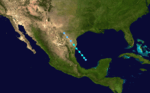

1958 Atlantic hurricane season

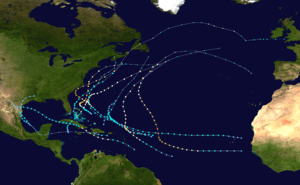

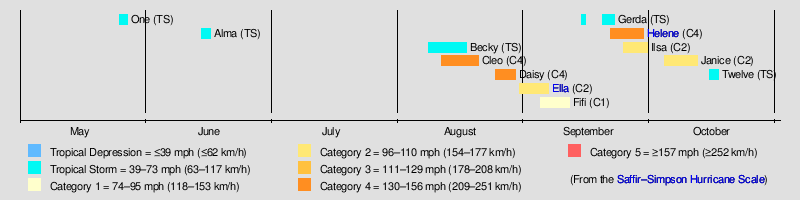

The 1958 Atlantic hurricane season included every tropical cyclone either affecting or threatening land. There were ten named storms as well as one pre-season tropical depression. Seven of the storms became hurricanes, including five that were major hurricanes, or the equivalent of a Category 3 on the Saffir-Simpson scale. The strongest storm was Hurricane Helene, which became a strong Category 4 hurricane with 150 mph (240 km/h) winds and a barometric pressure of 930 mbar (27.46 inHg) while just offshore the southeastern United States.

| 1958 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 25, 1958 |

| Last system dissipated | October 17, 1958 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Helene |

| • Maximum winds | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 930 mbar (hPa; 27.46 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 12 |

| Total storms | 12 |

| Hurricanes | 7 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 52 overall |

| Total damage | $11.65 million (1958 USD) |

| Related articles | |

In May, a subtropical depression formed in the Caribbean and dropped heavy rainfall near Miami, Florida. The first named storm of the season was Alma, which killed three people and caused flooding in Texas. Hurricane Daisy in August was a major hurricane that paralleled the eastern coast of the United States, although due to its small size it did not cause much damage. Hurricane Ella affected much of the northern Caribbean and Texas, most significantly the Dominican Republic where 30 people died. Ella also killed six people in Cuba, where it made landfall as a major hurricane. A few weeks later, Tropical Storm Gerda also struck the Dominican Republic and killed three people. The costliest storm of the season was Helene, which caused $11.2 million in damage (1958 USD), mostly in North Carolina. Although it passed within 10 mi (16 km) of the state, its effects were mostly limited to the coast, and the hurricane killed one person. The last storm of the season, Janice, killed eight people in Jamaica when its precursor dropped 20 in (510 mm) of rainfall, and one person was killed in the Bahamas.

Season summary

The ten tropical storms during the season is comparable to the 20 year average of ten. In contrast to the previous season when most storms were in the Gulf of Mexico, most storms in 1958 occurred over the western Atlantic Ocean. The first storm, Alma, formed in the middle of June. Subsequently, a trough persisted along the eastern United States, which suppressed tropical cyclone formation. Conditions remained unfavorable in July due to a large ridge suppressing the westerlies. In August, a persistent trough caused three storms – Becky, Cleo, and Daisy – to recurve and remain over the ocean. Most storms formed from the middle of August through the middle of October, when polar air reached as far south as Florida due to a shift in the ridge.[1]

Before the season started, the United States Weather Bureau office in Miami began setting up a teleprinter to distribute hourly advisories to newspapers and the American Red Cross. The hurricane season officially began on June 15, and lasted until November 15.[2] When the season started, the Lakeland Frost Warning Service sent four employees to assist the Miami Weather Bureau. The Hurricane Hunters flew daily to investigate potential storms in the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. In addition, there was a set of radars from Texas to Maine to track storms. Beginning in 1958, the Weather Bureau predicted the change in tide due to a storm with the assistance of a tide specialist.[3] During the season, a reporter – daughter of Weather Bureau director Gordon Dunn – flew into Hurricane Daisy, becoming the first woman to fly into a hurricane.[4] Utilizing radars along the East Coast of the United States, the Weather Bureau tracked both Hurricanes Daisy and Helene for 575 mi (925 km), which was the first such occurrence of that feat.[5]

The season's activity was reflected with a cumulative accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 121.[6] ACE, broadly speaking, is a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high values. ACE is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 34 knots (39 mph, 63 km/h) or tropical storm strength.[7]

Systems

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 25 – May 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 999 mbar (hPa) |

A small circulation crossed Panama from the Pacific Ocean on May 17, and by the following day it was a developing depression near San Andrés in the western Caribbean. The system gradually organized over warm waters while moving to the northwest, developing a well-defined low pressure area by May 23 as it approached western Cuba. Later that day, the depression crossed the western portion of the island before turning to the northeast. On May 24, the system passed southeast of Florida, dropping heavy rainfall that peaked at 12.07 in (307 mm) in Homestead.[8] May 1958 was the second wettest May since 1911, of which half of the precipitation fell during the depression.[9] Several other locations in the Miami area reported record or near-record rainfall for the month. The high rainfall disrupted planting of vegetables, and there was some crop damage.[8] Flooding entered homes and businesses, forcing some evacuations. About 2,900 people lost telephone service, and there was a brief water outage on Key Biscayne. There were also hundreds of vehicle accidents related to the storm.[10]

After affecting Florida, the depression continued to the northeast, and although it had a warm core, it was not able to develop significantly due to lack of temperature instability, as well as another low developing southwest of the circulation. The depression was briefly forecast to strike North Carolina, but instead an eastward moving ridge kept it offshore. In Hatteras, North Carolina, the depression dropped 3 in (76 mm) of rainfall. The influx of cold air transitioned the depression to an extratropical cyclone on May 28. An approaching cold front absorbed the depression and produced heavy rainfall in eastern Canada.[8]

Tropical Storm Alma

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 14 – June 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 997 mbar (hPa) |

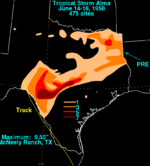

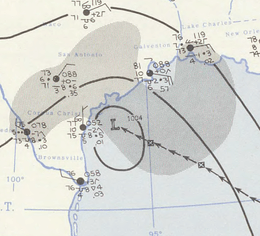

A tropical wave was first observed in the central Caribbean Sea on June 9. By the following day, there was evidence of a weak closed circulation off the south coast of Jamaica. Moving generally westward, on June 12 it crossed the Yucatán Peninsula, and the system emerged into the Bay of Campeche the next day. On June 14, a tropical depression formed about halfway between the Yucatán Peninsula and Tamaulipas. Within six hours, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Alma about 150 mi (240 km) east of Tampico. Later that day, a ship reported a pressure of 997 mbar (29.4 inHg) and high seas, and early on June 15 a United States Coast Guard plane measured winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) near the northeast Mexican coast.[1] That day, Alma made landfall about 70 mi (110 km) south of Brownsville, Texas in northeastern Mexico.[11] The storm moved ashore in northeastern Tamaulipas early on June 15 before crossing into southern Texas. After weakening to a tropical depression, Alma straddled the Rio Grande before dissipating in western Texas late on June 16.[12]

The United States Coast Guard recommended people to evacuate in beach areas near Brownsville, Texas. As it moved ashore, Alma produced a high tide of 2.9 ft (0.88 m) along Padre Island, and one person drowned near Galveston due to heavy surf. The highest wind gust was 45 mph (72 km/h) at Port Isabel,[11] causing minor damage. However, Alma dropped heavy rainfall further inland, reaching about 20 in (510 mm) near Medina. The rains caused floods that resulted in heavy damage to property and crops.[1] Some rivers and streams rose above their banks due to floods,[13] creating torrents of up to 15 ft (4.6 m) in some arroyos.[14] The floods covered highways and forced about 100 people to evacuate near Sabinal. The rains also knocked out telephone lines in Uvalde County, and temporarily trapped hundreds of scouts. One person drowned along the Concho River,[15] and three people overall died due to the system.[14]

Tropical Storm Becky

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 8 – August 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 982 mbar (hPa) |

Based on reports from the Cape Verde islands offshore Africa, it is estimated a tropical depression developed on August 8. It moved westward due to the subtropical ridge to its north, a motion the depression would continue for much of its duration. Nearby ship reports indicated gradual strengthening,[1] and the depression became a tropical storm on August 11.[12] At 0400 UTC on August 12, the San Juan Weather Bureau office initiated advisories on Tropical Storm Becky about halfway between the Lesser Antilles and Cape Verde.[16] That day, the Hurricane Hunters flew into the storm, reporting a pressure of 1,006 mbar (29.7 inHg) and flight level winds of 70 mph (110 km/h);[1] its peak surface winds were estimated at 60 mph (95 km/h).[12] Also on August 12, a storm warning was issued for the northern Leeward Islands, and a storm watch was issued for the United States Virgin Islands and northern Puerto Rico.[17]

After peaking in intensity, Becky continued quickly to the west-northwest, and its fast motion may have prevented further strengthening. On August 14, a flight reported hurricane-force wind gusts in rainbands 210 mi (340 km) east-northeast of the center. The next day, the circulation became poorly defined, and by August 16, Becky had become extratropical after it merged with an approaching cold front.[1] The storm turned to the north and northeast, dissipating later on August 17.[12] As Becky was transitioning into an extratropical storm, it produced high waves along the southeastern coast of the United States.[18]

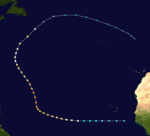

Hurricane Cleo

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 11 – August 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min) 947 mbar (hPa) |

A well-developed tropical wave spawned a tropical storm on August 11 to the south of Cape Verde. It moved westward, and ships in the area indicated that it had a large circulation. The Hurricane Hunters flew into the system and observed a well-developed hurricane with winds of 146 mph (235 km/h), which were the highest measured winds.[1] As a result, the San Juan Weather Bureau Office initiated advisories on Hurricane Cleo and issued a hurricane watch for the Lesser Antilles.[19] Subsequent analysis determined that Cleo became a hurricane on August 13.[12] A weak trough near 50° W allowed the hurricane to turn to the north, and Cleo continued to intensify, based on improved definition of the eye on radar imagery. A flight into the storm late on August 16 indicated a pressure of 947 mbar (28.0 inHg) with winds of 140 mph (230 km/h) early on August 16. Originally winds were thought to be higher in Cleo, at 160 mph (260 km/h), which would make it a Category 5 hurricane, but reanalysis later on determined it to be weaker.

After maintaining peak winds for about six hours, Cleo began weakening. It turned more to the northwest due to a strengthening ridge to the northeast and the hurricane's outflow weakening the trough. An approaching cold front turned Cleo to the northeast on August 18 and caused it to accelerate. That day, it passed about 450 mi (720 km) east of Bermuda. On August 20, the hurricane became extratropical to the southeast of Newfoundland.[1] In St. John's, the storm dropped about 2 in (51 mm) of rainfall.[20] The remnants of Cleo turned to the east and east-southeast, dissipating on August 22 between the Azores and mainland Portugal.[12]

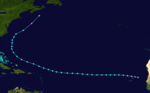

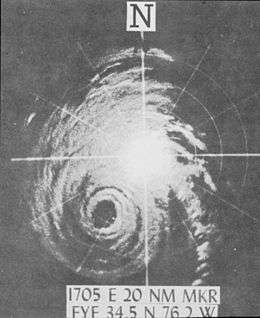

Hurricane Daisy

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 24 – August 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min) 948 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved through the Lesser Antilles on August 20 and gradually spread north.[1] On August 24, a nearby ship reported a low pressure area and strong winds, indicating the formation of a small tropical cyclone near the Bahamas.[21] After a Hurricane Hunters flight indicated winds of 55 mph (89 km/h), the Weather Bureau initiated advisories on Tropical Storm Daisy early on August 25 to the north of the Bahamas.[1] That day it became a hurricane, and initially it moved slowly to the northwest due to a ridge to the northeast. On August 26, a trough turned Daisy to the northeast, and the hurricane continued to intensify due to an anticyclone aloft.[1] By early August 28, the hurricane reached peak winds of 130 mph (215 km/h),[21] and a minimum pressure of 948 mbar (28.0 inHg) while offshore South Carolina.[22] Daisy accelerated to the north, passing about 75 mi (121 km) east of Hatteras, North Carolina; there, gusts peaked at 36 mph (58 km/h) due to the storm's small size.[1]

For much of its duration, Hurricane Daisy was visible from radar along the eastern United States, which assisted in tracking the storm. Passing east of Hatteras, Daisy dropped moderate rainfall, peaking at 5.92 in (150 mm) near Morehead City, North Carolina,[23] before turning to the northeast on August 29. The Weather Bureau issued a hurricane warning from Block Island to Provincetown, Massachusetts due to the projected path near New England. Later on August 29, Daisy passed about 70 mi (110 km) southeast of Nantucket. Nearby Block Island reported peak gusts of 45 mph (72 km/h), and a Texas Tower 120 mi (190 km) east of Cape Cod reported gusts to 87 mph (140 km/h).[1] The storm also produced high tides and light rainfall, and forced 600 people to evacuate Nantucket.[24] Due to its small size, there was no major damage in the United States.[1] After affecting Nantucket, Daisy weakened and became extratropical by early on August 30. The remnants turned to the east, passing south of Nova Scotia before dissipating on August 31.[12] In Canada, the storm damaged a boat in the Bay of Fundy that drifted for two days until reaching Saint John, New Brunswick.[25]

Hurricane Ella

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 30 – September 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) 983 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave spawned a tropical depression near the Lesser Antilles on August 30, which quickly became Tropical Storm Ella. It quickly intensified in the eastern Caribbean into a hurricane by August 31 while passing south of Puerto Rico; there, the outer rainbands caused some flooding that caused minor damage. On September 1, Ella strengthened to winds of 110 mph (180 km/h), as measured by the Hurricane Hunters. At that intensity, the hurricane passed just south of the Dominican Republic before making landfall in southwestern Haiti. In the Dominican Republic, heavy rainfall and floods caused $100,000 in damage, mostly in the country's southwestern portion. Heavy rainfall caused widespread flooding in southwestern Haiti, and thousands of people became homeless after their houses were damaged. Near Les Cayes, 30 people were killed due to flash flooding.[1]

After affecting Haiti, Ella weakened to a Category 1 hurricane before moving ashore in southeastern Cuba early on September 2. While traversing the island, Ella weakened to a tropical storm and was unable to restrengthen.[1] Near Santiago de Cuba, the Bayamo River washed away 25 houses and killed five people. One other person died in the country due to the hurricane.[26] After Ella reached the Gulf of Mexico on September 3, its structure was disrupted, and it remained a tropical storm as it continued to the west-northwest. Its outer rainbands produced gusts of 75 mph (121 km/h) in Grand Isle, Louisiana. Ella struck Texas on September 6 and dissipated soon thereafter. At its final landfall, the storm produced 13.6 in (350 mm) of rainfall in Galveston, Texas, and in the city, one person died after falling overboard a boat.[1]

Hurricane Fifi

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 4 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

A ship on September 4 indicated a tropical depression developed from a tropical wave to the east of the Lesser Antilles. The system initially had two circulations that consolidated into one by September 5. That day, Hurricane Hunters observed 55 mph (89 km/h) winds, which prompted the Weather Bureau to upgrade it to Tropical Storm Fifi.[1] Due to the storm's fast track to the northwest, a gale warning and hurricane watch were issued for the Leeward and northern Windward Islands.[27] On September 6, Fifi intensified into a hurricane and reached peak winds of 85 mph (137 km/h), around the same time that it passed about 150 mi (240 km) northeast of the Leeward Islands.[1] Later, Fifi began weakening, and by September 8 it was downgraded to tropical storm status.[12] The westerlies turned Fifi to the northeast on September 10.[1] After passing southeast of Bermuda, the storm dissipated on September 11.[12]

Tropical Storm Gerda

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 14 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 1001 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave was first observed on September 11 about 400 mi (640 km) east of the Lesser Antilles. It moved westward, and based on surface reports from the island chain, a tropical depression developed west of Martinique on September 13.[1] The system moved quickly to the west-northwest, becoming a tropical storm by late on September 13.[12] The Hurricane Hunters encountered winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) on September 14 just offshore the Dominican Republic; on that basis the system was designated Tropical Storm Gerda. Shortly thereafter, the storm struck the Barahona peninsula. The high terrain of Hispaniola quickly weakened Gerda, and on September 15 the Hurricane Hunters could not detect a closed circulation.[1] It is estimated that Gerda dissipated offshore southeastern Cuba.[12] The wave continued west, later reaching the Gulf of Mexico. Aided by an approaching trough, a small low pressure area redeveloped on September 19, which struck southern Texas and moved to the northeast. This low eventually dissipated over Louisiana on September 22, having produced gusts of 52 mph (84 km/h) along the Texas coast.[1]

When the precursor to Gerda passed through the Lesser Antilles, it dropped 15 in (380 mm) of rain.[28] Stations in the United States Virgin Islands reported winds up to 46 mph (74 km/h).[29] The storm's threat prompted gale warnings along the southern coast of Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic.[1] In the former island, Gerda killed three people. Two people drowned after falling off a boat on Vieques island, and the other died after his house collapsed while he was inside. The storm damaged coffee, banana, and plantain crops in Puerto Rico. Winds reached 54 mph (87 km/h) in the Dominican Republic.[30]

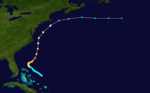

Hurricane Helene

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 21 – September 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min) 930 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave was first observed near Cape Verde on September 16. On September 21, the Hurricane Hunters observed a circulation, which indicated a tropical depression had formed east of the northern Leeward Islands. It moved to the west-northwest,[1] becoming Tropical Storm Helene on September 23.[31] The next day Helene became a hurricane, aided by an anticyclone aloft. It moved around a large ridge, bringing its center toward the southeastern United States. As the hurricane approached the Carolinas, the hurricane rapidly intensified as the eye became visible on radar, and Helene reached peak winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) on the morning of September 27.[1][12] An approaching trough turned the hurricane to the northeast, and Helene came within 10 mi (15 km) of the coast of North Carolina.[1] It slowly weakened, and at the same time its size expanded.[31] On September 29, Helene became extratropical as it was moving over Newfoundland. The remnants continued to the northeast, later turning to the southeast and dissipating on October 4 just west of Great Britain.[12]

While paralleling the southeastern United States, Helene produced a peak storm surge of 6 ft (1.8 m) near Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point in North Carolina. A station in Wilmington reported sustained winds of 88 mph (142 km/h) and a peak gust of 135 mph (220 km/h), exceeding the previous record for measured wind speed there by a wide margin. At Cape Fear, winds were estimated at 125 mph (200 km/h), with gusts as high as 160 mph (260 km/h).[1] Rainfall from Helene peaked at 8.29 in (211 mm) in Wilmington International Airport, although rainfall spread as far north as New England.[32] Damage in the United States totaled $11.2 million, and there was one indirect fatality.[1] In Atlantic Canada, Helene produced high winds and heavy rainfall,[33] causing power outages in Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton Island.[33][34] A wharf in Caribou, Nova Scotia was destroyed by rough seas generated by Helene, and at least 1,000 lobster traps were carried out to sea as a result.[35]

Hurricane Ilsa

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 24 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) 956 mbar (hPa) |

On September 24, ship reports near an area of disturbed weather east of the Lesser Antilles prompted a Hurricane Hunters flight. By the time the aircraft investigated the system, they discovered a tropical storm with winds of 40 mph (64 km/h), which was named Ilsa by the Weather Bureau.[1] Subsequent analysis estimated that the storm became a tropical depression earlier that day.[12] Ilsa quickly intensified into a hurricane on September 25, by which time it was located about 1,100 mi (1,800 km) southeast of Hurricane Helene. Over the subsequent few days, the two hurricanes underwent the Fujiwhara effect, in which Ilsa turned to the north and Helene turned to the northeast. Ilsa quickly intensified on September 26, developing a well-defined eye and spiral rainbands.[1] Early on September 27, it reached peak winds of 110 mph (175 km/h), and subsequently it weakened. On September 29 the hurricane turned to the northeast and accelerated, becoming extratropical and dissipating by the next day.[12]

Early in the duration of Ilsa, the Weather Bureau issued a gale warning and hurricane watch for the Leeward Islands, Virgin Islands, and northern Puerto Rico.[36] However, no damage was reported.[1] The storm caused extensive beach erosion and squally conditions in Bermuda.[37]

Hurricane Janice

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 4 – October 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min) 968 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved through the Lesser Antilles on September 30. It moved westward through the Caribbean, developing a broad circulation by October 3 as it approached Jamaica. The weak circulation gradually became better organized,[1] developing into a tropical depression near the Cayman Islands on October 4.[12] The system quickly intensified into Tropical Storm Janice as it moved toward the coast of Cuba. An eastward-moving cold front turned the storm to the north and northeast, and Janice crossed central Cuba early on October 6. The storm intensified while moving through the Bahamas, becoming a hurricane on October 7. Janice slowed that day and reached peak winds of 100 mph (155 km/h). On October 9, the hurricane turned to the east-northeast, and by that time had weakened slightly; however, the next day it re-attained its previous peak intensity while passing northwest of Bermuda, reaching a minimum pressure of 968 mbar (28.6 inHg).[1] On October 12, Janice became extratropical in the northern Atlantic Ocean, and the next day merged with a stronger non-tropical low offshore Atlantic Canada.[1][12]

The precursor to Janice dropped heavy rainfall in Jamaica, reaching over 20 in (510 mm) in some locations. Rain-induced flooding destroyed homes, wrecked crops, and damaged coastal wharves and roads.[1] Eight people were killed, and the floods were considered the worst in 25 years.[38] When Janice was still over Cuba, the Weather Bureau issued gale warnings from Vero Beach, Florida to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. In the Bahamas, Janice produced peak winds of 63 mph (101 km/h) on San Salvador Island. In Nassau, one person was killed while trying to move a boat. A dredger was lost and a yacht was seriously damaged in the Bahamas, and damage in the country reached $200,000.[1]

Tropical Storm Twelve

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 15 – October 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1004 mbar (hPa) |

A low pressure area developed north of Hispaniola from a dissipating cold front, organizing into a tropical depression on October 15. The system moved to the north-northeast, attaining peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h), based on reports from ships. On October 17, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone as it interacted with an approaching cold front. The storm continued northeastward, merging with a larger storm on October 19 to the south of Atlantic Canada.[39]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms (tropical storms and hurricanes) that formed in the North Atlantic in 1958.[40]

|

|

See also

- 1958 Pacific hurricane season

- 1958 Pacific typhoon season

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- Atlantic hurricane season

References

- "The Hurricane Season of 1958" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Miami Weather Bureau Office. 86: 477–485. December 1958. Bibcode:1958MWRv...86..477.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1958)086<0477:thso>2.0.co;2. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Dick Bothwell (1958-05-30). "Miami Weather Chief Checks Warning System". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Jack W. Roberts (1958-06-15). "Hurricane Season On; Bureau Set". The Miami News. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- "First Woman to Fly into Eye of Hurricane Calls It 'Lovely Sight'". The Ocala Star-Banner. Associated Press. 1958-08-28. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- Alexander Sadowski (September 1959). "Atlantic Coastal Radar Tracking of 1958 Hurricanes". Journal of Geophysical Research. 64 (9): 1277–1282. Bibcode:1959JGR....64.1277S. doi:10.1029/jz064i009p01277. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- Hurricane Research Division (March 2011). "Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- David Levinson (2008-08-20). "2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- John R. Clark; William O. French (May 1958). "Some Interesting Aspects of a Subtropical Depression May 18–28, 1958" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. United States Weather Bureau. 86: 186–196. Bibcode:1958MWRv...86..186C. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1958)086<0186:siaoas>2.0.co;2. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- James F. Andrews (May 1958). The Weather and Circulation of May 1958 (PDF). Monthly Weather Review (Report). United States Weather Bureau. p. 181. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- "Over One Foot of Water Falls on Miami Area". Ocala Star-Banner. Associated Press. 1958-05-25. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- Preliminary Report on Tropical Storm Alma June 14–15, 1958 (GIF) (Report). United States Weather Bureau. 1958-06-17. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- "Storm Drops Deluge Over Inland Texas". The Spokesman-Review. 1958-06-17. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- "Texas Flash Floods Drop; Tornado Funnels Appear". The Spokesman Review. Associated Press. 1958-06-18. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- "20 Inch Rain Wets Texas". The Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. 1958-06-18. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Ralph L. Higgs (1958-08-12). Advisory Number 1 Becky (GIF) (Report). San Juan Weather Bureau. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Ralph L. Higgs (1958-08-21). Report on Storm Becky – August 12–13, 1958 (GIF) (Report). San Juan Weather Bureau. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Preliminary Report on Tropical Storm Becky August 11–15, 1958 (GIF) (Report). United States Weather Bureau. 1958-08-18. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Ralph L. Higgs (1958-08-14). Hurricane Advisory Number 1 Cleo (GIF) (Report). San Juan Weather Bureau. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- "1958-Cleo". Environment Canada. 2009-11-12. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

- Preliminary Report on Hurricane Daisy August 24–29, 1958 (GIF) (Report). United States Weather Bureau. 1958-09-08. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- Jack D. Tracy (May 1966). "Correction to the Article "The Hurricane Season of 1958"" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 94 (5): 327. Bibcode:1966MWRv...94..327T. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1966)094<0327:cttath>2.3.co;2. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Roth, David M.; Weather Prediction Center. "Hurricane Daisy – August 27–30, 1958". Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- "New England Spared Wrath of Hurricane". The Washington Observer. Associated Press. 1958-08-30. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- 1958-Daisy (Report). Environment Canada. 2009-11-12. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- "Ella Hits Cuba; Gale And Rain On Florida Keys". Meriden Journal. United Press International. 1958-09-03. p. 7. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- Ralph L. Higgs (1958-09-19). Report on Hurricane Fifi – September 5–7, 1958 (GIF) (Report). San Juan Weather Bureau. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Ralph L. Higgs (1958). Report of Tropical Storm Gerda (GIF) (Report). San Juan Weather Bureau. p. 2. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Ralph L. Higgs (1958). Report of Tropical Storm Gerda (GIF) (Report). San Juan Weather Bureau. p. 3. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Ralph L. Higgs (1958). Report of Tropical Storm Gerda (GIF) (Report). San Juan Weather Bureau. p. 5. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Hurricane Helene September 23–29, 1958 (PDF) (Report). United States Weather Bureau. 1958-09-30. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Roth, David M. "Hurricane Helene – September 25–29, 1958". Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- "1958-Helene". Storm Impact Summaries. Environment Canada. 2010-09-14. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- "Helene Batters Nfld". Saskatoon Star-Phoenix. Sydney, Nova Scotia. The Canadian Press. 1958-09-30. p. 2. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- Suri, Dan. "Dan, Dan the Weatherman's Canadian Weather Trivia Page". Archived from the original on 2013-09-09. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- Ralph L. Higgs (1958-10-13). Report on Hurricane Ilsa (GIF) (Report). San Juan Weather Bureau. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Mark Guishard; James Dodgson; Michael Johnston (May 2015). "Hurricanes - General Information for Bermuda". Bermuda Weather Service. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2015.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "8 Drown". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. 1958-10-08. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- Sandy Delgado; Chris Landsea (July 2016). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (1956) (PDF) (Report). Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- Gary Padgett. "History of the Naming of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Part 1 – The Fabulous Fifties". Archived from the original on 2010-10-07. Retrieved 2013-03-06.