Hard and soft techniques

In martial arts, the terms hard and soft technique denote how forcefully a defender martial artist counters the force of an attack in armed and unarmed combat. In the East Asian martial arts, the corresponding hard technique and soft technique terms are 硬 (Japanese: gō, pinyin: yìng) and 柔 (Japanese: jū, pinyin: róu), hence Goju-ryu (hard-soft school), Shorinji Kempo principles of go-ho ("hard method") and ju-ho ("soft method"), Jujutsu ("art of softness") and Judo ("gentle way").

In European martial arts the same scale applies, especially in the German style of grappling and swordplay dating from the 14th century (e.g., the German school of fencing); the use of the terms hard and soft are otherwise translated as "strong" and "weak." In later European martial arts the scale becomes less of a philosophic concept and more of a scientific approach to where two swords connect upon one another and the options applicable to each in the circumstance, parting further from the original meaning as time went along.

Regardless of origins and styles, "hard and soft" can be seen as simply firm/unyielding in opposition or complementary to pliant/yielding; each has its application and must be used in its own way, and each makes use of specific principles of timing and biomechanics.

In addition to describing a physical technique applied with minimal force, "soft" also sometimes refers to elements of a discipline which are viewed as less purely physical; for example, martial arts that are said to be "internal styles" are sometimes also known as "soft styles", for their focus on mental techniques or spiritual pursuits.

Hard technique

A hard technique meets force with force, either with a linear, head-on force-blocking technique, or by diagonally cutting the strike with one's force. Although hard techniques require greater strength for successful execution, it is the mechanics of the technique that accomplish the defense. Examples are:

- A kickboxing low kick aimed to break the attacker's leg.

- A Karate block aimed to break or halt the attacker's arm.

Hard techniques can be used in offense, defense, and counter-offense. They are affected by footwork and skeletal alignment. For the most part, hard techniques are direct. The key point of a hard technique is interrupting the flow of attack: in counter-offense they look to break the attack and in offense they are direct and committed blows or throws. Hard technique use muscle more than soft techniques.

Soft technique

The goal of the soft technique is deflecting the attacker’s force to his or her disadvantage, with the defender exerting minimal force and requiring minimal strength.[1] With a soft technique, the defender uses the attacker's force and momentum against him or her, by leading the attack(er) in a direction to where the defender will be advantageously positioned (tai sabaki) and the attacker off balance; a seamless movement then effects the appropriate soft technique. In some styles of martial art like Wing Chun, a series of progressively difficult, two-student training drills, such as pushing hands or sticky hands, teach to exercise the soft-technique(s); hence:

(1) The defender leads the attack by redirecting the attacker's forces against him or her, or away from the defender — instead of meeting the attack with a block. The mechanics of soft technique defenses usually are circular: Yielding is meeting the force with no resistance, like a projectile glancing off a surface without damaging it. Another example could be: an Aikido check/block to an attacker's arm, which re-directs the incoming energy of the blow.

(2) The soft technique usually is applied when the attacker is off-balance, thus the defender achieves the "maximum efficiency" ideal posited by Kano Jigoro (1860–1938), the founder of judo. The Taijiquan (T'ai chi ch'uan) histories report "a force of four taels being able to move a thousand catties", referring to the principle of Taiji — a moving mass can seem weightless. Soft techniques — throws, armlocks, etc. — might resemble hard martial art techniques, yet are distinct because their application requires minimal force. (see kuzushi)

- In Fencing, with a parry, the defender guides or checks the attacker's sword away from himself, rather than endure the force of a direct block; it likely is followed by riposte and counter-riposte.

- In Classical Fencing, other techniques appear in all forms of swordplay which fall into the soft category, the most obvious being the disengage where the fencer or swordsman uses the pressure of his opponent to disengage and change lines on his opponent giving him an advantage in the bind.

- In Bare-knuckle boxing or Pugilism, with a parry, the defender guides or checks the attacker’s blow away from himself, attempting to cause the attacker to over commit to his blow and allow an easy riposte and counter-riposte.

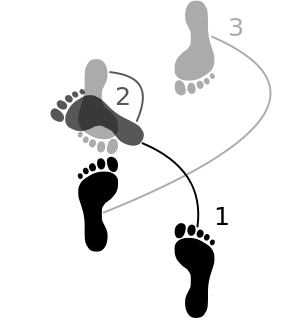

- In Judo and Jujutsu when the attacker (uke) pushes towards the defender (tori), the tori drops under the uke, whilst lifting the uke over himself, effecting the Tomoe Nage throw with one of his legs. The technique is categorized as a "front sacrifice technique" in judo and jujutsu styles. The push from the uke can be direct, or it can be a response to a push from the tori.

- With martial arts styles such as T'ien Ti Tao Ch'uan-shu P'ai the soft style is also in keeping with the Taoist philosophy, the idea that the technique can also be applied in mental terms as well as physical.

Soft techniques can be used in offense but are more likely to appear in defense and counter offense. Much like hard techniques they are effected by foot work and skeletal alignment. Where a hard technique in defense often aims to interrupt the flow of attack; a soft technique aims to misdirect it, move around it or draw it into over commitment, in counter offense a soft technique may appear as a slip or a vault or simply using the momentum of a technique against the user. Soft techniques in offense would usually only include feints and pulling motions but the definition and categorization may change from one art form to another.

Soft techniques are also characterized as being circular in nature and considered internal (using Qi (Chinese) or ki (Japanese and Korean)) by martial arts such as t'ai chi ch'uan, hapkido and aikido.

Principle of Jū

The principle of Ju (柔, Jū, Yawara) underlies all classical Bujutsu methods and was adopted by the developers of the Budō disciplines. Acting according to the principle of Jū, the classical warrior could intercept and momentarily control his enemy's blade when attacked, then, in a flash, could counter-attack with a force powerful enough to cleave armor and kill the foe. The same principle of Jū permitted an unarmed exponent to unbalance and hurl his foe to the ground. Terms like "Jūjutsu" and "Yawara" made the principle of Jū the all-pervading one in methods cataloged under these terms. That principle was rooted in the concept of pliancy or flexibility, as understood in both a mental and a physical context. To apply the principle of Jū, the exponent had to be both mentally and physically capable of adapting himself to whatever situation his adversary might impose on him.

There are two aspects of the principle of Jū that are in constant operation, both interchangeable and inseparable. One aspect is that of "yielding", and is manifest in the exponent's actions that accept the enemy's force of attack, rather than oppose him by meeting his force directly with an equal or greater force, when it is advantageous to do so. It is economical in terms of energy to accept the foe's force by intercepting and warding it off without directly opposing it; but the tactic by which the force of the foe is dissipated may be as forcefully made as was the foe's original action.

The principle of Jū is incomplete at this point because yielding is essentially only a neutralization of the enemy's force. While giving way to the enemy's force of attack there must instantly be applied an action that takes advantage of the enemy, now occupied with his attack, in the form of a counterattack. This second aspect of the principle of Jū makes allowance for situations in which yielding is impossible because it would lead to disaster. In such cases "resistance" is justified. But such opposition to the enemy's actions is only momentary and is quickly followed by an action based on the first aspect of Jū, that of yielding.

Distinction from "external and internal"

There is disagreement among different schools of Chinese martial arts about how the two concepts of "Hard/Soft" and "External/Internal" apply to their styles.

Among styles that this terminology is applied to, traditional Taijiquan equates the terms while maintaining several finer shades of distinction.[2]

Hard styles typically use a penetrating, linear "external force" whereas soft styles usually use a circular, flowing "internal force" where the energy of the technique goes completely through the opponent for hard/external strikes while the energy of the technique is mostly absorbed by the opponent for soft/internal strikes.[3]

See also

References

- Fu, Zhongwen (2006) [1996]. Mastering Yang Style Taijiquan. Louis Swaine. Berkeley, California: Blue Snake Books. ISBN 1-58394-152-5.

- c.f. The martial arts FAQ, built up over years of discussion on rec.martial.arts. In part one, there is an entry for hard vs soft and internal vs external.

- TanDaoKungFu, TanDao Fight Lab #2 Hard & Soft Palm Strikes, Tandao.com, retrieved 2019-01-19 Youtube, July 16, 2010 Lawrence Tan

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Tai chi chuan |