in 1965 in Calcutta. It drew large crowds to the Minerva Theatre where it was being performed; soon it was banned by the Congress government of West Bengal and its writer imprisoned for several months.[28][29]

The revolt is part of the background to John Masters' Bhowani Junction whose plot is set at this time. Several Indian and British characters in the book discuss and debate the revolt and its implications.

The 2014 Malayalam movie Iyobinte Pusthakam directed by Amal Neerad features the protagonist Aloshy (Fahadh Faasil) as a Royal Indian Navy mutineer returning home along with fellow mutineer and National Award-winning stage and film actor P. J. Antony (played by director Aashiq Abu)

See also

Naval mutinies:

Notes and references

- Spence, Daniel Owen (27 May 2015). "Beyond Talwar: A Cultural Reappraisal of the 1946 Royal Indian Navy Mutiny". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 43 (3): 489–508. doi:10.1080/03086534.2015.1026126. ISSN 0308-6534.

- Notes on India By Robert Bohm.pp213

- "Mumbai and the Great Naval Mutiny". Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Encyclopaedia of Political Parties. By O.P. Ralhan pp1011 ISBN 81-7488-865-9

- Glimpses of Indian National Movement. By Abel M. pp257.ISBN 81-7881-420-X

- The Great Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 By Javed Iqbal

- Singh, Satyindra (1992). Blueprint to Bluewater. p. 31. ISBN 978-81-7062-148-5.

- The Unsung Heroes of 1946 by Ajit J(Mainstream Weekly)

- Chandra, Bipan and others (1989). India's Struggle for Independence 1857–1947, New Delhi:Penguin, ISBN 0-14-010781-9, p.485

- Jawaharlal Nehru, a Biography. By Sankar Ghose. pp141

- Bipan Chandra and others, 'Indian Struggle for Independence' (New Delhi, Penguin, 1988), p. 486

- Subrata Banerjee, The RIN Strike (New Delhi, People’s Publishing House,1954).

- James L. Raj; Making and unmaking of British India. Abacus. 1997. p598

- Meyer, John (13 December 2016). "The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946: Nationalist Competition and Civil-Military Relations in Postwar India". Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 45: 46–69. doi:10.1080/03086534.2016.1262645.

- The Great Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 By Javed Iqbal

- Meyer, JM (2016). "The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946: Nationalist Competition and Civil-Military Relations in Postwar India". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 45 (1): 46–69. doi:10.1080/03086534.2016.1262645.

- Subrata Banerjee, The RIN Strike (New Delhi, People’s Publishing House,1954) The RIN uprising would have developed in a different direction; had it not been for the policy pursued by them in relation to every struggle that broke out in that period, we would have seen something different from the 1947 transfer of power, according to which the iron grip of British rule was allowed to continue. p.xvii, Introduction by E. M. S. Namboodiripad

- Ronald Spector, "The Royal Indian Navy Strike of 1946", Armed Forces and Society (Winter 1981) 7#2 pp 271–284

- Daniel Owen Spence, "Beyond Talwar: A Cultural Reappraisal of the 1946 Royal Indian Navy Mutiny." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 43.3 (2015): 489-508.

- James L. Raj; Making and unmaking of British India. Abacus. 1997. p596

- Unpublished, Public Relations Office, London. War Office. 208/761A; James L. Raj; Making and unmaking of British India. Abacus. 1997. p598.

- Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez, and Decolonization. By William Roger Louis.pp405

- Britain Since 1945: A Political History By David Childs.pp 28

- "Remembering the naval mutiny 70 years ago when the British nearly blew up Bombay".

- Bipan Chandra and others, ‘Indian Struggle for Independence’ (New Delhi, Penguin, 1988), p. 486

- Aiyar, Swaminathan S Anklesaria (15 August 2007). "Swaminathan S Anklesaria Aiyar: Freedom, won by himsa or ahimsa?". Economic Times.

- Doctor, Vikram (15 August 2007). "In the 70th year of Independence, here is a look back at the long forgotten 1946 RIN Mutiny in Mumbai". Economic Times.

- Inside the actor’s mind Mint (newspaper), 3 July 2009.

- Remembering Utpal Dutt Shoma A Chatterji, Screen (magazine), 20 August 2004.

Further reading

- Spector, Ronald. "The Royal Indian Navy Strike of 1946," Armed Forces and Society (Winter 1981) 7#2 pp 271–284

- Bell, Christopher M. Naval Mutinies of the Twentieth Century: An International Perspective pp212–232. ISBN 0-7146-8468-6

- Metcalf, Barbara Daly, and Thomas R. Metcalf. A Concise History of Modern India ISBN 0-521-86362-7

External links

- 'The Tribune: RIN Revolt – The lesser known revolt

- 'Madan Singh and B.C Dutt honoured at last'

- 'Interview with Madan Singh, Vice president of the Central Strike Committee'

- 'Goodbye to Madan the Mutineer'

- '60th anniversary of RIN revolt'

- http://www.indiannavy.nic.in/under2ensigns.pdf

- Centre for South Asian Studies, School of Social & Political Studies, University of Edinburgh, http://www.csas.ed.ac.uk/index.php.

.

https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/rin-upsurge-when-indian-naval-sailors-rose-in-revolt-against-the-raj-6274531/