Bahawalpur

Bahawalpur (بہاولپور), is a city located in the Punjab province of Pakistan. Bahawalpur is the 11th largest city in Pakistan by population as per 2017 census with a population of 762,111.[5]

Bahawalpur بہاولپور | |

|---|---|

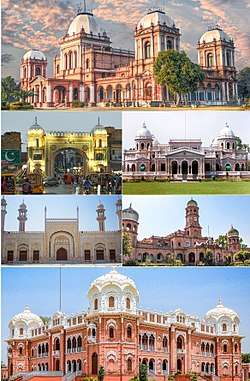

Clockwise from top: Noor Mahal Palace, Gulzar Mahal, Sadiq Dane High School, Darbar Mahal Palace, Sadiq Mosque, Fareed Gate | |

Municipal Corporation logo | |

Bahawalpur  Bahawalpur | |

| Coordinates: 29°23′44″N 71°41′1″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Division | Bahawalpur |

| District | Bahawalpur |

| Union councils | 21 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Corporation |

| • Mayor | Aqeel-ul-Najam (Aqeel Najam Hashmi) |

| • Deputy Mayor | Malik Munir Iqbal Channar |

| Area | |

| • City | 246 km2 (95 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 24,830 km2 (9,590 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 181 m (702 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City | 762,111 |

| • Density | 3,100/km2 (8,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PKT) |

| Postal code type | 63100 |

| Area code(s) | 062 |

| HDI (2017) | |

| Website | Bahawalpur / Punjab Portal |

Founded in 1748, Bahawalpur was the capital of the former princely state of Bahawalpur, ruled by the Abbasi family of Nawabs until 1955. The Nawabs left a rich architectural legacy, and Bahawalpur is now known for its monuments dating from that period.[6] The city also lies at the edge of the Cholistan Desert, and serves as the gateway to the nearby Lal Suhanra National Park.

History

%2C_Bahawalpur.jpg)

Early history

The area known as Bahawalpur State was home to various ancient societies. The Bahawalpur region contains ruins from the Indus Valley Civilisation, as well as ancient Buddhist sites such as the nearby Patan minara.[8] British archaeologist Sir Alexander Cunningham identified the Bahawalpur region as home of the Yaudheya kingdoms of the Mahābhārata.[9][10] Prior to the establishment of Bahawalpur, the region's major city was the holy city of Uch Sharif - a regional metropolitan centre between the 12th and 17th centuries that is renowned for its collection of historic shrines dedicated to Muslim mystics from the 12-15th centuries built in the region's vernacular style.[11]

Founding

Bahawalpur was founded in 1748 by Nawab Bahawal Khan I,[12] after migrating to the region around Uch from Shikarpur, Sindh.[13] Bahawalpur replaced Derawar as the clan's capital city.[14] The city had initially flourished as a trading post on trade routes between Afghanistan and central India.[15]

In 1785, the Durrani commander Sirdar Khan attacked Bahawalpur city and destroyed many of its buildings on behalf of Mian Abdul Nabi Kalhora of Sindh.[16] Bahawalpur's ruling family, along with nobles from nearby Uch, were forced to take refuge in the Derawar Fort, where they successfully repulsed attacks.[16] The attacking Durrani force accepted 60,000 rupees as nazrana tribute, though Bahawal Khan later had to seek refuge in the Rajput states as the Afghan Durranis occupied Derawar Fort.[16] Bahawal Khan returned to conquer the fort by way of Uch, and re-established control of Bahawalpur.[16]

Princely state

The princely state of Bahawalpur was founded in 1802 by Nawab Mohammad Bahawal Khan II after the break-up of the Durrani Empire, and was based in the city. In 1807, Ranjit Singh of the Sikh Empire laid siege to the fort in Multan, prompting refugees to seek safety in Bahawalpur in the wake of his marauding forces that began to attack the countryside around Multan.[16] Ranjit Singh eventually withdrew the siege, and gifted the Nawab of Bahawalpur some gifts as the Sikh forces retreated.[16]

Bahalwapur offered an outpost of stability in the wake of crumbling Mughal rule and declining power of Khorasan's monarchy.[16] The city became a refuge for prominent families from affected regions, and also saw an influx of religious scholars escaping the consolidation of Sikh power in Punjab.[16]

Fearing an invasion from the Sikh Empire,[17] Nawab Mohammad Bahawal Khan III signed a treaty with the British on 22 February 1833, guaranteeing the independence of the Nawab and the autonomy of Bahawalpur as a princely state. The treaty guaranteed the British a friendly southern frontier during their invasion of the Sikh Empire.[17]

Trade routes had shifted away from Bahawalpur by the 1830s, and British visitors to the city noted several empty shops in the city's bazaar.[15] The population at this time was estimated to be 20,000,[15] and was noted to be made up primarily of low-caste Hindus.[15] Also in 1833, the Sutlej and Indus Rivers were opened to navigation, allowing goods to reach Bahawalpur.[16]

By 1845, newly opened trade routes to Delhi re-established Bahawalpur as a commercial centre.[16] The city was known in the late 19th century as a centre for the production of silk goods, lungis, and cotton goods.[18] The city's silk was noted to be of higher quality than silk works from Benares or Amritsar.[15]

An 1866 crisis over succession to the Bahawalpur throne markedly increased British influence in the princely state.[19] Bahawalpur was constituted as a municipality in 1874.[20] The city's Noor Mahal palace was completed in 1875.[14] In 1878, Bahawalpur's 4,285-foot long Empress Bridge was opened as the only rail crossing over the Sutlej River.[14] Bahawalpur's Sadiq Egerton College was founded in 1886.[14] Bahalwapur's Nawabs celebrated the Golden Jubillee of Queen Victoria in 1887 in a state function at the Noor Mahal palace.[18] Two hospitals were established in the city in 1898.[14] In 1901, the population of the city was 18,546.[14]

Bahawalpur's Islamia University was founded as Jamia Abbasia in 1925. At the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Bahawalpur's Nawab was the first ruler of a princely state to offer his full support and resources of the state towards the crown's war efforts.[21]

Joining Pakistan

British Princely states were given the option to join either Pakistan or India upon withdrawal of British suzerainty in August 1947. The city and princely state of Bahawalpur acceded to Pakistan on 7 October 1947 under Nawab Sadiq Muhammad Khan Abbasi V Bahadur. Following independence, the city's minority Hindu and Sikh communities largely migrated to India en masse, while Muslim refugees from India settled in the city and surrounding region. The city's Quaid-e-Azam Medical College was founded in 1971. While much of southern Punjab's population in Multan support the Pakistan Peoples Party, the region around Bahawalpur is known for its support of the Pakistan Muslim League.[22]

Economy

The main crops for which Bahawalpur is recognised are cotton, sugarcane, wheat, sunflower seeds, rape/mustard seed and rice. Bahawalpur mangoes, citrus, dates and guavas are some of the fruits exported out of the country. Vegetables include onions, tomatoes, cauliflower, potatoes and carrots. Being an expanding industrial city, the government has revolutionised and liberalised various markets allowing the caustic soda, cotton ginning and pressing, flour mills, fruit juices, general engineering, iron and steel re-rolling mills, looms, oil mills, poultry feed, sugar, textile spinning, textile weaving, vegetable ghee and cooking oil industries to flourish.[23]

Demographics

According to the 2017 Census of Pakistan, the city's population was recorded to have risen to 762,111 from 408,395 in 1998.[5] The Bakhri are a clan found in the Shabr Farid ilaqa of Bahawalpur claiming Rajput origin. They were previously converted to Islam but fearing to return to their Hindu roots they settled down in Multan as weavers.[24]

Civic administration

Bahawalpur was announced as one of six cities in Punjab whose security would be improved by the Punjab Safe Cities Authority. 5.6 billion Rupees have been allocated for the project,[26] which will be modeled along the lines of the Lahore Safe City project in which 8,000 CCTV cameras were installed throughout the city at a cost of 12 billion rupees to record and send images to Integrated Command and Control Centres.[27]

Sports

Bahawal Stadium or The Bahawalpur Dring Stadium is a multipurpose stadium, home to Bahawalpur Stags. It hosted a sole international match, a test match between Pakistan and India in 1955. Motiullah hockey stadium is in Bahawal Stadium which is used for various national and international hockey tournaments in country. Aside from the cricket ground, it has a gym and a pool facility for the citizens. There are also great tennis courts which are under administration of bahawalpur tennis club. There is also a 2 kilometer jogging track around the football ground.

Notable people

- Former field hockey player, Samiullah Khan, was born in the city.[28]

- Former Member of National Assembly Nawab Salahuddin Abbasi.

- Member of the Provincial Assembly of Punjab, Samiullah Chaudhary, was born in the city.[29]

- Former member of the National Assembly of Pakistan and elected member of the Provincial Assembly of Punjab, Mumtaz Jajja.

- Disabled Cricket Team Player Muhammad Zubair Saleem[30]

- Former journalist, presenter and producer at the BBC World Service, Durdana Ansari, OBE, was born in the city.

See also

References

- "MC Bahawalpur". MC Bahawalpur. Archived from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- https://www.citypopulation.de/php/pakistan-distr-admin.php?adm2id=70305

- "DISTRICT AND TEHSIL LEVEL POPULATION SUMMARY WITH REGION BREAKUP: PUNJAB" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. 3 January 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- https://www.undp.org/content/dam/pakistan/docs/HDR/HDI%20Report_2017.pdf

- http://www.citypopulation.de/Pakistan-100T.html

- Dar, Shujaat Zamir (2007). Sights in the Sands of Cholistan: Bahawalpur's History and Architecture. Oxford University Press.

- "A century later, Bahawalpur's Darbar Mahal stands tall - The Express Tribune". 21 April 2017.

- Auj, Nūruzzamān (1987). Ancient Bahawalpur. Caravan Book Centre.

- Gupta, Parmanand (1989). Geography from Ancient Indian Coins & Seals. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 9788170222484.

- North Indian Inscriptions volume III: Inscriptions of the Early Gupta Kings. p. 23.

- "UNESCO Office in Bangkok: Uch Monument". www.unescobkk.org. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Wright, Arnold, ed. (1922). Indian States: A Biographical, Historical, and Administrative Survey. Asian Educational Services. p. 145. ISBN 9788120619654.

- Gilmartin, David (5 June 2015). Blood and Water: The Indus River Basin in Modern History. Univ of California Press. ISBN 9780520285293.

- Cotton, James Sutherland; Burn, Sir Richard; Meyer, Sir William Stevenson (1908). Imperial Gazetteer of India ... Clarendon Press.

- The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and Its Dependencies. Black, Parbury, & Allen. 1838.

- Álī, Shahāmat (1848). The History of Bahawalpur: With Notices of the Adjacent Countries of Sindh, Afghanistan, Multan, and the West of India. James Madden.

- Burki, Shahid Javed (19 March 2015). Historical Dictionary of Pakistan. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442241480.

- bahādur.), Muḥammad Laṭīf (Saiyid, khān (1891). History of the Panjáb from the Remotest Antiquity to the Present Time. Calcutta Central Press Company, limited.

- Minahan, James (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598846591.

- "Bahawalpur | Pakistan". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Javaid, Umbreen (2004). Politics of Bahawalpur: From State to Region, 1947-2000. Classic.

- Bianchi, Robert (9 September 2004). Guests of God: Pilgrimage and Politics in the Islamic World. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780195171075.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 September 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Denzil Ibbetson, K.C.S.I. (1911). A glossary of the tribes and castes of the Punjab and North-West frontier province: a-k, volume 2. p. 93.

- Jones, Justin; Qasmi, Ali Usman (13 April 2015). The Shi'a in Modern South Asia: Religion, History and Politics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781316338872.

- "After Lahore, six others to become 'safer cities'". Express Tribune. 20 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- "Punjab Safe City Project inaugurated". Dawn. 12 October 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- "Profile". Punjab Assembly. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- Ahmed, Ali (30 July 2019). "Pakistan disabled cricketers to leave for England". Business Recorder. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

Bibliography

- Moj, Muhammad (2015), The Deoband Madrassah Movement: Countercultural Trends and Tendencies, Anthem Press, ISBN 978-1-78308-389-3

- Talbot, Ian (2015), "Introduction", in Roger D. Long; Gurharpal Singh; Yunas Samad; Ian Talbot (eds.), State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security, Routledge, pp. 1–, ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4

- Zahab, Mariam Abou; Roy, Olivier (2004) [first published in French in 2002]. Islamist Networks: The Afghan-Pakistan Connection. Translated by King, John. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-704-0.

External links

- Bahawalpur at Curlie