1959 Atlantic hurricane season

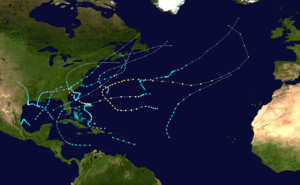

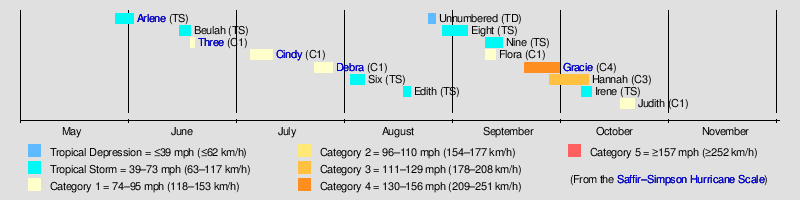

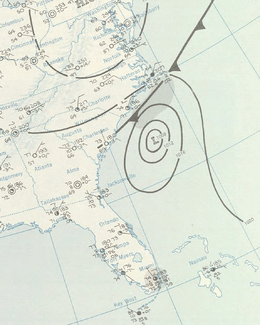

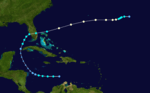

The 1959 Atlantic hurricane season had a then record-tying number of tropical cyclones – five – develop before August 1. The season was officially to begin on June 15, 1959 and last until November 15, 1959, the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin, however in actuality the season began early when Tropical Storm Arlene formed on May 28. Tropical Storm Arlene struck Louisiana and brought minor flooding to the Gulf Coast of the United States. The next storm, Beulah, formed in the western Gulf of Mexico and brought negligible impact to Mexico and Texas. Later in June, an unnamed hurricane, nicknamed the Escuminac disaster, caused minor damage in Florida and devastated coastal Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, after becoming extratropical. Hurricane Cindy brought minor impact to The Carolinas. In late July, Hurricane Debra produced flooding in the state of Texas. Tropical Storm Edith in August and Hurricane Flora in September caused negligible impact on land.

| 1959 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 28, 1959 |

| Last system dissipated | October 21, 1959 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Gracie |

| • Maximum winds | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 951 mbar (hPa; 28.08 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 15 |

| Total storms | 14 |

| Hurricanes | 7 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 58 direct, 6 indirect |

| Total damage | At least $24 million (1959 USD) |

| Related articles | |

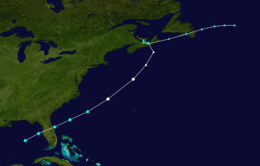

The most significant storm of the season was Hurricane Gracie, which peaked as a 140 mph (220 km/h) Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. After weakening slightly, Gracie made landfall as a 130 mph (215 km/h) Category 4 hurricane in South Carolina on September 29. It brought strong winds, rough seas, heavy rainfall, and tornadoes to the state, as well as North Carolina and Virginia. Overall, Gracie caused 22 fatalities and $14 million in damage. Following Hurricane Gracie was Hurricane Hannah, a long-lived storm that did not cause any known impact on land. The last two tropical cyclones, Tropical Storm Irene and Hurricane Judith, both caused minor coastal and inland flooding in Florida. The storms of the 1959 Atlantic hurricane season were collectively attributed to $24 million (1959 USD) and 64 fatalities.

Season summary

The 1959 Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 15, 1959, and it ended on November 15, 1959.[1] Eleven tropical depressions developed during the season. All eleven of the depressions attained tropical storm status,[2] which was slightly above the 1950–2000 average of 9.6 named storms.[3] Of the eleven systems, seven of them attained hurricane status,[2] which was also slightly above the average of 5.9.[3] Furthermore, two storms reached major hurricane status – Category 3 or greater on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale.[4] Five tropical storms and three hurricanes made landfall during the season and caused 64 fatalities and about $24 million (1959 USD) in damage.[2]

Season activity began with the development of Tropical Storm Arlene on May 28. In the month of June, Tropical Storm Beulah and an unnamed hurricane formed, the latter becoming a hurricane on June 19. Another pair of hurricanes, Cindy and Debra, formed in the month of July.[2] Collectively, the five tropical cyclones that formed in May, June, and July made the 1959 season the one of the most active seasons before August 1, tied with 1887, 1933, 1936, 1966, 1995, 1997, and 2020. The record was later surpassed in 2005 when seven tropical cyclones formed before August 1.[5] However, tropical cyclogenesis slowed down in August, with only Tropical Storm Edith forming during the month. Next, three tropical cyclones formed in September – Flora, Gracie, and Hannah – all of which attained hurricane status. Furthermore, in October, Tropical Storm Irene and Hurricane Judith, the 1959 season's final storm, developed. The latter storm dissipated on October 21,[2] almost a month before the official end of the season on November 15.[1]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 77,[6] which is slightly below the 1950–2000 average of 94.7.[3] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 34 knots (39 mph, 63 km/h) or tropical storm strength.[7]

Systems

Tropical Storm Arlene

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 28 – June 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 993 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into the first tropical depression of the season on May 28, while located in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico.[2][4] The depression strengthened and, early on the following day, was upgraded to Tropical Storm Arlene.[2] The storm slowly intensified and reached its peak intensity of 65 mph (100 km/h) on May 29.[4] Rapid weakening took place as the storm approached land. By late on May 30, Arlene made landfall near Lafayette, Louisiana with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h).[2][4] Early on the following day the storm weakened to a tropical depression while barely inland.[4] The system eventually curved east-northeastward and meandered across the Southern United States until dissipating over South Carolina on June 2.[4]

In Louisiana, a state maximum rainfall of 13.13 in (334 mm) fell in Houma.[2] As a result, a few towns along the coast reported downed trees and electrical lines from high winds, which caused scattered power outages.[8] In New Orleans, several roads were shut down due to inundation.[9] Additionally, at least 100 homes within the city were flooded. In Baton Rouge, dozens of people were evacuated from a flooded home via ambulance and wagon to safer areas.[10] Overall, damage was light, reaching $500,000. One death was related to Arlene; a man drowned in rough surf off the coast of Galveston, Texas.[2] After storm dissipated over the Southeastern United States, the extratropical remnants of Arlene brought moderate rainfall to parts of the Mid-Atlantic States and New England.[11]

Tropical Storm Beulah

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 15 – June 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 985 mbar (hPa) |

A cold front became stationary as it began to move across the Gulf of Mexico on June 13. After the SS Hondo reported winds of 60 mph (95 km/h),[2] it is estimated that a tropical depression developed at 1800 UTC on June 15, while located in the southwestern Gulf of Mexico. By June 16, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Beulah. Further deepening occurred and the storm peaked with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) on June 17.[4] As Beulah neared the Gulf Coast of Mexico, a building ridge of high pressure forced the storm southward. It then began to encounter stronger upper level winds and weakened to a tropical depression on June 18.[2][4] Shortly thereafter, the storm dissipated about 20 miles (32 km) northeast of Tuxpan, Veracruz.[4] Tides of 2 to 3 feet (0.61 to 0.91 m) above normal occurred along the Texas coast, though no impact was reported in Mexico.[12]

Hurricane Three

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 18 – June 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 974 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression while situated in the central Gulf of Mexico on June 18. It headed rapidly northeastward and made landfall near the Tampa Bay Area of Florida later that day.[2] The storm dropped moderately heavy rainfall in Florida, which caused damage to crops. An F3 tornado near Miami and high tides on the west coast of the state also resulted in damage.[13] Losses in Florida were around $1.7 million.[2] Shortly thereafter, in entered the Atlantic Ocean and strengthened into a tropical storm later on June 18. By the following day, it had strengthened into a hurricane; the storm simultaneously peaked with maximum sustained winds of 85 mph (135 km/h).[4]

The storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on June 19. The remnants struck Atlantic Canada, once in Nova Scotia and again in Newfoundland before dissipating on June 21.[4] After becoming extratropical, the storm caused significant effects in Atlantic Canada. About 45 boats were in the Northumberland Strait between New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, and they did not have radio to receive warning of the approaching storm. Rough seas of up to 49 ft (15 m) in height damaged or destroyed many boats. At least 22 fishing boats capsized over water with their crew, causing 35 deaths. High winds also disrupted communications in some areas, and several houses were damaged, with losses reaching about $781,000.[14] The New Brunswick Fishermen's Disaster Fund was created to assist victims. The fund raised $400,000 in a few months from donations from throughout Canada, as well as Pope John XXIII and Queen Elizabeth II, the latter of whom was on a tour of the country at the time.[15]

Hurricane Cindy

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 4 – July 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 995 mbar (hPa) |

A low-pressure area associated with a cold front developed into a tropical depression on July 5, while located east of Florida.[2][4] Tracking north-northeastward, it strengthened into Tropical Storm Cindy by the next day.[4] Cindy turned westward because of a high-pressure area positioned to its north,[2] and further intensified into a hurricane offshore the Carolinas on July 8.[4] Cindy made landfall near McClellanville, South Carolina early on July 9,[4][2] and re-curved to the northeast along the Fall Line as a tropical depression. It re-emerged into the Atlantic on July 10 and quickly restrengthened into a tropical storm.[4] On July 11, Cindy passed over Cape Cod, while several other weather systems helped the storm maintain its intensity.[2] Cindy transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on July 12 while approaching Atlantic Canada.[4]

Overall structural damage from Cindy was minimal. One driver was killed in Georgetown, South Carolina after colliding with a fallen tree,[16] and five deaths were caused by poor road conditions wrought by the storm in New England.[17] Many areas experienced heavy rains, and several thousand people evacuated. Damage was mainly confined to broken tree limbs, shattered windows and power outages.[18] Cindy brought a total of eleven tornadoes with it, of which two caused minor damage in North Carolina.[19] The heaviest rainfall occurred in northern South Carolina, where rainfall amounted to 9.79 inches (249 mm).[20] Tides ranged from 1 to 4 feet (0.30 to 1.22 m) above normal along the coast. As drought-like conditions were present in The Carolinas at the time, the rain that fell in the area was beneficial.[21] After becoming extratropical over Atlantic Canada, the cyclone produced heavy rains and strong winds that sunk one ship.[22] Damage caused by Cindy was estimated at $75,000.[2]

Hurricane Debra

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 22 – July 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 980 mbar (hPa) |

On July 23, interaction of a cold-core low and a tropical wave spawned a tropical depression located south of Louisiana.[4][2] The depression meandered westward while steadily intensifying, becoming a Tropical Storm on July 24. A turn towards the northwest became evident as it attained Category 1 hurricane status on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale on the following day.[4] Strength was maintained as the hurricane curved northward at a slow forward speed, and it approached the coast of Texas as a minimal hurricane. Debra made landfall between Freeport and Galveston, Texas early on July 25.[2] Debra rapidly weakened into a tropical storm and later a depression as it moved inland, and it dissipated on July 28.[4] The remnant moisture later sparked upper-level thunderstorms in late July and early August.[2]

Torrential rains were produced in southeastern Texas, peaking at 15.89 inches (404 mm) in Orange.[23] This led to widespread flooding on highways, including portions of Farm Road 518, Highway 6, Highway 146, and U.S. Route 75.[24] Sea vessels took the brunt of the storm, with many becoming stranded or damaged. Air, rail, and road transportation were significantly interrupted or even shut down. High winds from the storm caused expansive damage to buildings, windows, signs, and roofs.[25] The hurricane resulted in 11 injuries but no human deaths,[26] although approximately 90 cattle drowned.[25] Damage in Brazoria, Galveston, and Harris counties surmounted $6.685 million. Additionally, impact in other areas increased the total losses to $7 million.[2]

Tropical Storm Six

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 2 – August 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 999 mbar (hPa) |

A weakening cold front spawned a tropical depression on August 2 near the Outer Banks of North Carolina. The structure was broad, possibly akin to a subtropical cyclone. The storm quickly intensified based on ship reports, possibly to hurricane intensity, although the maximum sustained winds were estimated at 70 mph (110 km/h). An approaching frontal boundary caused the storm to accelerate northeastward, while also bringing drier air into the windfield, causing weakening. On August 4, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone, and for two days drifted toward Atlantic Canada before dissipating. The storm was added to the Atlantic hurricane database in 2016.[27]

Tropical Storm Edith

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 18 – August 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave was tracked east of the Lesser Antilles in mid-August. At 1530 UTC on August 17, a reconnaissance aircraft reported a weak center and winds of 35 mph (55 km/h).[2] Less than three hours later, a tropical depression developed while located east of the Windward Islands. The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Edith early on August 18.[4] The storm moved west-northwestward at a relatively quick pace, striking Dominica with winds peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) on August 18.[27][4][2] By 1800 UTC on August 18, Edith peaked with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h). It curved westward and accelerated on August 19. Edith weakened to a tropical depression at 1200 UTC, hours before dissipating near the southern tip of Dominican Republic.[4] There was "considerable doubt" if a circulation ever existed.[2] Squally weather and gusty winds were reported in some areas, including Guadeloupe, the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, and Hispaniola.[28]

Tropical Storm Eight

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 28 – September 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 996 mbar (hPa) |

A dissipating cold front spawned a low pressure over the central Atlantic Ocean on August 26. Moving slowly northward, the system organized into a tropical storm on August 28, and a day later, an approaching cold front turned the storm to the east-northeast. Based on ship observations, it is estimated that the storm reached peak winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) on August 31. By September 3, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone as it interacted with the cold front, located halfway between Newfoundland and the Azores. A day later, the storm was absorbed by a larger extratropical storm southwest of Iceland. The storm was added to the Atlantic hurricane database in 2016.[27]

Tropical Storm Nine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 9 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) |

On September 6, a broad low pressure area developed between the Bahamas and Bermuda. The system moved northward, organizing into a tropical storm on September 9. The system had a large wind field, and was likely a subtropical cyclone. Moving northwestward at first, the storm turned to the northeast ahead of a cold front, with sustained winds of around 45 mph (75 km/h). Nantucket island in Massachusetts reported sustained winds of 39 mph (63 km/h) during the storm's passage. On September 11, the storm interacted with the cold front, becoming an extratropical storm, which lasted until September 14. The storm was added to the Atlantic hurricane database in 2016.[27]

Hurricane Flora

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 9 – September 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 994 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave passed through the islands of Cape Verde on September 6 and tracked westward at about 19 mph (31 km/h).[2] Early on September 9, a tropical depression developed while located about midway between Cape Verde and the Lesser Antilles. The depression moved northeastward and by September 10 it strengthened into Tropical Storm Flora.[4] A reconnaissance aircraft flight into the storm on September 11 recorded winds of 75 mph (120 km/h); thus, Flora became a hurricane.[2] Around the time, the storm attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of the same velocity and a minimum barometric pressure of 994 mbar (29.4 inHg). Flora then accelerated northeastward toward the Azores.[4] During another reconnaissance flight on September 12, no evidence of a tropical cyclone was reported.[2] Thus, Flora became extratropical at 1200 UTC that day.[4]

Hurricane Gracie

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 20 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min) 951 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave spawned a tropical depression north of Hispaniola on September 20.[2][4] The depression remained offshore the island and moved west-northwestward. By September 22, it curved northeastward and became Tropical Storm Gracie.[4] The storm then moved through The Bahamas, producing 8.4 inches (210 mm) on Mayaguana.[2] Later on September 22 Gracie intensified into a hurricane. It deepened further to a Category 2, on September 23, before weakening later that day. Gracie then meandered slowly and erratically while northeast of The Bahamas, before curving northwestward on September 27. It became a Category 2 hurricane again by September 28. During the next 24 hours, Gracie deepened significantly and peaked as a 140 mph (220 km/h) Category 4 hurricane.[4] However, it weakened slightly to a 130 mph (215 km/h) Category 4 hurricane before making landfall on Edisto Island, South Carolina at 1625 UTC on September 29.[29][4][30] Gracie was the one of the strongest tropical cyclones to strike South Carolina until Hurricane Hugo in 1989.[31] It rapidly weakened inland, becoming extratropical on September 30.[4]

Along the coast of South Carolina, the highest tide recorded was 9.7 feet (3.0 m) above mean low water at Charleston Harbor. On Folly Beach, all waterfront houses sustained some damage, while roads on the east side of the island were washed away. Gracie brought wind gusts as high as 138 mph (222 km/h) to the Beaufort area. Inland, 100 mph (155 km/h) winds lashed Walterboro. As much as 75% of Charleston County was left without electricity. Farther north, a F1 tornado damaged homes in Garden City. Throughout the South Carolina Lowcountry, 48 homes were destroyed, 349 homes suffered major damage, and 4,115 homes suffered minor damage.[31] The remnants dropped rainfall and spawned tornadoes in several other states as it headed northeastward across the Mid-Atlantic and New England regions. In Virginia, three F3 tornadoes in Albemarle, Greene, and Fluvanna Counties collectively caused 12 fatalities and 13 injuries.[32] Precipitation from the storm peaked at 13.2 inches (340 mm) in Big Meadows.[23] Overall, Gracie caused 22 deaths and $14 million in damage.[2]

Hurricane Hannah

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 27 – October 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min) 959 mbar (hPa) |

After ships reported a low-level circulation,[2] it was estimated that a tropical depression developed at 26.8°N, 49.9°W on September 27. Early on the following day, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Hannah.[4] Reconnaissance aircraft flew into the storm late on September 28 and indicated that Hannah intensified into a Category 1 hurricane.[2][4] Hannah moved generally westward at about 16 mph (26 km/h).[2] By September 30, the storm became a Category 2 hurricane, and it curved northwestward later that day. Hannah deepened to a Category 3 hurricane on October 1, hours before the storm reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 120 mph (195 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 959 mbar (28.3 inHg). The storm maintained this intensity for about 48 hours and curved northeastward on October 2.[4]

Hannah began to a weaken late on October 3. By the following day, the storm fell to Category 2 hurricane intensity.[4] It accelerated eastward or east-southeastward across the central Atlantic, starting on October 4.[2] Hannah re-strengthened slightly to a 110 mph (175 km/h) Category 2 hurricane on October 5, but then slowly began weakening again.[4] The final advisory on the storm was issued early on October 7, while it was centered about 200 miles (320 km) south-southwest of the Azores,[2] however Hannah remained a tropical cyclone and crossed through the Azores later that day.[4] No impact was reported in the islands.[2] It weakened to a Category 1 hurricane early on October 8, and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over the far northeastern Atlantic several hours later.[4]

Tropical Storm Irene

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 6 – October 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

In early October, a cold front drifted through Texas and entered the Gulf of Mexico. On October 5 the front dissipated while a related trough persisted. Upper-level air temperatures were generally warm, and a minimal anticyclone was situated over the Gulf.[2] At this time, a Colorado low drew polar air into the Mississippi Valley, suggesting extratropical characteristics of the developing system.[33] A tropical depression formed on October 6;[4] it meandered in a north-northeasterly direction for the next two days.[2] The storm intensified into Tropical Storm Irene around 1800 UTC on October 7.[4] Around this time, a Hurricane Hunters flight indicated that the circulation was indistinct, although it was gradually evolving.[34] On October 8, Irene made landfall near Pensacola, Florida as a well-organized tropical storm. The storm rapidly weakened to a tropical depression, before dissipating early on October 9.[2][4]

The highest tides, 4.4 ft (1.3 m) above normal, were reported at Cedar Key, Florida, while the strongest gust recorded, 55 mph (89 km/h), was measured at Pensacola International Airport.[2] Heavy rainfall from Irene spread across much of the Southern United States, peaking at 10.96 inches (278 mm) in Neels Gap, Georgia.[20][35] In Florida, flooding from rainfall associated with Irene caused damage around the Lake Okeechobee area.[33] Losses in Florida was limited to uncollected crops, mainly peanuts and corn, that were in bales in the process of being dried.[36] Several floods were flooded along the coast at Shalimar near Fort Walton Beach. The winds downed trees and a telephone pole, causing a short power outage in Ocean City.[37] Red tides were ongoing in western Florida; winds from the storm's precursor blew thousands of dead fish ashore. Local residents complained that the odor from the rotting fish were unbearable.[38]

Hurricane Judith

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 14 – October 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 988 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into Tropical Storm Judith on October 17, near the Yucatán Channel.[2][4] It strengthened quickly, and by early on October 18 the storm was upgraded to a Category 1 hurricane. However six hours later Judith had weakened back to a tropical storm.[4] Around 1800 UTC on October 18 the storm made landfall near Boca Grande, Florida, with winds of 50 mph (85 km/h).[4][2] After emerging into the Atlantic Ocean on the following day, Judith began re-strengthening while heading east-northeastward, reaching hurricane status several hours later. It peaked with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) early on October 20, before weakening back to a tropical storm again on October 21.[4] Judith weakened further, before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone later that day.[2]

Impact from Judith was generally minor and limited mostly to Southwest Florida. Wind gusts up to 56 mph (90 km/h) toppled several trees on Sanibel Island and a few power poles; a man was injured when his car struck a fallen pole. Rough seas caused erosion on Captiva Island and in Fort Myers, while also inundating several roads in the area. A combination of locally heavy rainfall and tides caused minor flooding in low-lying areas.[39] Precipitation from the storm peaked at 7.90 inches (201 mm) in Miles City.[23] The Imperial River overflowed near Bonita Springs, flooding pasture lands and washing out crops, most of which were recently planted. A portion of U.S. Route 41 was inundated by up to 3 feet (0.91 m) of water in Bonita Springs.[39]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms (tropical storms and hurricanes) that formed in the North Atlantic in 1959. With the exception of Irene, all names in this list were used for the first time in 1959.[40] The names Gracie, Hannah and Judith were later removed from the list and were replaced with Ginny, Helena and Janice in 1963.[41][42]

|

|

|

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- Atlantic hurricane season

- 1959 Pacific hurricane season

References

- "Hurricane Season Makes Official Arrival At Midnight". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. June 15, 1959. p. 9. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- Dunn, Gordon E. (1959). "The Hurricane Season of 1959". Monthly Weather Review. 87 (12): 441–450. Bibcode:1959MWRv...87..441D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493-87.12.441. S2CID 124901540.

- Philip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (December 8, 2006). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2007 (Report). Colorado State University. Archived from the original on December 18, 2006. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Cory Pesaturo (May 2006). Cory Pesaturo's 2005 Atlantic Hurricane Season Records List (PDF) (Report). Weather Underground. p. 11. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- Hurricane Research Division (March 2011). Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- David Levinson (August 20, 2008). "2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- "Storm Arlene, Losing Power, Hits La. Coast". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. May 31, 1959. p. 1. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- "Storm Arlene Blowing Itself Out In Center Of Mississippi Today". Ocala Star-Banner. Associated Press. June 1, 1959. p. 10. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- "Storm Arlene Dumps Heavy Rain on La". Aiken Standard and Review. United Press International. June 1, 1959. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- David M. Roth (2010). Tropical Storm Arlene – May 30 – June 3, 1959 (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- Preliminary Report on Tropical Storm Beulah June 15–18, 1959. United States Weather Bureau (Report). National Hurricane Center. 1959. p. 1. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. United States Department of Commerce. 1 (6). June 1959. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- 1959-NN-1 (Report). Environment Canada. September 14, 2010. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

- Nicole Lang. The Escuminac Disaster (PDF) (Report). Government of New Brunswick. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- McHugh, Robert (July 9, 1959). "Weakened Storm Crawling North". The Rock Hill Herald. Associated Press. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- "New England Hit By A Soggy Cindy". The Miami News. United Press International. July 12, 1959. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- "Cindy Loses Punch". Sarasota Journal. United Press International. July 9, 1959. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- John S. Smithdate=July 1965 (1965). "The Hurricane-Tornado" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 93 (7): 458. Bibcode:1965MWRv...93..453S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1965)093<0453:THT>2.3.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0493.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southeastern United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- Preliminary Report on Hurricane Cindy, July 7–11, 1959 (GIF). Weather Bureau (Report). National Hurricane Center. July 1959. p. 2. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- 1959-Cindy (Report). Environment Canada. November 11, 2009. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- Roth, David M. (October 18, 2017). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Ernest Carson; James G. Taylor (1959). Tropical Hurricane Debra, July 24–25, 1959 (Report). United States Weather Bureau. p. 1. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- Ernest Carson; James G. Taylor (1959). Tropical Hurricane Debra, July 24–25, 1959 (Report). United States Weather Bureau. p. 2. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- "Hurricane Debra Hits; Hundreds Flee Storm". The Telegraph-Herald. Associated Press. July 26, 1959. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- Sandy Delgado; Chris Landsea (July 2016). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (1959) (PDF) (Report). Hurricane Research Division. p. 1. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- Report on Tropical Storm Edith August 17–19, 1959 (Report). National Hurricane Center. August 26, 1959. p. 2. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- "Reanalysis of 1956 to 1960 Atlantic hurricane seasons completed" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- Cummings (September 29, 1959). Local Statement By Weather Bureau Charleston, South Carolina, Hurricane Gracie. Weather Bureau Office Charleston, South Carolina (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 30. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- 50th Anniversary of Hurricane Gracie (PDF). National Weather Service Charleston, South Carolina (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2009. pp. 1, 7, 9. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- Virginia's Weather History (Report). Virginia Department of Emergency Management. 2009. Archived from the original on July 17, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- Robert H. Gelhard (October 1959). "The Weather and Circulation of October 1959" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 87 (10): 392, 394. Bibcode:1959MWRv...87..388G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1959)087<0388:TWACOO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0493. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- Tropical Storm Irene – October 6–8, 1959. United States Department of Commerce (Report). Washington, D.C.: Weather Bureau. October 1959. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- David M. Roth (2012). Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the Gulf Coast (Report). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- Butson, Keith (October 20, 1959). Office Memorandum – Tropical Storm Irene. State Climatologist's Office (Report). Gainesville, Florida: Weather Bureau. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- Staff writer (October 8, 1959). "Florida Resort Area Is Lashed By Storm Irene". Meriden Journal. Pensacola, Florida. Associated Press. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- Staff writer (October 8, 1959). "Beaches May Get More Dead Fish". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. St. Petersburg, Florida. Associated Press. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- Tropical Storm Judith, October 17–18, 1959, Lee County, Florida. Weather Bureau Office Fort Myers, Florida (Report). National Hurricane Center. October 23, 1959. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- "Names Ready". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. May 29, 1959. p. 24. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- Gary Padgett; Jack Beven; James Free; Sandy Delgado (May 23, 2012). Subject: B3) What storm names have been retired? (Report). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names (Report). National Hurricane Center. April 13, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2013.