Shaw (Washington, D.C.)

Shaw is a central neighborhood in the Northwest quadrant of Washington, D.C., United States. Shaw and the U Street Corridor historically have been the city's black social, cultural, and economic hub, witness to Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and numerous riots, marches, and protests that fought to achieve racial equality in Shaw and the entirety of America.[2] The District of Columbia has designated much of Shaw as the Shaw Historic District,[3] and Shaw also contains the smaller Blagden Alley-Naylor Court Historic District, listed on the National Register.

Shaw, Washington, D.C. | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood of Washington, D.C. | |

The Phillis Wheatley YWCA, built in 1920, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places | |

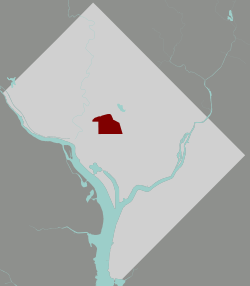

Shaw within the District of Columbia | |

| Country | United States |

| District | Washington, D.C. |

| Ward | Wards 1, 2, and 6 |

| Named for | Shaw School, named for Robert Gould Shaw |

| Government | |

| • Councilmember | Brianne Nadeau (Ward 1) Jack Evans (Ward 2) Charles Allen (Ward 6) |

| Area | |

| • Total | .73 sq mi (1.9 km2) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 17,639[1] |

| • Density | 24,163.0/sq mi (9,329.4/km2) |

Name

Until the 1960s, what is now Shaw was called Midcity. In 1966, planners used the enrollment boundary of Shaw Junior High School to define the Shaw School Urban Renewal Area covering what are now the Shaw, U Street Corridor and Logan Circle neighborhoods.[4] The school had been named after Robert Gould Shaw, who led the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, one of the first official African American units during the American Civil War.[5][6]

As the area diversified starting in the 1990s, neighborhoods in the north, west and east of what was considered Shaw during the urban renewal era became more frequently referred to by specific names, such as the U Street Corridor (a.k.a. Cardozo/Shaw), Logan Circle, Truxton Circle, and Randolph Square; for the remaining area (7th/9th street corridor north from Convention Center to U Street), "Shaw" remains the unique, unequivocal name.

Geography

Shaw is bounded by:[7]

- Florida Avenue NW and the U Street Corridor, Ledroit Park and Howard University on the north,

- M Street NW and Massachusetts Avenue NW, and Mount Vernon Square and Downtown Washington, D.C. on the south,

- First St. NW and Truxton Circle on the east, and

- 9th Street NW and the U Street and Logan Circle neighborhoods to the west.

Shaw consists of gridded streets lined mainly with small Victorian row houses, but also north of the convention center by urban-renewal-era low-rise apartment complexes and the late 2010s mixed-use development City Market at O.[8] The original commercial hub of the area prior to the redevelopment in the wake of the 1968 riots and Green Line Metrorail construction was along 7th and 9th streets NW, and especially 7th street is still lined by small businesses housed in rowhouse-sized buildings—though with trendy shops and restaurants rather than neighborhood-oriented businesses. Tucked away into the alleys here are former light industrial buildings that now constitute the Blagden Alley-Naylor Court Historic District, home to restaurants, cafés and other small businesses. The Shaw Main Streets association is centered along 7th and 9th Streets between K and W streets.[9]

History

Shaw emerged from freed slave encampments in the rural outskirts of Washington, D.C. It was originally called "Uptown", in an era when the city's boundary ended at "Boundary Street" (now Florida Avenue).[10]

The neighborhood thrived in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as the pre-Harlem, national center of U.S. black intellectual and cultural life. During this time, President Andrew Johnson signed Howard University's founding charter.[11] Furthermore, in 1925, Professor Alain LeRoy Locke advanced the idea of "The New Negro"[12] while Langston Hughes descended from LeDroit Park to hear the "sad songs" of 7th Street. Another famous Shaw native to emerge from this period—sometimes called the Harlem Renaissance—was Duke Ellington.[13]

Following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968, riots erupted in many D.C. neighborhoods, including Shaw, Columbia Heights, and the H Street, NE corridor.[13] The 1968 Washington, D.C. riots marked the beginning of a decline in population and development that condemned much of the inner city to a generation of economic decay.[14] After the riots, Shaw was left without electricity and with burnt down buildings. Crime and fear increased.[15] Succeeding the riots, Shaw civic leaders Walter Fauntroy and Watha T. Daniel led grassroots community renewal projects with the Model Inner City Community Organization (MICCO). MICCO used federal grant money to employ African American architects, engineers, and urban planners in inner-city Washington, D.C.[16]

Shaw is a residential neighborhood dominated by 19th-century Victorian row houses. The architecture of these houses, Shaw's central location, and the stability of D.C.'s housing market have transformed the neighborhood through gentrification.[17] Gentrification beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s generated new discussions between the inhabitants of the Shaw neighborhood and the Dupont Circle Conservancy organization. Preservation advocates in the Dupont Circle neighborhood began to propose the expansion of the neighborhood. The advocates were members of the Dupont Circle Conservancy, an organization predominantly led by European-American people. As a response to this proposal, the 14th and U Street Coalition, which called itself the representative of black interests and historical identity in neighboring Shaw, began protesting that the Dupont Circle preservationists were trying to occupy their neighborhood and its history.[18]

Discussions as such still have present day implications. Gentrification in the 2010s is transforming the neighborhood into an upscale retail hub.[19] But the mix of upscale newcomers and very poor, long-time residents have been linked to social implications that vary from cultural to political within the community. In Shaw, wealthy newcomers and lower class, long-term residents have shown differences in tastes, preferences, and values. Gentrification has also brought about a greater spectrum of political views in Shaw. Because the population has become more diversified, an influx of differing views, ideas, and outlooks has become more prominent.[20]

Infrastructure and landmarks

Public transportation

Shaw neighborhood is served by the Green and Yellow lines of the Washington Metro with stops at Shaw-Howard University Station, U Street Station and Mount Vernon Square Station. There is a bus service within Shaw, which has several routes that connects the area with the Waterfront and Silver Spring via 7th Street. Also, the G2 bus connects Georgetown University and Howard University. Freeway access allows cars to maneuver through the streets of Shaw.[21] Transit Score Methodology, which is a patented measure of how well a location is served by public transit on a scale from 0 to 100, measures the Shaw neighborhood with a score of 80. A score of 80 concludes that Shaw has "excellent transit", meaning transit is convenient for most trips. The White House, via public transit, is on average 10 minutes away from Shaw. Reagan National Airport, via public transit, is on average 28 minutes away from Shaw. Dulles International Airport, via cab, is on average 40 minutes away from Shaw.[22]

Cultural institutions

Shaw's neighborhood offers different cultural landmarks consisting of:

- Howard Theatre, owned by Abe Lichtman, a white owner of theaters that catered to African Americans, it was billed the "largest color theater in the World" in the 1970s. After restoration, it still hosts artists and performers in today's entertainment industry.[23]

- Dunbar Theater, currently known as the Southern Aid Society, holds nearly 350 seats and was a popular venue for live entertainment, including many jazz and blues artists as well as movies. Originally opening in the 1920s, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1968, shortly after closing in 1960.

- CityMarket at O (named " O Street Market" until 2008) is a Gothic Revival historic landmark, being one of the three public market buildings from the 19th century in DC; it won several awards for its design.

- The Shiloh Baptist Church, originally located in Fredericksburg (VA), plays an active part in helping, spiritually and economically, the Shaw's community. President Barack Obama and his family attended its Easter Sunday mass in 2011.[24]

- The Watha T. Daniel/Shaw Neighborhood Library is a three-level library of which design was renovated in 2010 and received several awards for its excellence; it was also named as one of the top buildings of 2010 by The Wall Street Journal.[25]

- The Walter E. Washington Convention Center, whose north portion is located in Shaw, has 703,000 square feet of exhibition space. It has hosted several official events including some hosted by President Barack Obama. It is also famous for its eco-friendly features. From 2017 to 2024, the WEWCC will be hosting Otakon.[26]

Parks and recreation

- Shaw Park, Shaw Dog Park, Cardozo Recreation Center

- Kennedy Recreation Center including a baseball field

- Bundy Field, Bundy Dog Park

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1950 | 34,208 | — | |

| 1960 | 25,749 | −24.7% | |

| 1970 | 19,994 | −22.4% | |

| 1980 | 15,901 | −20.5% | |

| 1990 | 15,044 | −5.4% | |

| 2000 | 14,997 | −0.3% | |

| 2010 | 17,639 | 17.6% | |

Shaw has grown dramatically since the mid-to-late 20th century, with a 2010 population of 17,639. In 1950, the area's population had reached over 34,000 people, around double its current level.[27] Like many neighborhoods throughout Washington, D.C., Shaw hit a population low point in the 1980s and 1990s, rebounding considerably at the turn of the 21st century.[27] The lack of investment and limited power in the area created a barrier in the neighborhood's development and urbanization during the early 1800s. Further growth was hindered by increasing racial tensions as more African-Americans settled in the region; by the 1850s, Washington, D.C. had the largest African-American population of any city in the United States. The increasing costs of housing also decreased the availability of affordable housing, generating further racial tensions citywide and neighborhood segregation.[28] One such neighborhood was Shaw, which continues to be populated by many African-Americans, but also Shaw is now experiencing an increase in prices. Newly constructed luxury apartment buildings include The Shay and Jefferson Marketplace. The current forecast for the price of housing expects a steady increase of about 2.5% over the few years, which could lead to further displacement among the black community and a phenomenon known as root shock.[29] According to the latest census of the Logan Circle/Shaw area, majority (71%) of residents is single, college-educated (67%) and has a median income of $84,875.[30]

The majority of residents in Shaw are between the ages of 22 and 39; they constitute 44.5% of the population. This is greater than the average District of Columbia percentage of 34.5% for this age group. Children between the ages of 0 to 17 make up 15.4% of the population. The percentages of genders within each age group is generally equal except for 85+ which has 94.4% female to only 5.6% male and 20-year-olds which is 84.9% female to 15.1% male.[31]

Little Ethiopia

Since the 1980s, Ethiopian-born business owners have been purchasing property in the neighbourhood of Shaw, specifically Thirteenth and Ninth Streets.[32] The area has since gained distinctive popularity in Washington even outside of the Ethiopian community. According to restaurant owner Tefera Zwedie: "I remember it was if I'm not mistaken somewhere between 2000, 2001 it was something big for us to see one non-Ethiopian coming to the restaurant. Now 95 percent of them are non-Ethiopian." The food has become a main attraction and reason for locals and tourists to commute to Shaw and experience the many local Ethiopian restaurants.This influx of Ethiopians has revitalized the area, prompting members of the Ethiopian American community to lobby the city government to officially designate the block as "Little Ethiopia". Although no legislation was proposed, Shaw residents have expressed opposition to the idea, concerned that such a designation would isolate that area from the historically African-American Shaw.[33]

Education

District of Columbia Public Schools – operates public schools.

District of Columbia Public Library – operates the Watha T. Daniel/Shaw Community Library.[34]

References

- Smith, Kathryn S. (1997-01-01). "Remembering U Street". Washington History. 9 (2): 28–53. JSTOR 40073294.

- "Shaw Historic District | op".

- Levey, Jane Freundel; Paul K. Williams (2006). Midcity at the Crossroads: Shaw Heritage Trail. Cultural Tourism DC. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "Shaw's Roots: From 'Heart Of Chocolate City' To 'Little United Nations'". WAMU.org. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- Wheeler, Linda (20 October 1983). "D.C. Neighborhood Names Rekindle History". Washington Post. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- https://planning.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/op/publication/attachments/shaw_nif_final_plan.pdf

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/where-we-live/wp/2017/05/24/new-luxury-apartments-rise-at-city-market-at-o-in-d-c-s-shaw

- "Shaw Main Streets – Who We Are". www.shawmainstreets.org. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- "D.C. zone unit loses its fight on apartment". The Washington Post. Jan 5, 1937.

- "Howard University: A Vital Place A S DOC YOUNG". Los Angeles Sentinel. Sep 6, 1990. p. A4.

- "Prof. Locke To Return To Howard Next Term". The Pittsburgh Courier (City ed.). 9 July 1927. p. 11.

- LaBarbara Bowman and Kenneth Bredemeier (April 4, 1983). "The Riots: Fifteen Years Later: Civic Leaders Cite Changes Since Riots". The Washington Post. p. D1.

- Robert L Asher and Robert G Kaiser (Dec 29, 1968). "Broken promises line riot area streets". The Washington Post, Times Herald.

- Claudia Levy and Leonard Downie Jr (Apr 5, 1970). "The Lights Are Still Out From Riots: First in a Series". The Washington Post, Times Herald. p. A1.

- "Oxford AASC: Home". www.oxfordaasc.com. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- Schwartzman, Paul (2006-02-23). "A Bittersweet Renaissance". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- Logan, Cameron (2012-01-01). "Beyond a Boundary: Washington's Historic Districts and Their Racial Contents". Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine. 41 (1): 57–68. JSTOR 43562421.

- "What a new shopping hub in D.C. shows us about the future of retail". Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- Hyra, Derek. "The Back-to-the-City Movement: Neighbourhood Redevelopment and Processes of Political and Cultural Displacement." Urban Studies 52 (August 2015): 1753–1775.

- whiteside@acm.org. "Where We Live: Shaw". We Love DC. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- "Shaw, Washington, D.C. Guide – Airbnb Neighborhoods". Airbnb. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- "Howard Theatre: A history". Greater Greater Washington. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- "Shiloh Baptist Church DC". www.shilohbaptist.org. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- "New Shaw (Watha T. Daniel) Library". District of Columbia Public Library. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- http://www.dcconvention.com/Venues/ConventionCenter.aspx

- "Government Census". Census.gov. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- "The History of Washington, DC". Washington.org. 2016-03-15. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- Inc., Zillow. "Shaw Washington DC Home Prices & Home Values | Zillow". Zillow. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- "Real Estate Overview for Logan Circle/ Shaw, Washington, DC - Trulia". www.trulia.com. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- "Age and Sex in Shaw, Washington, District of Columbia (Neighborhood)". Statistical Atlas. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- David, Nieves, Angel (2008-06-15). "Revaluing Places: Hidden Histories from the Margins". Places. 20 (1). ISSN 0731-0455.

- Showalter, Mistry. "Inside Washington D.C.'s 'Little Ethiopia'" CNN. Cable News Network, 22 Oct. 2010. Web. 12 Oct. 2016

- "Hours & Locations." District of Columbia Public Library. Retrieved on October 21, 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to U Street Corridor, Washington, D.C.. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shaw, Washington, D.C.. |