1952 Atlantic hurricane season

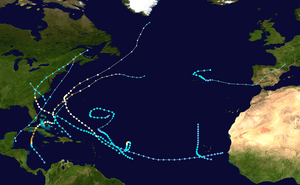

The 1952 Atlantic hurricane season was the last Atlantic hurricane season in which tropical cyclones were named using the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet. It was a near normal Atlantic hurricane season, although it was the least active since 1946.[1] The season officially started on June 15;[2] however, a pre-season unnamed storm formed on Groundhog Day, becoming the only storm on record in the month of February. The other six tropical cyclones were named using the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet, the first of which formed on August 18. The final storm of the season dissipated on October 28, two and a half weeks before the season officially ended on November 15.[3]

| 1952 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | February 3, 1952 |

| Last system dissipated | November 30, 1952 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Fox |

| • Maximum winds | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 934 mbar (hPa; 27.58 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 11 |

| Total storms | 11 |

| Hurricanes | 5 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 607 |

| Total damage | $13.75 million (1952 USD) |

| Related articles | |

Four of the tropical cyclones made landfall during the season, the first being the February tropical storm that crossed southern Florida. The first hurricane, named Able, struck South Carolina with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h), causing heavy damage near the coast and widespread power outages. It moved up most of the East Coast of the United States, leaving 3 deaths and widespread damage. As a developing tropical cyclone, Hurricane Charlie caused damaging flooding and landslides in southwest Puerto Rico. The final and strongest of the season, Hurricane Fox, struck Cuba with winds of 145 mph (233 km/h); it killed 600 people and left heavy damage, particularly to the sugar crop, reaching $10 million (1952 USD, $96.3 million 2020 USD).

Timeline

Systems

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | February 3 – February 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 990 mbar (hPa) |

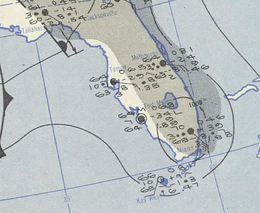

On February 2, a non-frontal low formed in the western Caribbean Sea two months after the end of the hurricane season. It moved quickly north-northwestward and acquired gale-force winds as it brushed the northern coast of Cuba. Early on February 3, the storm struck Cape Sable, Florida and quickly crossed the state.[4] The Miami National Weather Service office recorded a wind gust of 68 mph (110 km/h) during its passage.[5] The winds damaged windows and power lines,[6] catching residents and tourists off-guard.[7] The cyclone also dropped 2–4 inches (50–100 mm) of precipitation along its path, causing crop damage in Miami-Dade County.[5]

After leaving Florida, the storm briefly transitioned into a tropical storm on February 3, the only tropical or subtropical storm on record in the month. The storm continued rapidly northeastward, reaching peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h). On February 4 it evolved into an extratropical cyclone off the coast of North Carolina. Later that day, it passed over Cape Cod, and early on February 5 dissipated after crossing into Maine.[4] The storm caused scattered power outages and gusty winds across New England.[8]

Hurricane Able

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 18 – September 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) 980 mbar (hPa) |

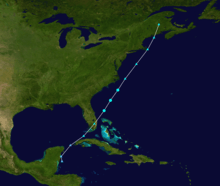

Over six months after the previous storm dissipated, a tropical depression developed just off the west coast of Africa on August 18. It moved generally west- to west-northwestward for much of its duration, intensifying into a tropical storm on August 24 east of the Lesser Antilles.[4] The next day, Hurricane Hunters confirmed the presence of Tropical Storm Able. Passing north of the islands, the storm attained hurricane status on August 27. On August 30, Able turned to the north-northwest due to an approaching cold front, and the next day made landfall near Beaufort, South Carolina as a Category 2 hurricane with peak winds of 100 mph (155 km/h).[1][4] The town was heavily damaged,[9] and was briefly isolated after winds downed power and telephone lines.[10] Across South Carolina, the hurricane caused two indirect deaths, as well as moderate damage totaling $2.2 million (1952 USD, $21.2 million 2020 USD).[1]

As Able turned north and northeastward over land, the winds quickly weakened to tropical storm force, although it retained gale force winds through North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland; this was due to remaining over the flat terrain east of the Appalachian Mountains, as well as retaining a plume of tropical moisture from its south. It left light damage in North Carolina, some of it due to a tornado.[1] In Maryland, heavy rainfall caused widespread flooding, which washed out the tracks of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad near Baltimore. In Ellicott City, Maryland, the rains flooded several houses, forcing families to evacuate.[11] Two tornadoes were also reported in the region, and damage in the Washington, D.C. area reached $500,000 (1952 USD, $4.81 million 2020 USD). Further northeast, the storm continued to produce heavy rainfall, causing flooding, as well as one indirect death in Pennsylvania. After moving through New England, Able dissipated on September 2 near Portland, Maine.[1]

Tropical Storm Three

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 27 – August 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

A cold front was located north of the Bahamas on August 26, with a broad area of cyclonic turning located east of northern Florida. Atmospheric pressures were falling in the region, and gale force winds were recorded by 12:00 UTC on August 27. Based on the structure, it is estimated that the frontal low developed into a tropical storm by 18:00 UTC that day. Ship reports in the region suggested peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h). There was very dry air on the west side of the system, unusual for August, and the radius of maximum winds was around 115 mi (185 km), suggesting that the structure could have been akin to a subtropical cyclone. The storm continued to the northwest, making landfall very near Myrtle Beach, South Carolina at 02:00 UTC on August 28. It spread rainfall across the Carolinas, later enhanced by Hurricane Able just days later, while cities reported winds of around 35 mph (55 km/h). The storm weakened over land and dissipated late on August 28 over eastern Kentucky.[12]

Hurricane Baker

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 31 – September 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) 969 mbar (hPa) |

The third tropical cyclone of the season developed on August 31 a short distance east of the northern Lesser Antilles.[4] Its presence was reported by a ship the next day that encountered rough seas and gale force winds. As a result, the Weather Bureau sent the Hurricane Hunters to investigate the system, which reported a strengthening hurricane moving northwestward.[1] Given the name Baker, the hurricane passed north of the Lesser Antilles, reaching peak winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) late on September 3.[4] For several days, the Hurricane Hunters reported similar winds, along with gusts up to 140 mph (230 km/h).[1]

With a large anticyclone located over the Ohio Valley, Baker turned to the northeast on September 5,[13] passing about halfway between Bermuda and North Carolina. The hurricane slowly weakened as it moved through the north Atlantic Ocean, just missing Newfoundland while maintaining winds of 80 mph (130 km/h).[4] Wind gusts on Avalon Peninsula reached 70 mph (110 km/h), and heavy fishing damage was reported in Lower Island Cove.[14] After affecting the island, Baker transitioned into an extratropical storm, which lasted another day before dissipating south of Greenland.[4]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 8 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 999 mbar (hPa) |

A dissipating cold front stalled across the northeastern Atlantic Ocean on September 7, northeast of the Azores. That day, a closed circulation developed and quickly became independent of the front. Based on a uniform thermal structure, as well as ship reports in the region of gale-force winds near the center, it is estimated that the system became a tropical storm early on September 8. Forming at a latitude of 42.0°N, this system is notable for being the northernmost forming tropical cyclone in the Atlantic hurricane database, dating back to 1851.[4]

The system moved west-southwestward, atypical for cyclones in that region during September. On September 9, the storm turned to the southeast, reaching estimated peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h), based on ship observations. Moving slowly through the northern Azores, the storm produced winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) along Terceira Island. It slowly weakened, and by late on September 10 the system degraded into a tropical depression. By the next day, the system was interacting with an approaching cold front, indicating that the depression had transitioned into an extratropical cyclone. Around 20:00 UTC, the storm moved ashore the southwestern tip of Portugal with gale-force winds. The storm turned to the northwest through the Iberian Peninsula, dissipating on September 14 over southwestern France.[12]

Hurricane Charlie

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 24 – September 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 958 mbar (hPa) |

On September 22, a tropical wave moved into the eastern Caribbean Sea,[1] spawning a tropical depression near Hispaniola early on September 24.[4] As it tracked west-northwestward, the low dropped heavy rainfall, peaking at 4.42 in (112 mm) in Christiansted, United States Virgin Islands, as well as 11.9 in (300 mm) in Garzas, Puerto Rico.[15] In Puerto Rico, the rains caused landslides that affected seven towns, notably Ponce, the island's second-largest city.[16] There, at least 14 buildings were destroyed.[17] The floods left more than 1,000 people homeless, 300 of whom took refuge in a Red Cross shelter.[16] Overall, the flooding on the island killed four people and left moderate damage of around $1 million (1952 USD, $9.63 million 2020 USD).[1]

After affecting Puerto Rico, the low continued to organize, and subsequently struck the Dominican Republic on September 23. The circulation became disrupted while crossing Hispaniola, although it reorganized near the Turks and Caicos Islands and became Tropical Storm Charlie before reaching those islands.[1] On September 25, Charlie attained hurricane status,[4], and due to its continued northwest motion, the Weather Bureau advised small craft to remain at port in the southeastern United States coast.[18] However, the hurricane turned to the north and northeast on September 26, during which the Hurricane Hunters recorded peak winds of 120 mph (195 km/h).[4] It briefly threatened Bermuda, prompting the United States Air Force to evacuate its fleet of airplanes from Kindley Air Force Base.[19] Charlie ultimately northwest of Bermuda, and later began weakening. On September 29 it turned eastward, and later that day transitioned into an extratropical cyclone. The remnants lasted two more days before dissipating 400 mi (640 km) southeast of Newfoundland.[1]

Tropical Storm Dog

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 24 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 998 mbar (hPa) |

On September 18, a tropical wave exited the west coast of Africa, which spawned a tropical cyclone east of the Lesser Antilles on September 24. The system quickly intensified and was given the name Dog. The storm moved northwestward for its entire duration. On September 26, Hurricane Hunters observed winds of 78 mph (126 km/h), with gusts to 100 mph (160 km/h), although they were unable to locate a closed center of circulation. Operationally, Dog was upgraded to hurricane status, but a reanalysis in 2015 downgraded the storm to a peak intensity of 70 mph (110 km/h), making it a strong tropical storm. Dog began weakening on September 27, and over the next few days the circulation lost its definition. On September 29, Dog weakened to a tropical depression, and dissipated the next day.[1][4] The Weather Bureau advised ships to avoid the storm, but overall Dog did not affect land.[19]

Tropical Storm Eight

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 25 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 1000 mbar (hPa) |

On September 24, a tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa. It is estimated that a closed circulation developed on the next day, suggesting the formation of a tropical depression. On September 26, Santiago island within Cape Verde recorded winds of 30 mph (45 km/h) as the system was passing to the southwest. A minimum pressure of 1,000 mbar (30 inHg) and ship reports of 35 mph (55 km/h) winds indicate that the system reached peak winds of 45 mph (75 km/h), or a minimal tropical storm. It turned to the north on September 27 and likely weakened, although observations were sparse. By September 30, the system lost its circulation and degenerated into an open trough.[12]

Hurricane Easy

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 6 – October 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 968 mbar (hPa) |

On October 6, a tropical depression formed about 700 mi (1,100 km) east of Antigua, near where Tropical Storm Dog developed a week prior. The depression proceeded northward, and was detected by the Hurricane Hunters on October 7 as a strengthening tropical storm. On that basis, the storm was named Easy. On October 8, the Hurricane Hunters observed a 26 mi (46 km) eye and wind gusts to 115 mph (185 km/h). On that basis, Easy was upgraded to a hurricane with peak winds of 105 mph (165 km/h). By that time, the hurricane had turned sharply to the east, and later began to move toward the south. As quickly as it strengthened, Easy began to weaken, and an aircraft reported winds of only 48 mph (77 km/h) on October 9. The storm headed southwest, ultimately dissipating on October 11 about 155 mi (249 km) southwest of where it formed. Easy never affected land.[4][1]

Hurricane Fox

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 20 – October 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min) 934 mbar (hPa) |

The strongest tropical cyclone of the season formed on October 20 in the Caribbean Sea off the northwest coast of Colombia,[4] believed to have been from the Intertropical Convergence Zone.[1] It moved northwestward, intensifying into a tropical storm on October 21 and a hurricane the following day. Fox subsequently turned to the north, intensifying to a major hurricane as it passed west of the Cayman Islands. Late on October 24, the cyclone struck the small island of Cayo Guano del Estes in the Archipelago de los Canarreos, south of Cienfuegos, Cuba. It struck the island with peak winds of 145 mph (230 km/h), and the island reported a minimum pressure of 934 mbar (27.59 inHg). Shortly thereafter, Fox crossed the mainland coast of Cuba west of Cienfuegos, and it weakened while crossing the island.[4][1]

Hurricane Fox crossed Cuba in a rural area dominated by sugar plantations, with heavy damage reported to 36 mills. In one town, the hurricane destroyed about 600 homes and damaged over 1,000 more.[1] Across the island, the strongest winds downed large trees and washed a large freighter ashore.[20] Heavy rainfall affected all but the extreme eastern and western end of the island, with a peak of 6.84 in (174 mm) near Havana.[21] The rains flooded low-lying areas and caused rivers to exceed their banks.[20] Throughout Cuba, Hurricane Fox killed 600 people,[22] and left behind heavy damage totaling $10 million (1952 USD, $96.3 million 2020 USD).[20] Fox was among the strongest hurricanes to strike the country.[23]

After crossing Cuba, Fox emerged into the Atlantic Ocean with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h), crossing central Andros and turning eastward though the Bahamas.[4] On New Providence, the hurricane dropped 13.27 in (337 mm) of rainfall,[21] Strong winds caused severe crop damage, leaving 30% of the tomato crop destroyed.[1] After briefly restrengthening to a major hurricane, Fox began a steady weakening trend. It turned abruptly to the north-northwest, followed by another turn to the northeast. On October 28, Fox was absorbed by a cold front west-southwest of Bermuda.[4][1]

Tropical Storm Eleven

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 26 – November 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 992 mbar (hPa) |

A cold front stalled north of the Virgin Islands on November 23, spawning an extratropical storm the next day. The system strengthened while moving northward, attaining gale force winds on November 25. It was a large system, and a ship in the vicinity reported a pressure of 994 mbar (29.4 inHg). The observation, within a warm environment and in concurrence with gale force winds, suggested that the system became a tropical storm on November 26, although the system likely was a subtropical cyclone due to the structure. Turning to the west-northwest along a dissipating cold front, the storm reached peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) on November 27. Another front in the region steered the storm to the south and east in a counterclockwise circle. Weakening slightly, the system briefly transitioned into an extratropical storm on November 30 before dissipating later that day within the front.[12]

Storm names

These names were used to name storms during the 1952 season, the third and final time storm names were taken from the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet. Names that were not used to designate tropical cyclones are marked in gray.[24]

|

|

|

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- Atlantic hurricane season

References

- Grady Norton, U.S. Weather Bureau (January 1953). "Hurricanes of the 1952 Season" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- Staff Writer (1952-06-15). "Hurricane Season Opens Today". The News and Courier. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- Robert Hunger (1952-11-14). "End of Hurricane Season". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- "Only February tropical storm hit Florida in 1952". USAToday.com. USA Today. 2008. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- Staff Writer (1952-02-04). "Cyclone Whirls Near Carolinas". United Press.

- Staff Writer (1952-02-05). "Johnny Come Lately Winds High". United Press.

- Staff Writer (1952-02-04). "Ship With 26 Is Wrecked Off Carolina As Gale From Atlantic Sweeps Up Coast". New York Times. United Press. Archived from the original on 2001-08-13. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- Staff Writer (1952-08-31). "Three Dead in U.S. Hurricane". The Age. Retrieved 2011-01-13.

- Staff Writer (1952-08-31). "Hurricane Hits Carolina Coast Areas". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-13.

- Staff Writer (1952-09-01). "Dying Hurricane Causes Big Damage". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-13.

- Chris Landsea; et al. (May 2015). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (1952) (Report). Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- Isidro D. Carino (1953). A Study of Hurricane Baker of 1952 (PDF) (Report). Defense Technical Information Center. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- Canadian Hurricane Centre (2009-11-09). "1952-Baker". Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- David M. Roth (2008-09-28). "Tropical Storm Charlie - September 21–24, 1952". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- Staff Writer (1952-09-22). "Floods, Landslides Hit Puerto Rico; 2 Missing". The Telegraph-Herald. United Press. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- Staff Writer (1952-09-24). "Floods Kill 2". Saskatoon Star-Phoenix. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- Staff Writer (1952-09-25). "Hurricane 'Charlie' Forms in Atlantic". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- Staff Writer (1952-09-28). "Hurricane Dog Degenerates Into Swirl". Sarasota Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- Staff Writer (1952-10-25). "Hurricane Skirts Florida After Lashing Cuba". Pittsburgh Press. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- David M. Roth (2010-08-17). "Hurricane Fox - October 21–29, 1952". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- "The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Roger A. Pielke Jr.; Jose Rubiera; Christopher Landsea; Mario L. Fernandez; Roberta Klein (August 2003). "Hurricane Vulnerability in Latin America and The Caribbean: Normalized Damage and Loss Potentials" (PDF). National Hazards Review. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: 108. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- Gary Padgett (2007). "History of the Naming of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, Part 1 - The Fabulous Fifties". Retrieved 2011-01-13.