Serge Gainsbourg

Serge Gainsbourg (French pronunciation: [sɛʁʒ ɡɛ̃sbuʁ];[4] born Lucien Ginsburg;[5] 2 April 1928 – 2 March 1991)[1] was a French singer, songwriter, pianist, film composer, poet, painter, screenwriter, writer, actor and director.[6] Regarded as the most important figure in French pop whilst alive, he was renowned for often provocative and scandalous releases which caused uproar in France, dividing its public opinion;[7][8] as well as his diverse artistic output, which ranged from his early work in jazz, chanson, and yé-yé to later efforts in rock, funk, reggae, and electronica.[9] Gainsbourg's varied musical style and individuality make him difficult to categorize, although his legacy has been firmly established and he is often regarded as one of the world's most influential popular musicians.[10]

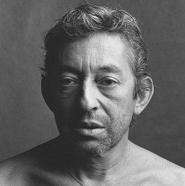

Serge Gainsbourg | |

|---|---|

Gainsbourg in 1981 | |

| Born | Lucien Ginsburg 2 April 1928 Paris, France |

| Died | 2 March 1991 (aged 62) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Other names |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1957–1991 |

| Spouse(s) | Elisabeth "Lize" Levitsky

( m. 1951; div. 1957)Béatrice Pancrazzi

( m. 1964; div. 1966) |

| Partner(s) |

|

| Children | 4, including Charlotte Gainsbourg |

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | (Universal Music Group) |

| Associated acts | Charlotte Gainsbourg |

| Website | Official website from Universalmusic |

His lyrical works incorporated wordplay, with humorous, bizarre, provocative, sexual, satirical or subversive overtones, including sophisticated rhymes, mondegreen, onomatopoeia, spoonerism, dysphemism, paraprosdokian and pun. Gainsbourg wrote over 550 songs,[11][12] which have been covered more than 1,000 times by a range of artists.[13] Since his death from a second heart attack in 1991, Gainsbourg's music has reached legendary stature in France, and he is regarded as France's greatest ever musician and one of the country's most popular and endeared public figures.[14] He has also gained a cult following in the English-speaking world with chart success in the United Kingdom and the United States with "Je t'aime... moi non-plus" and "Bonnie and Clyde", respectively.

Biography

Born in Paris, France, Gainsbourg was the son of Jewish Russian migrants, Joseph Ginsburg (28 December 1898, in Kharkov, Russian Empire now Ukraine—22 April 1971) and Olga[15] (née Bessman; 1894 – 16 March 1985), who fled to Paris after the 1917 Russian Revolution.[16][17] Joseph Ginsburg was a classically trained musician whose profession was playing the piano in cabarets and casinos; he taught his children—Gainsbourg and his twin sister Liliane—to play the piano.[18][19][20]

Gainsbourg's childhood was profoundly affected by the occupation of France by Germany during World War II. The identifying yellow star that Jews were required to wear haunted Gainsbourg; in later years he was able to transmute this memory into creative inspiration. During the occupation, the Jewish Ginsburg family was able to make their way from Paris to Limoges, traveling under false papers. Limoges was in the Zone libre under the administration of the collaborationist Vichy government and still a perilous refuge for Jews. After the war, Gainsbourg obtained work teaching music and drawing in a school outside of Paris, in Le Mesnil-le-Roi. The school was set up under the auspices of local rabbis, for the orphaned children of murdered deportees. Here Gainsbourg heard the accounts of Nazi persecution and genocide, stories that resonated for Gainsbourg far into the future.[21] Before he was 30 years old, Gainsbourg was a disillusioned painter but earned his living as a piano player in bars.[22]

Gainsbourg changed his first name to Serge, feeling that this was representative of his Russian background and because, as Jane Birkin relates: "Lucien reminded him of a hairdresser's assistant."[23] He chose Gainsbourg as his last name, in homage to the English painter Thomas Gainsborough, whom he admired.[24]

He married Elisabeth "Lize" Levitsky on 3 November 1951 and divorced in 1957. He married a second time on 7 January 1964, to Françoise-Antoinette "Béatrice" Pancrazzi (b. 28 July 1931), with whom he had two children: a daughter named Natacha (b. 8 August 1964) and a son, Paul (born in spring 1968). He divorced Béatrice in February 1966.

In late 1967 he had a brief but ardent love affair with Brigitte Bardot, to whom he dedicated the song and album Initials B.B.. He initially composed the song Je t'aime... moi non plus as a duet with her, but Bardot, married at the time, pleaded with Gainsbourg not to release it.

In mid-1968 Gainsbourg fell in love with the younger English singer and actress Jane Birkin, whom he met during the shooting of the film Slogan. Their relationship lasted over a decade.[25] In 1971 they had a daughter, the actress and singer Charlotte Gainsbourg. Although many sources state that they were married,[26] according to their daughter Charlotte this was not the case.[25] Birkin left Gainsbourg in 1980.

Birkin remembers the beginning of her affair with Gainsbourg: he first took her to a nightclub, then to a transvestite club, and afterward to the Hilton hotel where he passed out in a drunken stupor. She left him when pregnant with her third daughter Lou by the film director Jacques Doillon.

His last official partner was Bambou. In 1986, they had a son, Lucien, known as Lulu.[1] In 2010, Lise Lévitzky published a book called Lise et Lulu which raises the possibility of Gainsbourg being bisexual.[27][28] In 2017, Constance Meyer published a book called La jeune fille et Gainsbourg, in which she reveals that she had a love affair with the musician during his last years, which began in 1985 when, then aged 16, she sent him a love letter.[29]

Early work

His early songs were influenced by Boris Vian and were largely in the vein of old-fashioned chanson.

Around 1958 he backed the Parisian "Cabaret Milord l'Arsouille" star, singer Michèle Arnaud. She discovered a shy songwriter, who considered his compositions too modern and provocative for mainstream chanson. Arnaud offered to sing and even record such songs, and propelled his early career.

Later, Gainsbourg began to move beyond this and experiment with a succession of musical styles: modern jazz early on, yé-yé pop in the 1960s, then funk, rock and reggae in the 1970s and electronica in the 1980s.[9]

Many of his songs contained themes with a bizarre, morbid or sexual twist in them. An early success, "Le Poinçonneur des Lilas", describes the day in the life of a Paris Métro ticket man, whose job is to stamp holes in passengers' tickets. Gainsbourg describes this chore as so monotonous, that the man eventually thinks of putting a hole into his own head and being buried in another.

By the time the yéyés emerged in France, Gainsbourg was 32 years old and was not feeling very comfortable: he spent much time with Jacques Brel or Juliette Gréco but the public and critics rejected him, mocking his prominent ears and nose. During this period, Gainsbourg began working with Gréco, a collaboration that lasted throughout the 'Left Bank' period culminating in the song La Javanaise in the fall of 1962.

He performed a few duets in 1964 with the artist Philippe Clay, with whom he shared some resemblance. Around this time, Gainsbourg met Elek Bacsik, who pleased Gainsbourg, despite knowing that such a sound would not allow him access to success. The album Gainsbourg Confidentiel sold only 1,500 copies. The decision was taken right upon leaving the studio: "I'll get into hack work and buy myself a Rolls". Still, his next album, Gainsbourg Percussions, inspired by the rhythms and melodies of Miriam Makeba and Babatunde Olatunji, was a world away from the yéyé wave, on the scene which was to become a key to the Gainsbourg fortune.

More success began to arrive when, in 1965, his song Poupée de cire, poupée de son was the Luxembourg entry in the Eurovision Song Contest. Performed by French teen and charming singer France Gall, it won first prize. The song was recorded in English as "A Lonely Singing Doll" by British teen idol Twinkle.[1]

His next song for Gall, Les Sucettes ("Lollipops"), caused a scandal in France: Gainsbourg had written the song with double meanings and strong sexual innuendo, of which the singer was apparently unaware when she recorded it. Whereas Gall thought that the song was about a girl enjoying lollipops, it was actually about oral sex. The controversy arising from the song, although a big hit for Gall, threw her career off-track in France for several years.

Gainsbourg arranged other Gall songs and LPs that were characteristic of the late 1960s psychedelic styles, among them her 1968 album. Another Gainsbourg song, Boum Bada Boum, was entered by Monaco in the 1967 contest, sung by Minouche Barelli; it came fifth. He also wrote hit songs for other artists, such as Françoise Hardy (Comment te dire adieu, based on a complex scheme of rare rhymes), Anna Karina (Sous le soleil exactement, Ne dis rien), and his lifelong friend and muse-égérie, Michèle Arnaud (Les Papillons Noirs).[1]

In 1967, Gainsbourg appeared as a dancer along with Jean Yanne and Sacha Distel in the Sacha Show with Marie Laforet singing Ivan, Boris & Moi.

His relationship with Brigitte Bardot led to a series of prominent pop duets, such as Ford Mustang and Bonnie and Clyde.

In 1969, he released Je t'aime... moi non-plus, which featured explicit lyrics and simulated sounds of female orgasm. The song appeared that year on an LP, Jane Birkin/Serge Gainsbourg. Originally recorded with Brigitte Bardot, it was released with his future girlfriend Birkin when Bardot backed out. While Gainsbourg declared it the "ultimate love song", it was considered too "hot"; the song was censored or banned from public broadcast in numerous countries and in France even the toned-down version was suppressed. The Vatican made a public statement citing the song as offensive. Despite (or perhaps because of) the controversy, it sold well and charted within the top ten in many European countries.

The 1970s

Histoire de Melody Nelson was released in 1971. This concept album, produced and arranged by Jean-Claude Vannier, tells the story of a Lolita-esque affair, with Gainsbourg as the narrator. It features prominent string arrangements and even a massed choir at its tragic climax. The album has proven influential with artists such as Air, David Holmes, Jarvis Cocker, Beck and Dan the Automator.[30]

He had a heart attack in May 1973, but refused to cut back on smoking and drinking.[31]

In 1975, he released the album Rock Around the Bunker, an album written entirely on the subject of National Socialism. Gainsbourg used black comedy, as he and his family had suffered during World War II, being forced to wear the yellow star as the mark of a Jew. Rock Around the Bunker belonged to the mid-1970s "retro" trend.

The next year saw the release of another major work, L'Homme à tête de chou (Cabbage-Head Man), featuring the new character Marilou and sumptuous orchestral themes. Cabbage-Head Man is one of his nicknames, as it refers to his ears. Musically, L'homme à tête de chou turned out to be Gainsbourg's last LP in the English rock style he had favoured since the late 1960s. He would go on to produce two reggae albums recorded in Jamaica (1979 and 1981) and two electronic funk albums recorded in New York (1984 and 1987).

In Jamaica in 1979, he recorded "Aux Armes et cætera", a reggae version of the French national anthem "La Marseillaise", with Robbie Shakespeare, Sly Dunbar and Rita Marley. Following harsh and anti-semitic criticism in right-wing newspaper Le Figaro by Charles de Gaulle biographer Michel Droit, his song earned him death threats from right-wing veteran soldiers of the Algerian War of Independence, who were opposed to their national anthem being arranged in reggae style. In 1979, a show had to be cancelled, because an angry mob of French Army parachutists came to demonstrate in the audience. Alone onstage, Gainsbourg raised his fist and answered: "The true meaning of our national anthem is revolutionary" and sang it a capella with the audience. The soldiers joined them, a scene enjoyed by millions as French TV news broadcast it, creating more publicity. Shortly afterward, Gainsbourg purchased the original manuscript of "La Marseillaise". He replied to his critics that his version was closer to the original as the manuscript actually features the words "Aux armes et cætera..." for the chorus. This album, described by legendary drummer Sly Dunbar as "Perhaps the best record he ever played on", was his biggest commercial success, including major hits Lola Rastaquouère, Aux armes et cætera and a French version of Sam Theard's jazz classic You Rascal You entitled Vieille canaille.[32] Rita Marley and the I-Three would record another controversial reggae album with him in 1981, Mauvaises nouvelles des étoiles. Bob Marley was furious, when he discovered that Gainsbourg made his wife Rita sing erotic lyrics.[33] Posthumous new mixes, including dub versions by Soljie Hamilton and versions of both albums by Jamaican artists, were released as double "Dub Style" albums in 2003, to critical praise in France as well as abroad and to international commercial success. Although belatedly, Aux Armes Et Cætera – Dub Style and Mauvaises Nouvelles Des Étoiles – Dub Style further established Gainsbourg, posthumously, as an influential icon in European pop music.

Final years

In 1982, Gainsbourg wrote an album for French rocker Alain Bashung, Play blessures. The album, although now considered a masterpiece by French critics, was a commercial failure.[34]

After a turbulent 13-year relationship, Jane Birkin left Gainsbourg.[11] He still went on to write and produce three more albums for her: Baby Alone in Babylone (1983), Lost Song (1987), Amour des feintes (1990), with many songs being about their relationship (including Fuir le bonheur de peur qu'il ne se sauve, which would be read by Catherine Deneuve during Gainsbourg funerals in 1991).

In the 1980s, near the end of his life, Gainsbourg became a regular figure on French TV. His appearances were increasingly devoted to his controversial sense of humour and provocation. In March 1984, he burned three-quarters of a 500-French-franc bill on television to protest against taxes rising up to 74% of income.[35][36]

He would show up drunk and unshaven on stage: in April 1986, on Michel Drucker's live Saturday evening television show Champs-Élysées, with the American singer Whitney Houston, he objected to Drucker's translating his comments to Whitney Houston and in English stated: "I said, I want to fuck her"—Drucker, utterly embarrassed, insisted that this meant "He says you are great..."[33] That same year, in another talk show interview, he appeared alongside Catherine Ringer, the well-known singer from Les Rita Mitsouko who had appeared in pornographic films. Gainsbourg spat out at her, "You're nothing but a filthy whore".[37]

For many in France, this incident was the last straw, and much of his later work was overlooked since it was often done and performed while he was inebriated. After Gainsbourg's passing, Eddy Mitchell reported that their duet of "You Rascal You" had far fewer sales than would have normally been expected because of this. Michel Drucker, also, reported that he had a difficult time apologizing to Whitney Houston. After that particular incident, Gainsbourg was never again really "clean" in public, almost always having a drink in his hand and a lit cigarette between his lips, thus disgusting many with his behavior and demeanor in all he said and did. Famous humorist Pierre Desproges, who commented the incident with Catherine Ringer, said that he had admired Gainsbourg when he was alive (meaning to say that he was currently as good as dead), and that he was "the only genius looking like a garbage can" ("le seul génie qui ressemble à une poubelle").

His songs became increasingly eccentric during this period, ranging from the anti-drug Aux Enfants de la Chance, to the highly controversial duet with his daughter Charlotte named Lemon Incest.[38] This translates as "Inceste de citron", a wordplay on "un zeste de citron" (a lemon zest). The title demonstrates Gainsbourg's love for silly and sometimes outrageous puns – another example of which is Beau oui comme Bowie, a song he gave to Isabelle Adjani.

Yet he continued to produce albums and songs for women—typically women with a frail voice—some of them highly successful, like the aforementioned Baby Alone in Babylone (1983) and Amour des feintes (1987) for Jane Birkin, Variations sur le même t'aime (1990) for Vanessa Paradis, Pull marine (1983) for Isabelle Adjani, White and Black Blues for Joëlle Ursull (which came second at the 1990 Eurovision).

In December 1988, while a judge at a film festival in Val d'Isère, he was extremely intoxicated at a local theatre where he was to do a presentation. While on stage he began to tell an obscene story about Brigitte Bardot and a champagne bottle, only to stagger offstage and collapse in a nearby seat.[37] Subsequent years saw his health deteriorate. He had to undergo liver surgery but denied any connection to cancer or cirrhosis. His appearances and releases became sparser as he had to rest and recover in Vezelay. During these final years, he released Love on the Beat, a controversial electronic album with mostly sexual themes (examplified by the titular song, for which he sampled actual sexual screams from Bambou), and his last studio album, You're Under Arrest, which presented more synth-driven songs, as well as two live albums.[1]

Film work

- Acting

Gainsbourg appeared in nearly 50 film and television roles. In 1960, he co-starred with Rhonda Fleming in the Italian film La rivolta degli schiavi (The Revolt of the Slaves) as Corvino, the Roman Emperor Massimiano's evil henchman. In 1968 he wrote music for and appeared as himself in Le Pacha directed by Georges Lautner. In 1969, he appeared in William Klein's pop art satire Mr. Freedom, and in the same year he co-starred alongside Jane Birkin in The Pleasure Pit as well as in Slogan, for which he wrote the title song "La Chanson de Slogan". Also with Birkin, he acted in the French-Yugoslav film Devetnaest djevojaka i jedan mornar (19 girls and one sailor) where he played a role of a partisan. They acted together again in Cannabis the following year, and again in Seven Deaths in the Cat's Eye in 1973. He also made a brief appearance with Birkin in Herbert Vesely's 1980 film Egon Schiele – Exzess und Bestrafung.

- Directing

Gainsbourg wrote and directed four feature films: Je t'aime moi non plus, Équateur, Charlotte for Ever, and Stan the Flasher. He also made a short film, Le Physique et le Figuré, and co-wrote the first color film made for French television "Anna."[39][40] He directed a few music videos, including the controversial Morgane de toi for his friend Renaud Seychan, featuring a group of naked children running on a beach.

- Composing

Throughout his career, Gainsbourg wrote the soundtracks for nearly 60 films and television programs. In 1996, he received a posthumous César Award for Best Music Written for a Film for Élisa, along with Zbigniew Preisner and Michel Colombier.

Writing

Gainsbourg wrote a short novel entitled Evguénie Sokolov, a first person narrative where the titular protagonist recounts how he became a famous avant-garde painter by exploiting his uncontrollable and violent farts, generating the trademark shaky graphic style of his works which he calls "gazogrammes".[41]

Death and legacy

Gainsbourg, who smoked five packs of unfiltered Gitane cigarettes a day,[42] died on 2 March 1991 of a heart attack, a month shy of his 63rd birthday. He was buried in the Jewish section of the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris. French President François Mitterrand said of him, "He was our Baudelaire, our Apollinaire ... He elevated the song to the level of art."[43]

Since his death, Gainsbourg's music has reached legendary stature in France.[44] He has also gained a following in the English-speaking world, with numerous artists influenced by his arrangements. One of the most frequent interpreters of Gainsbourg's songs was British singer Petula Clark, whose success in France was propelled by her recordings of his tunes. In 2003, she wrote and recorded La Chanson de Gainsbourg as a tribute to the composer of some of her biggest hits. The majority of Gainsbourg's lyrics are collected in the volume Dernières nouvelles des étoiles.[45]

The Parisian house in which Gainsbourg lived from 1969 until 1991, at 5 bis Rue de Verneuil, remains a celebrated shrine, with his ashtrays and collections of various items, such as police badges and bullets, intact. The outside of the house is covered in graffiti dedicated to Gainsbourg, as well as with photographs of significant figures in his life, including Bardot and Birkin.[46]

Film biopic

Comics artist Joann Sfar wrote and directed a feature film titled Gainsbourg (Vie héroïque), which was released in France in 2010. Gainsbourg is portrayed by Eric Elmosnino and Kacey Mottet Klein. The film won three César Awards, including Best Actor for Elmosnino, and nominated for an additional eight.[47]

Exhibitions

In 2008, Paris' Cité de la Musique held the Gainsbourg 2008 exhibition, curated by sound artist Frédéric Sanchez.[48][49]

Discography

Studio albums

| Year | Album | Chart | Certifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| FR [50][51][52] | |||

| 1958 | Du chant à la une | 137 | |

| 1959 | N° 2 | - | |

| 1961 | L'Étonnant Serge Gainsbourg | - | |

| 1962 | Serge Gainsbourg N° 4 | - | |

| 1963 | Gainsbourg Confidentiel | - | |

| 1964 | Gainsbourg Percussions | - | |

| 1968 | Bonnie & Clyde (with Brigitte Bardot) | - | |

| 1968 | Initials B.B. | - | |

| 1969 | Jane Birkin/Serge Gainsbourg | 4 | |

| 1971 | Histoire de Melody Nelson | 56 | |

| 1973 | Vu de l'extérieur | - | |

| 1975 | Rock around the bunker | 5 | |

| 1976 | L'Homme à tête de chou | 85 | FR: Gold[53] |

| 1979 | Aux armes et cætera | 1 | FR: Platinum[53] |

| 1981 | Mauvaises nouvelles des étoiles | 3 | FR: Gold[53] |

| 1984 | Love on the Beat | 3 | FR: Platinum[53] |

| 1987 | You're Under Arrest | 2 | FR: Platinum[53] |

Live albums

- 1980: Enregistrement public au Théâtre Le Palace (re-released in 2006 as Gainsbourg... et cætera – Enregistrement public au Théâtre Le Palace in an expanded edition)

- 1986: Gainsbourg Live (Casino de Paris)

- 1989: Le Zénith de Gainsbourg

- 2009: 1963 Théâtre des Capucines

Selected film scores

- 1967: Anna

- 1968: Le Pacha

- 1969: Slogan

- 1970: Cannabis (instrumental)

- 1976: Je t'aime moi non plus – Ballade de Johnny-Jane (instrumental)

- 1977: Madame Claude (instrumental)

- 1977: Goodbye Emmanuelle (instrumental)

- 1980: Je vous aime (only three pieces sung by Gainsbourg)

- 1986: Putain de film ! – B.O.F. Tenue de soirée

Singles

- "Black Trombone" (1962)

- "La Javanaise" (1963)

- "Couleur café" (1964)

- "New York U.S.A." (1964)

- "Hold Up" (1967)

- "Initials B.B." (1967)

- "Bonnie and Clyde" (1968) (Brigitte Bardot et Serge Gainsbourg)

- "Élisa" (1969)

- "La chanson de Slogan" / "Evelyne" (1969)

- "Je t'aime... moi non plus" (1969) (Jane Birkin avec Serge Gainsbourg)

- "La Décadanse" (1971) (Jane Birkin et Serge Gainsbourg)

- "Je suis venu te dire que je m'en vais" (1973)

- "La Noyée" (1973)

- "L'Homme à Tête de Chou" (1976)

- "Marilou" (1976)

- "Sea, Sex and Sun" (1978)

- "Aux armes et cætera" (1979)

- "Lola Rastaquouère" (1979)

- "Dieu fumeur de havanes" (1980) (Catherine Deneuve & Serge Gainsbourg)

- "Sorry Angel" (1984)

- "Lemon Incest" (1985) (Charlotte & Gainsbourg)

- "You're Under Arrest" (1987)

- "Mon légionnaire" (1987)

- "Requiem pour un con" (1991)

Editions

- De Gainsbourg à Gainsbarre (1989, 1994, Philips)

- A 207-track survey of Gainsbourg's career from 1959 to 1981 on nine CDs, issued both separately and in a box: Vol. 1 – Le Poinçonneur Des Lilas, 1959-1960; Vol. 2 – La Javanaise, 1961-1963; Vol. 3 – Couleur Café, 1963-1964; Vol. 4 – Initials B.B., 1966-1968; Vol. 5 – Je T'Aime Moi Non Plus, 1969-1971; Vol. 6 – Je Suis Venu Te Dire Que Je M'en Vais, 1973-1975; Vol. 7 – L'Homme à Tête de Chou, 1975-1981; Vol. 8 – Aux Armes et Cætera, 1979-1981; and Vol. 9 – Anna, 1967–1980. A two-CD highlights collection, also called De Gainsbourg à Gainsbarre, was culled from this edition in 1990. The box was reissued in 1994 with two more discs containing the later albums Love on the Beat (1984) and You're Under Arrest (1987).

- Gainsbourg Forever (2001, Mercury)

- An 18-CD box issued to mark the tenth anniversary of Gainsbourg's death containing each of his sixteen studio albums and the EP Essais Pour Signature (1958) in its original format (one per CD), plus a disc of rarities, Inédits, Les Archives 1958-1981. A separate 3-CD box, Le Cinéma de Serge Gainsbourg: Musiques de Films 1959–1990 (2001, Mercury) covered his film music.

- Serge Gainsbourg Intégrale (2011, Philips)

- A 20-CD, 271-track box issued to mark the twentieth anniversary of Gainsbourg's death. The first sixteen discs contain his studio albums and related tracks. They are followed by a disc of singles, a disc of television and radio recordings, and two discs of film music.

Albums written for other artists

- 1973: Di doo dah – Jane Birkin

- 1975: Lolita Go Home – Jane Birkin (about half of the album)

- 1977: Rock'n rose – Alain Chamfort

- 1978: Ex fan des sixties – Jane Birkin

- 1980: Guerre et pets – Jacques Dutronc (about two-thirds of the album)

- 1981: Amour année zéro – Alain Chamfort

- 1981: Souviens-toi de m'oublier – Catherine Deneuve

- 1982: Play blessures – Alain Bashung

- 1983: Isabelle Adjani (or Pull marine) – Isabelle Adjani

- 1983: Baby Alone in Babylone – Jane Birkin

- 1986: Charlotte for Ever – Charlotte Gainsbourg

- 1987: Lost Song – Jane Birkin

- 1989: Made in China – Bambou

- 1990: Amours des feintes – Jane Birkin

- 1990: Variations sur le même t'aime – Vanessa Paradis

Singles written for other artists

- "Laisse tomber les filles" (1964) – France Gall

- "Les Incorruptibles" (1965) – Petula Clark

- "La Gadoue" (1965) – Petula Clark

- "Poupée de cire, poupée de son" (1965) – France Gall

- "Baby Pop" (1966) – France Gall

- "Les Papillons Noirs" (1966) – Michèle Arnaud

- "Ne dis rien" (1967) – Anna Karina

- "Les Sucettes" (1966) – France Gall

- "Comment te dire adieu?" (1968) – Françoise Hardy (lyrics)

- "Betty Jane Rose" (1978) – Bijou

- "Joujou à la casse" (1979) – Alain Chamfort

- "Manureva" (1979) – Alain Chamfort

- "Amour Puissance Six" (1989) – Viktor Lazlo

- "Dis-lui toi que je t'aime" (1990) – Vanessa Paradis

- "White and Black Blues" (1990) – Joëlle Ursull (lyrics by Gainsbourg)

Selected tribute albums and posthumous releases

- 1995: Intoxicated Man (tribute album by Mick Harvey)

- 1997: Pink Elephants (tribute album by Mick Harvey)

- 1997: Great Jewish Music: Serge Gainsbourg (tribute album)

- 1997: Comic Strip (collection of songs recorded between 1966 and 1969)

- 2001: I Love Serge: Electronicagainsbourg (remix album)

- 2005: Monsieur Gainsbourg Revisited (tribute album)

- 2008: Classé X (compilation)

- 2008: Gainsbourg Gainbegiratuz (tribute)

- 2011: Best of Gainsbourg: Comme Un Boomerang (compilation)

- 2016: Delirium Tremens (tribute album by Mick Harvey)

- 2017: Intoxicated Women (tribute album by Mick Harvey)

- 2020 Serge Vie Heroique (tribute tape by Serge Nikos)

Notes

- allmusic Biography

- Macek III, J.C. (13 February 2014). "Serge Gainsbourg's Concept Album, Through the Zeitgeist Darkly". PopMatters. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- Jones, Mikey IQ (10 September 2015). "A beginner's guide to Serge Gainsbourg". Fact. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=U03rivYATpg. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Ginsburg is sometimes spelled Ginzburg in the media, including print encyclopedias and dictionaries. Ginsburg is however the name engraved on Gainsbourg's grave; Lucien Ginsburg is the name by which Gainsbourg is referred to, as a performer, in the Sacem catalog (along with Serge Gainsbourg as the author/composer/adaptor).

- Obituary Variety, 11 March 1991.

- Ankeny, Jason. "Serge Gainsbourg – Music Biography, Credits and Discography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- Simmons, Sylvie (2 February 2001). "An extract from Serge Gainsbourg: A Fistful of Gitanes by Sylvie Simmons". The Guardian.

- Torrance, Kelly Jane. "An Unconventional Film for the Unconventional Serge Gainsbourg". Washington Examiner. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- 2003年4月21日 (月). "The 100 Greatest Artists – No. 62". Hmv.co.jp. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- Robinson, Lisa. "The Secret World of Serge Gainsbourg".

- fr:Liste des chansons de Serge Gainsbourg

- fr:Reprises des chansons de Serge Gainsbourg

- E.W. (12 October 2017). "In "Rest", Charlotte Gainsbourg explores the sharp edges of grief". The Economist.

- Short version: Olia, his mother's baptist name was Olga, as written on Gainsbourg's grave

- Benjamin Ivry: The Man With the Yellow Star: The Jewish Life of Serge Gainsbourg, The Jewish Daily Forward, 26 November 2008.

- Great Jewish Music, Deconstruction in Music.

- "Serge Gainsbourg Biography – life, family, parents, name, story, death, wife, school, young, son, book, old, born, husband, marriage, time, year, scandal, sister, The outsider". Notablebiographies.com. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- LucienGrix No real name given + Add Contact. "1928 Liliane & Lucien Ginsburg | Flickr – Photo Sharing!". Flickr. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- https://www.vanityfair.com, Robinson, Lisa, Legends, "The World of Serge Gainsbourg," November, 2007, retrieved 3 September 2012

- https://forward.com/ Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Ivry, Benjamin, "When You Feel The Jewish Life of Serge Gainsbourg," 26 November 2008, retrieved 4 September 2012

- (fr)Mediatheque Cité Musique

- https://www.vanityfair.com, Robinson, Lisa, Legends, "The World of Serge Gainsbourg," November, 2007, retrieved 3 September 2012

- http://www.notablebiography.com, "Serge Gainsbourg," retrieved 3 September 2012

- Adams, William Lee (26 January 2010). "French Chanteuse Charlotte Gainsbourg". TIME.

- "Best-Looking Couples Ever". LIFE.com. See Your World LLC.

JoAnne Good (9 July 2011). "Inside Travel: Pooches in Paris". independent.co.uk.

"Serge Gainsbourg's women: the music". The Telegraph. 7 February 2011.

"Birkin, Bardot and Gainsbourg, the accidental sex symbol". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. 5 July 2010.

"Jane Birkin". Apple Inc. - "Serge Gainsbourg: "au bois, je me suis fait..."". chartsinfrance.net.

- "Oser en parler » - Ce qu'est réellement l'homosexualité". www.oserenparler.com.

- "Exquis ex-kiss". Libération.fr (in French). 11 October 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Album notes from Initials SG

- Gorman, Francine (28 February 2011). "Serge Gainsbourg's 20 most scandalous moments". The Guardian.

- Batteur Magazine, France, 2003

- Chrisafis, Angelique, The Guardian (14 April 2006). "Gainsbourg, je t'aime". London.

- "Play Blessures". Les Inrocks (in French). Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- Roughly 75 €, but in 1984, 500 FF represented one-sixth of the net minimum monthly wage in France

- Hodgkinson, Will, The Guardian (5 February 2003). "Serge, mon amour". London.

- Kent, Nick, The Guardian (15 April 2006). "What a drag". London.

- A controversial video for Lemon Incest featured a half-naked Gainsbourg lying on a bed with his daughter Charlotte. Phrases from the song include L'amour que nous ne ferons jamais ensemble/ Est le plus beau le plus violent/ Le plus pur le plus enivrant (The love that we will never make together/ is the most beautiful, the most violent/ The most pure, the most heady).

- "Anna". IMDb.com.

- "Serge Gainsbourg". IMDb.com.

- "Tam Tam Books". Tam Tam Books. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- Willsher, Kim (20 July 2016). "Smokers fume as France mulls ban on 'too cool' Gitanes and Gauloises". The Guardian.

- Simmons, Sylvie, The Guardian (2 February 2001). "The eyes have it". London.

- Nuc, Olivier (29 February 2016). "Gainsbourg est en train de remplacer Trenet ou Brassens". Le Figaro.fr (in French). Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Bart Plantenga (2014). "Serge Gainsbourg: The Obscurity of Fame". wfmu.org. wfmu.org. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- Jody Macgregor (16 April 2014). "8 secret music destinations you need to visit right now". Faster Louder. Faster Louder Pty Ltd. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- César Awards 2011 imdb.com

- Holman, Rachel (3 March 2013). "Twenty years on, Gainsbourg remains France's favourite 'enfant terrible'". France 24. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

Frédéric Sanchez, who curated "Gainsbourg 2008" in Paris, describes him as, "one of the most important artists of the 20th century".

- Litchfield, John (23 October 2011). "Je t'aime (again): The French love affair with Serge Gainsbourg". The Independent. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

The curator of the exhibition, Frédéric Sanchez, describes the choice of Gainsbourg as a "consecration" and an "apotheosis".

- Hung, Steffen. "lescharts.com - Discographie Serge Gainsbourg". lescharts.com.

- Lesueur, InfoDisc, Daniel Lesueur, Dominic Durand. "InfoDisc : Tous les Albums classés par Artiste". www.infodisc.fr.

- Lesueur, InfoDisc, Daniel Lesueur, Dominic Durand. "InfoDisc : Tous les Albums classés par Artiste". www.infodisc.fr.

- Lesueur, InfoDisc, Daniel Lesueur, Dominic Durand. "InfoDisc : Les Certifications Officielles des Formats Longs ((33 T. / CD / Albums / Téléchargements depuis 1973". www.infodisc.fr.

References

- Serge Gainsbourg: View From The Exterior by Alan Clayson (1998). Sanctuary. ISBN 978-1-86074-222-4

- Serge Gainsbourg: A Fistful of Gitanes by Sylvie Simmons (2002). Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81183-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Serge Gainsbourg. |

- (in French) Serge Gainsbourg official site

- Serge Gainsbourg on IMDb

- Serge Gainsbourg discography at Discogs