U Street

The U Street Corridor, sometimes called Cardozo/Shaw or Cardozo, is a commercial and residential district in Northwest Washington, D.C., most of which also constitutes the Greater U Street Historic District. It is centered along a nine-block stretch of U Street from 9th to 18th streets NW, from the 1920s until the 1960s was the city's black entertainment hub, called "Black Broadway"[3] and "the heart of black culture in Washington, D.C.".[4] After a period of decline following the 1968 riots, the economy picked up with the 1991 opening of the U Street metro station. With subsequent gentrification the population diversified and as of 2017 is est. 67% non-Hispanic White and 18% African American.[5] Since 2013, thousands of new residents have moved into large new luxury apartment buildings. U Street is now promoted as a "happening" neighborhood for upscale yet "hip" and "eclectic" dining and shopping, its live music and nightlife, as well as one of the most significant African American heritage districts in the country.[4]

U Street Corridor, Washington, D.C. | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood of Washington, D.C. | |

| Coordinates: 38.917046°N 77.03293°W | |

| Country | United States |

| District | Washington, D.C. |

| Ward | Ward 1 |

| Government | |

| • Councilmember | Brianne Nadeau (Ward 1) |

| Area | |

| • Total | .2 sq mi (0.5 km2) |

| Population (2017) | |

| • Total | 5,385 |

| • Density | 26,732/sq mi (10,321/km2) |

| Website | https://washington.org/dc-neighborhoods/u-street |

Greater U Street Historic District | |

G. Byron Peck's Duke Ellington mural on the True Reformer Building, as seen from across the street at Ben Ali Way — named for the late owner of Ben's Chili Bowl. | |

| |

| Location | Roughly bounded by New Hampshire Avenue, Florida Avenue, 6th Street, R Street, and 16th Street, NW Washington, D.C. |

|---|---|

| Architectural style | Art Deco, Neoclassicism, Italianate, Queen Anne, Renaissance Revival, Romanesque Revival (approximately 1580 contributing properties)[1] |

| NRHP reference No. | 98001557[2] |

| Added to NRHP | December 31, 1998 |

Geography and name

The U Street Corridor is bounded by:

- on the north, Florida Ave. NW and Columbia Heights

- on the south, S St. NW and the Logan Circle and Shaw neighborhoods

- on the east, 9th St. NW and LeDroit Park, Howard University and the Shaw neighborhood

- on the west, 15th St. NW and the Adams Morgan and Dupont Circle neighborhoods and the Strivers' Section and Sixteenth Street historic districts

In addition to U Street itself, 14th Street is a major retail, dining and entertainment corridor. Retailers located on 14th near U include Room and Board, West Elm, and Lululemon.

Name and identity

The area is often referred to as U Street Corridor.[4][3] However, historically and contemporary, the area has been known by other names:

- Part of Shaw: The 1966 Shaw School Urban Renewal Area plan covered the neighborhood now commonly known as Shaw, but also the U Street Corridor, Logan Circle, that for decades were also considered part of Shaw.[6][7]

- Cardozo: in the 1990s the U Street Corridor was often referred to as Cardozo/Shaw,[7] a name that the DC planning department[8] still uses.[9] Google Maps labels the neighborhood Cardozo. In both cases this is defined as a neighborhood separate from the Shaw neighborhood proper. The Cardozo Education Campus is located adjacent to the U Street Corridor but is actually in Columbia Heights neighborhood.

History

1862–1900: Origins

U Street is a largely Victorian-era neighborhood, developed between 1862 and 1900, the majority of which has been designated as the Greater U Street historic district.

At the time of the Civil War, the area was woods and open fields. The Union command chose this area for military encampments including Camp Barker near 13th and R streets and others in what is now the Shaw neighborhood proper. The encampments were safe havens for freed slaves fleeing the South, and thus the area became a popular one for African Americans to settle.[10]

After the war, horse-drawn streetcar lines opened, running north from downtown Washington along 7th, 9th and 14th streets,[11] making the area an easily accessible place to live. The lines were later turned into cable cars. Both blacks and whites lived here, gradually shifting to a predominantly African American population between 1900 and 1920.[10]

The area's oldest buildings are Italianate, Second Empire and Queen Anne-style row houses built rapidly by speculative developers in response to the city's high demand for housing with the post-Civil War growth of the federal government.

1900–1968: "Black Broadway" and Hub of Black Washington

Until the 1920s, when it was overtaken by Harlem, the U Street Corridor was home to the nation's largest urban African American community.[12] The area was home to the Industrial Bank, the city's oldest African American-owned bank,[13] and to hundreds of black-owned and black-friendly businesses, churches, theaters, gyms, and other community spaces. Natives of the area included jazz musician Duke Ellington, opera singer Lillian Evanti, surgeon Charles R. Drew, and law professor Charles Hamilton Houston.[13]

In its cultural heyday – roughly consisting of the years between 1900 and the early 1960s[13] – the U Street Corridor was known as "Black Broadway", a phrase coined by singer Pearl Bailey.[14] Performers who played the local clubs of the era included Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Sarah Vaughan, Billie Holiday, and Jelly Roll Morton, among many others.[15] During Prohibition, U Street was also home to many of the capital's 2,000-3,000 speakeasies, which some historians credit for helping integrate a city long divided between black and white.[16]

From 1911 to 1963, the west end of the U Street neighborhood was anchored by Griffith Stadium, home of the District's baseball team, the Washington Senators. The Lincoln Theatre opened in 1921, and Howard Theatre in 1926.[17] Duke Ellington's childhood home was located on 13th street between T and S Streets.

The Green Book, a travel guide for black travelers (1933–1963) listed many sites along U Street NW by Green Book Travelers.[18]

1968–1986: Decline

While the area remained a cultural center for the African American community through the 1960s, the neighborhood began to decline following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968. The intersection of 14th Street and U Street was the epicenter of violence and destruction during the 1968 Washington, D.C. riots.[19] Following the riots, and the subsequent flight of affluent residents and businesses from the area, the corridor became blighted.[20] Drug trafficking rose dramatically in the mid-1970s, when the intersection of 14th and U Streets was an area of drug trafficking in Washington, D.C.[21]

1986-2010: Redevelopment and demographic change

Following the economic downturn the area faced following the 1968 riots, the community and DC government launched numerous redevelopment efforts.

Examples include:[22]

- The Reeves Center, built in 1986 at 14th and U, which houses city agencies and represented a $50 million investment, and which includes an urban plaza and weekly farmer's market

- Metro and bus stops on U Street for increased accessibility by transit

- Capital Bikeshare stations

- 1998 Department of Housing and Urban Development grants funding "Remembering U Street" signage marking 15 historic properties, as well as façade improvements to 150 dilapidated storefronts on U and 14th streets

- New construction and rehabilitation projects providing more quality, affordable housing, including Section 8-qualifying units and senior citizen communities.

In the 1990s, revitalization of Adams Morgan and later Logan Circle began. More than 2,000 luxury condominiums and apartments were constructed between 1997 and 2007. As the area improved and became more attractive Washingtonians of all races and ethnicities, and of higher incomes and wealth, to live there, the ethnic mix of the neighborhood changed dramatically: in 2000 it was roughly 20% white and 60% black; while by 2010 that had reversed and the it was roughly 60% white and 20% black (see Demographics below).[23]

U Street Corridor today

Redevelopment continued further into the 2000s and 2010s,[20] along with rising concerns about gentrification.[24]

Since 2013, more than 700 residential units have been added to the neighborhood in large luxury buildings with street-level retail. This represents a significant population increase versus the population of 4,572 registered in the 2010 census.

In 2011, U Street NW was designated a Great Street among Great Places in America by the American Planning Association. It is said to have been selected for in recognition of the street return to its grandeur after several decades of difficulties. Once again, the street hosts the arts, food, and businesses. The community works to embrace its historical significance for the African American community of Washington, D.C. during segregation.[25]

1923 14th St NW before 2014-8 renovation

1923 14th St NW before 2014-8 renovation 1923 14th St NW after renovation

1923 14th St NW after renovation Retail and new apartment buildings along 14th Street, 2019

Retail and new apartment buildings along 14th Street, 2019 Retail on east side of 14th Street between S and T streets

Retail on east side of 14th Street between S and T streets Obama mural in U Street alley

Obama mural in U Street alley Row house at 13th and Wallach with taller new buildings rising in the background, 2010s

Row house at 13th and Wallach with taller new buildings rising in the background, 2010s Commercial buildings on the 1600 block

Commercial buildings on the 1600 block

Historic landmarks and architecture

The neighborhood's landmark buildings are nearly all the works of prominent early 20th century African American architects, including:[26]

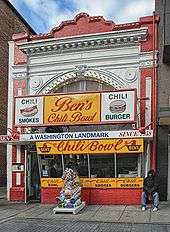

- Ben's Chili Bowl (1213 U Street NW), housed in the former Minnehaha nickelodeon theater (P. A. Hurlehaus, 1909, NRHP-listed) staying open during the 1968 riots, Ben's Chili Bowl continues to host customers and serve local residents.[27]

- True Reformer Building (1200 U Street NW) by John A. Lankford, then known as the "Dean of Black Architecture", built in 1902, NRHP-listed. It is an "architectural testament to black economic development" as headquarters of the Grand United Order of True Reformers, which offered members insurance that white-owned firms would not sell them.[28]

- Industrial Savings Bank (11th and U) by Isaiah T. Hatton, 1917

- Prince Hall Masonic Temple (1000 U Street NW) by Albert Cassell, 1922.

- The Thurgood Marshall Center in the Twelfth Street YMCA Building (William Sidney Pittman, 1912; NRHP-listed) is a community center that displays and preserves the stories of African American leaders and communities that faced discrimination through history; Previously it housed the first African American YMCA.

- The Whitelaw Hotel (Isaiah T. Hatton, 1919; NRHP-listed) served well-known entertainers who were performing near U Street as well as African American visitors drawn to Washington for meetings of national black organizations, all of whom were unable to rent rooms in the city's luxury hotels because of discrimination and segregation. Guests included Joe Louis, Benny Carter, Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington. It closed as a hotel in 1977 and reopened as an apartment building in 1992.[28]

Other landmarks include:

- Lincoln Theatre, opened in 1922 as one of the largest integrated movie houses and ballrooms, closed in 1983. The theatre was placed on the NRHP in 1993, and was renovated and reopened in 1994 as a performing arts center.[29] The Lincoln Colonnnade was a public hall behind and below the theater, hosting balls and other events.

- Duke Ellington's former residences at 1805 and 1816 13th Street NW, where the artist spent his teenage years (1910-1917)

Cultural Tourism DC has placed signs on a self-guided Greater U Street neighborhood heritage trail and operates the Greater U Street Visitor Center at 1211 U Street NW.[6]

Music, arts and culture

.jpg)

U Street has long been a center of Washington's music scene, with the Lincoln Theatre (1922), Howard Theatre, Bohemian Caverns (1926), and other clubs like on 9th Street at Harrington's, and Chez Maurice Restaurants and historic jazz venues. The 9:30 Club, the Black Cat, DC9, U Street Music Hall, and the Velvet Lounge musical venues are located on the corridor, which is also home to the D.C. music collective Spelling for Bees.[30] U Street also hosts the annual Funk Parade, a festival and celebration of funk music, community arts, and creativity. Public art, street art or graffiti and murals can be found on almost every corner along U Street.

Economics

Residential

Since 2013 numerous large mixed use residential buildings with retail on the ground floor have been built into the corridor including:[31]

- 13|U (2017, 129 units, 16,000 sq. ft. of retail including RiteAid drugstore branch and restaurant The Smith)[32][33]

- The District (2013, 125 units, Ted's Bulletin restaurant)

- Elysium Fourteen (2016, 56 units residential, Lululemon and Orange Fitness branches)

- Louis at 14th (2014, sold for $76 million, 268 units residential, Trader Joe's supermarket)[34]

- The Harper (2014, 144 units, Madewell clothing store branch)

- Sonnet Apartments, a 2018 288-unit complex as part of the overhaul of the former Portner Place, which was a 48-unit HUD (Section 8) complex[35]

Retail

Retailers located on 14th Street near U Street include Room and Board, West Elm, Trader Joe's and Lululemon.

Public transportation

The Corridor is served by the U Street station of the Washington Metro (subway), with service on the Green Line and during rush hours on the Yellow Line as well. WMATA buses run along both U and 14th streets, and the DC Circulator Woodley Park-Adams Morgan-McPherson Square line stops at 14th and U. Capital Bikeshare and various scooter-sharing systems have stations/vehicles in the area.

Demographics of census tract 44

| Demographic | 2017 ACS est. | 2010 census | 2000 census | 1990 census | 1980 census |

| Total pop. | 5,385 (+18%) | 4,572 (+87%) | 2,450 (-17%) | 2,951 (-18%) | 3,598 |

| Children (under 18) | 6.9% | 6.8% | 27% | ||

| Seniors (65+) | 7.9% | 4.8% | 8.6% | ||

| Citizen (of over 18 pop.) | 90.3% | ||||

| Black non-Hispanic | 18.4% | 21.5% | 58% | 77% | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 67.1% | 60.8% | 22% | 8.7% | |

| Asian and Pac. Isl. (Hisp. + Non-Hisp.) | 4.9% | 6.8% | 1.7% | 1.6% | |

| Hispanic | 6.1% | 9.1% | 17% | 12% | |

| Two or more races incl. Hispanic | 4.4% | 2.7% | |||

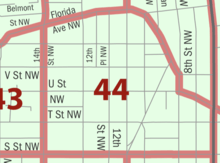

Census tract 44 is bounded by 14th, S, and 7th streets and Florida Av. NW, thus including the entire U Street Corridor plus four blocks east of 9th St. NW. This tract counted a population of 5,385 in the 2017 American Community Survey,[5] more than double the 1990 population, an increase reflecting among other things residents of new luxury complexes in which since 2010, 700 new residential units were added (see #Residential above). The official census count was 4,572 in 2010, an 87% increase from only 2,450 in 2000, thus reversing the trend of a decreasing population from 2,951 in 1990 and 3,598 in 1980.

6.8% were children in 2010, sharply down from 27% in 1990. Seniors also showed a decline at 4.8% in 2010, down from 8.6% in 1990. The foreign-born population was 18% in 2011–15, up from only 2.3% in 1980.[23]

The per capita income in 2017 was est. $110,175 ±$10,961, more than double the average in D.C. ($50,832 ±$645); the Median household income was est. $166,071, more than$166,071, more than double the D.C. average of $77,649.[5]

The racial change in the tract's population has been dramatic; black non-Hispanic population was 18% in 2017, down from 22% in 2010, and sharply down from 58% in 2000 and 77% in 1990; corresponding to an increase in the white non-Hispanic population (67% in 2017, 61% in 2010, 22% in 2000, 8.7% in 1990). The Hispanic population was 9.1% in 2010, down from 17% in 2000 and 12% in 1990, and the Asian/Pacific Islander population was 6.8% in 2010, up from 1.7% in 2000 and 1.6% in 1990.[23]

See also

- Mary Ann Shadd Cary House

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Northwest Quadrant, Washington, D.C.

References

- "District of Columbia - Inventory of Historic Sites" (PDF). District of Columbia: Office of Planning. Government of the District of Columbia. September 1, 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 17, 2009. Retrieved August 8, 2009.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Jones, Erica. "A Look Back at DC's 'Black Broadway'". NBC New York. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- "10 Things to See & Do On U Street". Washington.org. March 21, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- "Census profile: Census Tract 44, District of Columbia, DC". Census Reporter.

- Levey, Jane Freundel; Williams, Paul K. (2006). Midcity at the Crossroads: Shaw Heritage Trail. Cultural Tourism DC. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- "Building a Block of Prosperity in Shaw". March 20, 2000 – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- https://planning.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/op/publication/attachments/District%20Elements_Volume%20II_Chapter%2020_April%208%202011.pdf

- https://planning.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/op/publication/attachments/final_uptown_report.pdf_0.pdf

- Williams, Paul K. (2001). City within a City: Greater U Street Heritage Trail. Cultural Tourism DC. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- 1888 U.S. Geological Service maps

- "U Street/Shaw". culturaltourismdc.org. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Thomas, Briana (February 12, 2017). "The Forgotten History of U Street". Washingtonian. Archived from the original on April 4, 2018.

- Duke Ellington's Jazz Tour, Site Seeing Tours

- Wiltz, Teresa (March 5, 2006). "U Turn". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on April 4, 2018.

- Geiling, Natasha (May 31, 2014). "Grab a Drink, on the Sly, at One of D.C.'s Former Speakeasies". Smithsonian. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- Kaiser, Robert G. (April 22, 2004). "A City of Splendid Spaces, Great Events; 4 Landmarks Offer Washingtonians Gateways to a Capital Adventure". The Washington Post.

- "Historypin". Historypin. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Kaplan, Sarah (August 27, 2014). "Recording 'Black Broadway': A U Street oral history project aims to capture what once was". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015.

- Steve Inskeep (April 8, 2008). "U Street Corridor: Tracing a D.C. Neighborhood's Comeback from 1968". NPR. Archived from the original on April 4, 2018.

- Lusane, Clarence Pipe Dream Blues: Racism and the War on Drugs South End Press, Boston 1991, ISBN 0-89608-410-8

- Kreyling, Christine. "Something Old, Something New," Planning; August/September 2006, Vol. 72 Issue 8, p34-39, 6p. Retrieved April 4, 2007.

- "DC 2010 Tract Profile - Population - NeighborhoodInfo DC". www.neighborhoodinfodc.org. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- Hyra, Derek (June 12, 2017). "Selling a Black D.C. Neighborhood to White Millennials". Next City. Archived from the original on April 4, 2018.

- "2011 Great Places in America". American Planning Association.

- "2011 Great Places in America". U Street NW, Washington, D.C. American Planning Association. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012.

- "About Us – Ben's Chili Bowl". benschilibowl.com. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- African American Heritage Trail. Cultural Tourism DC. 2003. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- Smith, Kathryn S. (January 1, 1997). "Remembering U Street". Washington History. 9 (2): 28–53. JSTOR 40073294.

- "Music". The Washington Post.

- Jon Banister, "The difference a decade makes: images show rapid growth of 7 D.C. neighborhoods", Bisnow, July 17, 2018

- https://www.bizjournals.com/washington/news/2017/01/25/jbg-seeking-buyers-for-u-street-development-one.html

- "New apartments on D.C.'s U Street offer high-end appointments". Washington Post.

- https://www.bizjournals.com/washington/breaking_ground/2013/04/the-jbg-cos-sells-14th-street.html

- https://dc.urbanturf.com/pipeline/340/Sonnet

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to U Street Corridor, Washington, D.C.. |

- City within a City: Greater U Street Heritage Trail, DC Cultural Tours

- Black Broadway on U, a multimedia project about the area's African American history

- A historical guide to U Street provided by the National Trust for Historic Preservation

- Edelson, Harriet, "U Street corridor preserves its roots as it blossoms in new directions", Washington Post, 18 March 2016