Professional boxing

Professional boxing, or prizefighting, is regulated, sanctioned boxing. Professional boxing bouts are fought for a purse that is divided between the boxers as determined by contract. Most professional bouts are supervised by a regulatory authority to guarantee the fighters' safety. Most high-profile bouts obtain the endorsement of a sanctioning body, which awards championship belts, establishes rules, and assigns its own judges and referee.

In contrast with amateur boxing, professional bouts are typically much longer and can last up to twelve rounds, though less significant fights can be as short as four rounds. Protective headgear is not permitted, and boxers are generally allowed to take substantial punishment before a fight is halted. Professional boxing has enjoyed a much higher profile than amateur boxing throughout the 20th century and beyond.

In Cuba professional boxing is banned (as of 2020).[1] So was also the case in Sweden between 1970 and 2007, and Norway between 1981 and 2014.[2]

Early history

In 1891, the National Sporting Club (N.S.C.), a private club in London, began to promote professional glove fights at its own premises, and created nine of its own rules to augment the Queensberry Rules. These rules specified more accurately the role of the officials, and produced a system of scoring that enabled the referee to decide the result of a fight. The British Boxing Board of Control (BBBofC) was first formed in 1919 with close links to the N.S.C., and was re-formed in 1929 after the N.S.C. closed.[4]

In 1909, the first of twenty-two belts were presented by the fifth Earl of Lonsdale to the winner of a British title fight held at the N.S.C. In 1929, the BBBofC continued to award Lonsdale Belts to any British boxer who won three title fights in the same weight division. The "title fight" has always been the focal point in professional boxing. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, however, there were title fights at each weight. Promoters who could stage profitable title fights became influential in the sport, as did boxers' managers. The best promoters and managers have been instrumental in bringing boxing to new audiences and provoking media and public interest. The most famous of all three-way partnership (fighter-manager-promoter) was that of Jack Dempsey (heavyweight champion 1919–1926), his manager Jack Kearns, and the promoter Tex Rickard. Together they grossed US$8.4 million in only five fights between 1921 and 1927 and ushered in a "golden age" of popularity for professional boxing in the 1920s.[5] They were also responsible for the first live radio broadcast of a title fight (Dempsey v. Georges Carpentier, in 1921). In the United Kingdom, Jack Solomons' success as a fight promoter helped re-establish professional boxing after the Second World War and made the UK a popular place for title fights in the 1950s and 1960s.

Modern history

1900 to 1920

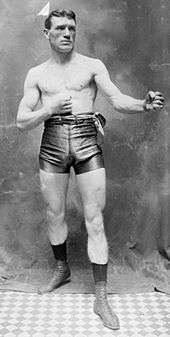

In the early twentieth century, most professional bouts took place in the United States and Britain, and champions were recognised by popular consensus as expressed in the newspapers of the day. Among the great champions of the era were the peerless heavyweight Jim Jeffries and Bob Fitzsimmons, who weighed less than 12 stone (164 pounds), but won world titles at middleweight (1892), light heavyweight (1903), and heavyweight (1897). Other famous champions included light heavyweight Philadelphia Jack O'Brien and middleweight Tommy Ryan. On May 12, 1902 lightweight Joe Gans became the first black American to be boxing champion. Despite the public's enthusiasm, this was an era of far-reaching regulation of the sport, often with the stated goal of outright prohibition. In 1900, the State of New York enacted the Lewis Law, banned prizefights except for those held in private athletic clubs between members. Thus, when introducing the fighters, the announcer frequently added the phrase "Both members of this club", as George Wesley Bellows titled one of his paintings.[6] The western region of the United States tended to be more tolerant of prizefights in this era, although the private club arrangement was standard practice here as well, San Francisco's California Athletic Club being a prominent example.[6]

On December 26, 1908, heavyweight Jack Johnson became the first black heavyweight champion and a highly controversial figure in that racially charged era. Prizefights often had unlimited rounds, and could easily become endurance tests, favouring patient tacticians like Johnson. At lighter weights, ten round fights were common, and lightweight Benny Leonard dominated his division from the late teens into the early twenties.

Prizefighting champions in this period were the premier sports celebrities, and a championship event generated intense public interest. Long before bars became popular venues in which to watch sporting events on television, enterprising saloon keepers were known to set up ticker machines and announce the progress of an important bout, blow by blow. Local kids often hung about outside the saloon doors, hoping for news of the fight. Harpo Marx, then fifteen, recounted vicariously experiencing the 1904 Jeffries-Munroe championship fight in this way.[7]

1920 to 1940

In the 1920s, prizefighting was the pre-eminent sport in the United States, and no figure loomed larger than Jack Dempsey, who became world heavyweight champion after brutally defeating Jess Willard. Dempsey was one of the hardest punchers of all time and as Bert Randolph Sugar put it, "had a left hook from hell". He is remembered for his iconic fight with Luis Ángel Firpo, which was followed by a lavish life of celebrity away from the ring. The enormously popular Dempsey would conclude his career with a memorable two bouts with Gene Tunney, breaking the $1 million gate threshold for the first time. Although Tunney dominated both fights, Dempsey retained the public's sympathy, especially after the controversy of a "long count" in their second fight. This fight introduced the new rule that the counting of a downed opponent would not begin until the standing opponent went into a neutral corner. At this time, rules were negotiated by parties, as there were no sanctioning bodies.

The New York State Athletic Commission took a more prominent role in organizing fights in the 1930s. Famous champions of that era included the German heavyweight Max Schmeling and the American Max Baer, who wielded a devastating right hand. Baer was defeated by "Cinderella Man" James Braddock, a former light heavyweight contender before a series of injuries and setbacks during the Great Depression and was at one point even stripped of his license. Most famous of all was Joe Louis, who avenged an earlier defeat by demolishing Schmeling in the first round of their 1938 rematch. Louis was voted the best puncher of all time by The Ring, and is arguably the greatest heavyweight of all time. In 1938, Henry Armstrong became the only boxer to hold titles in three different weight classes at the same time (featherweight, lightweight, and welterweight). His attempt at winning the middleweight title would be thwarted in 1940.

1940 to 1960

The Second World War brought a lull in competitive boxing, and champion Louis fought mostly exhibitions. After the war, Louis continued his reign, but new stars emerged in other divisions, such as the inimitable featherweight Willie Pep, who won over 200 fights, and most notably Sugar Ray Robinson, widely regarded as the greatest pound-for-pound fighter of all time. Robinson held the world welterweight title from 1946 to 1951 and the world middleweight title a record five times from 1951 to 1960. His notable rivals included Jake LaMotta, Gene Fullmer, and Carmen Basilio. Unfortunately, many fights in the 1940s and 1950s were marred by suspected mafia involvement, though some fighters like Robinson and Basilio openly resisted mob influence.

Among the heavyweights, Joe Louis retained his title until his 1949 retirement, having held the championship for an unprecedented eleven years. Ezzard Charles and Jersey Joe Walcott succeeded him as champion, but they were soon outshone by the remarkable Rocky Marciano, who compiled an astounding 49–0 record before retiring as world champion. Among his opponents was the ageless Archie Moore, who held the world light heavyweight title for ten years and scored more knockout victories than any other boxer in history.

1960 to 1980

In the early 1960s, the seemingly invincible Sonny Liston captured the public imagination with his one-sided destruction of two-time heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson. One of the last mob-connected fighters, Liston had his mystique shattered in two controversial losses to the brash upstart Cassius Clay, who changed his name to Muhammad Ali after becoming champion. Ali would become the most iconic figure in boxing history, transcending the sport and achieving global recognition. His refusal to serve in the Vietnam War resulted in the stripping of his title, and tore down the barrier between sport and culture.

After three years of inactivity, Ali returned to the sport, leading to his first epic clash with Joe Frazier in 1971, ushering in a "golden age" of heavyweight boxing. Ali, Frazier, and the heavy-hitting George Foreman were the top fighters in a division overloaded with talent. Among the middleweights, Argentine Carlos Monzón emerged as a dominant champion, reigning from 1970 to his retirement in 1977, after an unprecedented 14 title defenses. Roberto Durán dismantled opponents for 6½ years as lightweight champion, Defending the title 12 times, 11 by knockout.

The late 1970s witnessed the end of universally recognised champions, as the WBC and WBA began to recognise different champions and top contenders, ushering in the era of multiple champions, unworthy mandatory challengers, and general corruption that came to be associated with sanctioning bodies in later decades.

The end of this decade also saw the sport begin to become more oriented toward the casino industry. The Caesars Palace hotel in Las Vegas began to host major bouts featuring George Foreman, Ron Lyle, Muhammad Ali, Roberto Durán, Sugar Ray Leonard, Marvin Hagler and Thomas Hearns. Also, public broadcasts would be replaced by closed-circuit, and ultimately pay-per-view, broadcasts, as the boxing audience shrank in numbers.

1980 to 2000

In the early 1980s Larry Holmes was a lone heavyweight talent in a division full of pretenders, so the most compelling boxing matchups were to be found in the lower weight classes. Roberto Durán dominated the lightweight division and became welterweight champion, but quit during the 8th round in his second fight with Sugar Ray Leonard (the famous "no mas" fight of Nov. 1980), who emerged as the best fighter of the decade. Leonard went on to knock out the formidable Thomas Hearns in 1981. Meanwhile, the junior welterweight division was ruled by Aaron Pryor, who made 10 title defenses from 1980 to 1985, before vacating the championship.

The prestigious middleweight division was dominated by "Marvelous" Marvin Hagler, who fought Thomas Hearns at Caesars Palace on April 15, 1985. The fight was billed as "The War", and it lived up to its billing. As soon as the bell rang, both fighters ran towards the centre of the ring and began trading hooks and uppercuts nonstop. This continued into round three, when Hagler overwhelmed Hearns and knocked him out in brutal fashion. This fight made Hagler famous; he was able to lure Ray Leonard out of retirement in 1987, but lost in a highly-controversial decision. Hagler retired from boxing immediately after that fight.

In the latter half of the decade young heavyweight Mike Tyson emerged as a serious contender. Nicknamed "Iron Mike", Tyson won the heavyweight unification series to become world heavyweight champion at the age of 20 and the first undisputed champion in a decade. Tyson soon became the most widely known boxer since Ali due to an aura of unrestrained ferocity, such as that exuded by Jack Dempsey or Sonny Liston.

Much like Liston, Tyson's career was marked by controversy and self-destruction. He was accused of domestic violence against his wife Robin Givens, whom he soon divorced. Meanwhile, he lost his title to 42-1 underdog James Douglas. His progress toward another title shot was derailed by allegations of rape made by Desiree Washington, a beauty pageant queen. In 1992 Tyson was imprisoned for rape, and released three years later. With Tyson removed from the heavyweight picture, Evander Holyfield and Riddick Bowe emerged as top heavyweights in the early nineties, facing each other in three bouts.

Meanwhile, at light welterweight, Mexican Julio César Chávez compiled an official record of 89-0 before fighting to a controversial draw in 1993 with Pernell Whitaker, who later also became a great boxer. In the late 1990s Chavez was superseded by Olympic gold medalist Oscar De La Hoya, who became the most popular pay-per-view draw of his era. De la Hoya won championships in six weight classes, competing with fighters including Chavez, Whitaker, and Félix Trinidad.

In the late 1990s Mike Tyson made a comeback, which took an unexpected turn when he was defeated by heavy underdog Evander Holyfield in 1996. In their 1997 rematch, Tyson bit a chunk from Holyfield's ear, resulting in his disqualification; Tyson's boxing license was revoked by the Nevada State Athletic Commission for one year and he was fined US$3 million. Holyfield won two of the three title belts, but lost a final match in 1999 with WBC champion Lennox Lewis, who became undisputed champion.

2000 to present

The last decade has witnessed a continued decline in the popularity of boxing in the United States, marked by a malaise in the heavyweight division and the increased competition in the Pay-Per-View market from MMA and its main promotion, the UFC.[8][9] The sport has grown in Germany and Eastern Europe, and is also currently strong in Britain. This cultural shift is reflected in some of the changes in championship title holders, especially in the upper weight divisions.

The light heavyweight division was dominated in the early part of the decade by Roy Jones, Jr., a former middleweight champion, and the Polish-German Dariusz Michalczewski. Michalczewski held the WBO title, while Jones held the WBC, WBA, and IBF titles, two of which had been relinquished by Michalczewski. The two fighters never met, due to a dispute over whether the fight would be held in the U.S. or in Germany. This sort of dispute would be repeated among other top fighters, as Germany emerged as a top venue for world class boxing.

The Ukrainian Klitschko brothers, Wladimir and Vitali, both of whom held versions of the heavyweight title. The Klitschkos were often depicted as representing a new generation of fighters from ex-Soviet republics, possessing great size, yet considerable skill and stamina, developed by years of amateur experience. Most versions of the heavyweight title were held by fighters from the former Soviet Union.

Since the retirement of Lennox Lewis in 2004, the heavyweight division has been criticised as lacking talent or depth, especially among American fighters. This has resulted in a higher profile for fighters in lower weight classes, including the age-defying middleweight and light heavyweight champion Bernard Hopkins, and the undefeated multiple weight division champion Floyd Mayweather, Jr., who won a 2007 split decision over Oscar De La Hoya in a record-breaking pay-per-view event. Billed as the "fight to save boxing", the success of this event shows that American boxing still retains a considerable core audience when its product is of descent from the American continent.

Other notable fighters in even lower weight classes are experiencing unprecedented popularity today. In the last five years junior lightweights Marco Antonio Barrera, Erik Morales, Juan Manuel Márquez and multiple weight division champion Manny Pacquiao have fought numerous times on pay-per-view. These small fighters often display tremendous punching power for their size, producing exciting fights such as the incredible 2005 bout between Castillo and the late Diego Corrales.

Interest in the lower weight divisions further increased with the possibility of a superfight between two of the current best fighters in the world, Manny Pacquiao and Floyd Mayweather, Jr. Experts predicted this would break current pay-per-view records, due to the tremendous public demand for the fight. Long negotiations finally culminated in the Mayweather-Pacquiao fight on May 2, 2015, six years after negotiation first began and resulted in estimated revenues of $450,000,000.[10]

Length of bouts

Professional bouts are limited to a maximum of twelve rounds, most are fought over four, six, eight or ten rounds depending upon the experience of the boxers. Through the early twentieth century, it was common for fights to have unlimited rounds, ending only when one fighter quit or the fight was stopped by police. In the 1910s and 1920s, a fifteen-round limit gradually became the norm, benefiting high-energy fighters like Jack Dempsey.

For decades, from the 1920s to the 1980s, world championship matches in professional boxing were scheduled for fifteen rounds, but that changed after a November 13, 1982 WBA Lightweight title bout ended with the death of boxer Duk Koo Kim in a fight against Ray Mancini in the 14th round of a nationally televised championship fight on CBS. Exactly three months after the fatal fight, the WBC reduced the number of their championship fights to 12 rounds. The WBA even stripped a fighter of his championship in 1983 because the fight had been a 15-round bout, shortly after the rule was changed to 12 rounds. By 1988, to the displeasure of some boxing purists, all fights had been reduced to a maximum of 12 rounds only, partially for safety, and partially for television, as a 12-round bout could be broadcast in a one-hour television block (pre-match, then the bout which lasts 48 minutes overall, decision, and interviews). In contrast, a 15-round bout could require up to 90 minutes to broadcast (bout lasts 60 minutes, and both pre and post bout coverage including decision).

Scoring

If a knockout or disqualification does not occur, the fight is determined by a points decision. In the early days of boxing, the referee decided the winner by raising his arm at the end of the bout, a practice that is still used for some professional bouts in the United Kingdom. In the early twentieth century, it became common for the referee or judge to score bouts by the number of rounds won. To improve the reliability of scoring, two ringside judges were added besides the referee, and the winner was decided by majority decision. Since the late twentieth century, it has become common practice for all three judges to be ringside observers, though the referee still has the authority to stop a fight or deduct points.

At the end of the fight, the judges scores are tallied. If all three judges choose the same fighter as the winner, that fighter wins by unanimous decision. If two judges have one boxer winning the fight and the third judge scores it a draw, the boxer wins by majority decision. If two judges have one boxer winning the fight and the third judge has the other boxer winning, the first boxer wins by split decision. If one judge chooses one boxer as the winner, the second judge chooses the other boxer, and the third judge calls it a draw, then the bout is ruled a Split draw. The bout is also ruled a Majority Draw if at least two out of three judges score the fight a draw, regardless of the third score.

10-Point system

The 10 Point system was first introduced in 1968 by the World Boxing Council (WBC) as a rational way of scoring fights.[11] It was viewed as such because it allowed judges to reward knockdowns and distinguish between close rounds, as well as rounds where one fighter clearly dominated their opponent. Furthermore, the subsequent adoption of this system, both nationally and internationally, allowed for greater judging consistency, which was something that was sorely needed at the time.[11] There are many factors that inform the judge's decision but the most important of these are: clean punching, effective aggressiveness, ring generalship and defense. Judges use these metrics as a means of discerning which fighter has a clear advantage over the other, regardless of how minute the advantage.

The Evolution of the 10-Point System

Modern boxing rules were initially derived from the Marquess of Queensbury rules which mainly outlined core aspects of the sport, such as the establishment of rounds and their duration, as well as the determination of proper attire in the ring such as gloves and wraps.[12] These rules did not, however, provide unified guidelines for scoring fights and instead left this in the hands of individual sanctioning organizations. This meant that fights would be scored differently depending on the rules established by the governing body overseeing the fight. It is from this environment that the 10-Point System was born.[11] The adoption of this system, both nationally and internationally, established the foundation for greater judging consistency in professional boxing.[11][13]

How the System Works

In the event the winner of a bout cannot be determined by a knockout, technical knockout, or disqualification, the final decision rests in the hands of three ringside judges approved by the commission. The three judges are usually seated along the edge of the boxing ring, separated from each other. The judges are forbidden from sharing their scores with each other or consulting with one another.[12] At the end of each round, judges must hand in their scores to the referee who then hands them to the clerk who records and totals the final scores.[12] Judges are to award 10 points (less any point deductions) to the victor of the round and a lesser score (less any point deductions) to the loser. The losing contestant's score can vary depending on different factors.

The 10-point Must System is the most widely used scoring system since the mid-twentieth century. It is so named because a judge "must" award ten points to at least one fighter each round (before deductions for fouls). Most rounds are scored 10–9, with 10 points for the fighter who won the round, and 9 points for the fighter the judge believes lost the round. If a round is judged to be even, it is scored 10-10. For each knockdown in a round, the judge deducts an additional point from the fighter knocked down, resulting in a 10–8 score if there is one knockdown or a 10–7 score if there are two knockdowns. If the referee instructs the judges to deduct a point for a foul, this deduction is applied after the preliminary computation. So, if a fighter wins a round, but is penalised for a foul, the score changes from 10–9 to 9-9. If that same fighter scored a knockdown in the round, the score would change from 10–8 in his favour to 9–8. While uncommon, if a fighter completely dominates a round but does not score a knockdown, a judge can still score that round 10–8.

Other scoring systems have also been used in various locations, including the five-point must system (in which the winning fighter is awarded five points, the loser four or fewer), the one-point system (in which the winning fighter is awarded one or more points, and the losing fighter is awarded zero), and the rounds system which simply awards the round to the winning fighter. In the rounds system, the bout is won by the fighter determined to have won more rounds. This system often used a supplemental points system (generally the ten-point must) in the case of even rounds.

If a fight is stopped due to an injury that the referee has ruled to be the result of an unintentional foul, the fight goes to the scorecards only if a specified number of rounds (usually three, sometimes four) have been completed. Whoever is ahead on the scorecards wins by a technical decision. If the required number of rounds has not been completed, the fight is declared a technical draw or a no contest.

If a fight is stopped due to a cut resulting from a legal punch, the other participant is awarded a technical knockout win. For this reason, fighters often employ cutmen, whose job is to treat cuts between rounds so that the boxer is able to continue despite the cut.[14]

Judges do not have the ability to disregard an official knockdown. If the referee declares a fighter going down to be a knockdown, the judges must score it as such.

Championships

In the first part of the 20th century, the United States became the centre for professional boxing. It was generally accepted that the "world champions" were those listed by the Police Gazette.[15] After 1920, the National Boxing Association (NBA) began to sanction "title fights." Also during that time, The Ring was founded, and it listed champions and awarded championship belts. The NBA was renamed in 1962 and became the World Boxing Association (WBA). The following year, a rival body, the World Boxing Council (WBC) was formed.[16] In 1983, the International Boxing Federation (IBF) was formed. In 1988, another world sanctioning body, the World Boxing Organization (WBO) was formed. In the 2010s a boxer had to be recognized by these four bodies to be the undisputed world champion; minor bodies like the International Boxing Organization (IBO) and World Boxing Union (WBU) are disregarded. Regional sanctioning bodies such as the North American Boxing Federation (NABF), the North American Boxing Council (NABC) and the United States Boxing Association (USBA) also awarded championships. The Ring magazine also continued listing the world champion of each weight division, and its rankings continue to be appreciated by fans.

Major sanctioning bodies

- International Boxing Federation (IBF)

- World Boxing Association (WBA)

- World Boxing Council (WBC)

- World Boxing Organization (WBO)

See also

Citations

- Combat sports: Professional boxing championship rules; Government of Ontario. (2016, June 28). Retrieved November 11, 2018

- Did Lennox Lewis Beat Evander Holyfield?: Methods for Analysing Small Sample Interrater Agreement Problems; Herbert K. H. Lee, Cork, D., & Algranati, D. (2002). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series D (The Statistician), 51(2), pp. 129–146.

- Rules for IBF, USBA & Intercontinental Championship and Elimination Bouts; IBF, O. (2015, June). Retrieved November 7, 2018

- WORLD BOXING FEDERATION RULES & REGULATIONS OF CHAMPIONSHIP CONTESTS; WBF. (2009). Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ABC Unified Rules of Boxing; WBO, E., & ABC. (2008, July 3). Retrieved November 6, 2018.

References

- Fish, Jim (June 26, 2007). "Boxers bounce back in Sweden". BBC News.

- Hjellen, Bjørnar (December 16, 2014). "Brækhus fikk drømmen oppfylt". BBC News.

- Leonard–Cushing fight Part of the Library of Congress/Inventing Entertainment educational website. Retrieved 12/14/06.

- "boxing-gyms.com". boxing-gyms.com. Archived from the original on 2017-04-04. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

- "Jack Dempsey - Boxer". boxrec.com.

- Robert G. Rodriguez. The regulation of boxing, p32. McFarland & Co., Jefferson, NC 2008

- Harpo Speaks! pp 59-60. Limelight Editions, New York, 1961

- "Jackson: Boxing's black eye - ESPN Page 2". go.com.

- Hayward, Paul (2011-11-12). "No fighting against the painful decline in heavyweight boxing". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

- "Pacquino Mayweather fight". sbsun.com.

- Tom, Kaczmarek (1996). You be the boxing judge! : judging professional boxing for the TV boxing fan. Pittsburgh, Pa.: Dorrance Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0805939033. OCLC 39257557.

- Lee, Herbert K.H; Cork, Daniel.L; Algranati, David.J (2002). "Did Lennox Lewis Beat Evander Holyfield?: Methods for Analysing Small Sample Interrater Agreement Problems". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. series D ( the statistician) (51(2)): 129–146. JSTOR 3650314.

- [https/:www.lawinsport.com/topics/articles/item/ever-wondered-how-professional-boxing-s-scoring-system-works How it works];

- Bert Randolph Sugar (2001). "Boxing" Archived 2006-06-19 at the Wayback Machine, World Book Online Americas Edition

- "The Police Gazette". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Piero Pini and Professor Ramón G. Velásquez (2006). History & Founding Fathers WBCboxing "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2003-12-16. Retrieved 2006-06-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)