Battle of Buttington

The Battle of Buttington was fought in 893[lower-alpha 1] between a Viking army and an alliance of Anglo-Saxons and Welsh.

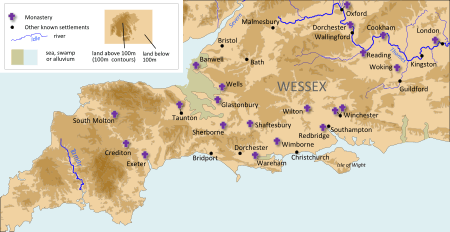

The annals for 893 reported that a large Viking army had landed in the Lympne Estuary, Kent and a smaller force had landed in the Thames estuary under the command of Danish king Hastein. These were reinforced by ships from the settled Danes of East Anglia and Northumbria, some of this contingent sailed round the coast to besiege a fortified place (known as a burh) and Exeter, both in Devon. The English king Alfred the Great, on hearing of Exeter's demise, led all his mounted men to relieve the city. He left his son-in-law Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians and ealdormen Æthelhelm, Æthelnoth, and others in charge of defending various towns and cities from the rest of the Viking army.

The king's thegns managed to assemble a great army consisting of both Saxons and Welsh. The combined army laid siege to the Vikings who had built a fortification at Buttington. After several weeks the starving Vikings broke out of their fortification only to be beaten by the combined English and Welsh army with many of the Vikings being put to flight.

Background

Viking[lower-alpha 2] raids began in England in the late 8th century.[2][3] The raiding continued on and off until the 860s, when instead of raiding the Viking changed their tactics and sent a great army to invade England. This army was described by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as a "Great Heathen Army".[4][5] Alfred defeated the Great Heathen Army at the Battle of Edington in 878. A treaty followed whereby Alfred ceded an enlarged East Anglia to the Danes.[6]

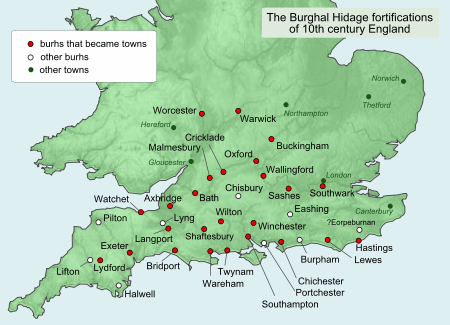

After Edington, Alfred reorganised the defences of Wessex, he built a navy and a standing army. He also built a series of fortified towns, known as burhs[lower-alpha 3] that ringed Wessex. To maintain the burhs, and the standing army, he set up a taxation system known as the Burghal Hidage. Viking raids still continued but his defences made it difficult for the Vikings to make progress. As the political system in Francia (part of modern day France) was in turmoil the Vikings concentrated their efforts there as the raiding was more profitable.[8][9][10]

By late 892 the leadership in Francia had become more stable and the Vikings were finding it difficult to make progress there too, so they again attempted a conquest of England.[11] In 893 two hundred and fifty ships[lower-alpha 4] landed an army in the Lympne Estuary[lower-alpha 5] in Kent where they built a fortification at Appledore. A smaller force of eighty ships under Hastein landed in the Thames estuary before entrenching themselves at Milton, also in Kent.[9] The invaders brought their wives and children with them, indicating a meaningful attempt at conquest and colonisation. Alfred took up a position from which he could observe both of the Viking armies.[13] The Vikings were further reinforced with 240 ships, that were provided by the Danes of East Anglia and Northumbria who had settled there after the wars of the 860s and 870s. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that they did it "contrary to [their] pledges."[lower-alpha 6][15][16]

At some point Alfred's army captured Hastein's family.[15] The annals report that Alfred was in talks with Hastein, but do not say why. Horspool speculates that it may well be to do with Hastein's family, however while the talks were going on, the Danes at Appledore broke out and struck northwestwards.[9][15] They were overtaken by Alfred's eldest son, Edward, and were defeated in a general engagement at Farnham in Surrey. They took refuge on an island at Thorney, on Hertfordshire's River Colne, where they were blockaded and were ultimately forced to submit.[13] The force fell back on Essex and, after suffering another defeat at Benfleet, joined Hastein's army at Shoebury.[9][15]

Alfred had been on his way to relieve his son at Thorney when he heard that the Northumbrian and East Anglian Danes were besieging Exeter and an unnamed[lower-alpha 7] burh on the North Devon shore. Alfred at once hurried westward and when he arrived at Exeter, the Danes took to their ships. The siege of Exeter was lifted but the fate of the unnamed North Devon burh is not recorded. Meanwhile, the force under Hastein set out to march up the Thames Valley, possibly with the idea of assisting their friends in the west.[lower-alpha 8] But they were met by the Western army that consisted of West Saxons, Mercians, and some Welsh, it was led by three eldermen namely Æthelred the Lord of the Mercians, Æthelhelm the Ealdorman of Wiltshire, and Æthelnoth the Ealdorman of Somerset. The chronicle says that they "were drawn from every burh east of the Parret; both west and east of Selwood, also north of the Thames and west of the Severn as well as some part of the Welsh people".[lower-alpha 9][4] Æthelred, although a Mercian, was married to Alfred's daughter and thus as his son in law was able to cross the borders of Wessex in pursuit of Vikings. The combined Anglo-Saxon and Welsh army forced the Vikings to the northwest, where they were finally overtaken and besieged at Buttington.[9]

Siege and battle

The English and Welsh army came up the River Severn, and besieged all sides of the fortification (at Buttington) where the Vikings had taken refuge. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that "after many weeks had passed, some of the heathen [Vikings] died of hunger, but some, having by then eaten their horses, broke out of the fortress, and joined battle with those who were on the east bank of the river. But, when many thousands of pagans had been slain, and all the others had been put to flight, the Christians [English and Welsh] were masters of the place of death. In that battle, the most noble Ordheah and many of the king's thegns were killed."[9][15]

Location of the battle

The annals say that the Vikings came up the Severn from the Thames making the most likely candidate for the location of the battle as present-day Buttington,[18] Welshpool in the county of Powys, Wales. Another place that has been suggested is Buttington Tump at the mouth of the River Wye, where it flows into the Severn but this is seen as less likely.[19]

Aftermath

The Vikings who had taken to their ships after Alfred's arrival, at Exeter, sailed along the south coast and attempted to raid Chichester, a burh according to the Burghal Hidage, manned by 1,500 men. The chronicle says that the citizens "put many [Vikings] to flight and killed hundreds of them and captured some of their ships".[15]

According to the Anglo-Saxon historian Æthelweard writing nearly a hundred years later, "Hastein made a rush with a large force from Benfleet, and ravaged savagely through all the lands of the Mercians, until he and his men reached the borders of the Welsh; the army stationed then in the east of the country gave them support, and the Northumbrian one similarly. The famous Ealdorman Æthelhelm made open preparation with a cavalry force, and gave pursuit together with the western English army under the generalship of Æthelnoth. And King (sic) Æthelred of the Mercians was afterwards present with them, being at hand with a large army."[20]

The Buttington Oak was said to have been planted by local people to commemorate the battle and survived until February 2018.[21]

Notes

- The Anglo Saxon Chronicle MSS A and Æthelweard have the year as 893. MSS B, C, D and John of Worcester 894

- The word viking is a historical revival; it was not used in Middle English, but it was revived from Old Norse vikingr "freebooter, sea-rover, pirate, viking," which usually is explained as meaning properly "one who came from the fjords," from vik "creek, inlet, small bay" (cf. Old English wic, Middle High German wich "bay," and second element in Reykjavik). But Old English wicing and Old Frisian wizing are almost 300 years older, and probably derive from wic "village, camp" (temporary camps were a feature of the Viking raids), related to Latin vicus "village, habitation"[1]

- Burh does not mean fortified town per se. Anglo Saxons used the word to denote any place within a boundary which could include private fortifications or simply a place with a hedge or fence round it.[7]

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 893 MSS A, E and F said there were 250 ships and MSS B, C and D suggest 200.

- The Limen is the old name for the River Rother that existed till the 16th century. It rises near Rotherfield, Sussex and in Saxon times flowed north of the Isle of Oxney, then past Appledore into the sea near Lympne and Hythe.[12]

- John of Worcester claims that East Anglian and Northumbrian fleet contained about 140 ships.[14]

- The fortification was possibly Pilton as named in the Burghal Hidage.[17]

- The Anglo Saxon Chronicle MSS A talks about two Viking fleets, one attacking Exeter, the other attacking the north coast of Devon, other versions of this annal suggest that a fleet divided in two before making the attacks. John of Worcester says that 140 were involved in these two attacks whereas MSS A suggests 100.[14]

- For the relationship with Wales during Alfred's reign, see Assers Life of Alfred Chapters 80-81

Citations

- "Viking". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- Sawyer. The Oxford Illustrated History of Vikings. pp. 2–3

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 793 – English translation at project Gutenberg. Retrieved 4 August 2014

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 865 – English translation at project Gutenberg. Retrieved 4 August 2014

- Oliver. Vikings. A History. p. 169

- Attenborough, F.L. Tr., ed. (1922). The laws of the earliest English kings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–101. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- Lavelle. Fortifications in Wessex. p. 4

- P. H. Sawyer, Kings and Vikings: Scandinavia and Europe, A.D. 700-1100 (London: Routledge, 1989),p. 91, https://www.questia.com/read/105571409

- Horspool. Why Alfred Burnt the Cakes. pp. 104-110

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 896, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 897. English translation at Project Gutenberg Retrieved 4 August 2014

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 892 – English translation at project Gutenberg. Retrieved 4 August 2014

- Chantler. Rother Country. Ch. 1

- Merkle. The White Horse King: The Life of Alfred the Great. p. 220

- John of Worcester, The Chronicle of John of Worcester, ed. R. R. Darlington and P. McGurk, trans. Jennifer Bray (New York: Clarendon Press, 1995), p. 341, https://www.questia.com/read/98726313.

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle 893 – English translation at project Gutenberg. Retrieved 4 August 2014

- John of Worcester, The Chronicle of John of Worcester, ed. R. R. Darlington and P. McGurk, trans. Jennifer Bray (New York: Clarendon Press, 1995), p. 345, https://www.questia.com/read/98726313.

- Keynes/ Lapidge. Alfred the Great. p. 115 and p. 287 fn. 9

- "Buttington, Possible site of battle near Welshpool". Royal Commission on Historic Sites in Wales.

- Keynes/ Lapidge. Alfred the Great. p. 267 Note 16

- Ethelwerd. Ethelwerd's Chronicle. Ch.III. 893

- "1,000-year-old oak on Offa's Dyke falls". BBC News. 16 February 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

References

- Chantler, Bob (2010). Rother Country: a Short History and Guide to the River Rother in East Sussex, and the Towns and Villages near to the River. Bob Chantler. GGKEY:RD76BJL3758. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- Ethelwerd (1848). Giles, J.A. (ed.). Ethelwerd's Chronicle. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Higham, N.J; Ryan, Martin J, eds. (2011). Place-names, Language and the Anglo-Saxon Landscape. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-603-2.

- Horspool, David (2006). Why Alfred Burned the Cakes. London: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-86197-786-1.

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (1983). Alfred the Great, Asser's Life of King Alfred and other contemporary sources. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044409-2.

- John of Worcester (1995). Darlington, R. R.; McGurk, P.P.; Bray tr., Jennifer (eds.). The Chronicle of John of Worcester. New York: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822261-0.

- Lavelle, Ryan (2003). Fortifications in Wessex c. 800-1016. Botley, Oxfordshire: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-639-9.

- Lavelle, Ryan (2010). Alfred's Wars Sources and Interpretations of Anglo-Saxon Warfare in the Viking Age. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydel Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-569-1.

- Merkle, Benjamin (2009). The White Horse King: The Life of Alfred the Great. Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson. ISBN 1-5955-5252-9.

- Oliver, Neil (2012). Vikings. A History. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-86787-6.

- Sawyer, Peter (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings (3rd ed.). Oxford: OUP. ISBN 0-19-285434-8.

- Sawyer, Peter (1989). Kings and Vikings: Scandinavia and Europe, A.D. 700-1100. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-04590-8.