Jemdet Nasr period

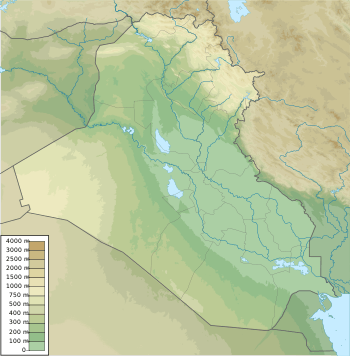

The Jemdet Nasr Period is an archaeological culture in southern Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). It is generally dated from 3100–2900 BC. It is named after the type site Tell Jemdet Nasr, where the assemblage typical for this period was first recognized. Its geographical distribution is limited to south-central Iraq. The culture of the proto-historical Jemdet Nasr period is a local development out of the preceding Uruk period and continues into the Early Dynastic I period.

Area corresponding to the Jemdet Nasr culture in light brown. The area corresponding to the Uruk culture is in yellow. | |

| Geographical range | Mesopotamia |

|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age |

| Dates | circa 3100 BC – circa 2900 BC |

| Type site | Tell Jemdet Nasr |

| Major sites | Tell Abu Salabikh, Tell Fara, Tell Khafajah, Nippur, Tell Uqair, Tell el-Muqayyar, and Eanna district, Bit Resh (Kullaba), and Irigal |

| Preceded by | Uruk Period |

| Followed by | Early Dynastic Period |

History of research

In the early 1900s, clay tablets with an archaic form of the Sumerian cuneiform script began to appear in the antiquities market. A collection of 36 tablets was bought by the German excavators of Shuruppak (Tell Fara) in 1903. While they thought that the tablets came from Tell Jemdet Nasr, it was later shown that they probably came from nearby Tell Uqair. Similar tablets were offered for sale by a French antiquities dealer in 1915, and these were again reported to have come from Tell Jemdet Nasr. Similar tablets, together with splendidly painted monochrome and polychrome pottery, were also shown by local Arabs in 1925 to the Assyriologist Stephen Herbert Langdon, then director of the excavations at Tell al-Uhaymir. The Arabs told Langdon the finds came from Jemdet Nasr, a site some 26 kilometres (16 mi) northeast of Tell al-Uhaymir. Langdon was sufficiently impressed, visited the site and started excavations in 1926. He uncovered a large mudbrick building containing more of the distinctive pottery and a collection of 150 to 180 clay tablets bearing the proto-cuneiform script.

The importance of these finds was realized immediately and the Jemdet Nasr Period (named after the eponymous type site) was officially defined at a conference in Baghdad in 1930, where at the same time both the Uruk and Ubaid periods had been defined.[1] It has later been shown that some of the material culture that was initially thought to be unique for the Jemdet Nasr Period also occurred during the preceding Uruk Period and the subsequent Early Dynastic Period. Nevertheless, it is generally believed that the Jemdet Nasr Period is still sufficiently distinct in its material culture as well as its socio-cultural characteristics to be recognized as a separate period. Since the first excavations at Tell Jemdet Nasr, the Jemdet Nasr Period has been found at numerous other archaeological sites across much of south-central Iraq, including Abu Salabikh, Shuruppak, Khafajah, Nippur, Tell Uqair, Ur, and Uruk.[2]

Dating and periodization

Older scientific literature often used 3200–3000 BC as the beginning and end dates of the Jemdet Nasr Period. The period is nowadays dated from 3100–2900 BC based on radiocarbon dating.[3][4][5][6] The Jemdet Nasr Period is contemporary with the early Ninevite V Period of Upper Mesopotamia and the Proto-Elamite Period of Iran, and shares with these two periods characteristics such as an emerging bureaucracy and inequality.[7]

Defining characteristics

The hallmark of the Jemdet Nasr Period is its distinctive painted monochrome and polychrome pottery. Designs are both geometric and figurative; the latter displaying trees and animals such as birds, fish, goats, scorpions, and snakes. Nevertheless, this painted pottery makes up only a small percentage of the total assemblage and at various sites it has been found in archaeological contexts suggesting that it was associated with high-status individuals or activities. At the site of Jemdet Nasr, the painted pottery was found exclusively in the settlement's large central building, which is thought to have played a role in the administration of many economic activities. Painted Jemdet Nasr Period pots were found in similar contexts at Tell Fara and Tell Gubba, both in the Hamrin Mountains.[8]

Apart from the distinctive pottery, the period is known as one of the formative stages in the development of the cuneiform script. The oldest clay tablets come from Uruk and date to the late fourth millennium BC, slightly earlier than the Jemdet Nasr Period. By the time of the Jemdet Nasr Period, the script had already undergone a number of significant changes. It originally consisted of pictographs, but by the time of the Jemdet Nasr Period it was already adopting simpler and more abstract designs. It is also during this period that the script acquired its iconic wedge-shaped appearance.[9]

While the language in which these tablets were written cannot be identified with certainty, it is thought to have been Sumerian.[10] The texts deal without exception with administrative matters such as the rationing of foodstuffs or listing objects and animals. Literary genres like hymns and king lists, which become very popular later in Mesopotamian history, are absent. Two different counting systems were in use: a sexagesimal system for animals and humans, for example, and a bisexagesimal system for things like grain, cheese, and fresh fish.[11] Contemporary archives have been found at Tell Uqair, Tell Khafajah, and Uruk.[12]

Society in the Jemdet Nasr Period

The centralized buildings, administrative cuneiform tablets and cylinder seals from sites like Jemdet Nasr suggest that settlements of this period were very organized, with a central administration regulating all aspects of the economy, from crafts to agriculture to the rationing of foodstuffs.

The economy seems to have been primarily concerned with subsistence based on agriculture and sheep-and-goat pastoralism and small-scale trade. Very few precious stones or exotic trade goods have been found at sites of this period. However, the homogeneity of the pottery across the southern Mesopotamian plain suggests intensive contacts and trade between settlements. This is strengthened by the find of a sealing at Jemdet Nasr that lists a number of cities that can be identified, including Ur, Uruk, and Larsa.[13]

Artifacts

- Painted ceramic vessel from the Jemdet Nasr period, found at Khafajah. Museum of the Oriental Institute, Chicago.

Cup with nude heroes. Jemdet Nasr to Pre-Dynastic period, 3000-2600 BC.

Cup with nude heroes. Jemdet Nasr to Pre-Dynastic period, 3000-2600 BC.- Reverse of the same cup with Nude Hero, Bulls and Lions, Tell Agrab, Jamdat Nasr to Early Dynastic period, 3000-2600 BC.

Jemdet Nasr Period bull statue from limestone (found in Uruk, Iraq.)

Jemdet Nasr Period bull statue from limestone (found in Uruk, Iraq.)- Djemdet Nasr stone bowl, once inlaid with mother-of-pearl, red paste, and bitumen.

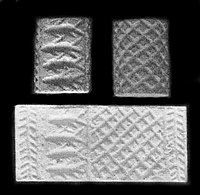

Cylinder seals, Djemdet Nasr 3.

Cylinder seals, Djemdet Nasr 3. Late uruk/ Jeldet Nasr period cylinder seal (3350-2900 BC).

Late uruk/ Jeldet Nasr period cylinder seal (3350-2900 BC). Late uruk/ Jeldet Nasr period cylinder seal (3350-2900 BC).

Late uruk/ Jeldet Nasr period cylinder seal (3350-2900 BC). Late uruk/ Jeldet Nasr period cylinder seal (3350-2900 BC).

Late uruk/ Jeldet Nasr period cylinder seal (3350-2900 BC). Late uruk/ Jeldet Nasr period cylinder seal (3350-2900 BC).

Late uruk/ Jeldet Nasr period cylinder seal (3350-2900 BC). Jemdet Nasr-style Mesopotamian cylinder seal, from Grave 7304 Cemetery 7000 at Naqada, Egypt, Naqada II period. This is an example of early Egypt-Mesopotamia relations.[14]

Jemdet Nasr-style Mesopotamian cylinder seal, from Grave 7304 Cemetery 7000 at Naqada, Egypt, Naqada II period. This is an example of early Egypt-Mesopotamia relations.[14]

References

- Matthews 2002, pp. 1–7

- Matthews 2002, p. 20

- Pollock 1992, p. 299

- Pollock 1999, p. 2

- Postgate 1992, p. 22

- van de Mieroop 2007, p. 19

- Matthews 2002, p. 37

- Matthews 2002, pp. 20–21

- Woods 2010, pp. 36–37

- Woods 2010, pp. 44–45

- Woods 2010, p. 39

- Woods 2010, p. 35

- Matthews 2002, pp. 33–37

- Kantor, Helene J. (1952). "Further Evidence for Early Mesopotamian Relations with Egypt". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 11 (4): 239–250. ISSN 0022-2968.

Bibliography

- Matthews, Roger (2002), Secrets of the dark mound: Jemdet Nasr 1926-1928, Iraq Archaeological Reports, 6, Warminster: BSAI, ISBN 0-85668-735-9

- Pollock, Susan (1992), "Bureaucrats and managers, peasants and pastoralists, imperialists and traders: Research on the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods in Mesopotamia", Journal of World Prehistory, 6 (3): 297–336, doi:10.1007/BF00980430

- Pollock, Susan (1999), Ancient Mesopotamia. The Eden that never was, Case Studies in Early Societies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-57568-3

- Postgate, J.N. (1992), Early Mesopotamia. Society and economy at the dawn of history, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-11032-7

- van de Mieroop, M. (2007), A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000-323 BC, Malden: Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-22552-8

- Woods, Christopher (2010), "The earliest Mesopotamian writing", in Woods, Christopher (ed.), Visible language. Inventions of writing in the ancient Middle East and beyond (PDF), Oriental Institute Museum Publications, 32, Chicago: University of Chicago, pp. 33–50, ISBN 978-1-885923-76-9