Kyūjutsu

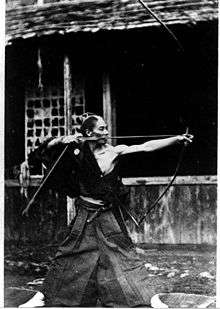

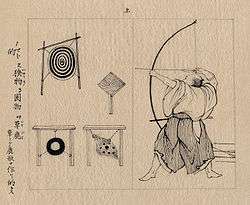

Kyūjutsu (弓術) ("art of archery") is the traditional Japanese martial art of wielding a bow (yumi) as practiced by the samurai class of feudal Japan.[1] Although the samurai are perhaps best known for their swordsmanship with a katana (kenjutsu), kyūjutsu was actually considered a more vital skill for a significant portion of Japanese history. During the majority of the Kamakura period through the Muromachi period (c.1185–c.1568), the bow was almost exclusively the symbol of the professional warrior, and way of life of the warrior was referred to as "the way of the horse and bow" (弓馬の道, kyūba no michi).[2]

| |

| Focus | Weaponry - Bow |

|---|---|

| Hardness | Competitive |

| Country of origin | |

| Creator | No single creator |

| Parenthood | Historical |

| Olympic sport | No |

History

The beginning of archery in Japan is, as elsewhere, pre-historical. The first images picturing the distinct Japanese asymmetrical longbow are from the Yayoi period (ca. 500 BC–300 AD). The first written document describing Japanese archery is the Chinese chronicle Weishu (dated around 297 AD), which tells how in the Japanese isles people use "a wooden bow that is short from the bottom and long from the top."[3]

Emergence

The changing of society and the military class (samurai) taking power at the end of the first millennium created a requirement for education in archery. This led to the birth of the first kyujutsu ryūha (style), the Henmi-ryū, founded by Henmi Kiyomitsu in the 12th century.[4] The Takeda-ryū and the mounted archery school Ogasawara-ryū were later founded by his descendants. The need for archers grew dramatically during the Genpei War (1180–1185) and as a result the founder of the Ogasawara-ryū (Ogasawara Nagakiyo), began teaching yabusame (mounted archery).

Civil war

From the 15th to the 16th century, Japan was ravaged by civil war. In the latter part of the 15th century Heki Danjō Masatsugu revolutionized archery with his new and accurate approach called hi, kan, chū (fly, pierce, center), and his footman's archery spread rapidly. Many new schools were formed, some of which, such as Heki-ryū Chikurin-ha, Heki-ryū Sekka-ha and Heki-ryū Insai-ha, remain today.

16th century

The yumi (Japanese bow) as a weapon of war began its decline after the Portuguese arrived in Japan in 1543 bringing firearms with them in the form of the matchlock.[5] The Japanese soon started to manufacture their own version of the matchlock called tanegashima and eventually the tanegashima and the yari (spear) became the weapons of choice. The yumi, however, would be continued to be used alongside the tanegashima for a period of time because of its longer reach, accuracy, and especially because it had a rate of fire 30–40 times faster. The tanegashima however did not require the same amount of training as a yumi, allowing Oda Nobunaga's army consisting mainly of farmers armed with tanegashima to annihilate a traditional samurai cavalry in a single battle in 1575.

17th century on

During the Tokugawa period (1603–1868) Japan was turned inward as a hierarchical caste society in which the samurai were at the top. There was an extended era of peace during which the samurai moved to administrative duty, although the traditional fighting skills were still esteemed. During this period archery became a "voluntary" skill, practiced partly in the court in ceremonial form, partly as different kinds of competition. Archery spread also outside the warrior class. The samurai were affected by the straightforward philosophy and aim for self-control in Zen Buddhism that was introduced by Chinese monks. Earlier archery had been called kyūjutsu, the skill of bow, but monks acting even as martial arts teachers led to creation of a new concept: kyūdō. Since then, especially due to changes brought by Japan opening up to the outside world at the beginning of the Meiji era (1868–1912), kyujutsu has experienced a steep decline.

Old school

- Ogasawara ryu 小笠原流

- Heki ryu 日置流

- Heki ryu Sekka-ha 日置流 雪荷派

- Heki ryu Dosetsu-ha 日置流 道雪派

- Heki ryu Chikurin-ha 日置流 竹林派

- Heki ryu Izumo-ha 日置流 出雲派

- Heki ryu Insai-ha 日置流 印西派

- Heki ryu Yoshida-ha 日置流 吉田派

- Yamato ryu 大和流

- Yoshida ryu 吉田流

- Ikkan ryu 一貫流

References

- Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior, Author Clive Sinclaire, Publisher Globe Pequot, 2004, ISBN 1-59228-720-4, ISBN 978-1-59228-720-8 P.121

- Mol, Serge (2001). Classical Fighting Arts of Japan: A Complete Guide to Koryū Jūjutsu. Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International Ltd. pp. 70. ISBN 4-7700-2619-6.

- Yamada Shōji, The Myth of Zen in the Art of Archery, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 2001 28/1–2

- Thomas A. Green, Martial Arts of the World, 2001

- Tanegashima: the arrival of Europe in Japan, Olof G. Lidin, Nordic Institute of Asian Studies, NIAS Press, 2002 P.1-14