1953 Atlantic hurricane season

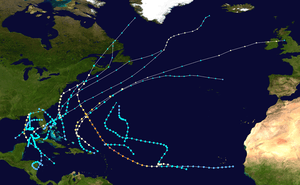

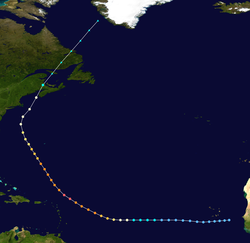

The 1953 Atlantic hurricane season was the first time an organized list of female names was used to name Atlantic storms. It officially began on June 15,[1] and lasted until November 15,[2] although activity occurred both before and after the season's limits. The season was active with fourteen total storms, six of which developed into hurricanes; four of the hurricanes attained major hurricane status, or a Category 3 or greater on the Saffir-Simpson scale.

| 1953 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 25, 1953 |

| Last system dissipated | December 9, 1953 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Carol |

| • Maximum winds | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 929 mbar (hPa; 27.43 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 19 |

| Total storms | 14 |

| Hurricanes | 7 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 14+ |

| Total damage | $3.75 million (1953 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The strongest hurricane of the season was Carol, although by the time it struck Atlantic Canada it was much weaker. Both hurricanes Barbara and Florence struck the United States; the former crossed the Outer Banks and impacted much of the east coast, and Florence struck a sparsely populated region of the Florida Panhandle without causing much damage. Bermuda was threatened by three hurricanes within two weeks. In addition to the hurricanes, Tropical Storm Alice developed in late May and left several fatalities in Cuba. The final hurricane of the season, Hazel, produced additional rainfall in Florida after previous flooding conditions. There were several unnamed storms, the last of which dissipated on December 9.

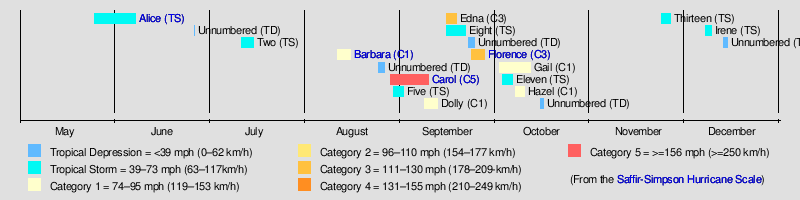

Timeline

Systems

Tropical Storm Alice

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 25 – June 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 994 mbar (hPa) |

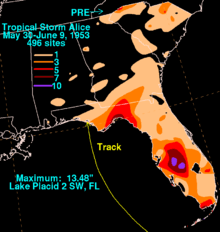

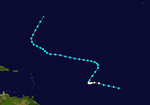

A tropical storm developed east of Nicaragua on May 25, executing a counterclockwise loop over Central America. After weakening over land, Alice re-intensified over the western Caribbean, moving over western Cuba on May 21 with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h). On June 1, it entered the Gulf of Mexico, and later executed another loop off the northwest coast of Cuba.[3] Alice quickly weakened due to a cold front,[4] and advisories were discontinued by June 3.[5] While near Cuba, Alice produced drought-breaking rainfall that caused flooding and several unofficial drowning deaths.[3]

After passing near Cuba, Alice turned to the north and restrengthened to peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h), possibly even stronger to hurricane intensity. Alice again weakened before making landfall near Panama City Beach on June 6 as a minimal tropical storm, and dissipating shortly thereafter.[3] Alice brought heavy rainfall to Florida, peaking at 13.48 inches (342 mm) in Lake Placid. Near where it made landfall, the storm dropped light rainfall, and there were no reports of damage in the state.[6][3] Alice was the first North Atlantic tropical cyclone to have a female name.[7] It was also one of 22 tropical or subtropical cyclones on record in the month of May.[8]

Tropical Storm Two

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 11 – July 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 1005 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression developed over southwestern Florida on July 11. It moved northeastward toward a trough across northern Florida. The depression intensified into a tropical storm on July 12 and reached peak winds of 45 mph (75 km/h). On July 15, the storm began interacting with a nearby cold front, signaling that it transitioned into an extratropical storm. On the next day, the storm brushed Nantucket with 31 mph (50 km/h winds before the storm was absorbed by the front.[9]

Hurricane Barbara

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 11 – August 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 973 mbar (hPa) |

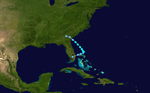

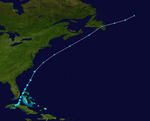

A tropical wave developed into Tropical Storm Barbara over the Bahamas on August 11. It intensified as it moved north-northwestward, becoming a hurricane by the next day,[3][10] and reaching peak winds of 90 mph (150 km/h) just south of Cape Hatteras on August 13.[8] Barbara moved over the Outer Banks, passing between Morehead City and Ocracoke, and it turned and accelerated to the northeast. Steadily weakening and losing tropical characteristics, the hurricane transitioned into an extratropical cyclone late on August 15. It turned northward, crossing eastern Nova Scotia and dissipating over Labrador on August 16.[10][8]

Before Barbara struck the Outer Banks, officials ordered evacuations for a few islands, and several thousand tourists voluntarily left the region.[11] Wind gusts reached 90 mph (140 km/h) at Hatteras and Nags Head. Torrential rainfall fell across the state and extended northward into Virginia,[10] peaking at 11.1 in (280 mm) near Onley along the Eastern Shore of Virginia.[12] Across the region, the hurricane left flooding and downed trees,[11] some of which survived the Great Atlantic Hurricane of 1944.[10] Monetary damage from Barbara was estimated around $1.3 million (1953 USD, $12.4 million 2020 USD),[13] mostly from the crop damage.[14] Newspaper reports indicated there were seven deaths in the country;[14] two additional deaths occurred offshore Atlantic Canada when a dory sunk.[15]

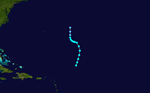

Hurricane Carol

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 28 – September 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-min) 929 mbar (hPa) |

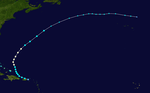

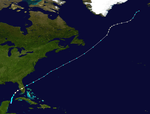

On August 28, a tropical wave developed into a tropical depression near Cape Verde. After moving west-southwestward, it turned to the northwest, intensifying into a tropical storm on August 31 and into a hurricane on September 2. Passing northeast of the Lesser Antilles, Carol rapidly intensified to Category 5 intensity, reaching peak winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) on September 3, making it the strongest hurricane of the season.[3][8] It gradually weakened, bypassing Bermuda on September 6 and producing high waves.[8][16] Carol later turned to the north-northeast, brushing Cape Cod and causing boating accidents across New England. Four people were killed in the region.[8][17] Fishing losses totaled around $1 million (1953 USD, $9.56 million 2020 USD).[3]

After bypassing New England, Carol brushed western Nova Scotia before moving ashore near Saint John, New Brunswick as a minimal hurricane.[18] As it moved ashore, it produced hurricane conditions in eastern Maine, one of only six Atlantic hurricanes to do so.[19] In Nova Scotia, several boats were wrecked or washed ashore, with one drowning death reported. High seas caused coastal flooding, while strong winds downed large areas of trees. Heavy losses to the apple crop occurred in Annapolis Valley, totaling $1 million (1950 CAD, $9.88 million 2020 USD).[18] Carol later dissipated southwest of Greenland on September 9.[8]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 29 – September 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min) 1007 mbar (hPa) |

On August 29, a tropical storm developed over southern Florida.[8] While moving through the state, the storm dropped heavy rainfall, reaching 4.67 in (119 mm) at Fort Lauderdale Beach; similar rainfall was observed in the northern Bahamas. Described by one Weather Bureau forecaster as "wide and flat", the storm gradually organized over the western Atlantic Ocean.[20] On August 31, the storm turned to the northwest, with maximum sustained winds of 40 mph (65 km/h). The system weakened to a tropical depression before moving ashore near Savannah, Georgia on September 1. It dissipated that day over land.[8]

Hurricane Dolly

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 8 – September 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 989 mbar (hPa) |

The origins of Dolly were from a tropical wave that moved through the eastern Caribbean Sea,[3] producing 10 in (250 mm) in Saint Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands. The rains closed schools and government buildings around San Juan, Puerto Rico, and flooding was reported in Guayama, Yabucoa, and Patillas.[21] On September 8, a tropical storm developed north of Puerto Rico, which moved slowly west-southwestward before turning to the north.[8] It quickly intensified, and after Hurricane Hunters reported an eye, Dolly reached hurricane status on September 9. At that time, hurricane warnings were issued in the Bahamas, although the storm turned away from the archipelago.[13][8] It intensified to peak winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) on September 10, as reported by aircraft.[3]

Dolly weakened as it accelerated northeastward, although it still threatened to strike Bermuda with strong winds. As a result, the United States Air Force ordered all of the planes on the island to fly to the mainland.[22] After continued weakening, Dolly passed over the island on September 11, producing only gale-force winds, rains, and little to no damage.[3][23] It deteriorated into a tropical storm on September 12 and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone later that day. The remnants of Dolly later turned eastward, dissipating just west of Portugal on September 17.[8]

Hurricane Edna

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 15 – September 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) 962 mbar (hPa) |

Shortly behind Dolly, another tropical wave spawned a tropical depression over the Lesser Antilles on September 15.[3] As it moved through the region, it produced unsettled conditions across the northeast Caribbean.[24] Edna quickly intensified as it tracked northwestward, attaining hurricane status on September 15 and peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) the next day. After peaking, the hurricane turned to the northeast and maintained most of its intensity for a few days.[3] It passed just north of Bermuda early on September 18 with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h), before beginning a steady weakening trend as it accelerated. By September 19, Edna completed the transition into an extratropical cyclone, lasting another day before dissipating west of Ireland.[8]

Before Edna struck Bermuda, the islanders were well-prepared due to being previously impacted by hurricanes Carol and Dolly, and they boarded up their homes.[25] The hurricane caused "considerable damage", with wind gusts reaching 120 mph (190 km/h).[3] The winds downed trees, blocking roads, and also caused disruptions to the power and water services.[26] During its passage, Edna produced heavy rainfall and also damaged several roofs. There were three injuries on the island.[23]

Tropical Storm Eight

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 15 – September 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression formed in the central Gulf of Mexico on September 15 and moved northeastward.[8] The storm produced heavy seas across the region, which damaged two small boats.[27] The storm reached peak winds of 50 mph (75 km/h) while moving in a small clockwise loop southeast of Louisiana. The storm weakened into a tropical depression on September 17, but re-intensified to a tropical storm three days later. On September 20, the storm moved ashore in Taylor County, Florida and dissipated the next day over the state, bringing 2 to 5 in (51 to 127 mm) of rainfall to coastal areas.[8][9]

Hurricane Florence

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 23 – September 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 968 mbar (hPa) |

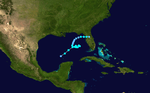

Florence developed on September 23 near Jamaica from a tropical wave.[3] While passing that island, it produced heavy rainfall that blocked roads.[28] It intensified to hurricane status on September 24 while passing through the Yucatán Channel,[3] and while doing so left heavy damage in western Cuba.[29] After turning north and entering the Gulf of Mexico, Florence quickly intensified to peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). It gradually weakened before making landfall on September 26 as a minimal hurricane in a sparsely populated region of the Florida Panhandle.[8]

Before Florence hit the United States Gulf Coast, about 10,000 people evacuated Panama City, Florida,[30] and the Weather Bureau issued timely warnings that was credited in preventing any deaths or major injuries.[3] Winds reached 84 mph (135 km/h) at Eglin Air Force Base,[31] and the heaviest rainfall was 14.71 in (374 mm) in Lockhart, Alabama.[32] The combination of winds and heavy rainfall left crop damage in the Florida panhandle and southeastern Alabama, although coastal damage was not severe. Overall, 421 houses were damaged and another three were destroyed, with monetary damage estimated around $200,000 (1953 USD, $1.91 million 2020 USD).[3] After landfall, Florence quickly transitioned into an extratropical cyclone, and as it continued across the southeastern United States it produced moderately heavy rainfall. It dissipated on September 28 southeast of New England.[32][8]

Hurricane Gail

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 2 – October 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 986 mbar (hPa) |

On October 2, a tropical wave spawned a tropical depression about 815 mi (1310 km) west-southwest of the Cape Verde islands. The depression quickly intensified into Tropical Storm Gail, and the next day, a ship encountered the storm, reporting a minimum pressure of 986 mbar (29.12 inHg). As the ship crossed through the center, it reported winds of 80 mph (130 km/h), indicating Gail attained hurricane status. Initially, the Weather Service believed that Gail dissipated and a new storm formed in the same region on October 5, but a reanalysis in 2015 indicated that they were the same storm. The confusion resulted from Gail turning to the northeast on October 4, steered by an approaching trough. On October 6, Gail turned back to the west-northwest, remaining a moderate tropical storm for several days. On October 11, the cold front that absorbed Hurricane Hazel turned Gail to the north, and absorbed it the next day in the central Atlantic.[3][8][9]

Tropical Storm Eleven

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 3 – October 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 1001 mbar (hPa) |

On October 3, a tropical storm developed near the southern coast of Cuba. It moved northwestward, crossing the island before turning to the northeast. Early on October 5, the storm brushed southeastern Florida,[8] producing gusty winds and rainfall. The threat of the storm prompted small craft warnings from the Florida Keys through South Carolina.[33] As it accelerated northeastward, the storm strengthened slightly to maximum sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h), before becoming extratropical on October 6. Two days later, the remnants moved over Atlantic Canada with winds of 70 mph (120 km/h),[8] producing flooding rainfall that washed out several roads. The storm caused two deaths after it wrecked a boat in Broad Cove, Nova Scotia.[34] Later, the cyclone passed south of Greenland before dissipating southwest of Iceland on October 10.[8]

Hurricane Hazel

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 7 – October 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 980 mbar (hPa) |

The twelfth tropical storm and the final hurricane of the season formed in the Yucatán Channel on October 7. Given the name Hazel, the storm tracked north-northeastward, then northeastward through the Gulf of Mexico while gradually intensifying. On October 9, Hazel strengthened into a hurricane made landfall just north of Fort Myers, Florida at its peak intensity of 85 mph (140 km/h). The storm crossed the state in about six hours, during which it weakened slightly back to a tropical storm. Over the western Atlantic Ocean, Hazel re-intensified to its peak winds, although by late on October 10 it transitioned into an extratropical storm between North Carolina and Bermuda. The remnants continued northeastward, dissipating southeast of Newfoundland on October 12.[3][8] On Sable Island, the storm produced heavy winds and rain.[35]

Due to the fairly light winds across Florida, damage from Hazel was minor, estimated around $250,000 (1953 USD, $2.39 million 2020 USD). During its passage, the storm spawned a tornado in St. James City that destroyed several homes, and there were indications of another tornado in Okeechobee City. The primary impact from Hazel was from its rainfall,[3] peaking at 10.53 inches (267 mm) in Daytona Beach.[36] The rains added to previous flooding conditions across the state, causing a record flood stage along the St. Johns River that flooded 6 mi (9.7 km) of highway. Overall flooding damage was estimated up to $10 million (1953 USD, $95.6 million 2020 USD), but it was impossible to determine how much was due to Hazel.[3]

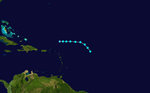

Tropical Storm Thirteen

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 23 – November 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 999 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm developed from a dissipating cold front on November 23, about 460 mi (740 km) northeast of Barbuda in the Lesser Antilles. It moved northeastward, strengthening to peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) on November 24. It later turned sharply to the west as it began a weakening trend, followed by a curve to the north. The cyclone dissipated on November 26 about 450 mi (725 km) east-northeast of Bermuda, without ever affecting land.[8]

Tropical Storm Irene

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | December 7 – December 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 999 mbar (hPa) |

The final tropical cyclone of the season developed on December 7 about 705 mi (1735 km) east-northeast of the Lesser Antilles, from the end of a dissipating cold front. Given the name Irene, the storm moved to the northwest and later to the west. Based on ship observations, it is estimated that Irene intensified to a peak of 65 mph (100 km/h) on December 8, before weakening the next day. Late on December 9, Irene dissipated about 270 mi (435 km) north of the Lesser Antilles.[8][9]

Storm names

These names were used to name storms during the 1953 season. The list was the same for the 1954 season as well. Initially, all female names were used; it was not until the 1979 season that male and female names were used in alternating order. Names that were not assigned are marked in gray. All storm names were named for the first time.[37] No names were retired, because the World Meteorological Organization only started to retire storm names in the next year, 1954.

|

|

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- List of off-season Atlantic hurricanes

References

- Staff Writer. "Tiny Hurricane Training Medium for Observers". The Times-News. United Press. Retrieved 2011-02-08.

- Staff Writer (1954-11-14). "Hurricane Season Closes Tonight, Scores Better Than Average". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-02-08.

- Grady Norton (1953). "Hurricanes of 1953" (PDF). Miami Weather Bureau Office. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- United Press International (1953-06-03). "Cold Gulf Air Cools 'Cane Alice". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Google News Archive. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- Staff Writer (1953-06-03). "Storm 'Alice' Fizzles in Gulf". Palm Beach Post. Google News Archive. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in Florida". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- United Press International (1953-06-01). "Tropical Storm Whips Cuban Coast". Reading Eagle. Google News Archive. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Chris Landsea; et al. (May 2018). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (1953) (Report). Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- R. P. James and C. F. Thomas (August 1953). "Hurricane Barbara, 1953" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- Staff Writer (1953-08-13). "Vacationers Flee Carolina Hurricane". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- David M. Roth (2011-02-07). "Rainfall Summary of Hurricane Barbara" (JPG). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- Staff Writer (1953-08-15). "Storm Turns Out to Sea, 7 Lose Lives". The Miami News. United Press. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- Staff Writer (1953-08-14). "Hurricane Veers into Atlantic After Killing 7 Along Coast". The Daily Times. United Press. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- Canadian Hurricane Centre (2010-11-09). "1953-Barbara". Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- Staff Writer (1953-09-05). "Edge of Hurricane Buffets Bermuda". The Pittsburgh Press. United Press. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- Staff Writer (1953-09-07). "Four New England Drownings Due to Carol". Lawrence Journal. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- Canadian Hurricane Centre (2010-09-14). "1953-Carol". Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- Hurricane Research Division (December 2010). "Chronological List of All Hurricanes which Affected the Continental United States: 1851-2010" (TXT). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- Staff Writer (1953-08-29). "Another Area of Suspicion Found on Florida Coast". Times Daily. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

- Staff Writer (1953-09-10). "Rain Part of Tropical Storm in Area". The Virgin Islands Daily News. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- Staff Writer (1953-09-12). "New Storm Bears Down on Bermuda". Schenectady Daily Times. United Press. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- "Hurricanes - General Information for Bermuda" (DOC). Bermuda Weather Service. May 2007. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- Staff Writer (1953-09-14). "Atlantic Storm Gathers Force". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- Staff Writer (1953-09-18). "Bodacious Edna Blasts Bermuda". Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- Staff Writer (1953-09-18). "Hurricane Hits Bermuda, Moves On To Shipping Lanes". The Miami News. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- Staff Writer (1953-09-15). "Tropical Storm Believed Brewing in Gulf of Mexico". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- Staff Writer (1953-09-24). "Jamaica Warned of Nearby Hurricane". St. Joseph Gazette. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- David Longshore (2008). Encyclopedia of hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones. Facts on File, Inc. p. 186. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- E. L. Quarantelli (May 1982). Inventory of Disaster Field Studies in the Social and Behaviroal Sciences 1919 - 1979 (PDF) (Report). University of Delaware. p. D-9. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- Staff Writer (1953-09-27). "Hurricane Florence Dies Over Northwest Florida". St. Petersburg Times. United Press. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- David M. Roth (2008-09-23). "Hurricane Florence - September 24-28, 1953". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- Staff Writer (1953-10-04). "7th Hurricane Grows; Florida Area Watched". United Press. Retrieved 2011-02-04.

- "1953-NN-3". Environment Canada. 2009-11-09. Retrieved 2011-02-04.

- "Hazel-1953". Environment Canada. 2009-11-09. Retrieved 2011-02-04.

- David M. Roth (2010-08-17). "Tropical Storm Hazel - October 6-10, 1953". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- Gary Padgett (June 2007). "History of the Naming of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, Part 1 - The Fabulous Fifties". Australian Severe Weather. Retrieved 2011-02-08.