Aikido

Aikido (合気道, aikidō, Japanese pronunciation: [aikiꜜdoː], kyūjitai: 合氣道) is a modern Japanese martial art developed by Morihei Ueshiba as a synthesis of his martial studies, philosophy and religious beliefs. Ueshiba's goal was to create an art that practitioners could use to defend themselves while also protecting their attackers from injury.[1][2] Aikido is often translated as "the way of unifying (with) life energy"[3] or as "the way of harmonious spirit".[4] According to the founder's philosophy, the primary goal in the practice of aikido is to overcome oneself instead of cultivating violence or aggressiveness.[5] Morihei Ueshiba used the phrase "masakatsu agatsu katsuhayabi" (Japanese: 正勝吾勝勝速日) ("true victory, final victory over oneself, here and now") to refer to this principle.[6]

A version of the "four-direction throw" (shihōnage) with standing attacker and seated defender. | |

| Focus | Grappling and softness |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Japan |

| Creator | Morihei Ueshiba |

| Famous practitioners | Kisshomaru Ueshiba, Moriteru Ueshiba, Christian Tissier, Morihiro Saito, Koichi Tohei, Yoshimitsu Yamada, Gozo Shioda, Mitsugi Saotome, Steven Seagal |

| Ancestor arts | Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu |

Aikido's fundamental principles include: irimi[7] (entering), atemi,[8][9] kokyu-ho (breathing control), sankaku-ho (triangular principle) and tenkan (turning) movements that redirect the opponent's attack momentum. Its curriculum comprises various techniques, primarily throws and joint locks.[10] It also includes a weapons system encompassing the bokken, tantō and jō.

Aikido derives mainly from the martial art of Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu, but began to diverge from it in the late 1920s, partly due to Ueshiba's involvement with the Ōmoto-kyō religion. Ueshiba's early students' documents bear the term aiki-jūjutsu.[11]

Ueshiba's senior students have different approaches to aikido, depending partly on when they studied with him. Today, aikido is found all over the world in a number of styles, with broad ranges of interpretation and emphasis. However, they all share techniques formulated by Ueshiba and most have concern for the well-being of the attacker.

Etymology and basic philosophy

The word "aikido" is formed of three kanji:

- 合 – ai – joining, unifying, combining, fitting

- 気 – ki – spirit, energy, mood, morale

- 道 – dō – way, path

The term aiki does not readily appear in the Japanese language outside the scope of budō. This has led to many possible interpretations of the word. 合 is mainly used in compounds to mean 'combine, unite, join together, meet', examples being 合同 (combined/united), 合成 (composition), 結合 (unite/combine/join together), 連合 (union/alliance/association), 統合 (combine/unify), and 合意 (mutual agreement). There is an idea of reciprocity, 知り合う (to get to know one another), 話し合い (talk/discussion/negotiation), and 待ち合わせる (meet by appointment).

気 is often used to describe a feeling, as in X気がする ('I feel X', as in terms of thinking but with less cognitive reasoning), and 気持ち (feeling/sensation); it is used to mean energy or force, as in 電気 (electricity) and 磁気 (magnetism); it can also refer to qualities or aspects of people or things, as in 気質 (spirit/trait/temperament).

The term dō is also found in martial arts such as judo and kendo, and in various non-martial arts, such as Japanese calligraphy (shodō), flower arranging (kadō) and tea ceremony (chadō or sadō).

Therefore, from a purely literal interpretation, aikido is the "Way of combining forces" or "Way of unifying energy", in which the term aiki refers to the martial arts principle or tactic of blending with an attacker's movements for the purpose of controlling their actions with minimal effort.[12] One applies aiki by understanding the rhythm and intent of the attacker to find the optimal position and timing to apply a counter-technique.

History

Aikido was created by Morihei Ueshiba (植芝 盛平 Ueshiba Morihei, 1883–1969), referred to by some aikido practitioners as Ōsensei (Great Teacher).[13] The term aikido was coined in the twentieth century.[14] Ueshiba envisioned aikido not only as the synthesis of his martial training, but as an expression of his personal philosophy of universal peace and reconciliation. During Ueshiba's lifetime and continuing today, aikido has evolved from the aiki that Ueshiba studied into a variety of expressions by martial artists throughout the world.[10]

Initial development

Ueshiba developed aikido primarily during the late 1920s through the 1930s through the synthesis of the older martial arts that he had studied.[15] The core martial art from which aikido derives is Daitō-ryū aiki-jūjutsu, which Ueshiba studied directly with Takeda Sōkaku, the reviver of that art. Additionally, Ueshiba is known to have studied Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū with Tozawa Tokusaburō in Tokyo in 1901, Gotōha Yagyū Shingan-ryū under Nakai Masakatsu in Sakai from 1903 to 1908, and judo with Kiyoichi Takagi (高木 喜代市 Takagi Kiyoichi, 1894–1972) in Tanabe in 1911.[16]

The art of Daitō-ryū is the primary technical influence on aikido. Along with empty-handed throwing and joint-locking techniques, Ueshiba incorporated training movements with weapons, such as those for the spear (yari), short staff (jō), and possibly the bayonet (銃剣, jūken). Aikido also derives much of its technical structure from the art of swordsmanship (kenjutsu).[4][17]

Ueshiba moved to Hokkaidō in 1912, and began studying under Takeda Sokaku in 1915; His official association with Daitō-ryū continued until 1937.[15] However, during the latter part of that period, Ueshiba had already begun to distance himself from Takeda and the Daitō-ryū. At that time Ueshiba referred to his martial art as "Aiki Budō". It is unclear exactly when Ueshiba began using the name "aikido", but it became the official name of the art in 1942 when the Greater Japan Martial Virtue Society (Dai Nippon Butoku Kai) was engaged in a government sponsored reorganization and centralization of Japanese martial arts.[10]

Religious influences

After Ueshiba left Hokkaidō in 1919, he met and was profoundly influenced by Onisaburo Deguchi, the spiritual leader of the Ōmoto-kyō religion (a neo-Shinto movement) in Ayabe.[18] One of the primary features of Ōmoto-kyō is its emphasis on the attainment of utopia during one's life. This idea was a great influence on Ueshiba's martial arts philosophy of extending love and compassion especially to those who seek to harm others. Aikido demonstrates this philosophy in its emphasis on mastering martial arts so that one may receive an attack and harmlessly redirect it. In an ideal resolution, not only is the receiver unharmed, but so is the attacker.[19]

In addition to the effect on his spiritual growth, the connection with Deguchi gave Ueshiba entry to elite political and military circles as a martial artist. As a result of this exposure, he was able to attract not only financial backing but also gifted students. Several of these students would found their own styles of aikido.[20]

International dissemination

Aikido was first introduced to the rest of the world in 1951 by Minoru Mochizuki with a visit to France, where he demonstrated aikido techniques to judo students.[21] He was followed by Tadashi Abe in 1952, who came as the official Aikikai Hombu representative, remaining in France for seven years. Kenji Tomiki toured with a delegation of various martial arts through 15 continental states of the United States in 1953.[20][22] Later that year, Koichi Tohei was sent by Aikikai Hombu to Hawaii for a full year, where he set up several dōjō. This trip was followed by several subsequent visits and is considered the formal introduction of aikido to the United States. The United Kingdom followed in 1955; Italy in 1964 by Hiroshi Tada; and Germany in 1965 by Katsuaki Asai. Designated the "Official Delegate for Europe and Africa" by Morihei Ueshiba, Masamichi Noro arrived in France in September 1961. Seiichi Sugano was appointed to introduce aikido to Australia in 1965. Today there are aikido dōjō throughout the world.

Proliferation of independent organizations

The largest aikido organization is the Aikikai Foundation, which remains under the control of the Ueshiba family. However, aikido has developed into many styles, most of which were formed by Morihei Ueshiba's major students.[20]

The earliest independent styles to emerge were Yoseikan Aikido, begun by Minoru Mochizuki in 1931,[21] Yoshinkan Aikido, founded by Gozo Shioda in 1955,[23] and Shodokan Aikido, founded by Kenji Tomiki in 1967.[24] The emergence of these styles pre-dated Ueshiba's death and did not cause any major upheavals when they were formalized. Shodokan Aikido, however, was controversial, since it introduced a unique rule-based competition that some felt was contrary to the spirit of aikido.[20]

After Ueshiba's death in 1969, two more major styles emerged. Significant controversy arose with the departure of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo's chief instructor Koichi Tohei, in 1974. Tohei left as a result of a disagreement with the son of the founder, Kisshomaru Ueshiba, who at that time headed the Aikikai Foundation. The disagreement was over the proper role of ki development in regular aikido training. After Tohei left, he formed his own style, called Shin Shin Toitsu Aikido, and the organization that governs it, the Ki Society (Ki no Kenkyūkai).[25]

A final major style evolved from Ueshiba's retirement in Iwama, Ibaraki and the teaching methodology of long term student Morihiro Saito. It is unofficially referred to as the "Iwama style", and at one point a number of its followers formed a loose network of schools they called Iwama Ryu. Although Iwama style practitioners remained part of the Aikikai until Saito's death in 2002, followers of Saito subsequently split into two groups. One remained with the Aikikai and the other formed the independent Shinshin Aikishuren Kai in 2004 around Saito's son Hitohiro Saito.

Today, the major styles of aikido are each run by a separate governing organization, have their own headquarters (本部道場, honbu dōjō) in Japan, and are taught throughout the world.[20]

Ki

The study of ki is an important component of aikido. The term does not specifically refer to either physical or mental training, as it encompasses both. The kanji for ki normally is written as 気. It was written as 氣 until the writing reforms after World War II, and this older form still is seen on occasion.

The character for ki is used in everyday Japanese terms, such as "health" (元気, genki), or "shyness" (内気, uchiki). Ki has many meanings, including "ambience", "mind", "mood", and "intention", however, in traditional martial arts it is often used to refer to "life energy". Gōzō Shioda's Yoshinkan Aikido, considered one of the "hard styles", largely follows Ueshiba's teachings from before World War II, and surmises that the secret to ki lies in timing and the application of the whole body's strength to a single point.[26] In later years, Ueshiba's application of ki in aikido took on a softer, more gentle feel. This concept was known as Takemusu Aiki, and many of his later students teach about ki from this perspective. Koichi Tohei's Ki Society centers almost exclusively around the study of the empirical (albeit subjective) experience of ki, with students' proficiency in aikido techniques and ki development ranked separately.[27]

Training

In aikido, as in virtually all Japanese martial arts, there are both physical and mental aspects of training. The physical training in aikido is diverse, covering both general physical fitness and conditioning, as well as specific techniques.[28] Because a substantial portion of any aikido curriculum consists of throws, beginners learn how to safely fall or roll.[28] The specific techniques for attack include both strikes and grabs; the techniques for defense consist of throws and pins. After basic techniques are learned, students study freestyle defense against multiple opponents, and techniques with weapons.

Fitness

Physical training goals pursued in conjunction with aikido include controlled relaxation, correct movement of joints such as hips and shoulders, flexibility, and endurance, with less emphasis on strength training. In aikido, pushing or extending movements are much more common than pulling or contracting movements. This distinction can be applied to general fitness goals for the aikido practitioner.[4]

In aikido, specific muscles or muscle groups are not isolated and worked to improve tone, mass, or power. Aikido-related training emphasizes the use of coordinated whole-body movement and balance similar to yoga or pilates. For example, many dōjōs begin each class with warm-up exercises (準備体操, junbi taisō), which may include stretching and ukemi (break falls).[29]

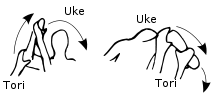

Roles of uke and tori

Aikido training is based primarily on two partners practicing pre-arranged forms (kata) rather than freestyle practice. The basic pattern is for the receiver of the technique (uke) to initiate an attack against the person who applies the technique—the 取り tori, or shite 仕手 (depending on aikido style), also referred to as 投げ nage (when applying a throwing technique), who neutralises this attack with an aikido technique.[30]

Both halves of the technique, that of uke and that of tori, are considered essential to aikido training.[30] Both are studying aikido principles of blending and adaptation. Tori learns to blend with and control attacking energy, while uke learns to become calm and flexible in the disadvantageous, off-balance positions in which tori places them. This "receiving" of the technique is called ukemi.[30] Uke continuously seeks to regain balance and cover vulnerabilities (e.g., an exposed side), while tori uses position and timing to keep uke off-balance and vulnerable. In more advanced training, uke will sometimes apply reversal techniques (返し技, kaeshi-waza) to regain balance and pin or throw tori.

Ukemi (受身) refers to the act of receiving a technique. Good ukemi involves attention to the technique, the partner, and the immediate environment—it is considered an active part of the process of learning aikido. The method of falling itself is also important, and is a way for the practitioner to receive an aikido technique safely and minimize risk of injury.

Initial attacks

Aikido techniques are usually a defense against an attack, so students must learn to deliver various types of attacks to be able to practice aikido with a partner. Although attacks are not studied as thoroughly as in striking-based arts, attacks with intent (such as a strong strike or an immobilizing grab) are needed to study correct and effective application of technique.[4]

Many of the strikes (打ち, uchi) of aikido resemble cuts from a sword or other grasped object, which indicate its origins in techniques intended for armed combat.[4] Other techniques, which explicitly appear to be punches (tsuki), are practiced as thrusts with a knife or sword. Kicks are generally reserved for upper-level variations; reasons cited include that falls from kicks are especially dangerous, and that kicks (high kicks in particular) were uncommon during the types of combat prevalent in feudal Japan.

Some basic strikes include:

- Front-of-the-head strike (正面打ち, shōmen'uchi) is a vertical knifehand strike to the head. In training, this is usually directed at the forehead or the crown for safety, but more dangerous versions of this attack target the bridge of the nose and the maxillary sinus.

- Side-of-the-head strike (横面打ち, yokomen'uchi) is a diagonal knifehand strike to the side of the head or neck.

- Chest thrust (胸突き, mune-tsuki) is a punch to the torso. Specific targets include the chest, abdomen, and solar plexus, sometimes referred to as "middle-level thrust" (中段突き, chūdan-tsuki), or "direct thrust" (直突き, choku-tsuki).

- Face thrust (顔面突き, ganmen-tsuki) is a punch to the face, sometimes referred to as "upper-level thrust" (上段突き, jōdan-tsuki).

Beginners in particular often practice techniques from grabs, both because they are safer and because it is easier to feel the energy and the direction of the movement of force of a hold than it is for a strike. Some grabs are historically derived from being held while trying to draw a weapon, whereupon a technique could then be used to free oneself and immobilize or strike the attacker while they are grabbing the defender.[4] The following are examples of some basic grabs:

- Single-hand grab (片手取り, katate-dori), when one hand grabs one wrist.

- Both-hands grab (諸手取り, morote-dori), when both hands grab one wrist; sometimes referred to as "single hand double-handed grab" (片手両手取り, katateryōte-dori)

- Both-hands grab (両手取り, ryōte-dori), when both hands grab both wrists; sometimes referred to as "double single-handed grab" (両片手取り, ryōkatate-dori).

- Shoulder grab (肩取り, kata-dori) when one shoulder is grabbed.

- "Both-shoulders-grab (両肩取り, ryōkata-dori), when both shoulders are grabbed. It is sometimes combined with an overhead strike as Shoulder grab face strike (肩取り面打ち, kata-dori men-uchi).

- Chest grab (胸取り, mune-dori or muna-dori), when the lapel is grabbed; sometimes referred to as "collar grab" (襟取り, eri-dori).

Basic techniques

The following are a sample of the basic or widely practiced throws and pins. Many of these techniques derive from Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu, but some others were invented by Morihei Ueshiba. The precise terminology for some may vary between organisations and styles; the following are the terms used by the Aikikai Foundation. Note that despite the names of the first five techniques listed, they are not universally taught in numeric order.[31]

- First technique (一教 (教), ikkyō), a control technique using one hand on the elbow and one hand near the wrist which leverages uke to the ground.[32] This grip applies pressure into the ulnar nerve at the wrist.

- Second technique (二教, nikyō) is a pronating wristlock that torques the arm and applies painful nerve pressure. (There is an adductive wristlock or Z-lock in the ura version.)

- Third technique (三教, sankyō) is a rotational wristlock that directs upward-spiraling tension throughout the arm, elbow and shoulder.

- Fourth technique (四教, yonkyō)is a shoulder control technique similar to ikkyō, but with both hands gripping the forearm. The knuckles (from the palm side) are applied to the recipient's radial nerve against the periosteum of the forearm bone.[33]

- Fifth technique (五教, gokyō)is a technique that is visually similar to ikkyō, but with an inverted grip of the wrist, medial rotation of the arm and shoulder, and downward pressure on the elbow. Common in knife and other weapon take-aways.

- 'Four-direction throw (四方投げ, shihōnage) is a throw during which ukes hand' is folded back past the shoulder, locking the shoulder joint.

- Forearm return (小手返し, kotegaeshi) is a supinating wristlock-throw that stretches the extensor digitorum.

- Breath throw (呼吸投げ, kokyūnage) is a loosely used umbrella term for various types of mechanically unrelated techniques; kokyūnage generally do not use joint locks like other techniques.[34]

- Entering throw (入身投げ, iriminage), throws in which tori moves through the space occupied by uke. The classic form superficially resembles a "clothesline" technique.

- Heaven-and-earth throw (天地投げ, tenchinage), a throw in which, beginning with ryōte-dori, moving forward, tori sweeps one hand low ("earth") and the other high ("heaven"), which unbalances uke so that he or she easily topples over.

- Hip throw (腰投げ, koshinage), aikido's version of the hip throw; tori drops their hips lower than those of uke, then flips uke over the resultant fulcrum.

- Figure-ten throw (十字投げ, jūjinage) or figure-ten entanglement (十字絡み, jūjigarami), a throw that locks the arms against each other (the kanji for "10" is a cross-shape: 十).[35]

- 'Rotary throw (回転投げ, kaitennage) is a throw in which tori sweeps ukes arm back until it locks the shoulder joint, then uses forward pressure to throw them.[36]

Implementations

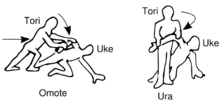

Aikido makes use of body movement (tai sabaki) to blend the movement of tori with the movement of uke. For example, an "entering" (irimi) technique consists of movements inward towards uke, while a "turning" (転換, tenkan) technique uses a pivoting motion.[37] Additionally, an "inside" (内, uchi) technique takes place in front of uke, whereas an "outside" (外, soto) technique takes place to their side; a "front" (表, omote) technique is applied with motion to the front of uke, and a "rear" (裏, ura) version is applied with motion towards the rear of uke, usually by incorporating a turning or pivoting motion. Finally, most techniques can be performed while in a seated posture (seiza). Techniques where both uke and tori are standing are called tachi-waza, techniques where both start off in seiza are called suwari-waza, and techniques performed with uke standing and tori sitting are called hanmi handachi (半身半立).[38]

From these few basic techniques, there are numerous of possible implementations. For example, ikkyō can be applied to an opponent moving forward with a strike (perhaps with an ura type of movement to redirect the incoming force), or to an opponent who has already struck and is now moving back to reestablish distance (perhaps an omote-waza version). Specific aikido kata are typically referred to with the formula "attack-technique(-modifier)"; katate-dori ikkyō, for example, refers to any ikkyō technique executed when uke is holding one wrist. This could be further specified as katate-dori ikkyō omote (referring to any forward-moving ikkyō technique from that grab).

Atemi (当て身) are strikes (or feints) employed during an aikido technique. Some view atemi as attacks against "vital points" meant to cause damage in and of themselves. For instance, Gōzō Shioda described using atemi in a brawl to quickly down a gang's leader.[26] Others consider atemi, especially to the face, to be methods of distraction meant to enable other techniques; a strike, even if it is blocked, can startle the target and break their concentration. Additionally, the target may also become unbalanced while attempting to avoid a strike (by jerking the head back, for example) which may allow for an easier throw.[38] Many sayings about atemi are attributed to Morihei Ueshiba, who considered them an essential element of technique.[39]

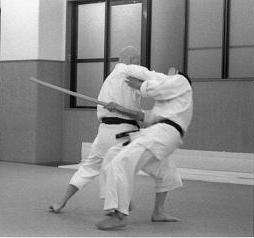

Weapons

Weapons training in aikido traditionally includes the short staff (jō) (these techniques closely resemble the use of the bayonet, or Jūkendō), the wooden sword (bokken), and the knife (tantō).[40] Some schools incorporate firearm-disarming techniques, where either weapon-taking and/or weapon-retention may be taught. Some schools, such as the Iwama style of Morihiro Saito, usually spend substantial time practicing with both bokken and jō, under the names of aiki-ken, and aiki-jō, respectively.

The founder developed many of the empty-handed techniques from traditional sword, spear and bayonet movements. Consequently, the practice of the weapons arts gives insight into the origin of techniques and movements, and reinforces the concepts of distance, timing, foot movement, presence and connectedness with one's training partner(s).[41]

Multiple attackers and randori

One feature of aikido is training to defend against multiple attackers, often called taninzudori, or taninzugake. Freestyle practice with multiple attackers called randori (乱取) is a key part of most curricula and is required for the higher level ranks.[42] Randori exercises a person's ability to intuitively perform techniques in an unstructured environment.[42] Strategic choice of techniques, based on how they reposition the student relative to other attackers, is important in randori training. For instance, an ura technique might be used to neutralise the current attacker while turning to face attackers approaching from behind.[4]

In Shodokan Aikido, randori differs in that it is not performed with multiple persons with defined roles of defender and attacker, but between two people, where both participants attack, defend, and counter at will. In this respect it resembles judo randori.[24][43]

Injuries

In applying a technique during training, it is the responsibility of tori to prevent injury to uke by employing a speed and force of application that is appropriate with their partner's proficiency in ukemi.[30] When injuries (especially to the joints) occur, they are often the result of a tori misjudging the ability of uke to receive the throw or pin.[44][45]

A study of injuries in the martial arts showed that the type of injuries varied considerably from one art to the other.[46] Soft tissue injuries are one of the most common types of injuries found within aikido,[46] as well as joint strain and stubbed fingers and toes.[45] Several deaths from head-and-neck injuries, caused by aggressive shihōnage in a senpai/kōhai hazing context, have been reported.[44]

Mental training

Aikido training is mental as well as physical, emphasizing the ability to relax the mind and body even under the stress of dangerous situations.[47] This is necessary to enable the practitioner to perform the 'enter-and-blend' movements that underlie aikido techniques, wherein an attack is met with confidence and directness.[48] Morihei Ueshiba once remarked that one "must be willing to receive 99% of an opponent's attack and stare death in the face" in order to execute techniques without hesitation.[49] As a martial art concerned not only with fighting proficiency but with the betterment of daily life, this mental aspect is of key importance to aikido practitioners.[50]

Uniforms and ranking

Aikido practitioners (commonly called aikidōka outside Japan) generally progress by promotion through a series of "grades" (kyū), followed by a series of "degrees" (dan), pursuant to formal testing procedures. Some aikido organizations use belts to distinguish practitioners' grades, often simply white and black belts to distinguish kyu and dan grades, though some use various belt colors. Testing requirements vary, so a particular rank in one organization is not comparable or interchangeable with the rank of another.[4] Some dōjōs have an age requirement before students can take the dan rank exam.

| rank | belt | color | type |

|---|---|---|---|

| kyū | white | mudansha / yūkyūsha | |

| dan | black | yūdansha |

The uniform worn for practicing aikido (aikidōgi) is similar to the training uniform (keikogi) used in most other modern martial arts; simple trousers and a wraparound jacket, usually white. Both thick ("judo-style"), and thin ("karate-style") cotton tops are used.[4] Aikido-specific tops are available with shorter sleeves which reach to just below the elbow.

Most aikido systems add a pair of wide pleated black or indigo trousers called a hakama (used also in Naginatajutsu, kendo, and iaido). In many schools, its use is reserved for practitioners with dan ranks or for instructors, while others allow all practitioners to wear a hakama regardless of rank.[4]

Criticisms

The most common criticism of aikido is that it suffers from a lack of realism in training. The attacks initiated by uke (and which tori must defend against) have been criticized as being "weak", "sloppy", and "little more than caricatures of an attack".[51][52] Weak attacks from uke allow for a conditioned response from tori, and result in underdevelopment of the skills needed for the safe and effective practice of both partners.[51] To counteract this, some styles allow students to become less compliant over time but, in keeping with the core philosophies, this is after having demonstrated proficiency in being able to protect themselves and their training partners. Shodokan Aikido addresses the issue by practising in a competitive format.[24] Such adaptations are debated between styles, with some maintaining that there is no need to adjust their methods because either the criticisms are unjustified, or that they are not training for self-defense or combat effectiveness, but spiritual, fitness or other reasons.[53]

Another criticism pertains to the shift in training focus after the end of Ueshiba's seclusion in Iwama from 1942 to the mid-1950s, as he increasingly emphasized the spiritual and philosophical aspects of aikido. As a result, strikes to vital points by tori, entering (irimi) and initiation of techniques by tori, the distinction between omote (front side) and ura (back side) techniques, and the use of weapons, were all de-emphasized or eliminated from practice. Some Aikido practitioners feel that lack of training in these areas leads to an overall loss of effectiveness.[54]

Conversely, some styles of aikido receive criticism for not placing enough importance on the spiritual practices emphasized by Ueshiba. According to Minoru Shibata of Aikido Journal, "O-Sensei's aikido was not a continuation and extension of the old and has a distinct discontinuity with past martial and philosophical concepts."[55] That is, that aikido practitioners who focus on aikido's roots in traditional jujutsu or kenjutsu are diverging from what Ueshiba taught. Such critics urge practitioners to embrace the assertion that "[Ueshiba's] transcendence to the spiritual and universal reality were the fundamentals [sic] of the paradigm that he demonstrated."[55]

References

- Sharif, Suliaman (2009). 50 Martial Arts Myths. New Media Entertainment. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-9677546-2-8.

- Ueshiba, Kisshōmaru (2004). The Art of Aikido: Principles and Essential Techniques. Kodansha International. p. 70. ISBN 4-7700-2945-4.

- Saotome, Mitsugi (1989). The Principles of Aikido. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-87773-409-3.

- Westbrook, Adele; Ratti, Oscar (1970). Aikido and the Dynamic Sphere. Tokyo, Japan: Charles E. Tuttle Company. pp. 16–96. ISBN 978-0-8048-0004-4.

- David Jones (2015). Martial Arts Training in Japan: A Guide for Westerners. Tuttle Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-4629-1828-7.

- Michael A. Gordon (2019). Aikido as Transformative and Embodied Pedagogy: Teacher as Healer. Springer. p. 28. ISBN 978-3-030-23953-4.

- Ueshiba, Morihei (2013). Budo: Teachings Of The Founder Of Aikido. New York: Kodansha America. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-1568364872.

- Tamura, Nobuyoshi (1991). Aikido – Etiquette et transmission. Manuel a l'usage des professeurs. Aix en Provence: Editions du Soleil Levant. ISBN 2-84028-000-0.

- Abe, Tadashi (1958). L'aiki-do – Methode unique creee par le maitre Morihei Ueshiba – L'arme et l'esprit du samourai japonais. France: Editions Chiron.

- Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Aikido". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006.

- Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Aikijujutsu". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014.

- Pranin, Stanley (2007). "Aiki". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- Pranin, Stanley (2007). "O-Sensei". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014.

- Draeger, Donn F. (1974). Modern Bujutsu & Budo – The Martial Arts and Ways of Japan. New York: Weatherhill. p. 137. ISBN 0-8348-0351-8.

- Stevens, John; Rinjiro, Shirata (1984). Aikido: The Way of Harmony. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala. pp. 3–17. ISBN 978-0-394-71426-4.

- Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Ueshiba, Morihei". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014.

- Homma, Gaku (1997). The Structure of Aikido: Volume 1: Kenjutsu and Taijutsu Sword and Open-Hand Movement Relationships (Structure of Aikido, Vol 1). Blue Snake Books. ISBN 1-883319-55-2.

- Pranin, Stanley. "Morihei Ueshiba and Onisaburo Deguchi". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007.

- Oomoto Foundation (2007). "The Teachings". Teachings and Scriptures. Netinformational Commission. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- Shishida, Fumiaki. "Aikido". Aikido Journal. Berkeley, CA: Shodokan Pub. ISBN 0-9647083-2-9. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007.

- Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Mochizuki, Minoru". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014.

- Robert W. Smith. "Journal of Non-lethal Combat: Judo in the US Air Force, 1953". ejmas.com.

- Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Yoshinkan Aikido". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007.

- Shishido, Fumiaki; Nariyama, Tetsuro (2002). Aikido: Tradition and the Competitive Edge. Shodokan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9647083-2-7.

- Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Tohei, Koichi". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 7 August 2007.

- Shioda, Gōzō; Johnston, Christopher (2000). Aikido Shugyo: Harmony in Confrontation. Translated by Payet, Jacques. Shindokan Books. ISBN 978-0-9687791-2-5.

- Reed, William (1997). "A Test Worth More than a Thousand Words". Archived from the original on 19 June 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- Homma, Gaku (1990). Aikido for Life. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-55643-078-7.

- Pranin, Stanley (2006). "Jumbi Taiso". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007.

- Homma, Gaku (1990). Aikido for Life. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. pp. 20–30. ISBN 978-1-55643-078-7.

- Shifflett, C.M. (1999). Aikido Exercises for Teaching and Training. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-55643-314-6.

- Pranin, Stanley (2008). "Ikkyo". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014.

- Pranin, Stanley (2008). "Yonkyo". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 22 January 2008.

- Pranin, Stanley (2008). "Kokyunage". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 22 January 2008.

- Pranin, Stanley (2008). "Juji Garami". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 22 January 2008.

- Pranin, Stanley (2008). "Kaitennage". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 22 January 2008.

- Amdur, Ellis. "Irimi". Aikido Journal. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007.

- Shioda, Gōzō (1968). Dynamic Aikido. Kodansha International. pp. 52–55. ISBN 978-0-87011-301-7.

- Scott, Nathan (2000). "Teachings of Ueshiba Morihei Sensei". Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 1 February 2007.

- Dang, Phong (2006). Aikido Weapons Techniques: The Wooden Sword, Stick, and Knife of Aikido. Charles E Tuttle Company. ISBN 978-0-8048-3641-8.

- Ratti, Oscar; Westbrook, Adele (1973). Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan. Edison, New Jersey: Castle Books. pp. 23, 356–359. ISBN 978-0-7858-1073-5.

- Ueshiba, Kisshomaru; Ueshiba, Moriteru (2002). Best Aikido: The Fundamentals (Illustrated Japanese Classics). Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2762-7.

- Aikido Randori: Tetsuro Nariyama. ASIN 0956620507. ISBN 978-0956620507 – via amazon.co.uk.CS1 maint: ASIN uses ISBN (link)

- Aikido and injuries: special report by Fumiaki Shishida Aiki News 1989;80 (April); partial English translation of article re-printed in Aikido Journal "Aikido and Injuries: Special Report". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- Pranin, Stanley (1983). "Aikido and Injuries". Encyclopedia of Aikido. Archived from the original on 22 January 2008.

- Zetaruk, M; Violán, MA; Zurakowski, D; Micheli, LJ (2005). "Injuries in martial arts: a comparison of five styles". British Journal of Sports Medicine. BMJ Publishing Group. 39 (1): 29–33. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2003.010322. PMC 1725005. PMID 15618336. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- Hyams, Joe (1979). Zen in the Martial Arts. New York: Bantam Books. pp. 53–57. ISBN 0-553-27559-3.

- Homma, Gaku (1990). Aikido for Life. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-1-55643-078-7.

- Ueshiba, Morihei (1992). The Art of Peace. Translation by Stevens, John. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0-87773-851-0.

- Heckler, Richard (1985). Aikido and the New Warrior. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. pp. 51–57. ISBN 978-0-938190-51-6.

- Pranin, Stanley (Fall 1990). "Aikido Practice Today". Aiki News. 86. Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 2 November 2007.

- Ledyard, George S. (June 2002). "Non-Traditional Attacks". aikiweb.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- Wagstaffe, Tony (30 March 2007). "In response to the articles by Stanley Pranin – Martial arts in a state of decline? An end to the collusion?". Aikido Journal. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- Pranin, Stanley (1994). "Challenging the Status Quo". Aiki News. 98. Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 2 November 2007.

- Shibata, Minoru J. (2007). "A Dilemma Deferred: An Identity Denied and Dismissed". Aikido Journal. Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

External links

- Aikido (martial art) at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- AikiWeb Aikido Information site on aikido, with essays, forums, gallery, reviews, columns, wiki and other information.