Lynmouth

Lynmouth is a village in Devon, England, on the northern edge of Exmoor. The village straddles the confluence of the West Lyn and East Lyn rivers, in a gorge 700 feet (210 m) below Lynton, which was the only place to expand to once Lynmouth became as built-up as possible. The villages are connected by the Lynton and Lynmouth Cliff Railway, which works two cable-connected cars by gravity, using water tanks.

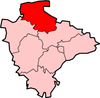

The two villages are a civil parish governed by Lynton and Lynmouth Town Council. The parish boundaries extend southwards from the coast, and include hamlets such as Barbrook and small moorland settlements such as East Ilkerton, West Ilkerton and Shallowford.

The South West Coast Path and Tarka Trail pass through, and the Two Moors Way runs from Ivybridge in South Devon to Lynmouth; the Samaritans Way South West runs from Bristol to Lynton, and the Coleridge Way from Nether Stowey to Lynmouth.

Lynmouth was described by Thomas Gainsborough, who honeymooned there with his bride Margaret Burr, as "the most delightful place for a landscape painter this country can boast".

The Sillery Sands beach [lower-alpha 1] is just off the South West Coast Path and is used by naturists.[1]

Percy Bysshe Shelley, his wife Harriet and his sister-in-law Eliza stayed in Lynmouth between June and August 1812. Shelley worked on political pamphlets and on the poem "Queen Mab". He was delighted with the village.[2]

Lynmouth Lifeboat

A lifeboat station was established in Lynmouth on 20 January 1869, five months after the sailing vessel Home was wrecked nearby. The lifeboat was kept in a shed on the beach, until a purpose-built boat house was built at the harbour. This was rebuilt in 1898 and enlarged in 1906–07. It was closed at the end of 1944 because other stations in the area could provide cover with their newer motor lifeboats. The boat house was then used as a club, but was washed away in the flood of 15 August 1952. It has since been rebuilt, and now includes a public shelter.[3]

At 7:52 pm on 12 January 1899, the 1,900 ton three-masted ship Forrest Hall, carrying thirteen crew and five apprentices, was in trouble off Porlock Weir on the north Somerset coast, owing to a severe gale that had been blowing all day. She had been under tow, but the tow rope had broken. She was dragging her anchor and had lost her steering gear. The ship's destruction was probable. The alarm was raised for the Louisa, the Lynmouth lifeboat, to be launched to assist. However, launching was impossible because of the terrible weather. Jack Crocombe, the coxswain of the Louisa, proposed to take the boat by road to Porlock's sheltered harbour, 13 miles (21 km) around the coast, and launch it from there.

The boat plus its carriage weighed about 10 tons, and transporting it would not be easy. 20 horses and 100 men started by hauling the boat up the 1 in 4 Countisbury Hill out of Lynmouth. Six of the men were sent ahead with picks and shovels to widen the road. The highest point is 1,423 feet (434 m) above sea level. After they had crossed the 15 miles (24 km) of wild Exmoor paths, they had to descend the dangerous Porlock Hill, with horses and men pulling ropes to stall the descent. During this, they had to demolish part of a garden wall and fell a large tree to make a way. The lifeboat reached Porlock Weir at 6:30 am, and was launched. Although cold, wet, hungry and exhausted, the crew rowed for over an hour in heavy seas to reach the stricken Forrest Hall and rescue the thirteen men and five apprentices with no casualties. However, four of the horses employed died of exhaustion. The Forrest Hall was towed into Barry, Wales.

The feat was immortalised in C Walter Hodges' 1969 children's historical novel The Overland Launch, and was re-enacted 100 years after the event, in daylight, on today's much better roads.

1952 Lynmouth flood

On 15 and 16 August 1952, a storm of tropical intensity broke over South West England, depositing 229 millimetres (9.0 in) of rain within 24 hours on an already waterlogged Exmoor. It is thought that a cold front scooped up a thunderstorm, and the orographic effect worsened the storm. Debris-laden floodwaters cascaded down the northern escarpment of the moor, converging upon the village of Lynmouth. In particular, in the upper West Lyn valley, a dam was formed by fallen trees and other debris; this in due course gave way, sending a huge wave of water and debris down that river. The River Lyn through the town had been culverted in order to gain land for business premises; this culvert soon choked with flood debris, and the river flowed through the town. Much of the debris was boulders and trees.

Overnight, over 100 buildings were destroyed or seriously damaged along with 28 of the 31 bridges, and 38 cars were washed out to sea. In total, 34 people died and a further 420 were made homeless.

Similar events had been recorded at Lynmouth in 1607 and 1796. After the 1952 disaster, the village was rebuilt, including diverting the river around the village.

A conspiracy theory has circulated that the 1952 flood was caused by secret cloud seeding experiments conducted by the RAF.[4][5][6] The theory has been dismissed as "preposterous" by experts.[7]

The small group of houses on the bank of the East Lyn River called Middleham, between Lynmouth and Watersmeet, was destroyed and never rebuilt. Today, a memorial garden stands on the site.

A memorial hall dedicated to the disaster is on the front toward the harbour; it contains photographs, newspaper reports and a scale model of the village, showing how it looked before the flood. A further photo and information display is found in St John the Baptist parish church.

.jpg)

Twinning

The town of Lynton and Lynmouth is twinned with Bénouville in France.

Cultural references

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

In her poem Linmouth, Letitia Elizabeth Landon describes the beauties of rural nature but ends with the words: 'Aye beautiful the dreaming brought By valleys and green fields; But deeper feeling, higher thought, Is what the city yields.' and in the footnote she speaks of her great love for London. Another of her poems, on a different vein, is ![]()

The British technical modern rock band InMe make recurring references to the Lynton/Lynmouth area in their lyrical material. Lynton is mentioned in "In Loving Memory" on their third album Daydream Anonymous, and Lynmouth is mentioned in "Saccharine Arcadia" on Phoenix: The Very Best of InMe. Lead singer Dave McPherson also has a song entitled "Sunny Lynton" on his EP Crescent Summer Sessions and refers to Watersmeet in "Waltzing in a Supermarket" on I Don't Do Requests.

The village of Hollow Bay in The Secret of Crickley Hall by James Herbert is based on Lynmouth; Devil's Cleave is based on the East Lyn Valley and Watersmeet. The book brings together two stories, that of child evacuees during the Second World War and that of the 1952 flood disaster that devastated Lynmouth.

Transport

Lynmouth is served by the following bus services:

- 309/310 Lynton & Lynmouth - Barnstaple (Filers)

See also

- List of natural disasters in the United Kingdom

- Lynton

- Myrtlebury

Notes

- Location of Sillery Sands Beach 51°13′57″N 3°48′24″W

- Sugden, R (6 June 2016). "7 ways to be naked in Bristol this summer". Bristol Post. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- Tomalin, Claire (2005). Young Bysshe. Penguin Books. pp.38-41.

- Leach, Nicholas (2009). Devon's Lifeboat Heritage. Chacewater: Twelveheads Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0-906294-72-7.

- Hilary Bradt; Janice Booth (11 May 2010). Slow Devon and Exmoor. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-84162-322-1.

- "Rain-making link to killer floods". BBC News. 30 August 2001. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

- Vidal, John (30 August 2001). "RAF rainmakers 'caused 1952 flood'". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- The day they made it rain, Philip Eden, WeatherOnline

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Lynton and Lynmouth. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lynmouth. |

- Lynton and Lynmouth at Curlie

- The Lynmouth Flood of 1952 – Exmoor National Park Authority account

- Possible connections with cloud seeding (BBC News, 30 August 2001)

- On this day 16 August 1952 (BBC News)

- Lynmouth Foreland Lighthouse