Danelaw

The Danelaw (/ˈdeɪnˌlɔː/, also known as the Danelagh; Old English: Dena lagu;[1] Danish: Danelagen), as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, is a historical name given to the part of England in which the laws of the Danes held sway[2] and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. Danelaw contrasts with West Saxon law and Mercian law. The term is first recorded in the early 11th century as Dena lage.[3] Modern historians have extended the term to a geographical designation. The areas that constituted the Danelaw lie in northern and eastern England.

Danelaw | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

The raven banner | |||||||||||||||||

England, 878 | |||||||||||||||||

| Status | Confederacy under the Kingdom of Denmark | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Norse, Old English | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Formed | 865 | ||||||||||||||||

• Conquered | 954 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||

The Danelaw originated from the Viking expansion of the 9th century, although the term was not used to describe a geographic area until the 11th century. With the increase in population and productivity in Scandinavia, Viking warriors, having sought treasure and glory in the nearby British Isles, "proceeded to plough and support themselves", in the words of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for the year 876.[4]

Danelaw can describe the set of legal terms and definitions created in the treaties between the King of Wessex, Alfred the Great, and the Danish warlord, Guthrum, written following Guthrum's defeat at the Battle of Edington in 878.

In 886, the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum was formalised, defining the boundaries of their kingdoms, with provisions for peaceful relations between the English and the Vikings. The language spoken in England was also affected by this clash of cultures with the emergence of Anglo-Norse dialects.[5]

The Danelaw roughly comprised 15 shires: Leicester, York, Nottingham, Derby, Lincoln, Essex, Cambridge, Suffolk, Norfolk, Northampton, Huntingdon, Bedford, Hertford, Middlesex, and Buckingham.[6][7][8]

Background

Scandinavian York

From around 800, there had been waves of Norse raids on the coastlines of the British Isles. In 865, instead of raiding, the Danes landed a large army in East Anglia, with the intention of conquering the four Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England. The armies of various Danish leaders had come together to provide one combined force under a leadership that included Halfdan Ragnarsson and Ivar the Boneless, the sons of the legendary Viking leader Ragnar Lodbrok.[9] The combined army was described in the annals as the Great Heathen Army.[10] After making peace with the local East Anglian king in return for horses, the Great Heathen Army moved north. In 867, they captured Northumbria and its capital, York, defeating both the recently deposed King Osberht of Northumbria and the usurper Ælla of Northumbria. The Danes then placed an Englishman, Ecgberht I of Northumbria, on the throne of Northumbria as a puppet ruler.[11]

King Æthelred of Wessex and his brother, Alfred, led their army against the Danes at Nottingham, but the Danes refused to leave their fortifications. King Burgred of Mercia then negotiated peace with Ivar, with the Danes keeping Nottingham in exchange for leaving the rest of Mercia alone.

Under Ivar the Boneless, the Danes continued their invasion in 869 by defeating King Edmund of East Anglia at Hoxne and conquering East Anglia.[12] Once again, the brothers Æthelred and Alfred attempted to stop Ivar by attacking the Danes at Reading. They were repelled with heavy losses. The Danes pursued, and on 7 January 871, Æthelred and Alfred defeated the Danes at the Battle of Ashdown. The Danes retreated to Basing (in Hampshire), where Æthelred attacked and was, in turn, defeated. Ivar was able to follow up this victory with another in March at Meretum (now Marton, Wiltshire).

On 23 April 871, King Æthelred died and Alfred succeeded him as King of Wessex. His army was weak and he was forced to pay tribute to Ivar in order to make peace with the Danes. During this peace, the Danes turned to the north and attacked Mercia, a campaign that lasted until 874. Both the Danish leader Ivar and the Mercian leader Burgred died during this campaign. Ivar was succeeded by Guthrum, who finished the campaign against Mercia. In ten years, the Danes had gained control over East Anglia, Northumbria and Mercia, leaving just Wessex resisting.[13]

Guthrum and the Danes brokered peace with Wessex in 876, when they captured the fortresses of Wareham and Exeter. Alfred laid siege to the Danes, who were forced to surrender after reinforcements were lost in a storm. Two years later, Guthrum again attacked Alfred, surprising him by attacking his forces wintering in Chippenham. King Alfred was saved when the Danish army coming from his rear was destroyed by inferior forces at the Battle of Cynuit.[14][15] The modern location of Cynuit is disputed but suggestions include Countisbury Hill, near Lynmouth, Devon, or Kenwith Castle, Bideford, Devon, or Cannington, near Bridgwater, Somerset.[16] Alfred was forced into hiding for a time, before returning in the spring of 878 to gather an army and attack Guthrum at Edington. The Danes were defeated and retreated to Chippenham, where King Alfred laid siege and soon forced them to surrender. As a term of surrender, King Alfred demanded that Guthrum be baptised a Christian; King Alfred served as his godfather.[17]

Establishment of Danish self-rule

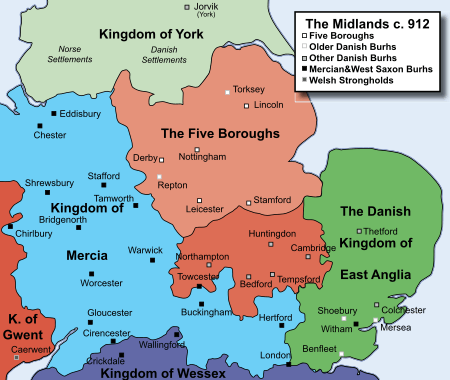

Edward the Elder and his sister, Æthelflæd, the Lady of the Mercians, conquered Danish territories in the Midlands and East Anglia in a series of campaigns in the 910s, and some Danish jarls who submitted were allowed to keep their lands.[18] Viking rule ended when Eric Bloodaxe was driven out of Northumbria in 954.

The reasons for the waves of immigration were complex and bound to the political situation in Scandinavia at that time; moreover, they occurred when Viking settlers were also establishing their presence in the Hebrides, Orkney, the Faroe Islands, Ireland, Iceland, Greenland, L'Anse aux Meadows, France (Normandy), the Baltic, Russia and Ukraine (see Kievan Rus').[19]

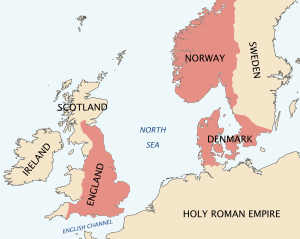

Cnut and his successors

The Danes did not give up their designs on England. From 1016 to 1035, Cnut the Great ruled over a unified English kingdom, itself the product of a resurgent Wessex, as part of his North Sea Empire, together with Denmark, Norway and part of Sweden. Cnut was succeeded in England on his death by his son Harold Harefoot, until he died in 1040, after which another of Cnut's sons, Harthacnut, took the throne. Since Harthacnut was already on the Danish throne, this reunited the North Sea Empire. Harthacnut lived only another two years, and from his death in 1042 until 1066 the monarchy reverted to the English line in the form of Edward the Confessor.

Edward died in January 1066 without an obvious successor, and an English nobleman, Harold Godwinson, took the throne. In the autumn of that same year, two rival claimants to the throne led invasions of England in short succession. First, Harald Hardrada of Norway took York in September, but was defeated by Harold at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, in Yorkshire. Then, three weeks later, William of Normandy defeated Harold at the Battle of Hastings, in Sussex, and in December he accepted the submission of Edgar the Ætheling, last in the line of Anglo-Saxon royal succession, at Berkhamsted.

The Danelaw appeared in legislation as late as the early 12th century with the Leges Henrici Primi, where it is referred to as one of the laws together with those of Wessex and Mercia into which England was divided.

Danish–Norwegian conflict in the North Sea

In the 11th century, when King Magnus I had freed Norway from Cnut the Great, the terms of the peace treaty provided that the first of the two kings Magnus (Norway) and Harthacnut (Denmark) to die would leave their dominion as an inheritance to the other. When Edward the Confessor ascended the throne of a united Dano-Saxon England, a Norse army was raised from every Norwegian colony in the British Isles and attacked Edward's England in support of Magnus', and after his death, his brother Harald Hardrada's, claim to the English throne. On the accession of Harold Godwinson after the death of Edward the Confessor, Hardrada invaded Northumbria with the support of Harold's brother Tostig Godwinson, and was defeated at the Battle of Stamford Bridge, three weeks before William I's victory at the Battle of Hastings.

Chronology

800 − Waves of Danish assaults on the coastlines of the British Isles.

865 − Danish raiders first begin to settle in England. Led by the brothers Halfdan and Ivar the Boneless, they wintered in East Anglia, where they demanded and received tribute in exchange for a temporary peace. From there, they move north and attack Northumbria, which is in the midst of a civil war between the deposed king Osberht and a usurper Ælla. The Danes use the civil turmoil as an opportunity to capture York, which they sack and burn.

867 − Following the loss of York, Osberht and Ælla form an alliance against the Danes. They launch a counter-attack, but the Danes kill both Osberht and Ælla and set up a puppet king on the Northumbrian throne. In response, King Æthelred of Wessex, along with his brother Alfred, march against the Danes, who are positioned behind fortifications in Nottingham, but are unable to draw them into battle. In order to effect peace, King Burgred of Mercia cedes Nottingham to the Danes in exchange for leaving the rest of Mercia undisturbed.

868 − Danes capture Nottingham

869 − Ivar the Boneless returns and demands tribute from King Edmund of East Anglia.

870 − King Edmund refuses Ivar's demand. Ivar defeats and captures Edmund at Hoxne, adding East Anglia to the area controlled by the invading Danes. King Æthelred and Alfred attack the Danes at Reading, but are repulsed with heavy losses. The Danes pursue them.

871 − On 7 January, Æthelred and Alfred make their stand at Ashdown (on what is the Berkshire/North Wessex Downs now in Oxfordshire). Æthelred could not be found at the start of battle, as he was busy praying in his tent, so Alfred leads the army into battle. Æthelred and Alfred defeat the Danes, who count among their losses five jarls (nobles). The Danes retreat and set up fortifications at Basing (Basingstoke) in Hampshire, a mere 14 miles (23 km) from Reading. Æthelred attacks the Danish fortifications and is routed. The Danes follow up with another victory in March at Meretum (now Marton, Wiltshire).

King Æthelred dies on 23 April 871 and Alfred takes the throne of Wessex. For the rest of the year Alfred concentrates on attacking with small bands against isolated groups of Danes. He is moderately successful in this endeavour and is able to score minor victories against the Danes, but his army is on the verge of collapse. Alfred responds by paying off the Danes in order for a promise of peace. During the peace, the Danes turn north and attack Mercia, which they finish off in short order, and capture London in the process. King Burgred of Mercia fights in vain against Ivar the Boneless and his Danish invaders for three years until 874, when he flees to Europe. During Ivar's campaign against Mercia he dies and is succeeded by Guthrum the Old. Guthrum quickly defeats Burgred and places a puppet on the throne of Mercia. The Danes now control East Anglia, Northumbria and Mercia, with only Wessex continuing to resist.

875 − The Danes settle in Dorset, well inside of Alfred's Kingdom of Wessex, but Alfred quickly makes peace with them.

876 − The Danes break the peace when they capture the fortress of Wareham, followed by a similar capture of Exeter in 877.

877 − Alfred lays in a siege, while the Danes wait for reinforcements from Scandinavia. Unfortunately for the Danes, the fleet of reinforcements encounter a storm and lose more than 100 ships, and the Danes are forced to return to East Mercia in the north.

878 − In January, Guthrum leads an attack against Wessex that seeks to capture Alfred while he winters in Chippenham. Another Danish army landed in south Wales arrives and moves south with the intent of intercepting Alfred should he flee from Guthrum's forces. However, they stop during their march to capture a small fortress at Countisbury Hill, held by a Wessex ealdorman named Odda. The Saxons, led by Odda, attack the Danes while they sleep and defeat their superior forces, saving Alfred from being trapped between the two armies. Alfred is forced to go into hiding for the rest of the winter and spring of 878 in the Somerset marshes in order to avoid the superior Danish forces. In the spring, Alfred is able to gather an army and attacks Guthrum and the Danes at Edington. The Danes are defeated and retreat to Chippenham, where the English pursue and lay siege to Guthrum's forces. The Danes are unable to hold out without relief and soon surrender. Alfred demands as a term of the surrender that Guthrum become baptised as a Christian, which Guthrum agrees to do, with Alfred acting as his godfather. Guthrum is true to his word and settles in East Anglia, at least for a while.

884 − Guthrum attacks Kent, but is defeated by the English. This leads to the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum, which establishes the boundaries of the Danelaw and allows for Danish self-rule in the region.[20]

902 − Essex submits to Æthelwald.

903 − Æthelwald incites the East Anglian Danes into breaking the peace. They ravage Mercia before winning a pyrrhic victory that saw the death of Æthelwald and the Danish King Eohric; this allows Edward the Elder to consolidate power.

911 − The English defeat the Danes at the Battle of Tettenhall. The Northumbrians ravage Mercia but are trapped by Edward and forced to fight.

917 − In return for peace and protection, the Kingdoms of Essex and East Anglia accept Edward the Elder as their suzerain overlord.

Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, takes the borough of Derby.

918 − The borough of Leicester submits peaceably to Æthelflæd's rule. The people of York promise to accept her as their overlord, but she dies before this could come to fruition. She is succeeded by her brother, the Kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex united in the person of King Edward.

919 − Norwegian Vikings under King Ragnvald Sygtryggsson of Dublin take York.

920 − Edward is accepted as father and lord by the King of the Scots, by Rægnold, the sons of Eadulf, the English, Norwegians, Danes and others all of whom dwell in Northumbria and the King and people of the Strathclyde Welsh.

954 − King Eric is driven out of Northumbria, his death marking the end of the prospect of a Northern Viking Kingdom stretching from York to Dublin and the Isles.

1002 - St. Brice's Day massacre of the Danes

1066 − Harald Hardrada lands with an army, hoping to take control of York and the English crown. He is defeated and killed at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. This event is often cited as the end of the Viking era. The same year, William the Conqueror, himself a descendant of Vikings, successfully took the English throne and became the first Norman king of England.

1069 − Sweyn II of Denmark lands with an army, in much the same way as Harald Hardrada. He took control of York after defeating the Norman garrison and inciting a local uprising. King William eventually defeated his forces and devastated the region in the Harrying of the North.

1075 − One of Sweyn's sons, Knut, set sail for England to support an English rebellion, but it had been crushed before he arrived, so he settled for plundering the city of York and surrounding area, before returning home.[21]

1085 − Knut, now king, planned a major invasion against England but the assembled fleet never sailed. Other than Eystein II of Norway taking advantage of the civil war during Stephen's reign, to plunder the east coast of England,[22] there were no serious invasions or raids of England by the Danes after this.[21]

Geography

The area occupied by the Danelaw was roughly the area to the north of a line drawn between London and Chester, excluding the portion of Northumbria to the east of the Pennines.

Five fortified towns became particularly important in the Danelaw: Leicester, Nottingham, Derby, Stamford and Lincoln, broadly delineating the area now called the East Midlands. These strongholds became known as the Five Boroughs. Borough derives from the Old English word burh (cognate with German Burg, meaning castle), meaning a fortified and walled enclosure containing several households, anything from a large stockade to a fortified town. The meaning has since developed further.

Legal concepts

The Danelaw was an important factor in the establishment of a civilian peace in the neighbouring Anglo-Saxon and Viking communities. It established, for example, equivalences in areas of legal contentiousness, such as the amount of reparation that should be payable in wergild.

Many of the legalistic concepts were compatible; for example, the Viking wapentake, the standard for land division in the Danelaw, was effectively interchangeable with the hundred. The use of the execution site and cemetery at Walkington Wold in east Yorkshire suggests a continuity of judicial practice.[24]

Under the Danelaw, between 30% and 50% of the population in the countryside had the legal status of 'sokeman', occupying an intermediate position between the free tenants and the bond tenants.[25] This tended to provide more autonomy for the peasants. A sokeman was a free man within the lord's soke, or jurisdiction.[26]

According to many scholars, "... the Danelaw was an especially ‘free’ area of Britain because the rank and file of the Danish armies, from whom sokemen were descended, had settled in the area and imported their own social system."[27] The importance of this special legal status also continued after the Conquest.

Legacy

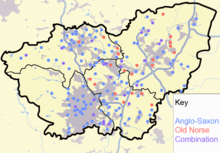

The influence of this period of Scandinavian settlement can still be seen in the North of England and the East Midlands, and is particularly evident in place-names: name endings such as -howe, -by (meaning "village") or -thorp ("hamlet") having Norse origins. There seems to be a remarkable number of Kirby/Kirkby names, some with remains of Anglo-Saxon building[28] indicating both a Norse origin and early church building.[29] Scandinavian names blended with the English -ton give rise to typical hybrid place-names.[30]

Old East Norse and Old English were still somewhat mutually comprehensible. The contact between these languages in the Danelaw caused the incorporation of many Norse words into the English language, including the word law itself, sky and window, and the third person pronouns they, them and their.[31] Many Old Norse words still survive in the dialects of Northern England.[32][33][34]

Four of the five boroughs became county towns—of the counties of Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. However, Stamford failed to gain such status—perhaps because of the nearby autonomous territory of Rutland.

Genetic heritage

In 2000, the BBC commissioned a genetic survey of the British Isles by a team from University College London led by Professor David Goldstein for its programme 'Blood of the Vikings'. It concluded that Norse invaders settled sporadically throughout the British Isles with a particular concentration in certain areas, such as Orkney and Shetland.[35] In this finding, the Vikings refers to Norwegian Vikings only, as the study did not set out to genetically distinguish descendants of Danish Vikings from descendants of Anglo-Saxon settlers. That was decided on the basis that the latter two groups originated from areas that overlap each other on the continental North Sea coast (ranging from the Jutland Peninsula to Belgium) and were therefore deemed inconvenient or difficult to genetically distinguish.[36] A further genetic study in 2015 found some evidence that, after Anglo-Saxon migrants began settling (400s CE), their communities had lived alongside indigenous 'British' ones, and not intermingled for the first hundred years before going on to become a homogenous genetic group.[37] The same study did not find any evidence for a significant legacy of Viking genes in England from the raiding period.

Archaeology

Major archaeological sites that bear testimony to the Danelaw are few. The most famous is the site at York. Another Danelaw site is the cremation site at Heath Wood, Ingleby, Derbyshire.

Archaeological sites do not bear out the historically defined area as being a real demographic or trade boundary. This could be due to misallocation of the items and features on which this judgement is based as being indicative of either Anglo-Saxon or Norse presence. Otherwise, it could indicate that there was considerable population movement between the areas, or simply that after the treaty was made, it was ignored by one or both sides.

Thynghowe was an important Danelaw meeting place, today located in Sherwood Forest, in Nottinghamshire. The word "howe" often indicates a prehistoric burial mound. Howe is derived from the Old Norse word Haugr meaning mound.[38] The site's rediscovery was made by Lynda Mallett, Stuart Reddish and John Wood. The site had vanished from modern maps and was essentially lost to history until the local history enthusiasts made their discoveries. Experts think the rediscovered site, which lies amidst the old oaks of an area known as the Birklands in Sherwood Forest, may also yield clues as to the boundary of the ancient Anglo Saxon kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria. English Heritage recently inspected the site and believes it is a national rarity. Thynghowe[39] was a place where people came to resolve disputes and settle issues. It is a Norse word, although the site may be older still, perhaps even from the Bronze Age.

See also

- List of generic forms in British place names

- Longhouse

- Mjöllnir

- Norse–Gaels

- Raven banner

- Runestone

- Stave church

- Subpoena ad testificandum

- Valknut

- Anglo-Scandinavian

- Scandinavian Scotland

- Scandinavian York

- List of monarchs of Northumbria

- Kingdom of Dublin

- Kingdom of the Isles

- English language in Northern England

- Viking activity in the British Isles

References

- M. Pons-Sanz (2007). Norse-derived Vocabulary in late Old English Texts: Wulfstan's Works. A Case Study. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 71. ISBN 87-7674-196-6.

- "The Old English word Dene 'Danes' usually refers to Scandinavians of any kind; most of the invaders were indeed Danish (East Norse speakers), but there were Norwegians (West Norse [speakers]) among them as well." —Lass, Roger, Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion, p. 187, n. 12. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Abrams, Lesley (2001). "Edward the Elder's Danelaw". In Higham, N. J.; Hill, D. H. (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 0-415-21497-1.

- Quoted by Richard Hall, Viking Age Archaeology (series Shire Archaeology), 2010:22; Gwyn Jones, A History of the Vikings. Revised ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984: 221.

- "Danelaw Heritage". The Viking Network. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- K. Holman, The Northern Conquest: Vikings in Britain and Ireland, p. 157

- S. Thomason, T. Kaufman, Language Contact, Creolisation and Genetic Linguistics, p. 362

- The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Michael Lapidge (2008), p. 136

- Sawyer. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. pp. 52–55

- ASC 865 – English translation at project Gutenberg. Retrieved 16 January 2013

- Flores Historiarum: Rogeri de Wendover, Chronica sive flores historiarum, pp. 298–99. ed. H. Coxe, Rolls Series, 84 (4 vols, 1841–42)

- Haywood, John. The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Vikings, p. 62. Penguin Books. 1995.

- Carr, Michael. "Alfred the Great Strikes Back", p. 65. Military History Journal. June 2001.

- Abels, Richard (1998). Alfred the Great: War, Kingship and Culture in Anglo-Saxon England. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 153–54. ISBN 0-582-04047-7.

- ASC 878 – English translation at project Gutenberg. Retrieved 9 June 2014

- Kendrick, T.D. (1930). A History of the Vikings. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 238.

- Hadley, D. M. The Northern Danelaw: Its Social Structure, c. 800–1100. p. 310. Leicester University Press. ©2000.

- Lesley Abrams, 'Edward the Elder's Danelaw', in N. J. Higham & D. H. Hill eds, Edward the Elder 899–924, Routledge, 2001, pp. 138–39

- "The Viking expansion". hgo.se. Archived from the original on 12 May 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- Attenborough, F.L. Tr., ed. (1922). The laws of the earliest English kings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–101. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- Sawyer, Peter (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings (3rd ed.). Oxford: OUP. pp. 17–18. ISBN 0-19-285434-8.

- Forte, Angello (2005). Viking Empires. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 216. ISBN 0521829925.

- Falkus & Gillingham and Hill

- J.L. Buckberry & D.M. Hadley, "An Anglo-Saxon Execution Cemetery at Walkington Wold, Yorkshire", Oxford Journal of Archaeology 26(3) 2007, 325

- Emma Day (2011), SOKEMEN AND FREEMEN IN LATE ANGLO-SAXON EAST ANGLIA IN COMPARATIVE CONTEXT. (PDF) cam.ac.uk

- What is Sac and Soke in Anglo-Saxon England? (2015)

- Emma Day (2011), SOKEMEN AND FREEMEN IN LATE ANGLO-SAXON EAST ANGLIA IN COMPARATIVE CONTEXT. (PDF) p. 21, cam.ac.uk

- Taylor, H.M. & Taylor, Joan, Anglo-Saxon Architecture. Cambridge, 1965.

- introduction, Biddulph, Joseph Old Danish of the Old Danelaw. Pontypridd, 2003. ISBN 978-1-897999-48-6.

- The "Grimston hybrids", noted by Richard Hall, Viking Age Archaeology (series Shire Archaeology) 2010:22.

- Henry Loyn, The Vikings in Britain (Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers, 1995), 85.

- Joan Beal, "English Dialects in the North of England: Morphology and Syntax," in A Handbook of Varieties of English vol. 2, ed. Bernd Kortmann et al. (New York: Martin De Gruyter, 2004) 137.

- Katie Wales, Northern English: A Social and Cultural History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006),55.

- G.H. Cowling, The Dialect of Hackness:Northeast Yorkshire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1915), xxi–xxii.

- "ENGLAND | Viking blood still flowing". BBC News. 3 December 2001. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- "Blood of the Vikings". Genetic Archaeology. 2014. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Ghosh, Pallab (18 March 2015). "DNA study: Celts not a single group". Retrieved 27 March 2018 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- Stahl, Anke-Beate (May 2004). "Guide to Scandinavian origins of place names in Britain" (PDF). Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- "Detailed Result: THYNGHOWE". Pastscape. 22 November 2007. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

Further reading

- Abrams, Lesley (2001). "Edward the Elder's Danelaw". In Higham, N. J.; Hill, D. H. (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 128–43. ISBN 0-415-21497-1. Discusses definitions of "Danelaw".

- Types of Manorial Structure in the Northern Danelaw, Frank M. Stenton, London, 1910.

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, Tiger Books International version translated and collated by Anne Savage,1995.

- Community archaeology at Thynghowe, Birklands, Sherwood Forest by Lynda Mallett, Stuart Reddish, John Baker, Stuart Brookes and Andy Gaunt; Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire, Volume 116 (2012)

- Mawer, Allen (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 803–04.

External links

- News Item: BBC Blood of the Vikings

- BBC Viking History Links

- According to Ancient Custom: Research on the possible Origins and Purpose of Thynghowe Sherwood Forest