2006 Canadian federal election

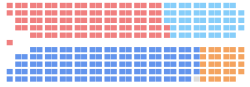

The 2006 Canadian federal election (more formally, the 39th General Election) was held on January 23, 2006, to elect members of the House of Commons of Canada of the 39th Parliament of Canada. The Conservative Party won the greatest number of seats − 40.3% of seats, or 124 out of 308, up from 99 seats in 2004 — and 36.3% of votes, up from 29.6% in the 2004 election.[1]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

308 seats in the House of Commons 155 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 64.7% ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

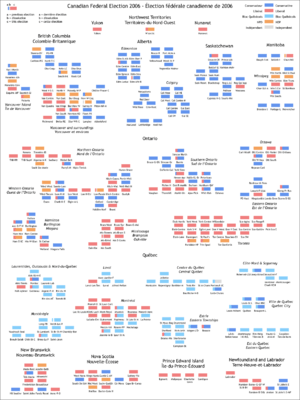

Popular vote by province, with graphs indicating the number of seats won. As this is an FPTP election, seat totals are not determined by popular vote by province but instead via results by each riding. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The election resulted in a minority government led by the Conservative Party with Stephen Harper becoming the 22nd Prime Minister of Canada. By proportion of seats, this was Canada's smallest minority government since Confederation. Despite this, it was the longest-serving minority government overall.

Voter turnout was 64.7%.[2]

Elections Canada later investigated improper election spending by the Conservative Party, which became widely known as the In and Out scandal. In 2011, charges against senior Conservatives were dropped in a plea deal that saw the party and its fundraising arm plead guilty and receive the maximum possible fines, totaling $52,000.[3]

Cause of the election

This unusual winter general election was caused by a motion of no confidence passed by the House of Commons on November 28, 2005, with Canada's three opposition parties contending that the Liberal government of Prime Minister Paul Martin was corrupt.[4] The following morning Martin met with Governor General Michaëlle Jean, who then dissolved parliament,[5] summoned the next parliament,[6] and ordered the issuance of writs of election.[7] The last set January 23, 2006, as election day and February 13 as the date for return of the writs. The campaign was almost eight weeks in length, the longest in two decades, in order to allow time for the Christmas and New Year holidays.

Recent political events, most notably testimony to the Gomery Commission investigating the sponsorship scandal, significantly weakened the Liberals (who, under Martin, had formed the first Liberal minority government since the Trudeau era) by allegations of criminal corruption in the party. The first Gomery report, released November 1, 2005, had found a "culture of entitlement" to exist within the Government. Although the next election was not legally required until 2009, the opposition had enough votes to force the dissolution of Parliament earlier. While Prime Minister Martin had committed in April 2005 to dissolve Parliament within a month of the tabling of the second Gomery Report (which was released on schedule on February 1, 2006), all three opposition parties—the Conservatives, Bloc Québécois, and New Democratic Party (NDP)—and three of the four independents decided that the issue at hand was how to correct the Liberal corruption, and the motion of non-confidence passed 171–133.

Results

The election was held on January 23, 2006. The first polls closed at 7:00 p.m. ET (0000 UTC); Elections Canada started to publish preliminary results on its website at 10:00 p.m. ET as the last polls closed. Harper was reelected in Calgary Southwest, which he has held since 2002, ensuring that he had a seat in the new parliament. Shortly after midnight (ET) that night, incumbent Prime Minister Paul Martin conceded defeat, and announced that he would resign as leader of the Liberal Party. He continued to sit as a Member of Parliament representing LaSalle—Émard, the Montreal-area riding he had held since 1988, until his retirement in 2008.

At 9:30 a.m. on January 24, Martin informed Governor General Michaëlle Jean that he would not form a government and intended to resign as Prime Minister. It was announced a month later that there would be a Liberal leadership convention later in the year, during which Stéphane Dion won the leadership of the Liberal Party. Later that day, at 6:45 p.m., Jean invited Harper to form a government. Martin formally resigned and Harper was formally appointed and sworn in as Prime Minister on February 6.[8]

Overall results

The elections resulted in a Conservative minority government with 124 seats in parliament with a Liberal opposition and a strengthened NDP. In his speech following the loss, Martin stated he would not lead the Liberal Party of Canada in another election. Preliminary results indicated that 64.9% of registered voters cast a ballot, a notable increase over 2004's 60.9%.[9]

The NDP won new seats in British Columbia and Ontario as their overall popular vote increased 2% from 2004. The Bloc managed to win almost as many seats as in 2004 despite losing a significant percentage of the vote. Most of the Conservatives' gains were in rural Ontario and Quebec as they took a net loss in the west, but won back the only remaining Liberal seat in Alberta. The popular vote of the Conservatives and Liberals were almost the mirror image of 2004, though the Conservatives were not able to translate this into as many seats as the Liberals did in 2004.

A judicial recount was automatically scheduled in the Parry Sound—Muskoka riding, where early results showed Conservative Tony Clement only 21 votes ahead of Liberal Andy Mitchell, because the difference of votes cast between the two leading candidates was less than 0.1%. Clement was confirmed as the winner by 28 votes.[10]

Conservative candidate Jeremy Harrison, narrowly defeated by Liberal Gary Merasty in the Saskatchewan riding of Desnethé—Missinippi—Churchill River by 72 votes, alleged electoral fraud but decided not to pursue the matter. A judicial recount was ordered in the riding,[11] which certified Gary Merasty the winner by a reduced margin of 68 votes.[12]

| ↓ | ||||

| 124 | 103 | 51 | 29 | 1 |

| Conservative | Liberal | BQ | NDP | I |

| Party | Party leader | Candi- dates |

Seats | Popular vote | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Dissol. | 2006 | % Change | # | % | Change | ||||||

| Conservative | Stephen Harper | 308 | 99 | 98 | 124 | +26.3% | 5,374,071 | 36.27% | +6.64pp | |||

| Liberal | Paul Martin | 308 | 135 | 133 | 103 | -23.7% | 4,479,415 | 30.23% | -6.50pp | |||

| Bloc Québécois | Gilles Duceppe | 75 | 54 | 53 | 51 | -5.6% | 1,553,201 | 10.48% | -1.90pp | |||

| New Democrats | Jack Layton | 308 | 19 | 18 | 29 | +52.6% | 2,589,597 | 17.48% | +1.71pp | |||

| Independents and no affiliation | 90 | 1 | 4 | 11 | - | 81,860 | 0.55% | -0.07pp | ||||

| Green | Jim Harris | 308 | - | - | - | 664,068 | 4.48% | +0.19pp | ||||

| Christian Heritage | Ron Gray | 45 | - | - | - | 28,152 | 0.19% | -0.11pp | ||||

| Progressive Canadian | Tracy Parsons | 25 | - | - | - | 14,151 | 0.10% | +0.02pp | ||||

| Marijuana | Blair Longley | 23 | - | - | - | 9,171 | 0.06% | -0.18pp | ||||

| Marxist-Leninist | Sandra L. Smith | 69 | - | - | - | 8,980 | 0.06% | +0.00pp | ||||

| Canadian Action | Connie Fogal | 34 | - | - | - | 6,102 | 0.04% | -0.02pp | ||||

| Communist | Miguel Figueroa | 21 | - | - | - | 3,022 | 0.02% | -0.01pp | ||||

| Libertarian | Jean-Serge Brisson | 10 | - | - | - | 3,002 | 0.02% | +0.01pp | ||||

| First Peoples National | Barbara Wardlaw | 5 | * | - | - | * | 1,201 | 0.0081% | * | |||

| Western Block | Doug Christie | 4 | * | - | - | * | 1,094 | 0.0074% | * | |||

| Animal Alliance | Liz White | 1 | * | - | - | * | 72 | 0.00049% | * | |||

| Vacant | 2 | |||||||||||

| Total | 1634 | 308 | 308 | 308 | ±0.0% | 14,817,159 | 100% | |||||

| Source: Elections Canada | ||||||||||||

Notes:

- Official candidate nominations closed January 2, 2006. Candidate totals cited above are based on official filings. Nominations were official on January 5, 2006.

- "% change" refers to change from previous election

- * indicates the party did not contest in the previous election.

- 1 André Arthur was elected as an independent candidate in the Quebec City-area riding of Portneuf—Jacques-Cartier. He personally won 20,158 votes.

Vote and seat summaries

Results by province

| Party name | BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | NS | PE | NL | NU | NT | YT | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Seats: | 17 | 28 | 12 | 8 | 40 | 10 | 3 | 3 | - | 3 | - | - | - | 124 | |

| Vote: | 37.3 | 65.0 | 48.9 | 42.8 | 35.1 | 24.6 | 35.7 | 29.69 | 33.4 | 42.67 | 29.6 | 19.8 | 23.67 | 36.25 | ||

| Liberal | Seats: | 9 | - | 2 | 3 | 54 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 1 | - | 1 | 103 | |

| Vote: | 27.6 | 15.3 | 22.4 | 26.0 | 39.9 | 20.7 | 39.2 | 37.15 | 52.5 | 42.82 | 39.1 | 34.9 | 48.52 | 30.2 | ||

| Bloc Québécois | Seats: | 51 | 51 | |||||||||||||

| Vote: | 42.1 | 10.5 | ||||||||||||||

| New Democrat | Seats: | 10 | - | - | 3 | 12 | - | 1 | 2 | - | - | - | 1 | - | 29 | |

| Vote: | 28.6 | 11.6 | 24.0 | 25.4 | 19.4 | 7.5 | 21.9 | 29.84 | 9.6 | 13.58 | 17.6 | 42.1 | 23.85 | 17.5 | ||

| Green | Vote: | 5.3 | 6.5 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 4.7 | 4.0 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.9 | 0.9 | 5.9 | 2.1 | 4.0 | 4.5 | |

| Independent / No affiliation | Seats: | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| Vote: | 0.9 | 0.1 | ||||||||||||||

| Total seats: | 36 | 28 | 14 | 14 | 106 | 75 | 10 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 308 | ||

Notes

^ David Emerson, elected on January 23 as a Liberal in the British Columbia riding of Vancouver Kingsway, changed parties on February 6 to join the Conservatives before the new Parliament had taken office. He is reflected here as a Liberal.

^ André Arthur was elected as an independent candidate in the Quebec riding of Portneuf—Jacques-Cartier.

10 closest ridings

- Parry Sound—Muskoka, ON: Tony Clement (Cons) def. Andy Mitchell (Lib) by 28 votes

- Desnethé—Missinippi—Churchill River, SK: Gary Merasty (Lib) def. Jeremy Harrison (Cons) by 73 votes

- Winnipeg South, MB: Rod Bruinooge (Cons) def. Reg Alcock (Lib) by 111 votes

- Glengarry—Prescott—Russell, ON: Pierre Lemieux (Cons) def. René Berthiaume (Lib) by 203 votes

- Louis-Hébert, QC: Luc Harvey (Cons) def. Roger Clavet (BQ) by 231 votes

- St. Catharines, ON: Rick Dykstra (Cons) def. Walt Lastewka (Lib) by 244 votes

- Tobique—Mactaquac, NB: Mike Allen (Cons) def. Andy Savoy (Lib) by 336 votes

- Thunder Bay—Superior North, ON: Joe Comuzzi (Lib) def. Bruce Hyer (NDP) by 408 votes

- West Nova, NS: Robert Thibault (Lib) def. Greg Kerr (Cons) by 511 votes

- Brant, ON: Lloyd St. Amand (Lib) def. Phil McColeman (Cons) by 582 votes

Results by electoral district

|

|

|

|

Parties

Most observers believed only the Liberals and the Conservatives were capable of forming a government in this election, although Canadian political history is not without examples of wholly unexpected outcomes, such as Ontario's provincial election in 1990. However, with the exception of the Unionist government of 1917 (which combined members of both the Conservatives and the Liberals), at the Federal stage, only Liberals or Conservatives have formed government. With the end of the campaign at hand, pollsters and pundits placed the Conservatives ahead of the Liberals.

Prime Minister Paul Martin's Liberals hoped to recapture their majority, and this appeared likely at one point during the campaign; but it would have required holding back Bloc pressure in Quebec plus picking up some new seats there while also gaining seats in English Canada, most likely in rural Ontario and southwestern British Columbia. Towards the end of the campaign, even high-profile Liberals were beginning to concede defeat, and the best the Liberals could have achieved was a razor-thin minority.

Stephen Harper's Conservatives succeeded in bringing their new party into power in Canada. While continuing weaknesses in Quebec and urban areas rightfully prompted most observers to consider a Conservative majority government to be mathematically difficult to achieve, early on, Harper's stated goal was to achieve one nonetheless. Though the Conservatives were ahead of the Liberals in Quebec, they remained far behind the Bloc Québécois, and additional gains in rural and suburban Ontario would have been necessary to meet Stephen Harper's goal. The polls had remained pretty well static over the course of December, with the real shift coming in the first few days of the New Year. That is when the Conservatives took the lead and kept it for the rest of the campaign.

Harper started off the first month of the campaign with a policy-per-day strategy, which included a GST reduction and a child-care allowance. The Liberals opted to hold any major announcements until after the Christmas holidays; as a result, Harper dominated media coverage for the first weeks of the campaign and was able to define his platform and insulate it from expected Liberal attacks. On December 27, 2005, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police announced it was investigating allegations that Liberal Finance Minister Ralph Goodale's office had engaged in insider trading before making an important announcement on the taxation of income trusts. The RCMP indicated that they had no evidence of wrongdoing or criminal activity from any party associated with the investigation, including Goodale. However, the story dominated news coverage for the following week and prevented the Liberals from making their key policy announcements, allowing the Conservatives to refocus their previous attacks about corruption within the Liberal party. The Conservatives soon found themselves leading in the polls. By early January, they made a major breakthrough in Quebec, pushing the Liberals to second place.

As their lead solidified, media coverage of the Conservatives was much more positive, while Liberals found themselves increasingly criticized for running a poor campaign and making numerous gaffes.[13]

The NDP has claimed that last minute tactical voting cost them several seats last time, as left-of-centre voters moved to the Liberals so that they could prevent a Harper-led government. Jack Layton avoided stating his party's goal was to win the election outright, instead calling for enough New Democrats to be elected to hold the balance of power in a Liberal or Conservative minority government. Political commentators have long argued that the NDP's main medium-term goal is to serve as junior partners to the Liberals in Canada's first-ever true coalition government. NDP leader Jack Layton was concerned last time over people voting Liberal so that they could avoid a Conservative government. Over the course of the last week of the campaign, Jack Layton called on Liberal voters disgusted with the corruption to "lend" their votes to the NDP to elect more NDP members to the House and hold the Conservatives to a minority.

The Bloc Québécois had a very successful result in the 2004 election, with the Liberals reduced to the core areas of federalist support in portions of Montreal and the Outaouais. Oddly enough, this meant that there were comparatively few winnable Bloc seats left—perhaps eight or so—for the party to target. With provincial allies the Parti Québécois widely tipped to regain power in 2007, a large sovereigntist contingent in the House could play a major role in reopening the matter of Quebec independence. The Bloc Québécois only runs candidates in the province of Quebec. However, Gilles Duceppe's dream of winning 50%+ of the popular vote was dashed when the polls broke after the New Year, and the Conservatives became a real threat to that vision in Quebec.

In addition to the four sitting parties, the Green Party of Canada ran candidates in all 308 federal ridings for the second consecutive election. Though the Greens had been an official party since the 1984 election, this campaign was the first in which they had stable financial support with which to campaign. After a breakthrough in the 2004 election, they exceeded the minimum 2% of the popular vote to receive federal funding. Supporters and sympathisers criticize that the party were not invited to the nationally televised debates even with its official status. The party has occasionally polled as high as 19% in British Columbia and 11% nationwide. Critics of the Green Party contend that, by drawing away left-of-centre votes, the Green Party actually assists the Conservative Party in some ridings. The Greens deny this.[14]

Other parties are listed in the table of results above.

Events during the 38th Parliament

An early election seemed likely because the 2004 federal election, held on June 28, 2004, resulted in the election of a Liberal minority government. In the past, minority governments have had an average lifespan of a year and a half. Some people considered the 38th parliament to be particularly unstable. It involved four parties, and only very implausible ideological combinations (e.g., Liberals + Conservatives; Liberals + BQ; Conservatives + BQ + NDP) could actually command a majority of the seats, a necessity if a government is to retain power. From its earliest moments, there was some threat of the government falling as even the Speech from the Throne almost resulted in a non-confidence vote.

Brinkmanship in the spring of 2005

The Liberal government came close to falling when testimony from the Gomery Commission caused public opinion to move sharply against the government. The Bloc Québécois were eager from the beginning to have an early election. The Conservatives announced they had also lost confidence in the government's moral authority. Thus, during much of spring 2005, there was a widespread belief that the Liberals would lose a confidence vote, prompting an election taking place in the spring or summer of 2005.

In a televised speech on April 21, Martin promised to request a dissolution of Parliament and begin an election campaign within 30 days of the Gomery Commission's final report. The release date of that report would later solidify as February 1, 2006; Martin then clarified that he intended to schedule the election call so as to have the polling day in April 2006.

Later that week, the NDP, who had initially opposed the budget, opted to endorse Martin's proposal for a later election. The Liberals agreed to take corporate tax cuts out of the budget on April 26 in exchange for NDP support on votes of confidence, but even with NDP support the Liberals still fell three votes short of a majority. However, a surprise defection of former Conservative leadership candidate Belinda Stronach to the Liberal party on May 17 changed the balance of power in the House. Independents Chuck Cadman and Carolyn Parrish provided the last two votes needed for the Liberals to win the budget vote.

The deal turned out to be rather unnecessary, as the Conservatives opted to ensure the government's survival on the motion of confidence surrounding the original budget, expressing support to the tax cuts and defence spending therein. When Parliament voted on second reading and referral of the budget and the amendment on May 19, the previous events kept the government alive. The original budget bill, C-43, passed easily, as expected, but the amendment bill, C-48, resulted in an equality of votes, and the Speaker of the House broke the tie to continue the parliament. The government never got as close to falling after that date. Third reading of Bill C-48 was held late at night on an unexpected day, and several Conservatives being absent, the motion passed easily, guaranteeing there would be no election in the near future.

Aftermath of the first Gomery report

On November 1, John Gomery released his interim report, and the scandal returned to prominence. Liberal support again fell, with some polls registering an immediate ten percent drop. The Conservatives and Bloc thus resumed their push for an election before Martin's April date. The NDP stated that their support was contingent on the Liberals agreeing to move against the private provision of healthcare. The Liberals and NDP failed to come to an agreement, however, and the NDP joined the two other opposition parties in demanding an election.

However, the Liberals had intentionally scheduled the mandatory "opposition days" (where a specified opposition party controls the agenda) on November 15 (Conservative), November 17 (Bloc Québécois) and November 24 (NDP). These days meant that any election would come over the Christmas season, an unpopular idea. Following negotiations between the opposition parties, they instead issued an ultimatum to the Prime Minister to call an election immediately after the Christmas holidays or face an immediate non-confidence vote which would prompt a holiday-spanning campaign.

To that end, the NDP introduced a parliamentary motion demanding that the government drop the writ in January 2006 for a February 13 election date; however, only the prime minister has the authority to advise the Governor General on an election date, the government was therefore not bound by the NDP's motion. Martin had indicated that he remained committed to his April 2006 date, and would disregard the motion, which the opposition parties managed to pass, as expected, on November 21 by a vote of 167–129.

The three opposition leaders had agreed to delay the tabling of the no-confidence motion until the 24th, to ensure that a conference between the government and aboriginal leaders scheduled on the 24th would not be disrupted by the campaign. Parliamentary procedure dictated that the vote be deferred until the 28th. Even if the opposition hadn't put forward the non-confidence motion, the government was still expected to fall—there was to have been a vote on supplementary budget estimates on December 8, and if it had been defeated, loss of Supply would have toppled the Liberals.

Conservative leader Stephen Harper, the leader of the Opposition, introduced a motion of no confidence on November 24, which NDP leader Jack Layton seconded. The motion was voted upon and passed in the evening of November 28, with all present MPs from the NDP, Bloc Québécois, and Conservatives and 3 Independents (Bev Desjarlais, David Kilgour and Pat O'Brien), voting with a combined strength of 171 votes for the motion and 132 Liberals and one Independent (Carolyn Parrish) voting against. One Bloc Québécois MP was absent from the vote. It is the fifth time a Canadian government has lost the confidence of Parliament, but the first time this has happened on a straight motion of no confidence. The four previous instances have been due to loss of supply or votes of censure.

Martin visited Governor General Michaëlle Jean the following morning, where he formally advised her to dissolve Parliament and schedule an election for January 23. In accordance with Canadian constitutional practice, she consented (such a request has only been turned down once in Canadian history), officially beginning an election campaign that had been simmering for months.

Early on in the campaign, polls showed the Liberals with a solid 5–10 point lead over the Conservatives, and poised to form a strong minority government at worst. Around Christmas, after reports of an RCMP investigation into allegations of insider trading within the Finance department, this situation changed dramatically, leading to the opposition parties to consistently attack the Liberals on corruption. Almost at the same time, the Boxing Day shooting, an unusually violent gun fight between rival gangs on December 26 in downtown Toronto (resulting in the death of 15-year-old Jane Creba, an innocent bystander), may have swayed some Ontario voters to support the more hardline CPC policies on crime. The Conservatives enjoyed a fairly significant lead in polls leading up to the election, but the gap narrowed in the last few days.

Issues

Several issues—some long-standing (notably fiscal imbalance, the gun registry, abortion, and Quebec sovereigntism), others recently brought forth by media coverage (including redressing the Chinese Canadian community for long-standing wrongs that forced both parties to back-track on their position in the national and ethnic media, particularly in key British Columbia and Alberta ridings), or court decisions (the sponsorship scandal, same-sex marriages, income trusts, or Canada–United States relations)—took the fore in debate among the parties and also influenced aspects of the parties' electoral platforms.

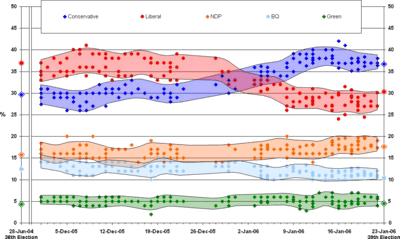

Opinion polls

Prior to and during the election campaign, opinion polling showed variable support for the governing Liberals and opposition Conservatives. In November 2005, the first report by Justice John Gomery was released to the public; subsequently, poll numbers for the Liberals again dropped. Just days later, polling showed the Liberals were already bouncing back; upon the election call, the Liberals held a small lead over the Conservatives and maintained this for much of December. Renewed accusations of corruption and impropriety at the end of 2005 – amid Royal Canadian Mounted Police criminal probes of possible government leaks regarding income trust tax changes and advertising sponsorships – led to an upswing of Conservative support again and gave them a lead over the Liberals, portending a change in government. Ultimately this scandal was linked to a blackberry exchange to a banking official by Liberal candidate Scott Brison. Polling figures for the NDP increased slightly, while Bloc figures experienced a slight dip; figures for the Green Party did not change appreciably throughout the campaign.

Exit poll

An exit poll was carried out by Ipsos Reid polling firm. The poll overestimated the NDP's support and underestimated the Liberal's support. Here is a results breakdown by demographics:[15]

| 2006 vote by demographic subgroup (Ipsos Reid Exit Polling) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic subgroup | LPC | CPC | NDP | GPC | BQ | Other | % of voters | |||

| Total vote | 26 | 36 | 21 | 5 | 12 | 1 | 100 | |||

| Ideological self-placement | ||||||||||

| Liberals | 54 | 9 | 25 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 30 | |||

| Moderates | 17 | 31 | 24 | 6 | 19 | 1 | 51 | |||

| Conservatives | 3 | 88 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 20 | |||

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Men | 25 | 38 | 18 | 5 | 12 | 1 | 49 | |||

| Women | 26 | 33 | 23 | 5 | 11 | 1 | 51 | |||

| Immigrant | ||||||||||

| Born in Canada | 25 | 36 | 21 | 5 | 13 | 1 | 89 | |||

| Born in another country | 34 | 36 | 21 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 11 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Single | 26 | 25 | 24 | 7 | 17 | 1 | 21 | |||

| Married | 26 | 44 | 18 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 52 | |||

| Domestic Partnership | 21 | 26 | 24 | 6 | 21 | 1 | 13 | |||

| Widowed | 28 | 38 | 24 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Divorsed | 26 | 30 | 23 | 5 | 14 | 1 | 7 | |||

| Separated | 26 | 32 | 24 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Don't know/Won't say | 23 | 22 | 29 | 6 | 18 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Religious identity | ||||||||||

| Catholic | 24 | 30 | 15 | 4 | 25 | 1 | 36 | |||

| Protestant or Other Christian | 26 | 48 | 20 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 37 | |||

| Muslim | 49 | 15 | 28 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Jewish | 52 | 25 | 15 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Hindu | 43 | 30 | 21 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Sikh | 39 | 16 | 40 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Other religion | 26 | 26 | 33 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 5 | |||

| None | 25 | 26 | 28 | 8 | 12 | 1 | 19 | |||

| Don't know/Refused | 29 | 27 | 26 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Religious service attendance | ||||||||||

| More than once a week | 18 | 63 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |||

| Once a week | 25 | 51 | 15 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 10 | |||

| A few times a month | 30 | 41 | 20 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 6 | |||

| Once a month | 29 | 36 | 23 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 2 | |||

| A few times a year | 29 | 35 | 19 | 4 | 12 | 1 | 16 | |||

| At least once a year | 24 | 31 | 19 | 5 | 21 | 1 | 12 | |||

| Not at all | 25 | 31 | 13 | 6 | 14 | 1 | 48 | |||

| Don't know/refused | 25 | 31 | 26 | 5 | 10 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Age | ||||||||||

| 18–34 years old | 22 | 29 | 25 | 7 | 17 | 1 | 27 | |||

| 35-54 years old | 25 | 37 | 20 | 5 | 11 | 1 | 41 | |||

| 55 and older | 29 | 41 | 17 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 31 | |||

| Age by gender | ||||||||||

| Men 18–34 years old | 23 | 30 | 23 | 7 | 16 | 1 | 14 | |||

| Men 35-54 years old | 25 | 39 | 18 | 6 | 12 | 1 | 21 | |||

| Men 55 and older | 26 | 45 | 16 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 14 | |||

| Women 18–34 years old | 21 | 27 | 26 | 7 | 18 | 1 | 13 | |||

| Women 35-54 years old | 25 | 34 | 23 | 5 | 11 | 1 | 21 | |||

| Women 55 and older | 32 | 36 | 21 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 17 | |||

| Sexual orientation | ||||||||||

| LGBT | 36 | 8 | 33 | 6 | 17 | 0 | 4 | |||

| Non-LGBT | 25 | 37 | 20 | 5 | 12 | 1 | 95 | |||

| Don't know/Refused | 23 | 24 | 21 | 11 | 10 | 3 | 1 | |||

| First time voter | ||||||||||

| First time voter | 24 | 29 | 27 | 7 | 12 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Everyone else | 26 | 36 | 20 | 5 | 12 | 1 | 95 | |||

| Education | ||||||||||

| Primary school or less | 27 | 39 | 14 | 2 | 14 | 4 | 0 | |||

| Some High school | 23 | 38 | 19 | 4 | 14 | 1 | 5 | |||

| High school | 22 | 40 | 20 | 4 | 13 | 1 | 16 | |||

| Some CC/CEGEP/Trades school | 23 | 38 | 21 | 5 | 11 | 1 | 17 | |||

| CC/CEGEP/Trades school | 23 | 37 | 20 | 5 | 12 | 1 | 20 | |||

| Some University | 27 | 32 | 21 | 6 | 13 | 1 | 13 | |||

| University undergraduate degree | 29 | 30 | 21 | 7 | 12 | 1 | 18 | |||

| University graduate degree | 33 | 30 | 20 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 10 | |||

| Don't know/Won't say | 26 | 36 | 21 | 5 | 12 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| Smoker | 23 | 32 | 24 | 5 | 15 | 1 | 22 | |||

| Non-smoker | 26 | 37 | 20 | 5 | 11 | 1 | 17 | |||

| Employment | ||||||||||

| Employed full-time | 25 | 35 | 20 | 5 | 13 | 1 | 42 | |||

| Employed part-time | 24 | 35 | 23 | 5 | 11 | 1 | 9 | |||

| Self-employed | 27 | 39 | 17 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 10 | |||

| Homemaker | 22 | 43 | 20 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Student | 25 | 20 | 29 | 8 | 17 | 1 | 7 | |||

| Retired | 30 | 41 | 17 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 17 | |||

| Currently unemployed | 23 | 30 | 25 | 7 | 13 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Other | 25 | 30 | 30 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Household income | ||||||||||

| Under $10K | 23 | 26 | 28 | 7 | 14 | 1 | 3 | |||

| $10K to $15K | 21 | 25 | 30 | 6 | 17 | 1 | 3 | |||

| $15K to $20K | 24 | 28 | 27 | 6 | 14 | 1 | 3 | |||

| $20K to $25K | 22 | 30 | 26 | 5 | 15 | 1 | 4 | |||

| $25K to $30K | 23 | 34 | 22 | 6 | 14 | 2 | 5 | |||

| $30K to $35K | 22 | 32 | 24 | 5 | 15 | 1 | 6 | |||

| $35K to $40K | 24 | 34 | 22 | 4 | 14 | 1 | 6 | |||

| $40K to $45K | 24 | 33 | 21 | 5 | 15 | 1 | 7 | |||

| $45K to $55K | 24 | 35 | 22 | 4 | 13 | 1 | 10 | |||

| $55K to $60K | 24 | 38 | 19 | 5 | 13 | 1 | 6 | |||

| $60K to $70K | 25 | 38 | 21 | 4 | 11 | 1 | 9 | |||

| $70K to $80K | 27 | 39 | 19 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 9 | |||

| $80K to $100K | 26 | 39 | 18 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 11 | |||

| $100K to $120K | 30 | 38 | 17 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 7 | |||

| $120K to $150K | 32 | 41 | 14 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 5 | |||

| $150K or more | 32 | 43 | 14 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Union membership | ||||||||||

| Union | 22 | 31 | 25 | 5 | 16 | 1 | 32 | |||

| Non-union | 27 | 38 | 19 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 68 | |||

| Home ownership | ||||||||||

| Own | 26 | 40 | 18 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 68 | |||

| Rent | 24 | 26 | 23 | 5 | 18 | 1 | 28 | |||

| Neither | 22 | 23 | 23 | 6 | 24 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Region | ||||||||||

| British Columbia and Yukon | 25 | 37 | 31 | 5 | n/a | 1 | 13 | |||

| Alberta, NWT and Nunavut | 14 | 65 | 14 | 7 | n/a | 1 | 10 | |||

| Saskatchewan and Manitoba | 22 | 44 | 28 | 5 | n/a | 2 | 7 | |||

| Ontario | 35 | 36 | 23 | 6 | n/a | 1 | 38 | |||

| Quebec | 15 | 23 | 10 | 4 | 47 | 1 | 25 | |||

| Atlantic Canada | 36 | 30 | 29 | 4 | n/a | 1 | 8 | |||

| CMA | ||||||||||

| Greater Vancouver | 30 | 33 | 30 | 5 | n/a | 1 | 5 | |||

| Greater Calgary | 14 | 66 | 11 | 9 | n/a | 0 | 3 | |||

| Greater Edmonton | 16 | 60 | 17 | 6 | n/a | 0 | 3 | |||

| Greater Toronto Area | 40 | 33 | 20 | 6 | n/a | 1 | 12 | |||

| National Capital Region | 27 | 40 | 19 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Greater Montreal | 20 | 17 | 11 | 5 | 47 | 1 | 12 | |||

| Rest of Canada | 24 | 37 | 23 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 58 | |||

| Community size | ||||||||||

| 1 Million plus | 31 | 25 | 19 | 5 | 19 | 1 | 27 | |||

| 500K to 1M | 20 | 46 | 18 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 18 | |||

| 100K to 500K | 30 | 31 | 28 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 14 | |||

| 10K to 100K | 24 | 38 | 22 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 21 | |||

| 1.5K to 10K | 22 | 41 | 19 | 5 | 11 | 2 | 15 | |||

| Under 1.5K | 19 | 43 | 18 | 5 | 13 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Factor most influencing choice of vote | ||||||||||

| The local candidate | 33 | 33 | 19 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 21 | |||

| The party leader | 27 | 37 | 21 | 1 | 13 | 0 | 17 | |||

| The party's stances on the issues | 23 | 36 | 21 | 7 | 13 | 1 | 61 | |||

| Issue regarded as most important | ||||||||||

| Healthcare | 27 | 23 | 33 | 3 | 13 | 1 | 15 | |||

| Corruption | 3 | 61 | 12 | 3 | 19 | 1 | 19 | |||

| Economy | 49 | 27 | 10 | 2 | 11 | 1 | 14 | |||

| Environment | 8 | 3 | 24 | 47 | 17 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Reducing taxes | 17 | 59 | 12 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 7 | |||

| Social programs | 27 | 13 | 45 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 11 | |||

| Abortion and/or gay marriage | 33 | 36 | 19 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 10 | |||

| Jobs | 24 | 27 | 16 | 2 | 23 | 1 | 4 | |||

| National Unity | 51 | 27 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | |||

| US-Canada relationship | 14 | 71 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Crime | 15 | 66 | 12 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 | |||

| Immigration | 29 | 45 | 18 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | |||

| The Atlantic Accord | 52 | 26 | 14 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Abortion position | ||||||||||

| Legal in all cases | 29 | 24 | 24 | 6 | 16 | 1 | 40 | |||

| Legal in most cases | 26 | 36 | 20 | 5 | 12 | 1 | 37 | |||

| Illegal in most cases | 17 | 58 | 15 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 13 | |||

| Illegal in all cases | 17 | 65 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Don't know | 25 | 42 | 20 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 6 | |||

| Gun ownership | ||||||||||

| Yes | 20 | 46 | 18 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 17 | |||

| No | 27 | 33 | 21 | 5 | 12 | 1 | 82 | |||

| Refused | 18 | 49 | 18 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 1 | |||

Candidates

The election involved the same 308 electoral districts as in 2004, except in New Brunswick, where the boundary between Acadie—Bathurst and Miramichi was ruled to be illegal. Many of the candidates were also the same: fewer incumbents chose to leave than if they had served a full term, and the parties have generally blocked challenges to sitting MPs for the duration of the minority government, although there had been some exceptions.

Gender breakdown of candidates

An ongoing issue in Canadian politics is the imbalance between the genders in selection by political parties of candidates. Although in the past some parties, particularly the New Democrats, have focused on the necessity of having equal gender representation in Parliament, no major party has ever nominated as many or more women than men in a given election. In 2006, the New Democrats had the highest percentage of female candidates (35.1%) of any party aside from the Animal Alliance, which only had one candidate, its leader, Liz White. The proportion of female New Democrats elected was greater than the proportion nominated, indicating female New Democrats were nominated in winnable ridings. 12.3% of Conservative candidates and 25.6% of Liberal candidates were female.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Campaign slogans

The parties' campaign slogans for the 2006 election:

| English slogan | French slogan | Literal English translation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Stand up for Canada | Changeons pour vrai | Let's change for real / for truth (pun) |

| Liberal | Choose your Canada | Un Canada à votre image | A Canada in your image |

| NDP | Getting results for people | Des réalisations concrètes pour les gens | Solid results for people |

| BQ | Thankfully, the Bloc is here! | Heureusement, ici, c'est le Bloc! | Fortunately, here, it's the Bloc! |

| Green | We can | Oui, nous pouvons | Yes, we can |

Endorsements

Target ridings

Incumbent MPs who did not run for re-election

Liberals

Independents |

Conservatives

New DemocratsBloquistes |

See also

Articles on parties' candidates in this election:

|

|

|

References

- Canada, Elections. "Important Information for the 39th General Election". Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- Pomfret, R. "Voter Turnout at Federal Elections and Referendums". Elections Canada Online. Elections Canada. Retrieved February 10, 2012.

- "Conservatives agree to plea deal in "in-and-out" scandal". Maclean's. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- Krauss, Clifford (November 29, 2005). "Liberal Party Loses Vote Of Confidence In Canada". New York Times.

- "Proclamation Dissolving Parliament" (PDF). Canada Gazette Part II. Government of Canada. 139 (6 Extra): 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 25, 2011.

- "Proclamation Summoning Parliament to Meet on February 20, 2006" (PDF). Canada Gazette Part II. Government of Canada. 139 (6 Extra): 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 25, 2011.

- "Proclamation Issuing Election Writs" (PDF). Canada Gazette Part II. Government of Canada. 139 (6 Extra): 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 25, 2011.

- Date for the Swearing-in of the Honourable Stephen Harper as the 22nd Prime Minister and of his Cabinet

- "Elections Canada - Electoral Districts". Enr.elections.ca. November 29, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- "Elections Canada - Judicial Recounts". Enr.elections.ca. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- "Seat was 'stolen,' defeated MP says". Archived from the original on May 27, 2007. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- "Liberals hold on to Saskatchewan riding after judicial recount". CBC News. February 10, 2006. Archived from the original on May 23, 2007.

- Whittington, Les (December 30, 2005). "'This is like a live grenade' for Liberal party" (Free). Toronto Star. Toronto Star Newspapers. Retrieved August 31, 2006.

- "The Greening of Canada". CTV.ca. January 19, 2006. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- Ipsos Reid Federal Election Exit Poll 2006, Wilfrid Laurier University, Ipsos Reid, LISPOP, 2006 (Available on odesi)

External links

| Wikinews has related news: |

- Election Prediction Project

- UBC Election Stock Market 2006

- Which party to vote for? (saplin.com) – Vote by issue quizz

- TrendLines Riding Projections (2004, 2006 & 2009)

- Predicting the 2006 Canadian Election

Government links

National media coverage

- First French Leaders' Debate Windows Media Video stream

- CTV News – Election 2006

- The Globe and Mail – Decision 2006

Humour

- 2006 Election Editorial Cartoon Gallery by Graeme MacKay of The Hamilton Spectator.

.jpg)

.jpg)