Charles Aznavour

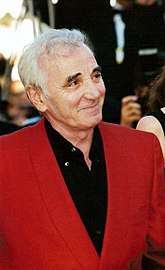

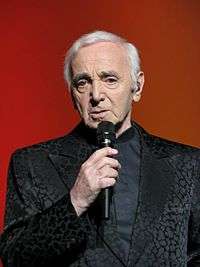

Charles Aznavour (/ˌæznəˈvʊər/ AZ-nə-VOOR, French: [ʃaʁl aznavuʁ]; born Shahnour Vaghinag Aznavourian, Armenian: Շահնուր Վաղինակ Ազնավուրյան, Shahnur Vaghinak Aznavuryan; 22 May 1924 – 1 October 2018)[1][upper-alpha 1] was a French and Armenian[4] singer, lyricist, actor and diplomat. Aznavour was known for his distinctive tenor[5] voice: clear and ringing in its upper reaches, with gravelly and profound low notes. In a career as a composer, singer and songwriter, spanning over 70 years, he recorded approximately more than 1,200 songs interpreted in 9 languages.[6] Moreover, he wrote or co-wrote more than 1,000 songs for himself and others.

Charles Aznavour | |

|---|---|

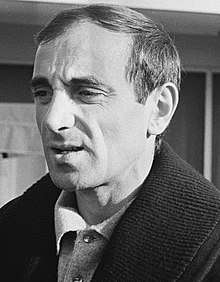

Aznavour in 1963 | |

| Born | Shahnour Varinag Aznavourian 22 May 1924 |

| Died | 1 October 2018 (aged 94) |

| Burial place | Montfort-l'Amaury (Yvelines), France |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1933–2018 |

| Spouse(s) | Micheline Rugel

( m. 1946; div. 1952)Evelyne Plessis

( m. 1956; div. 1960)Ulla Thorsell

( m. 1967) |

| Children | 5, including Seda Aznavour |

| Awards | Legion of Honour (1997, 2001 and 2004) See Awards and recognition |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Labels | |

| Website | charlesaznavour |

Aznavour was one of France's most popular and enduring singers.[7][8] He sold 180 million records[9][10][11][12] during his lifetime and was dubbed France's Frank Sinatra,[13][14] while music critic Stephen Holden described Aznavour as a "French pop deity".[15] He was also arguably the most famous Armenian of his time.[7][16] In 1998, Aznavour was named Entertainer of the Century by CNN and users of Time Online from around the globe. He was recognized as the century's outstanding performer, with nearly 18% of the total vote, edging out Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan.[17] Jean Cocteau once said: "Before Aznavour despair was unpopular".[18]

Aznavour sang for presidents, popes and royalty, as well as at humanitarian events. In response to the 1988 Armenian earthquake, he founded the charitable organization Aznavour for Armenia along with his long-time friend impresario Levon Sayan. In 2009, he was appointed ambassador of Armenia to Switzerland, as well as Armenia's permanent delegate to the United Nations at Geneva.[19]

He started his last world tour in 2014. On 24 August 2017, Aznavour was awarded the 2,618th star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Later that year, he and his sister were awarded the Raoul Wallenberg Award for sheltering Jews during World War II. His last concert took place in the NHK Hall in Osaka on 19 September 2018.[20] He died on 1 October 2018.

Early life and family

Aznavour was born at the clinic Tarnier at 89, rue d'Assas in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, 6th arrondissement of Paris, into a family of artists living on rue Monsieur-le-Prince.[21] He was named Shahnour (or Chahnour)[2] Vaghinag (Vaghenagh)[3] Aznavourian[1] (Armenian: Շահնուր Վաղինակ Ազնավուրեան), by his parents, Armenian immigrants Michael Aznavourian (from Akhaltsikhe, Georgia)[1][22] and Knar Baghdasarian, an Armenian from Adapazari (present-day Sakarya, Turkey).[23][24] His father sang in restaurants in France before establishing a Caucasian restaurant called Le Caucase. Charles's parents introduced him to performing at an early age, and he dropped out of school at age nine, and took the stage name "Aznavour".[25]

World War II

During the German occupation of France during World War II, Aznavour and his family hid “a number of people who were persecuted by the Nazis, while Charles and his sister Aida were involved in rescue activities.” Their work was recognized in a statement issued in 2017 by Reuven Rivlin, President of Israel. That year, Aznavour and Aida received the Raoul Wallenberg Award for their wartime activities. "The Aznavours were closely linked to the Missak Manouchian Resistance Group and in this context they offered shelter to Armenians, Jews and others at their own Paris flat, risking their own lives."[26][27]

Career

Musical career

Aznavour was already familiar with performing on stage by the time he began his career as a musician. At the age of nine, he had roles in a play called Un Petit Diable à Paris and a film entitled La Guerre des Gosses.[28] Aznavour then turned to professional dancing and performed in several nightclubs. In 1944, he and actor Pierre Roche began a partnership and in collaborative efforts performed in numerous nightclubs. It was through this partnership that Aznavour began to write songs and sing. The partnership's first successes were in Canada in 1948-1950. Meanwhile, Aznavour wrote his first song entitled J'ai Bu in 1950.[28]

During the early stages of his career, Aznavour opened for Edith Piaf at the Moulin Rouge. Piaf then advised him to pursue a career in singing. Piaf helped Aznavour develop a distinctive voice that stimulated the best of his abilities.[28]

Sometimes described as "France's Frank Sinatra",[13] Aznavour sang frequently about love. He wrote or co-wrote musicals, more than one thousand songs, and recorded ninety-one studio albums. Aznavour's voice was shaded towards the tenor range, but possessed the low range and coloration more typical of a baritone, contributing to his unique sound. Aznavour spoke and sang in many languages (French, English, Italian, Spanish, German, Russian, Armenian, Neapolitan and Kabyle), which helped him perform at Carnegie Hall, in the US, and other major venues around the world. He also recorded at least one song from the 18th-century Armenian poet Sayat-Nova, and a popular song, Im Yare[29] in Armenian. "Que C'est Triste Venise", sung in French, Italian ("Com'è Triste Venezia"), Spanish ("Venecia Sin Ti"), English ("How Sad Venice Can Be") and German ("Venedig in Grau"), was very successful the mid 1960s.[30]

1972 saw the release of his 23rd studio album, "Idiote je t'aime...", which contained among others, two of his classics - Les plaisirs démodés (Old-Fashioned Pleasures) et Comme ils disent (As They Say), the latter dealing with homosexuality, which at the time, was revolutionary.

In 1974, Aznavour became a major success in the United Kingdom when his song "She" was number 1 on the UK Singles Chart for four weeks during a fourteen-week run. His other well-known song in the UK was the 1973 "The Old Fashioned Way", which was on UK charts for 15 weeks.[31][32][33][34]

Artists who have recorded his songs and collaborated with Aznavour include Édith Piaf, Fred Astaire, Frank Sinatra (Aznavour was one of the rare European singers invited to duet with him[35]), Andrea Bocelli, Bing Crosby, Ray Charles, Bob Dylan (he named Aznavour among the greatest live performers he had ever seen),[36][37] Dusty Springfield, Liza Minnelli, Mia Martini, Elton John, Dalida, Serge Gainsbourg, Josh Groban, Petula Clark, Tom Jones, Shirley Bassey, José Carreras, Laura Pausini, Roy Clark, Nana Mouskouri and Julio Iglesias. Fellow French pop singer Mireille Mathieu sang and recorded with Aznavour on numerous occasions. The English singer Marc Almond was noted by Aznavour as his favourite interpreter of his songs, having covered Aznavour's "What makes a man a man" in the 1990s. Almond citing Aznavour as a major influence on his style and work. In 1974, Jack Jones recorded an entire album of Aznavour compositions entitled Write Me A Love Song, Charlie, re-released on CD in 2006.[38][39] Two years later, in 1976, Dutch singer Liesbeth List released her album Charles Aznavour Presents Liesbeth List, which featured Aznavour's compositions with English lyrics. Aznavour and Italian tenor Luciano Pavarotti sang Gounod's aria "Ave Maria" together. He performed with Russian cellist and friend Mstislav Rostropovich to inaugurate the French presidency of the European Union in 1995. Elvis Costello recorded "She" for the film Notting Hill. One of Aznavour's greatest friends and collaborators from the music industry was Spanish operatic tenor Plácido Domingo, who often performs his hits, most notably a solo studio recording of "Les bâteaux sont partis" in 1985 and duet versions of the song in French and Spanish in 2008, as well as multiple live renditions of Aznavour's "Ave Maria". In 1994, Aznavour performed with Domingo again and Norwegian soprano Sissel Kyrkjebø at Domingo's third annual Christmas in Vienna concert. The three singers performed a variety of carols, medleys and duets, and the concert was televised throughout the world, as well as released on a CD internationally.[40]

At the start of autumn 2006, Aznavour initiated his farewell tour, performing in the US and Canada, and earning very positive reviews. Aznavour started 2007 with concerts all over Japan and Asia. The second half of 2007 saw Aznavour return to Paris for over 20 shows at the Palais des Congrès in Paris, followed by more touring in Belgium, the Netherlands, and the rest of France. Aznavour had repeatedly stated that this farewell tour, health permitting, would likely last beyond 2010; after that, however, Charles Aznavour continued performing worldwide throughout the year. At 84, 60 years on stage made him "a little hard of hearing".[41] In his final years he would still sing in multiple languages and without persistent use of teleprompters, but typically he would stick to just two or three (French and English being the primary two, with Spanish or Italian being the third) during most concerts.[42] On 30 September 2006, Aznavour performed a major concert in Yerevan, the capital of Armenia, to start off the cultural season "Arménie mon amie". Then Armenian president Robert Kocharyan and his French counterpart Jacques Chirac, at the time on an official visit to Armenia, were in front-row attendance.[43]

In 2006, Aznavour recorded his album Colore ma vie in Cuba, with Chucho Valdés.[44] A regular guest vocalist on Star Academy, Aznavour sang alongside contestant Cyril Cinélu that same year.[45] In 2007, he sang part of "Une vie d'amour" in Russian during a Moscow concert.[46] Later, in July 2007, Aznavour was invited to perform at the Vieilles Charrues Festival.[47]

Forever Cool (2007), an album from Capitol/EMI, features Aznavour singing a new duet of "Everybody Loves Somebody Sometime" with the voice of Dean Martin.[48]

Aznavour finished a tour of Portugal in February 2008.[49] Throughout the spring of 2008, Aznavour toured South America, holding a multitude of concerts in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Uruguay.[50]

An admirer of Quebec, where he played in Montreal cabarets before becoming famous, he helped the career of Québécoise singer-lyricist Lynda Lemay in France, and had a house in Montreal. On 5 July 2008, he was invested as an honorary officer of the Order of Canada. He performed the following day on the Plains of Abraham as a feature of the celebration of the 400th anniversary of the founding of Quebec City.[51]

In 2008, an album of duets, Duos, was released. It is a collaborative effort featuring Aznavour and his greatest friends and partners from his long career in the music industry, including Céline Dion, Sting, Laura Pausini, Josh Groban, Paul Anka, Plácido Domingo and many others.[52] It was released on various dates in December 2008 across the world.[53] His next album, Charles Aznavour and The Clayton Hamilton Jazz Orchestra (previously known as Jazznavour 2), is a continuation in the same vein as his hit album Jazznavour released in 1998, involving new arrangements on his classic songs with a jazz orchestra and other guest jazz artists. It was released on 27 November 2009.[54]

Aznavour and Senegalese singer Youssou N'Dour, with the collaboration of over 40 French singers and musicians, recorded a music video with the music group Band Aid in the aftermath of the catastrophic 2010 Haiti earthquake, titled 1 geste pour Haïti chérie.[55]

In 2009, Aznavour also toured across America. The tour, named Aznavour en liberté,[56] started in late April 2009 with a wave of concerts across the United States and Canada, took him across Latin America in the autumn, as well as the USA once again. In August 2011 Aznavour released a new album, Aznavour Toujours, featuring 11 new songs, and Elle, a French re-working of his greatest international hit, "She". Following the release of Aznavour Toujours, then 87-year-old Aznavour began a tour across France and Europe, named Charles Aznavour en Toute Intimité, which started with 21 concerts in the Olympia theatre in Paris.[57] On 12 December 2011, he gave a concert in Moscow State Kremlin Palace that attracted a capacity crowd.[58] The concert was followed by a standing ovation which continued for about fifteen minutes.[59]

In 2012, Aznavour embarked on a new North American leg of his En toute intimité tour, visiting Quebec and the Gibson Amphitheatre in Los Angeles, the third-largest such venue in California, for multiple shows. However, the shows in New York were cancelled following a contract dispute.[60] On 16 August 2012, Aznavour performed in his father's birthplace, Akhaltsikhe, in Georgia in a special concert as part of the opening ceremony of the recently restored Rabati castle.[61]

On 25 October 2013, Aznavour performed in London for the first time in 25 years at the Royal Albert Hall; demand was so high that a second concert at the Royal Albert Hall was scheduled for June 2014.[62] In November 2013, Aznavour appeared with Achinoam Nini (Noa) in a concert, dedicated to peace, at the Nokia Arena in Tel Aviv.[63] The audience, including Israeli president Shimon Peres (Peres and Aznavour had a meeting prior to the performance), sang along.[64] In December 2013, Aznavour gave two concerts in the Netherlands at the Heineken Music Hall in Amsterdam, and again in January 2016 (originally scheduled for November 2015, but postponed due to him suffering a brief bout of stomach flu).[65]

In 2014, 2015 and 2016, Aznavour continued his international tour, including concerts in Brussels, Berlin, Frankfurt, Barcelona, Madrid, Warsaw, Prague, Moscow, Bucharest, Antwerp, London, Dubai, Montreal, New York, Boston, Miami, Los Angeles, Osaka, Tokyo, Lisbon, Marbella, Monaco, Verona, Amsterdam and Paris.

In 2017 and 2018, his tour continued in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Santiago, Buenos Aires, Moscow, Vienna, Perth, Sydney, Melbourne and Haiti, Tokyo, Osaka, Madrid, Milan, Rome, Saint Petersburg, Paris, London, Amsterdam and Monaco. On 19 September 2018, what was to be his last concert took place in the NHK Hall of Osaka.[66]

Film appearances

See: Filmography

Aznavour also had a long and varied parallel career as an actor, appearing in over 80 films and TV movies. In 1960, Aznavour starred in François Truffaut's Tirez sur le pianiste, playing a character called Édouard Saroyan, a café pianist. He also put in a critically acclaimed performance in the 1974 movie And Then There Were None. Aznavour had an important supporting role in 1979's The Tin Drum, winner of the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1980. He co-starred in Claude Chabrol's Les Fantômes du chapelier from 1982. In the 1984 version of Die Fledermaus, he appears and performs as one of Prince Orlovsky's guests. This version stars Kiri Te Kanawa and was directed by Plácido Domingo in the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden.[67] Aznavour starred in the 2002 movie Ararat, reprising his role of Edward (Édouard) Saroyan.

Politics and activism

LGBT rights

Charles was an early supporter of LGBT rights. His 1972 album, Idiote je t'aime..., contained among others, one of his classics, "Comme ils disent" ("As They Say", the English version of which is titled "What Makes a Man"). The song, the story of a transvestite, was revolutionary at a time when talking about homosexuality was a taboo. In a later interview, Charles said “It’s a kind of sickness I have, talking about things you’re not supposed to talk about. I started with homosexuality and I wanted to break every taboo.”[68]

Armenian activism

Since the 1988 Armenian earthquake, Aznavour helped the country through his charity, Aznavour for Armenia. Together with his brother in-law and co-author Georges Garvarentz he wrote the song "Pour toi Arménie", which was performed by a group of famous French artists and topped the charts for eighteen weeks. There is a square named after him in central Yerevan on Abovian Street, and a statue erected in Gyumri, which saw the most lives lost in the earthquake. In 1995 Aznavour was appointed an Ambassador and Permanent Delegate of Armenia to UNESCO. Aznavour was a member of the Armenia Fund International Board of Trustees. The organization has rendered more than $150 million in humanitarian aid and infrastructure development assistance to Armenia since 1992. He was appointed as "Officier" (Officer) of the Légion d'honneur in 1997.[69]

In 2002, Aznavour appeared in director Atom Egoyan's acclaimed film Ararat, about the genocide of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century.[70]

In 2004, Aznavour received the title of National Hero of Armenia, Armenia's highest award. On 26 December 2008, President of Armenia Serzh Sargsyan signed a presidential decree for granting citizenship of Armenia to Aznavour whom he called a "prominent singer and public figure" and "a hero of the Armenian people".[4][71]

In 2011, the Charles Aznavour Museum opened in Yerevan.[72]

In April 2016, Aznavour visited Armenia to participate in the Aurora Prize Award ceremony. On 24 April, along with Serzh Sargsyan, the Catholicos of All Armenians, Garegin II and actor George Clooney, he laid flowers at the Armenian Genocide Memorial.[73][74]

In October 2016 Aznavour joined other prominent Armenians on calling the government of Armenia to adopt "new development strategies based on inclusiveness and collective action" and to create "an opportunity for the Armenian world to pivot toward a future of prosperity, to transform the post-Soviet Armenian Republic into a vibrant, modern, secure, peaceful and progressive homeland for a global nation."[75]

Along with holding the mostly ceremonial title of French ambassador-at-large to Armenia, Aznavour agreed to hold the position of Ambassador of Armenia to Switzerland on 12 February 2009:

First I hesitated, as it is not an easy task. Then I thought that what is important for Armenia is important for us. I have accepted the proposal with love, happiness and feeling of deep dignity[76]

He wrote a song about the Armenian Genocide, entitled "Ils sont tombés" (known in English as "They fell").[77]

Political involvement

—Herbert Kretzmer, Aznavour's long-time English lyric writer, 2014[78]

Aznavour was increasingly involved in French, Armenian and international politics as his career progressed. During the 2002 French presidential elections, when far-right nationalist Jean-Marie Le Pen of the National Front made it into the runoff election, facing incumbent Jacques Chirac, Aznavour signed the "Vive la France" petition, and called on all French to "sing the Marseillaise" in protest.[79] Chirac, a personal friend of Aznavour's, ended up winning in a landslide, carrying over 82% of the vote.

He frequently campaigned for international copyright law reform. In November 2005 he met with then President of the European Commission José Manuel Barroso[80] on the issue of the review of term of protection for performers and producers in the EU, advocating an extension of the EU's term of protection from the current 50 years to the United States' law allowing 95 years, saying "[o]n term of protection, artists and record companies are of the same mind. Extension of term of protection would be good for European culture, positive for the European economy and would put an end the current discrimination with the U.S." He also notably butted heads with French politician Christine Boutin over her defense of a "global license" flat-fee authorization for sharing of copyrighted files over the internet, claiming that the license would eliminate creativity. In May 2009, the French Senate approved one of the strictest internet anti-piracy bills ever with a landslide 189–14 vote. Aznavour was a vocal proponent of the measure and considered it a rousing victory:

If the youth can't make a living through creative work, they will do something else and the artistic world will be dealt a blow... There will be no more songs, no more books, nothing at all. So we had to fight...[81]

Legacy

His musicality and fame abroad had a significant impact on many areas of pop culture. Aznavour's name inspired the name of the character Char Aznable by Yoshiyuki Tomino in his 1979 mecha anime series Mobile Suit Gundam. His song "Parce Que Tu Crois" was sampled by producer Dr. Dre for the song "What's the Difference" (featuring Eminem & Xzibit), from his album 2001.[82] He was mentioned in The Psychedelic Furs song "Sister Europe" ("The radio upon the floor / is stupid, it plays Aznavour"), the Kemal Monteno song "Stavi tiho Aznavoura" ("Play Aznavour quietly") and the Jonathan Richman song "Give Paris One More Chance."

"I like Charles Aznavour a lot," said Bob Dylan. "I saw him in sixty-something at Carnegie Hall, and he just blew my brains out."[83]

In August 2017, at age 93, he was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[84]

In 1990, he offered insights into his life to writer-director Michael Feeney Callan in the TV series My Riviera,[85] which was filmed at and around Aznavour's home in Port Grimaud, in the South of France.

Personal life

Aznavour was married three times: to Micheline Rugel (in 1946),[86] Evelyn Plessis (in 1956) and his widow, Ulla Thorsell (in 1967). Five children were produced by these marriages: Seda, Patrick, Katia, Mischa, and Nicolas.[87][88] A sixth child, Charles Jr., supposedly born in 1952, was invented by Yves Salgues, who was Aznavour's first official biographer, but also a heroin addict.

Aznavour often joked about his physique, the most talked-about aspect of which was his height; he stood 160 cm (5 ft 3 in) tall. He made this a source of self-deprecating humour over the years.[28]

In April 2018, shortly before his 94th birthday, Aznavour was taken to hospital in Saint Petersburg after straining his back during a rehearsal prior to a concert in the city. The concert was postponed until the following season, but eventually cancelled since he died six months later.[89] On 5 May 2018, he was a guest on BBC Radio 2's Graham Norton.[90]

A week later, on 12 May, he broke his arm in two places in a fall at his home in the village of Mouriès, resulting in the cancellation of all shows until the end of June. This was eventually extended to include the 18 shows scheduled for August, because of a longer healing process.[91] In a program on French television broadcast on 28 September, only three days before his death, he mentioned that he was still feeling the pain.[92]

Death and funeral

On 1 October 2018, Aznavour was found dead in a bathtub at his home at Mouriès at the age of 94.[93][94][95][96][97] At the time of his death his tax residence was in Saint-Sulpice, Vaud, Switzerland.[98] The autopsy report concluded that Aznavour died of cardiorespiratory arrest complicated by an acute pulmonary edema.[93] A requiem mass for him was held on October 6 by Catholicos Karekin II at the Armenian Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Paris.[99]

On 5 October, Aznavour was honoured with a state funeral at Les Invalides military complex in Paris, with president Emmanuel Macron lauding him as one of the most important “faces of France”. He praised Aznavour's lyrics, which he said appealed to "our secret fragility" and said the singer's words were "for millions of people a balm, a remedy, a comfort ... For so many decades, he has made our life sweeter, our tears less bitter." His coffin was lifted away at the end to the sound of his hit song "Emmenez-Moi" (Take Me Along).[100] Dignitaries attending the funeral also included French Prime Minister Édouard Philippe, former presidents Nicolas Sarkozy and François Hollande, as well as Armenian President Armen Sarkissian and Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and their wives.[101]

He is buried in the family crypt at the Montfort-l'Amaury cemetery.[102]

Awards and recognition

Honours

- 1995 – Grand Medal of the French Academy[103]

- 1997 – Officier (Officer) of the Legion of Honour[104]

- 2004 – Commandeur (Commander) of the Legion of Honour[105]

- 2004 – National Hero of Armenia[106]

- 2004 – Officer of the Order of Leopold[107]

- 2008 – Honorary Officer of the Order of Canada[108]

- 2008 – Citizenship of Armenia[4]

- 2009 – Officer of the National Order of Quebec[109]

- 2015 – Commander in the Belgian Order of the Crown[110]

- 2017 – Raoul Wallenberg Medal[26]

- 2018 - Order of the Rising Sun

Awards

- 1963, 1971, and 1980 – Edison Awards (three-time award winner)[111]

- 1971 – Golden Lion Honorary Award at the Venice Film Festival for the Italian version of the song Mourir d'aimer[112]

- 1995 – Ambassador of Goodwill and Permanent Delegate of Armenia to UNESCO[113]

- 1996 – Induction into the Songwriters Hall of Fame[114]

- 1997 – French Victoire award for Male Artist of the Year[115]

- 1997 – Honorary César Award[116]

- 2009 – MIDEM Lifetime Achievement Award[117]

- 2009 – Grigor Lusavorich award of Nagorno-Karabakh Republic[118]

- 2009 – Honorary Doctorate from the University of Montreal[119]

- 2010 – Honorary order from Russia "For contributing to strengthening cultural relations between Russia and France"[120]

- 2014 – Special Prize named after Rouben Mamoulian of the "Hayak" National Film Awards in Armenia for "his great contribution to world cinema"[121]

- 2016 – Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for Live Performance, located at 6225 Hollywood Boulevard[122]

Bibliography

- Aznavour par Aznavour, Paris, Fayard, 1970, 311 p. (ISBN 978-2-7020-0214-8).

- Des mots à l'affiche, Paris, Le Cherche-midi, 1991, 153 p. (ISBN 978-2-86274-210-6).

- Mes chansons préférées, (co-authored with Daniel Sciora), Christian Pirot, 2000

- Le Temps des avants, Paris, Flammarion, 2003, 354 p. (ISBN 2-08-068536-8).

- Images de ma vie (photo book), Flammarion, 2005

- Mon père, ce géant, Paris, Flammarion, 2007, 152 p. (ISBN 978-2-08-120974-9 et 2-08-120974-8)

- À voix basse, Paris, Don Quichotte, 2009, 225 p. (ISBN 978-2-35949-001-5).

- D'une porte l'autre, Paris, Éditions Don Quichotte, 2011, 163 p. (ISBN 978-2-35949-044-2)

- En haut de l'affiche, Paris, Flammarion, 2011, 150 p. (ISBN 978-2-08-125710-8)

- Tant que battra mon cœur, Paris, Éditions Don Quichotte, 2013, 228 p. (ISBN 978-2-35949-162-3)

- Ma vie, mes chansons, mes films, (co-authored with Philippe Durant & Vincent Perrot), Paris, Éditions de la Martinière, 2015, 232 p. (ISBN 978-2-7324-7083-2)

- Retiens la vie, Paris, Éditions Don Quichotte, 2017, 139 p. (ISBN 978-2-35949-683-3)

Discography

Filmography

References

- Notes

- Citations

- "Portrait de S.E. Charles Aznavour" (in French). Embassy of Armenia in Switzerland. Archived from the original on 30 June 2014.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (2007). The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. p. 215. ISBN 9781412835923.

- Katz, Ephraim (26 February 2013). The Film Encyclopedia (7th ed.). New York: HarperCollins. p. 1653. ISBN 9780062277114.

- Itzkoff, David (26 December 2008). "Aznavour Granted Armenian Citizenship". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Riding, Alan (18 October 1998). "Aznavour, The Last Chanteur". The New York Times.

...his highly distinct tenor voice ...

- Charles Aznavour recorded in French, English, Italian, Spanish, German, Armenian (Yes kou rimet'n tchim kidi, La goutte d'eau and Sirerk), Neapolitan (Napule amica mia), Russian (Vetchnai lioubov) and Kabyle (La bohème in a duet with Idir). Charles Aznavour Songs Catalog

- Cords, Suzanne (21 May 2014). "The master of the chanson". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

Long a legend, Charles Aznavour is the best known French chansonnier and arguably Armenia's most famous son.

- Shea, Michael (2006). The Freedom Years: Tactical Tips for the Trailblazer Generation. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 122. ISBN 9781841127545.

One of France's best known pop stars, Charles Aznavour ...

- Henri Margueritte (15 May 2017). "Charles Aznavour : "Chanter au Maroc est un grand moment de bonheur"". Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- "Charles Aznavour a son étoile : "Quand on m'apporte quelque chose, je suis ravi"". RTL (in French). Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "Charles Aznavour à Trélazé - À Montréal le 21 octobre > Les ArtsZé" (in French). Les ArtsZé. 30 August 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "C à vous Intégrale : Juliette Binoche, Charles Aznavour, Mireille Dumas et Raphaël Esrail" (in French). 22 September 2017. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Deming, Mark. "Charles Aznavour 40 Chansons D'or". AllMusic. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- Hunter-Tilney, Ludovic (28 October 2013). "Charles Aznavour, Royal Albert Hall, London – review". Financial Times. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- Holden, Stephen (30 April 2009). "Aznavour Exploring Both Love and l'Amour". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- Akopian, Aram (2001). Armenians and the World: Yesterday and Today. Yerevan: Noyan Tapan. p. 91. ISBN 9789993051299.

It will be probably just to say that today he is the most famous Armenian, known and admired all over the world.

- "Charles Aznavour: A chat with the legendary performer, winner of the TIME 100 Online poll as the Entertainer of the Century". TIME. 9 July 1998. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- Alexis Petridis (1 October 2018). "From drag queens to dead marriages, Charles Aznavour was far from easy listening". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- "Aznavour to become Armenian envoy". BBC. 13 February 2009.

- "Le Japon pleure la disparition de Charles Aznavour". RTL France (in French). Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Raoul Bellaïche (24 August 2014). Aznavour "Non je n'ai rien oublié" [Aznavour "No, I have not forgotten anything"] (in French). Éditions de l'Archipel. p. 11. ISBN 9782809807646. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Biographie Charles Aznavour". Musicme.com. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Biodata". Billetnet.fr. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "CHARLES AZNAVOUR - Encyclopædia Universalis". Universalis.fr. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Charles Aznavour". RFI Musique. December 2008. Archived from the original on 10 February 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- "Charles Aznavour and his sister Aida received the Raoul Wallenberg Medal". The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- "Legendary singer Aznavour given award for family efforts to save Jews in WWII". Times of Israel. AFP. 28 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- Henderson, Lol; Stacey, Lee, eds. (2014). Encyclopedia of Music in the 20th Century. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 35. ISBN 978-1135929466.

- "Charles and Seda Aznavour Record New Duo in Armenian". Armenian Weekly. 12 January 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "5 canciones para recordar a Charles Aznavour". El Periódico. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Talent in Europe / Billboard 22 January 1977, p. 36

- Songwriters: a biographical dictionary with discographies - by Nigel Harrison - 1998 - p. 28

- "Official Charts Company". www.officialcharts.com.

- "Song artist 642 - Charles Aznavour". Tsort.info. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Album review - Charles Aznavour's "Duos"". RFI Musique. 28 December 2009. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Bob Dylan interview: Rolling Stone Nov/Dec 1987". Expectingrain.com. 10 December 1995. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "Song of the Day: Bob Dylan, "The Times We've Known" (Charles Aznavour cover) » Cover Me". Covermesongs.com. 13 August 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- Archived 12 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Jack Jones (29 August 2006). "Jack Jones - Write Me a Love Song Charlie (Mini Lp Sleeve) - Amazon.com Music". Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- Aryeh Oron (October 2005). "Sissel Kyrkjebø (Soprano)". Bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "Aznavour's long goodbye – 83 and still singing". Expatica.com. 8 October 2007. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- Riding, Alan (18 September 2006). "At 82, Charles Aznavour Is Singing a Farewell That Could Last for Years". The New York Times.

There are some people who grow old and others who just add years. I have added years, but I am not yet old ...

- Biographie Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- François-Xavier Gomez (1 October 2018). "Un tropisme latino pour Aznavour". Libération (in French). Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Marie Boscher (1 October 2018). "Hommages de l'Outre-mer à Charles Aznavour, mort à 94 ans" (in French). France Info. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Yan Shenkman (22 May 2014). "Le destin russe d'Aznavour". Russia Beyond the Headlines (in French). Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Anaelle Berre (1 October 2018). "Charles Aznavour. Un rappel exceptionnel aux Vieilles Charrues 2007". Ouest-France (in French). Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "La Francia dice addio a Charles Aznavour". Giornale di Brescia (in Italian). 1 October 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "Morreu cantor e compositor Charles Aznavour". Visão (in Portuguese). 1 October 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "Aznavour llega a Chile con su último disco recién editado en español". El Mercurio (in Spanish). 6 May 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Andy Blatchford. "Aznavour receives Order of Canada honours in Quebec". Toronto: globeandmail.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- Jason Birchmeier. "Charles Aznavour – Duos". AllMusic.

- "Charles Aznavour se paie "la totale" dans son nouvel album" [Charles Aznavour pays himself "it all" in his new album] (in French). Voir.ca. 22 October 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "Charles Aznavour". RFI Music. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- "French music stars mobilise for Haiti". AFP. 15 January 2010. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "Aznavour en Liberté". Patwhite.com. 23 April 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "Charles Aznavour upcoming concerts". Songkick.com. 9 January 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "Charles Aznavour wows Moscow". The Voice of Russia. 13 December 2011. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- "Moscow impressed by Charles Aznavour (VIDEO)". News.am. 13 December 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- Schuessler, Jennifer (24 April 2012). "Charles Aznavour Cancels New York Shows in Contract Dispute". The New York Times.

- "The star of Charles Aznavour was placed in Akhaltsikhe". Armenpress. 17 August 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "Charles Aznavour — Royal Albert Hall". Royalalberthall.com. 3 November 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Noa and Charles Aznavour – She". Achinoam Nini's Official Website.

- Fay, Greer (24 November 2013). "Peres among Israeli fans attending Aznavour concert - Arts & Culture - Jerusalem Post". Jpost.com. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Ailing French Singer Charles Aznavour Cancels Concerts". newsmax.com. 24 November 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- "Search for setlists: artist:(Charles Aznavour) date:[2018-01-01 TO 2018-12-31] - setlist.fm". www.setlist.fm. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- IMDB. "Die Fledermaus".

- Angelique Chrisafis (21 June 2015). "Charles Aznavour: 'I wanted to break every taboo'". The Guardian.

- Cross, Tony (1 October 2018). "Charles Aznavour dies, aged 94". Radio France Internationale.

- Bernstein, Adam. "Charles Aznavour, daring and adored French singer and composer, dies at 94". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- "French crooner Charles Aznavour granted Armenian citizenship". France 24. 27 December 2008.

- Aznavour-Erevan Archived 18 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Charles Aznavour arrives in Armenia". 21 April 2016.

- "President, Aznavour, Clooney visit Genocide memorial".

- "'Global Armenians' Ad in NY Times Calls For 'Inclusive Leadership' in Armenia". Asbarez. 28 October 2016. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020.; text also available at "The Future for All Armenians Is Now". auroraprize.com. Aurora Prize for Awakening Humanity. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020.

- "Charles Aznavour Ambassador of Armenia to Switzerland". Panorama.am. 13 February 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- Nora Koloyan-Keuhnelian (2 October 2018). "Adieu Aznavour". Al-Ahram. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Kretzmer, Herbert (2014). "Charles Aznavour - Troubadour". Snapshots: Encounters with Twentieth-Century Legends. Biteback Publishing.

- "Biography – Charles Aznavour". Rfimusique.com. Archived from the original on 16 April 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "Charles Aznavour meets EC President José Manuel Barroso". Ifpi.org. 1 September 2005. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "French bill to combat Internet piracy clears final hurdle". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 May 2009.

- "Dr DRE, What's the difference". Samples.fr. 27 March 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- Rolling Stone, 1987 (precise issue and date unknown)

- "French singer Charles Aznavour gets Hollywood star at age of 93". The Daily Telegraph. 25 August 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018 – via Reuters News.

- "My Riviera". IMDb.com. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- "Biography for Charles Aznavour". imdb.com. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- "Biographie de Charles AZNAVOUR". leParisien.fr. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- "Charles Aznavour : qui sont ses six enfants, Seda, Charles, Patrick, Katia, Mischa et Nicolas ?". Femme Actuelle. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Charles Aznavour Hospitalized in St. Petersburg – Asbarez.com". asbarez.com. 25 April 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "With Pam Ayres, Charles Aznavour, plus Rylan Clark-Neal and Scott Mills, Graham Norton – BBC Radio 2". BBC. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- "Charles Aznavour cancels more appearances due to broken arm". hollywood.com. 18 June 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "Aznavour: le monument français! – C à Vous – 28/09/2018". YouTube. 28 September 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "Mort de Charles Aznavour : "La cause de la mort est naturelle"". FranceTV (in French). 2 October 2018.

- "Charles Aznavour est décédé à l'âge de 94 ans". RTL France (in French). 1 October 2018.

- "Le chanteur Charles Aznavour est décédé". Le Dauphiné libéré (in French). 1 October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- "Singer Charles Aznavour dies at 94". BBC News. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018 – via BBC.

- "Charles Aznavour, Enduring French Singer of Global Fame, Dies at 94". The New York Times. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- Marion Moussadek (12 November 2013). "Aznavour: "J'ai été poussé à vivre en Suisse"". Le Matin (in French). Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- "PM Pashinyan attends requiem ceremony offered for Charles Aznavour at St. John the Baptist Church in Paris". Armenpress. 6 October 2018.

- Angelique Chrisafis (5 October 2018). "'In France, poets never die': Macron pays tribute to Aznavour 'Son of immigrants' likened to Apollinaire and praised for his cultural contribution to France". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Brian Love (5 October 2018). "France bids adieu to Aznavour, pays tribute to Armenian roots". Reuters. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Du monde à Montfort l'Amaury pour se recueillir sur la tombe de Charles Aznavour, France Bleu (in French). 3 November 2018.

- "5 dates clés dans la carrière de Charles Aznavour" (in French). Nostalgie. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "France/Légion d'honneur : la promotion du Nouvel An ŕ de nombreuses personnalités de divers milieux" (in French). French.peopledaily.com.cn. 2 January 2004. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Aznavour commandeur

de la Légion d'honneur". O (in French). Retrieved 20 January 2018. - "Charles Aznavour and Kirk Kerkorian National Heroes of Armenia". Panarmenian.net. 28 May 2004. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "Les liens particuliers de Charles Aznavour avec la Belgique". La Libre (in French). 1 October 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "Aznavour receives Order of Canada honours in Quebec - The Globe and Mail". The Globe and Mail. 31 March 2009. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Citation". National Order of Quebec.

- "Charles Aznavour fait commandeur de l'Ordre de la couronne". RTBF (in French). 16 November 2015.

- Lumley, Elizabeth, ed. (2009). Canadian Who's Who 2009. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0802040923.

- Colonna-Césari, Annick (19 July 2015). "Mourir d'aimer: Charles Aznavour contre le conservatisme des années 1970". L'Express. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "Delegation of Armenia to UNESCO". Erc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 11 October 2003. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- Gregory Viscusi (1 October 2018). "Charles Aznavour, French Singer Compared to Sinatra, Dies at 94". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "Les grandes dates de la vie de Charles Aznavour". Le Point. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "French singer, actor Charles Aznavour dies at age 94". CBS. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "Aznavour to receive MIDEM award, PanArmenian.net, 15.01.2009". Panarmenian.net. 15 January 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "Именем Шарля Азнавура в Степанакерте назван культурный центр, Regnum, 2009". Regnum.ru. 18 May 2009. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- "Charles Aznavour, who had lifelong love affair with Quebec, has died". Montreal Gazette. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "Charles Aznavour receives Russian award". The Voice of Russia. 25 August 2010.

- "The French-Armenian legendary singer Charles Aznavour was awarded with the special prize named after Ruben Mamulyan during". Armenpress. 13 May 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- "French crooner Charles Aznavour gets honorary Hollywood Star plaque". Reuters. 29 October 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Aznavour. |

- Official website

- Aznavour Foundation

- Charles Aznavour on imusic.am

- "Portrait de S.E. Charles Aznavour" (in French). Embassy of Armenia in Switzerland. Archived from the original on 30 June 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- Charles Aznavour on IMDb

- Charles Aznavour at the Songwriters Hall of Fame

- Biography by Radio France International

- Charles Aznavour – Armenian-Russian Pages

| Awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Maxime Le Forestier |

Male artist of the year at the Victoires de la Musique 1997 |

Succeeded by Florent Pagny |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by Zohrab Mnatsakanian |

Permanent Representative of Armenia to the United Nations in Geneva from 26 June 2009 till 1 October 2018 |

Incumbent |

| Ambassador of Armenia to Switzerland from 30 June 2009 till 1 October 2018 | ||