Ajam

Ajam (عجم) is an Arabic word meaning mute, which today refers to someone whose mother tongue is not Arabic. During the Arab conquest of Persia, the term became a racial pejorative.[1]

Etymology

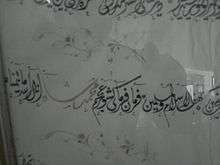

According to traditional etymology, the word ʿajam comes from the Semitic root aʿ-j-m. Related forms of the same root include, but are not limited to:[2]

- mustaʿjim: mute, incapable of speech

- ʿajama / ʾaʿjama / ʿajjama: to dot – in particular, to add the dots that distinguish between various Arabic letters to a text (and hence make it easier for a non-native Arabic speaker to read). It is now an obsolete term, since all modern Arabic texts are dotted. This may also be linked to ʿajām / ʿajam "pit, seed (e.g. of a date or grape)".

- inʿajama: (of speech) to be incomprehensible

- istaʿjama: to fall silent; to be unable to speak

- 'aʿjam: non-fluent

Homophonous words, which may or may not be derived from the same root, include:

- ʿajama: to test (a person); to try (a food).

Modern use of "ajam" has the meaning of "non-Arab".[3]

Original meaning

The verb ʿajama originally meant "to mumble, and speak indistinctly", which is the opposite of ʿaraba, “to speak clearly”. Accordingly, the noun ʿujma, of the same root, is the opposite of fuṣḥa, which means "chaste, correct, Arabic language".[4] In general, during the Umayyad period ajam was a pejorative term used by Arabs who believed in their social and political superiority, in early history after Islam. However, the distinction between Arab and Ajam is discernible in pre-Islamic poetry.[4]

Pejorative use

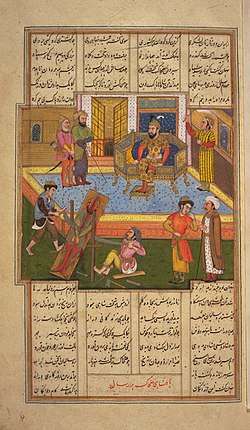

During the Umayyad period, the term developed a derogatory meaning as the word was used to refer to non-Arab speakers (primarily Persians) as illiterate and uneducated. Arab conquerors in that period tried to impose Arabic as the primary language of the subject peoples throughout their empire. Angry with the prevalence of the Persian language in the Divan and Persian society, Persian resistance to this mentality was popularised in the final verse of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh; this verse is widely regarded by Iranians as the primary reason that they speak Persian and not Arabic to this day.[5] Under the Umayyad dynasty, official association with the Arab dominion was only given to those with the ethnic identity of the Arab and required formal association with an Arab tribe and the adoption of the client status (mawālī, another derogatory term translated to mean "slave" or "lesser" in this context).[6] The pejorative use to denote Persians as "Ajam" is so ingrained in the Arab world that it is colloquially used to refer to Persians as "Ajam" neglecting the original definition and etymology of the word.

Colloquial use

According to Clifford Edmund Bosworth, "by the 3rd/9th century, the non-Arabs, and above all the Persians, were asserting their social and cultural equality (taswīa) with the Arabs, if not their superiority (tafżīl) over them (a process seen in the literary movement of the Šoʿūbīya). In any case, there was always in some minds a current of admiration for the ʿAǰam as heirs of an ancient, cultured tradition of life. After these controversies had died down, and the Persians had achieved a position of power in the Islamic world comparable to their numbers and capabilities, "ʿAjam" became a simple ethnic and geographical designation.".[7] Thus by the ninth century, the term was being used by Persians themselves as an ethnic term, and examples can be given by Asadi Tusi in his poem comparing the superiority of Persians and Arabs.[8] Accordingly: "territorial notions of “Iran,” are reflected in such terms as irānšahr, irānzamin, or Faris, the Arabicized form of Pārs/Fārs (Persia). The ethnic notion of “Iranian” is denoted by the Persian words Pārsi or Irāni, and the Arabic term Ahl Faris (inhabitants of Persia) or ʿAjam, referring to non-Arabs, but primarily to Persians as in molk-e ʿAjam (Persian kingdom) or moluk-e ʿAjam (Persian kings).".[9]

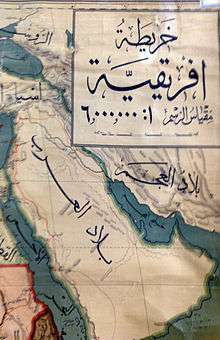

According to The Political Language of Islam, during the Islamic Golden Age, 'Ajam' was used colloquially as a reference to denote those whom Arabs in the Arabian Peninsula viewed as "alien" or outsiders.[10] The early application of the term included all of the non-Arab peoples with whom the Arabs had contact including Persians, Byzantine Greeks, Ethiopians, Armenians, Assyrians, Mandaeans, Arameans, Jews, Georgians, Sabians, Samaritans, Egyptians, and Berbers.

During the early age of the Caliphates, Ajam was often synonymous with "foreigner" or "stranger". In the Western Asia, it was generally applied to the Persians, while in al-Andalus it referred to speakers of Romance languages - becoming "Aljamiado" in Spanish in reference to Arabic-script writing of those languages - and in West Africa refers to the Ajami script or the writing of local languages such as Hausa and Fulani in the Arabic alphabet. In Zanzibar ajami and ajamo means Persian which came from the Persian Gulf and the cities of Shiraz and Siraf. In Turkish, there are many documents and letters that used Ajam to refer to Persian.

In the Persian Gulf region today, people still refer to Persians as Ajami, referring to Persian carpets as sajjad al Ajami (Ajami carpet), Persian cat as Ajami cats, and Persian Kings as Ajami kings.[11]

Notable examples

- The Persian community in Bahrain is called Ajami.

- 'Ajam was used by the Ottomans to refer to the Safavid dynasty.[12]

- The Abbasid Iraq Al-Ajam province (centered around Arax and Shirvan).

- The Kurdish historian, Sharaf Khan Bidlisi, uses the term Ajam in his book Sharafnama (1597 CE) to refer to the Shia Persians.[13]

- In the Eastern Anatolia Region, Azerbaijanis are sometimes referred to as acem (which is the Turkish translation of Ajam).[14]

- Although claimed otherwise by Mahmood Reza Ghods, Modern Sunni Kurds of Iran do not use this term to denote Persians, Azeris and Southern Kurds.[15] According to Sharhzad Mojab, Ecem (derived from the Arabic ‘ajam) is used by Kurds to refer to Persians and, sometimes, Turks.[16]

- Adjam, Hajjam, Ajaim, Ajami, Akham (as Axam in Spain for ajam), Ayam in Europe.

- In Turkish, the word acem refers to Iran and Iranian people.[17]

- It is also used as a surname.[18]

- In Arab music, there is a maqam (musical mode) called Ajam, pejoratively translated to "the Persian mode", corresponding to the major scale in European music.[19]

See also

- Ajami (disambiguation)

- Barbarian

- Nemets - the name given to Germany or the German people in many Slavic languages, with a similar derivation to Ajam

- Ajam of Bahrain

- Ajam of Iraq

- Ajam of Kuwait

References

- Frye, Richard Nelson; Zarrinkoub, Abdolhosein (1975). "Section on The Arab Conquest of Iran". Cambridge History of Iran. London. 4: 46.

- "Sakhr: Lisan al-Arab". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- "Sakhr: Multilingual Dictionary". Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- Encyclopædia Iranica, "Ajam, p.700 Archived 2007-12-15 at the Wayback Machine"

- Firdawsī; Davis, Dick (2006). Shahnameh: the Persian Book of Kings. New York: Viking.

- Astren, Fred (February 1, 2004). Karaite Judaism and Historical Understanding. Univ of South Carolina Press. pp. 33–35. ISBN 1-57003-518-0.

- Encyclopædia Iranica, "Ajam", Bosworth

-

گفتمش چو دیوانه بسی گفتی و اکنون

پاسخ شنو ای بوده چون دیوان بیابان

عیب ار چه کنی اهل گرانمایه عجم را

چه بوید شما خود گلهء غر شتربان

Jalal Khaleqi Motlaq, "Asadi Tusi", Majaleyeh Daneshkadeyeh Adabiyaat o Olum-e Insani(Literature and Humanities Magazine), Ferdowsi University, 1357(1978). page 71. - Encyclopedia Iranica, "IRANIAN IDENTITY iii. MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC PERIOD" by Ahmad Ashraf

- Lewis, Bernard (11 June 1991). "The Political Language of Islam". University Of Chicago Press. Retrieved 6 February 2017 – via Amazon.

- The Book.documents on the Persian gulf's name.names of Iran Archived 2011-04-03 at the Wayback Machine pp.23-60 Molk e Ajam= Persi . Molk-e-Jam and Molouk -e-Ajam(Persian Kings). عجم تهران 2010 ISBN 978-600-90231-4-1

- Martin van Bruinessen. "Nationalisme kurde et ethnicités intra-kurdes", Peuples Méditerranéens no. 68-69 (1994), 11-37.

- Philip G. Kreyenbroek, Stefan Sperl, The Kurds, 250 pp., Routledge, 1992, ISBN 978-0-415-07265-6 (see p.38)

- (in Turkish) Qarslı bir azərbaycanlının ürək sözləri. Erol Özaydın

- Mahmood Reza Ghods, A comparative historical study of the causes, development and effects of the revolutionary movements in northern Iran in 1920-21 and 1945-46. University of Denver, 1988. v.1, p.75.

- Mojab, Shahrzad (Summer 2015). "Deçmewe Sablax [Going Back to Sablagh] by Shilan Hasanpour (review)". The Middle East Journal. 69: 488–489.

- "Turkish Language Association: Acem".

- "Names Database: Ajam Surname". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- A. J. Racy, "Making Music in the Arab World", Published by Cambridge University Press, 2004. pg 110.