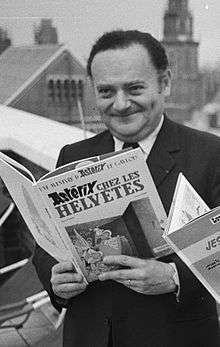

René Goscinny

René Goscinny (French: [ʁəne ɡosini], Polish: [ɡɔɕˈtɕinnɨ] (![]()

| René Goscinny | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 14 August 1926 Paris, France |

| Died | 5 November 1977 (aged 51) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Area(s) | Cartoonist, Writer, Editor |

| Pseudonym(s) | d'Agostini, Stanislas |

Notable works | Astérix Iznogoud Le Petit Nicolas Lucky Luke Oumpah-pah |

| Collaborators | Albert Uderzo Jean-Jacques Sempé Morris Marcel Gotlib Jean Tabary |

| Awards | full list |

| Spouse(s) | Gilberte Pollaro-Millo (1967–1977; his death; 1 child) |

He wrote Iznogoud with Jean Tabary. Goscinny also wrote a series of children's books known as Le Petit Nicolas (Little Nicolas).

Early life

Goscinny was born in Paris in 1926, to Jewish immigrants from Poland.[2] His parents were Stanisław Simkha Gościnny (the surname means "hospitable" in Polish; Simkha is Jewish, meaning "happiness"), a chemical engineer from Warsaw, and Anna (Hanna) Bereśniak-Gościnna from Chodorków, a small village near Zhytomyr in the Second Polish Republic (now part of Ukraine).[3] Goscinny's maternal grandfather, Abraham Lazare Berezniak, founded a printing company. [4] Claude, Goscinny's older brother, was six years older, born on 10 December 1920.

Stanisław and Anna had met in Paris and married in 1919. When René was two, the Gościnnys moved to Buenos Aires, Argentina, because his father had been hired as a chemical engineer there. René had a happy childhood in Buenos Aires and studied in French-language schools there. He was often the "class clown", probably to compensate for a natural shyness. He started drawing very early on, inspired by the illustrated stories which he enjoyed reading.

In December 1943, the year after Goscinny graduated from lycée or high school, his father died of a cerebral hemorrhage (stroke). The youth had to go to work. The next year, he got his first job, as an assistant accountant in a tire recovery factory. After being laid off the following years, Goscinny became a junior illustrator in an advertising agency.[5]

Goscinny, along with his mother, emigrated from Argentina and immigrated to New York, United States in 1945, to join her brother Boris. To avoid service in the United States Armed Forces, he travelled to France to join the French Army in 1946. He served at Aubagne, in the 141st Alpine Infantry Battalion. Promoted to senior corporal, he became the appointed artist of the regiment and drew illustrations and posters for the army.

First works

The following year, Goscinny worked on an illustrated version of the Balzac short story "The Girl with the Golden Eyes."[6] In April of that year he returned to New York.

There he went through the most difficult period of his life. For a while, Goscinny was jobless, alone, and living in poverty. By 1948, though, he had begun working in a small studio, where he became friends with future MAD Magazine contributors Will Elder, Jack Davis, and Harvey Kurtzman.[5] Goscinny became art director at Kunen Publishers, where he wrote four books for children.

Around this time he met two Belgian comic artists, Joseph Gillain, better known as Jijé, and Maurice de Bevere, also known as Morris. Morris lived in the US for six years, having already started his cartoon series Lucky Luke. (He and Goscinny collaborated on this, with Goscinny writing it from 1955 until his death in 1977, a period described as its golden age).[5]

Georges Troisfontaines, chief of the World Press agency, convinced Goscinny to return to France in 1951 in order to work for his agency as the head of the Paris office. There he met Albert Uderzo, with whom he started a longtime collaboration.[5][7] They started out with some work for Bonnes Soirées, a women's magazine for which Goscinny wrote Sylvie. Goscinny and Uderzo also launched the series Jehan Pistolet and Luc Junior, in the magazine La Libre Junior.

In 1955, Goscinny, together with Uderzo, Jean-Michel Charlier, and Jean Hébrad, founded the syndicate Edipress/Edifrance. The syndicate launched publications such as Clairon for the factory union and Pistolin for a chocolate company. Goscinny and Uderzo cooperated on the series Bill Blanchart in Jeannot, Pistolet in Pistolin, and Benjamin et Benjamine in the magazine of the same name. Under the pseudonym Agostini, Goscinny wrote Le Petit Nicolas for Jean-Jacques Sempé in Le Moustique. It was later published in Sud-Ouest and Pilote magazines.

In 1956, Goscinny began a collaboration with Tintin magazine. He wrote some short stories for Jo Angenot and Albert Weinberg, and worked on Signor Spaghetti with Dino Attanasio, Monsieur Tric with Bob de Moor, Prudence Petitpas with Maurice Maréchal, Globul le Martien and Alphonse with Tibet, Strapontin with Berck and Modeste et Pompon with André Franquin. An early creation with Uderzo, Oumpah-pah, was also adapted for serial publication in Tintin from 1958-1962.[8] In addition, Goscinny appeared in the magazines Paris-Flirt (Lili Manequin with Will) and Vaillant (Boniface et Anatole with Jordom, Pipsi with Godard).

Pilote and Astérix (1959)

In 1959, the Édifrance/Édipresse syndicate started the Franco-Belgian comics magazine Pilote.[9] Goscinny became one of the most productive writers for the magazine. In the magazine's first issue, he launched Astérix, with Uderzo. The series was an instant hit and remains popular worldwide. Goscinny also restarted the series Le Petit Nicolas and Jehan Pistolet, now called Jehan Soupolet. Goscinny also began Jacquot le Mousse and Tromblon et Bottaclou with Godard.

The magazine was bought by Georges Dargaud in 1960, and Goscinny became editor-in-chief. He also began new series like Les Divagations de Monsieur Sait-Tout (with Martial), La Potachologie Illustrée (with Cabu), Les Dingodossiers (with Gotlib) and La Forêt de Chênebeau (with Mic Delinx). With Tabary, he launched Calife Haroun El Poussah in Record, a series that was later continued in Pilote as Iznogoud. With Raymond Macherot he created Pantoufle for Spirou.

Family

Goscinny married Gilberte Pollaro-Millo in 1967. In 1968 their daughter Anne Goscinny was born. She also became an author.

Death

Goscinny died at 51, in Paris of cardiac arrest on 5 November 1977, during a routine stress test at his doctor's office.[10] He was buried in the Jewish Cemetery of Nice. In accordance with his will, most of his money was transferred to the chief rabbinate of France.

After Goscinny's death, Uderzo began to write Asterix himself and continued the series, although at a much slower pace, until passing the series over in 2011 to writer Jean-Yves Ferri and illustrator Didier Conrad.[11] Tabary similarly began to write Iznogoud himself, whereas Morris continued Lucky Luke with various other writers.

In a tribute to Goscinny, Uderzo gave his likeness to one of the characters in the 1981 L'Odyssée d'Astérix ("Asterix and the Black Gold").

Awards and honors

- 1974: Adamson Award for best international comic strip artist, Sweden

- 2005: Inducted in the Will Eisner Hall of Fame as a Judges' choice, U.S.

Since 1996, the René Goscinny Award is presented at the yearly Angoulême International Comics Festival in France as an encouragement for young comic writers.

According to UNESCO's Index Translationum, Goscinny, as of August 2017, was the 20th most-translated author, with 2,200 translations of his work.[12]

On 23 January 2020, a life-sized bronze statue of Goscinny was unveiled near his former home in Paris. It was the first public statue in Paris dedicated to a comic book author.[13]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Asterix and Cleopatra | Commentator | Voice, Uncredited |

| 1978 | La Ballade des Dalton | Jolly Jumper, le cheval de Lucky Luke | Voice, (final film role) |

Bibliography

| Series | Years | Magazine | Albums | Editor | Artist |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lucky Luke[b] | 1955–1977 | Spirou and Pilote | 38 | Dupuis and Dargaud | Morris |

| Modeste et Pompon[a][b] | 1955–1958 | Tintin | 2 | Lombard | André Franquin |

| Prudence Petitpas | 1957–1959 | Tintin | Lombard | Maurice Maréchal | |

| Signor Spaghetti | 1957–1965 | Tintin | 15 | Lombard | Dino Attanasio |

| Oumpah-pah | 1958–1962 | Tintin | 3 | Lombard | Albert Uderzo |

| Strapontin | 1958–1964 | Tintin | 4 | Lombard | Berck |

| Astérix[b] | 1959–1977 | Pilote | 24 | Dargaud | Albert Uderzo |

| Le Petit Nicolas | 1959–1965 | Pilote | 5 | Denoël | Sempé |

| Iznogoud[b] | 1962–1977 | Record and Pilote | 14 | Dargaud | Jean Tabary |

| Les Dingodossiers | 1965–1967 | Pilote | 3 | Dargaud | Gotlib |

Notes

- Annessa Ann Babic (11 December 2013). Comics as History, Comics as Literature: Roles of the Comic Book in Scholarship, Society, and Entertainment. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-1-61147-557-9.

- Garcia, Laure. "Uderzo, le dernier Gaulois". Le Nouvel Observateur (in French).

- According to Yeruham Eniss, the village had a soap factory, and many Jews of nearby Chodorków had jobs selling and trading in soap. A census made in the late 1930s counted 3670 Jewish families in Chodorków before World War II (ShtetLinks website: alternate spellings include Chortkow and Khodorkov)

- https://www.timesofisrael.com/the-wild-adventures-of-rene-goscinny-jewish-inventor-of-asterix-and-obelix/

- Lambiek Comiclopedia. "René Goscinny".

- Honoré de Balzac, La fille aux yeux d'or, Paris : Éditions du livre français, collection "Les classiques du XIXe", 1946.

- Lagardère. "Release of the 33rd Asterix volume".

- Asterix International!. "Albert Uderzo".

- BDoubliées. "Pilote année 1959" (in French).

- "Le gag raté de Goscinny : mourir d'un arrêt du cœur chez son cardiologue". Sciences et Avenir (in French). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- Iovene, Franck. "Italy beckons for Gaul comic heros Asterix and Obelix". www.timesofisrael.com.

- UNESCO Statistics. "Index Translationum - "TOP 50" Author". Official website of UNESCO. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- "By Toutatis! France unveils statue to Asterix creator". France24.com. AFP. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

References

- Goscinny publications in Pilote, Spirou, French Tintin and Belgian Tintin BDoubliées (in French)

- Goscinny albums Bedetheque (in French)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to René Goscinny. |

- Goscinny official site (in French)

- Astérix official site

- On Dupuis.com

- Goscinny biography on Asterix International!

- Goscinny biography on Lambiek Comiclopedia

- Daughter Ann lighting Hanuka candles with family.

- René Goscinny on IMDb