Comanche

The Comanche /kəˈmæntʃi/ (Comanche: Nʉmʉnʉʉ) are a Native-American nation from the Great Plains whose historic territory consisted of most of present-day northwestern Texas and adjacent areas in eastern New Mexico, southeastern Colorado, southwestern Kansas, western Oklahoma, and northern Chihuahua. Within the United States, the government federally recognizes the Comanche people as the Comanche Nation, headquartered in Lawton, Oklahoma.[1]

Flag of the Comanche[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| United States (Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico) | |

| Languages | |

| English, Comanche | |

| Religion | |

| Native American Church, Christianity, traditional tribal religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Shoshone and other Numic peoples |

The Comanche became the dominant tribe on the southern Great Plains in the 18th and 19th centuries. They are often characterized as "Lords of the Plains" and they presided over a large area called Comancheria, which came to include large portions of present-day Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Kansas.

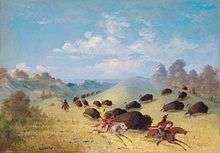

Comanche power depended on bison, horses, trading, and raiding. The Comanche hunted the bison of the Great Plains for food and skins; their adoption of the horse from Spanish colonists in New Mexico made them more mobile; they traded with the Spanish, French, Americans and neighboring Native-American peoples; and (most famously) they waged war on and raided European settlements as well as other Native Americans.[2] They took captives from weaker tribes during warfare, using them as slaves or selling them to the Spanish and (later) Mexican settlers. They also took thousands of captives from the Spanish, Mexican, and American settlers and incorporated them into Comanche society.[3]

Decimated by European diseases, warfare, and encroachment by Americans on Comancheria, most Comanches were forced into life on the reservation; a few however sought refuge with the Mescalero Apaches in New Mexico, or with the Kickapoos in Mexico. A number of them returned in the 1890s and early 1900s. In the 21st century, the Comanche Nation has 17,000 members, around 7,000 of whom reside in tribal jurisdictional areas around Lawton, Fort Sill, and the surrounding areas of southwestern Oklahoma.[4] The Comanche Homecoming Annual Dance takes place annually in Walters, Oklahoma, in mid-July.[5]

The Comanche language is a Numic language of the Uto-Aztecan family, sometimes classified as a Shoshoni dialect.[6] Only about 1% of Comanches speak this language today.[6][7]

The name "Comanche" comes from the Ute name for the people: kɨmantsi (enemy),.[8] The name Padouca, which before about 1740 was applied to Plains Apaches, was sometimes applied to the Comanche by French writers from the east.

Government

The Comanche Nation is headquartered in Lawton, Oklahoma. Their tribal jurisdictional area is located in Caddo, Comanche, Cotton, Grady, Jefferson, Kiowa, Stephens, and Tillman Counties. Membership of the tribe requires a 1/8 blood quantum (equivalent to one great-grandparent).[1]

Economic development

The tribe operates its own housing authority and issues tribal vehicle tags. They have their own Department of Higher Education, primarily awarding scholarships and financial aid for members' college educations. Additionally, they operate the Comanche Nation College in Lawton. They own 10 tribal smoke shops and four casinos.[1] The casinos are Comanche Nation Casino in Lawton; Comanche Red River Casino in Devol; Comanche Spur Casino, in Elgin; and Comanche Star Casino in Walters, Oklahoma.[9]

Cultural institutions

In 2002, the tribe founded the Comanche Nation College, a two-year tribal college in Lawton.[10] It has since closed.

Each July, Comanches from across the United States gather to celebrate their heritage and culture in Walters at the annual Comanche Homecoming powwow. The Comanche Nation Fair is held every September. The Comanche Little Ponies host two annual dances—one over New Year's and one in May.[11]

History

Formation

The Proto-Comanche movement to the Plains was part of the larger phenomenon known as the “Shoshonean Expansion” in which that language family spread across the Great Basin and across the mountains into Wyoming. The Kotsoteka (‘Buffalo Eaters’) were probably among the first. Other groups followed. Contact with the Shoshones of Wyoming was maintained until the 1830s when it was broken by the advancing Cheyennes and Arapahoes.

After the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, various Plains peoples acquired horses, but probably never had very many for quite some time. As late as 1725, Comanches were described as using large dogs rather than horses to carry their buffalo hide "campaign tents." [12]

The horse was a key element in the emergence of a distinctive Comanche culture. It was of such strategic importance that some scholars suggested that the Comanche broke away from the Shoshone and moved southward to search for additional sources of horses among the settlers of New Spain to the south (rather than search for new herds of buffalo.) The Comanche have the longest documented existence as horse-mounted Plains peoples; they had horses when the Cheyennes still lived in earth lodges.[13]

The Comanche supplied horses and mules to all comers. As early as 1795, Comanches were selling horses to Anglo-American traders [14] and by the mid-19th century, Comanche supplied horses were flowing into St. Louis via other Indian middlemen (Seminole, Osage, Shawnee).[15]

Their original migration took them to the southern Great Plains, into a sweep of territory extending from the Arkansas River to central Texas. The earliest references to them in the Spanish records date from 1706, when reports reached Santa Fe that Utes and Comanches were about to attack.[14] In the Comanche advance, the Apaches were driven off the Plains. By the end of the eighteenth century the struggle between Comanches and Apaches had assumed legendary proportions: in 1784, in recounting the history of the southern Plains, Texas governor Domingo Cabello recorded that some sixty years earlier (i.e., ca. 1724) the Apaches had been routed from the southern Plains in a nine-day battle at El Gran Cierra del Fierro ‘The Great Mountain of Iron’, somewhere northwest of Texas. There is, however, no other record, documentary or legendary, of such a fight.[12]

They were formidable opponents who developed strategies for using traditional weapons for fighting on horseback. Warfare was a major part of Comanche life. Comanche raids into Mexico traditionally took place during the full moon, when the Comanche could see to ride at night. This led to the term "Comanche Moon", during which the Comanche raided for horses, captives, and weapons.[16] The majority of Comanche raids into Mexico were in the state of Chihuahua and neighboring northern states.[17]

Divisions

Kavanagh has defined four levels of social-political integration in traditional pre-reservation Comanche society:[18]

- Patrilineal and patrilocal nuclear family

- Extended family group (nʉmʉnahkahni – "the people who live together in a household", no size limits, but kinship recognition was limited to relatives two generations above or three below)

- Residential local group or 'band', comprised one or more nʉmʉnahkahni, one of which formed its core. The band was the primary social unit of the Comanche. A typical band might number several hundred people. It was a family group, centered around a group of men, all of whom were relatives, sons, brothers or cousins. Since marriage with a known relative was forbidden, wives came from another group, and sisters left to join their husbands. The central man in that group was their grandfather, father, or uncle. He was called 'paraivo', 'chief'. After his death, one of the other men took his place; if none were available, the band members might drift apart to other groups where they might have relatives and/or establish new relations by marrying an existing member. There was no separate term for or status of 'peace chief' or 'war chief'; any man leading a war party was a 'war chief'.

- Division (sometimes called tribe, Spanish nación, rama – "branch", comprising several local groups linked by kinship, sodalities (political, medicine, and military) and common interest in hunting, gathering, war, peace, trade).

In contrast to the neighboring Cheyenne and Arapaho to the north, there was never a single Comanche political unit recognized by all Comanches. or "Nation." Rather the divisions, the most "tribe-like" units, acted independently, pursuing their own economic and political goals.

Many Anglo-American writers have used geographical terms to label Comanche, Eastern, Western; Northern, Middle, Southern. However, these terms generally do not correspond to the Native language terms.

Before the 1750s, the three Comanche divisions were: Yamparikas, Jupes, and Kotsotekas.

Over time, these divisions were altered in various ways, pimarily due to changes in political resources.[19] As noted above, the Kotsotekas were probably the first proto-Comanche group to separate from the Eastern Shoshones. In the 1750s and 1760s, a number of Kotsoteka bands split off and moved to the southeast; the western Kotsoteka lived in the region of the upper Arkansas, Canadian, and Red Rivers, and the Llano Estacado. The eastern Kotsotekas lived on the Edwards Plateau and the Texas plains of the upper Brazos and Colorado Rivers, and east to the Cross Timbers. They were probably the ancestors of the Penateka, (Penatʉka Nʉʉ)[20]

The name Jupes vanished from history in the early 19th century, probably merging into the other divisions. Many Yamparikas moved southeast, joining the eastern Comanche and becoming known as the Tenewa. Many Kiowa and Plains Apache (or Naishan) moved to northern Comancheria and became closely associated with the Yamparika.

In the mid 19th century, other divisions arose, such as the Nokonis ('wanderers', literally 'go someplace and return'), and the Kwahadi ('Antelopes').

The northernmost Comanche division was the Yamparikas (Yaparʉhka or Yapai Nʉʉ — ‘(Yap)Root-Eaters’). As the last band to move onto the Plains, they retained much of their Shoshone tradition.

There has been, and continues to be, much confusion in the presentation of Comanche group names. Groups on all levels of organization, families, nʉmʉnahkahni, bands, and divisions, were given names, but many 'band lists' do not distinguish these levels. In addition, there could be alternate names and nicknames. The spelling differences between Spanish and English add to the confusion.

Some of the Comanche group names

- Yaparʉhka or Yamparika (also Yapai Nʉʉ — ‘(Yap)Root-Eaters’; One of its local groups may have been called Widyʉ Nʉʉ / Widyʉ / Widyʉ Yapa — ‘Awl People’; after the death of a man named 'Awl' they changed their name to Tʉtsahkʉnanʉʉ or Ditsahkanah — ‘Sewing People’. [Titchahkaynah]

Other Yapai local groups included:

- Ketahtoh or Ketatore (‘Don't Wear Shoes’, also called Napwat Tʉ — ‘Wearing No Shoes’)

- Motso (′Bearded Ones′, derived from motso — ‘Beard’)

- Pibianigwai (‘Loud Talkers’, ‘Loud Askers’)

- Sʉhmʉhtʉhka (‘Eat Everything’)

- Wahkoh (‘Shell Ornament’)

- Waw'ai or Wohoi (also Waaih – ′Lots of Maggots on the Penis′, also called Nahmahe'enah – ′Somehow being (sexual) together′, ′to have sex′, called by other groups, because they preferred to marry endogamy and chose their partners out of their own local group, this was viewed critically by other Comanche people)

- Hʉpenʉʉ or Jupe (‘Timber People’ because they lived in more wooded areas in the Central Plains north of the Arkansas River. Also spelled Hois.

- Kʉhtsʉtʉʉka or Kotsoteka (‘Buffalo-Eaters’, spelled in Spanish as Cuchanec)

- Kwaarʉnʉʉ or Kwahadi/Quohada (Kwahare — ‘Antelope-Eaters’; nicknamed Kwahihʉʉki — ‘Sunshades on Their Backs’, because they lived on desert plains of the Llano Estacado in eastern New Mexico, westernmost Comanche Band). One of their local groups was nicknamed Parʉhʉya ('Elk', literally‘Water Horse’).

- Nokoninʉʉ or Nokoni (‘Movers’, ‘Returners’); allegedly, after the death of chief Peta Nocona they called themselves Noyʉhkanʉʉ — ‘Not Staying in one place’, and/orTʉtsʉ Noyʉkanʉʉ / Detsanayʉka — ‘Bad Campers’, ‘Poor Wanderer’.

- Tahnahwah or Tenawa (also Tenahwit — ‘Those Who Live Downstream’,

- Tanimʉʉ or Tanima (also called Dahaʉi or Tevawish — ‘Liver-Eaters’,

- Penatʉka Nʉʉ or Penateka (other variants: Pihnaatʉka, Penanʉʉ — ‘Honey-Eaters’;

Some names given by others include:

- WahaToya (literally 'Two Mountains'); (given as Foothills in Cloud People - those who live near Walsenburg, CO)<Whatley: Jemez-Comanche-Kiowa repatriation, 1993-1999>

- Toyanʉmʉnʉ (′Foothills People′ - those who lived near Las Vegas, NM) <Whatley: Jemez-Comanche-Kiowa repatriation, 1993-1999>

Unassignable names include:

- Tayʉʉwit / Teyʉwit (‘Hospitable Ones’)

- Kʉvahrahtpaht (‘Steep Climbers’)

- Taykahpwai / Tekapwai (‘No Meat’)

- Pagatsʉ (Pa'káh'tsa — ‘Head of the Stream’, also called Pahnaixte — ‘Those Who Live Upstream’)

- Mʉtsahne or Motsai (‘Undercut Bank’)

Old Shoshone names

- Pekwi Tʉhka (‘Fish-Eaters’)

- Pohoi / Pohoee (‘Wild Sage’)

Other names, which may or may not refer to Comanche groups include:

- Hani Nʉmʉ (Hai'ne'na'ʉne — ‘Corn Eating People’) Wichitas.

- It'chit'a'bʉd'ah (Utsu'itʉ — ‘Cold People’, i.e. ‘Northern People’, probably another name for the Yaparʉhka or one of their local groups - because they lived to the north)

- Itehtah'o (‘Burnt Meat’, nicknamed by other Comanche, because they threw their surplus of meat out in the spring, where it dried and became black, looking like burnt meat)

- Naʉ'niem (No'na'ʉm — ‘Ridge People’

Modern Local Groups

- Ohnonʉʉ (also Ohnʉnʉnʉʉ or Onahʉnʉnʉʉ, 'Salt People' or 'Salt Creek people'] live in Caddo County in the vicinity of Cyril, Oklahoma; mostly descendants of the Nokoni Pianavowit.

- Wianʉʉ (Wianʉ, Wia'ne — ‘Hill Wearing Away’, live east of Walters, Oklahoma, descendants of Waysee.

Comanche wars

The Comanche fought a number of conflicts against Spanish and later Mexican and American armies. These were both expeditionary, as with the raids into Mexico, and defensive in nature. The Comanche were noted for being fierce warriors who fought vigorously to defend their homeland of Comancheria. However, the massive population of the settlers from the east and the diseases they brought with them led to mounting pressure and subsequent decline of the Comanche power and the cessation of their major presence in the southern Great Plains.

Relationship with settlers

The Comanche maintained an ambiguous relationship with Europeans and later settlers attempting to colonize their territory. The Comanche were valued as trading partners since 1786 via the Comancheros of New Mexico, but were feared for their raids against settlers in Texas.[21][22][23][24] Similarly, they were, at one time or another, at war with virtually every other Native American group living on the South Plains,[25][26] leaving opportunities for political maneuvering by European colonial powers and the United States. At one point, Sam Houston, president of the newly created Republic of Texas, almost succeeded in reaching a peace treaty with the Comanche in the 1844 Treaty of Tehuacana Creek. His efforts were thwarted in 1845 when the Texas legislature refused to create an official boundary between Texas and the Comancheria.

While the Comanche managed to maintain their independence and increase their territory, by the mid-19th century, they faced annihilation because of a wave of epidemics due to Eurasian diseases to which they had no immunity, such as smallpox and measles. Outbreaks of smallpox (1817, 1848) and cholera (1849)[27] took a major toll on the Comanche, whose population dropped from an estimated 20,000 in midcentury to just a few thousand by the 1870s.

The US began efforts in the late 1860s to move the Comanche into reservations, with the Treaty of Medicine Lodge (1867), which offered churches, schools, and annuities in return for a vast tract of land totaling over 60,000 square miles (160,000 km2). The government promised to stop the buffalo hunters, who were decimating the great herds of the Plains, provided that the Comanche, along with the Apaches, Kiowas, Cheyenne, and Arapahos, move to a reservation totaling less than 5,000 square miles (13,000 km2) of land. However, the government did not prevent the slaughtering of the herds. The Comanche under Quenatosavit White Eagle (later called Isa-tai "Coyote's Vagina") retaliated by attacking a group of hunters in the Texas Panhandle in the Second Battle of Adobe Walls (1874). The attack was a disaster for the Comanche, and the US army was called in during the Red River War to drive the remaining Comanche in the area into the reservation, culminating in the Battle of Palo Duro Canyon. Within just 10 years, the buffalo were on the verge of extinction, effectively ending the Comanche way of life as hunters. In May 1875, the last free band of Comanches, led by the Quahada warrior Quanah Parker, surrendered and moved to the Fort Sill reservation in Oklahoma. The last independent Kiowa and Kiowa Apache had also surrendered.

The 1890 Census showed 1,598 Comanche at the Fort Sill reservation, which they shared with 1,140 Kiowa and 326 Kiowa Apache.[28]

Cherokee Commission

The Agreement with the Comanche, Kiowa and Apache signed with the Cherokee Commission October 6–21, 1892,[29] further reduced their reservation to 480,000 acres (1,900 km2) at a cost of $1.25 per acre ($308.88/km2), with an allotment of 160 acres (0.65 km2) per person per tribe to be held in trust. New allotments were made in 1906 to all children born after the agreement, and the remaining land was opened to white settlement. With this new arrangement, the era of the Comanche reservation came to an abrupt end.

Meusebach–Comanche treaty

The Peneteka band agreed to a peace treaty with the German Immigration Company under John O. Meusebach. This treaty was not affiliated with any level of government. Meusebach brokered the treaty to settle the lands on the Fisher-Miller Land Grant, from which were formed the 10 counties of Concho, Kimble, Llano, Mason, McCulloch, Menard, Schleicher, San Saba, Sutton, and Tom Green.[30]

In contrast to many treaties of its day, this treaty was very brief and simple, with all parties agreeing to a mutual cooperation and a sharing of the land. The treaty was agreed to at a meeting in San Saba County,[31] and signed by all parties on May 9, 1847 in Fredericksburg, Texas. The treaty was very specifically between the Peneteka band and the German Immigration Company. No other band or tribe was involved. The German Immigration Company was dissolved by Meusebach himself shortly after it had served its purpose. By 1875, the Comanches had been relocated to reservations.[32]

Five years later, artist Friedrich Richard Petri and his family moved to the settlement of Pedernales, near Fredericksburg. Petri's sketches and watercolors gave witness to the friendly relationships between the Germans and various local Native American tribes.[33]

Fort Martin Scott treaty

In 1850, another treaty was signed in San Saba, between the United States government and a number of local tribes, among which were the Comanches. This treaty was named for the nearest military fort, which was Fort Martin Scott. The treaty was never officially ratified by any level of government and was binding only on the part of the Native Americans.[34][35]

Captive Herman Lehmann

One of the most famous captives in Texas was a German boy named Herman Lehmann. He had been kidnapped by the Apaches, only to escape and be rescued by the Comanches. Lehmann became the adoptive son of Quanah Parker. On August 26, 1901, Quanah Parker provided a legal affidavit verifying Lehman's life as his adopted son 1877–1878. On May 29, 1908, the United States Congress authorized the United States Secretary of the Interior to allot Lehmann, as an adopted member of the Comanche nation, 160 acres of Oklahoma land, near Grandfield.[36]

Recent history

Entering the Western economy was a challenge for the Comanche in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many tribal members were defrauded of whatever remained of their land and possessions. Appointed paramount chief by the United States government, Chief Quanah Parker campaigned vigorously for better deals for his people, meeting with Washington politicians frequently; and helped manage land for the tribe. Parker became wealthy as a cattleman. Parker also campaigned for the Comanches' permission to practice the Native American Church religious rites, such as the usage of peyote, which was condemned by European Americans.[37]

Before the first Oklahoma legislature, Quanah testified:

I do not think this legislature should interfere with a man's religion, also these people should be allowed to retain this health restorer. These healthy gentleman before you use peyote and those that do not use it are not so healthy.[38]

During World War II, many Comanche left the traditional tribal lands in Oklahoma to seek jobs and more opportunities in the cities of California and the Southwest. About half of the Comanche population still lives in Oklahoma, centered on the town of Lawton.

Recently, an 80-minute 1920 silent film was "rediscovered", titled The Daughter of Dawn. It features a cast of more than 300 Comanche and Kiowa.[39]

Culture

Childbirth

If a woman went into labor while the band was in camp, she was moved to a tipi, or a brush lodge if it was summer. One or more of the older women assisted as midwives. Men were not allowed inside the tipi during or immediately after the delivery.[40]

First, the midwives softened the earthen floor of the tipi and dug two holes. One of the holes was for heating water and the other for the afterbirth. One or two stakes were driven into the ground near the expectant mother's bedding for her to grip during the pain of labor. After the birth, the midwives hung the umbilical cord on a hackberry tree. The people believed that if the umbilical cord was not disturbed before it rotted, the baby would live a long and prosperous life.[41]

The newborn was swaddled and remained with its mother in the tipi for a few days. The baby was placed in a cradleboard, and the mother went back to work. She could easily carry the cradleboard on her back, or prop it against a tree where the baby could watch her while she collected seeds or roots. Cradleboards consisted of a flat board to which a basket was attached. The latter was made from rawhide straps, or a leather sheath that laced up the front. With soft, dry moss as a diaper, the young one was safely tucked into the leather pocket. During cold weather, the baby was wrapped in blankets, and then placed in the cradleboard. The baby remained in the cradleboard for about ten months; then it was allowed to crawl around.[42]

Both girls and boys were welcomed into the band, but boys were favored. If the baby was a boy, one of the midwives informed the father or grandfather, "It's your close friend". Families might paint a flap on the tipi to tell the rest of the tribe that they had been strengthened with another warrior. Sometimes a man named his child, but mostly the father asked a medicine man (or another man of distinction) to do so. He did this in the hope of his child living a long and productive life. During the public naming ceremony, the medicine man lit his pipe and offered smoke to the heavens, earth, and each of the four directions. He prayed that the child would remain happy and healthy. He then lifted the child to symbolize its growing up and announced the child's name four times. He held the child a little higher each time he said the name. It was believed that the child's name foretold its future; even a weak or sick child could grow up to be a great warrior, hunter, and raider if given a name suggesting courage and strength.[42] Boys were often named after their grandfather, uncle, or other relative. Girls were usually named after one of their father's relatives, but the name was selected by the mother. As children grew up they also acquired nicknames at different points in their lives, to express some aspect of their lives.[43]

Children

The Comanche looked on their children as their most precious gift. Children were rarely punished.[44] Sometimes, though, an older sister or other relative was called upon to discipline a child, or the parents arranged for a boogey man to scare the child. Occasionally, old people donned sheets and frightened disobedient boys and girls. Children were also told about Big Maneater Owl (Pia Mupitsi), who lived in a cave on the south side of the Wichita Mountains and ate bad children at night.[45]

Children learned from example, by observing and listening to their parents and others in the band. As soon as she was old enough to walk, a girl followed her mother about the camp and played at the daily tasks of cooking and making clothing. She was also very close to her mother's sisters, who were called not aunt but pia, meaning mother. She was given a little deerskin doll, which she took with her everywhere. She learned to make all the clothing for the doll.[46]

A boy identified not only with his father but with his father's family, as well as with the bravest warriors in the band. He learned to ride a horse before he could walk. By the time he was four or five, he was expected to be able to skillfully handle a horse. When he was five or six, he was given a small bow and arrows. Often, a boy was taught to ride and shoot by his grandfather, since his father and other warriors were on raids and hunts. His grandfather also taught him about his own boyhood and the history and legends of the Comanche.[47]

As the boy grew older, he joined the other boys to hunt birds. He eventually ranged farther from camp looking for better game to kill. Encouraged to be skillful hunters, boys learned the signs of the prairie as they learned to patiently and quietly stalk game. They became more self-reliant, yet, by playing together as a group, also formed the strong bonds and cooperative spirit that they would need when they hunted and raided.[47]

Boys were highly respected because they would become warriors and might die young in battle. As he approached manhood, a boy went on his first buffalo hunt. If he made a kill, his father honored him with a feast. Only after he had proven himself on a buffalo hunt was a young man allowed to go to war.[47]

When he was ready to become a warrior, at about age fifteen or sixteen, a young man first "made his medicine" by going on a vision quest (a rite of passage). Following this quest, his father gave the young man a good horse to ride into battle and another mount for the trail. If he had proved himself as a warrior, a Give Away Dance might be held in his honor. As drummers faced east, the honored boy and other young men danced. His parents, along with his other relatives and the people in the band, threw presents at his feet – especially blankets and horses symbolized by sticks. Anyone might snatch one of the gifts for themselves, although those with many possessions refrained; they did not want to appear greedy. People often gave away all their belongings during these dances, providing for others in the band, but leaving themselves with nothing.[47]

Girls learned to gather healthy berries, nuts, and roots. They carried water and collected wood, and when about twelve years old learned to cook meals, make tipis, sew clothing, prepare hides, and perform other tasks essential to becoming a wife and mother. They were then considered ready to be married.[46]

Death

During the 19th century, the traditional Comanche burial custom was to wrap the deceased's body in a blanket and place it on a horse, behind a rider, who would then ride in search of an appropriate burial place, such as a secure cave. After entombment, the rider covered the body with stones and returned to camp, where the mourners burned all the deceased's possessions. The primary mourner slashed his arms to express his grief. The Quahada band followed this custom longer than other bands and buried their relatives in the Wichita Mountains. Christian missionaries persuaded Comanche people to bury their dead in coffins in graveyards,[48] which is the practice today.

Transportation and habitation

When they lived with the Shoshone, the Comanche mainly used dog-drawn travois for transportation. Later, they acquired horses from other tribes, such as the Pueblo, and from the Spaniards. Since horses are faster, easier to control and able to carry more, this helped with their hunting and warfare and made moving camp easier. Larger dwellings were made due to the ability to pull and carry more belongings. Being herbivores, horses were also easier to feed than dogs, since meat was a valuable resource.[49] The horse was of the utmost value to the Comanche. A Comanche man's wealth was measured by the size of his horse herd. Horses were prime targets to steal during raids; often raids were conducted specifically to capture horses. Often horse herds numbering in the hundreds were stolen by Comanche during raids against other Indian nations, Spanish, Mexicans, and later from the ranches of Texans. Horses were used for warfare with the Comanche being considered to be among the finest light cavalry and mounted warriors in history.[50]

The Comanche sheathed their tipis with a covering made of buffalo hides sewn together. To prepare the buffalo hides, women first spread them on the ground, then scraped away the fat and flesh with blades made from bones or antlers, and left them in the sun. When the hides were dry, they scraped off the thick hair, and then soaked them in water. After several days, they vigorously rubbed the hides in a mixture of animal fat, brains, and liver to soften the hides. The hides were made even more supple by further rinsing and working back and forth over a rawhide thong. Finally, they were smoked over a fire, which gave the hides a light tan color. To finish the tipi covering, women laid the tanned hides side by side and stitched them together. As many as 22 hides could be used, but 14 was the average. When finished, the hide covering was tied to a pole and raised, wrapped around the cone-shaped frame, and pinned together with pencil-sized wooden skewers. Two wing-shaped flaps at the top of the tipi were turned back to make an opening, which could be adjusted to keep out the moisture and held pockets of insulating air. With a fire pit in the center of the earthen floor, the tipis stayed warm in the winter. In the summer, the bottom edges of the tipis could be rolled up to let cool breezes in. Cooking was done outside during the hot weather. Tipis were very practical homes for itinerant people. Working together, women could quickly set them up or take them down. An entire Comanche band could be packed and chasing a buffalo herd within about 20 minutes. The Comanche women were the ones who did the most work with food processing and preparation.[51]

Food

The Comanche were initially hunter-gatherers. When they lived in the Rocky Mountains, during their migration to the Great Plains, both men and women shared the responsibility of gathering and providing food. When the Comanche reached the plains, hunting came to predominate. Hunting was considered a male activity and was a principal source of prestige. For meat, the Comanche hunted buffalo, elk, black bear, pronghorn, and deer. When game was scarce, the men hunted wild mustangs, sometimes eating their own ponies. In later years the Comanche raided Texas ranches and stole longhorn cattle. They did not eat fish or fowl, unless starving, when they would eat virtually any creature they could catch, including armadillos, skunks, rats, lizards, frogs, and grasshoppers. Buffalo meat and other game was prepared and cooked by the women. The women also gathered wild fruits, seeds, nuts, berries, roots, and tubers — including plums, grapes, juniper berries, persimmons, mulberries, acorns, pecans, wild onions, radishes, and the fruit of the prickly pear cactus. The Comanche also acquired maize, dried pumpkin, and tobacco through trade and raids. Most meats were roasted over a fire or boiled. To boil fresh or dried meat and vegetables, women dug a pit in the ground, which they lined with animal skins or buffalo stomach and filled with water to make a kind of cooking pot. They placed heated stones in the water until it boiled and had cooked their stew. After they came into contact with the Spanish, the Comanche traded for copper pots and iron kettles, which made cooking easier.

Women used berries and nuts, as well as honey and tallow, to flavor buffalo meat. They stored the tallow in intestine casings or rawhide pouches called oyóotû¿. They especially liked to make a sweet mush of buffalo marrow mixed with crushed mesquite beans.

The Comanches sometimes ate raw meat, especially raw liver flavored with gall. They also drank the milk from the slashed udders of buffalo, deer, and elk.[52] Among their delicacies was the curdled milk from the stomachs of suckling buffalo calves. They also enjoyed buffalo tripe, or stomachs.

Comanche people generally had a light meal in the morning and a large evening meal. During the day they ate whenever they were hungry or when it was convenient. Like other Plains Indians, the Comanche were very hospitable people. They prepared meals whenever a visitor arrived in camp, which led to outsiders' belief that the Comanches ate at all hours of the day or night. Before calling a public event, the chief took a morsel of food, held it to the sky, and then buried it as a peace offering to the Great Spirit. Many families offered thanks as they sat down to eat their meals in their tipis.

Comanche children ate pemmican, but this was primarily a tasty, high-energy food reserved for war parties. Carried in a parfleche pouch, pemmican was eaten only when the men did not have time to hunt. Similarly, in camp, people ate pemmican only when other food was scarce. Traders ate pemmican sliced and dipped in honey, which they called Indian bread.

Clothing

Comanche clothing was simple and easy to wear. Men wore a leather belt with a breechcloth — a long piece of buckskin that was brought up between the legs and looped over and under the belt at the front and back, and loose-fitting deerskin leggings. Moccasins had soles made from thick, tough buffalo hide with soft deerskin uppers. The Comanche men wore nothing on the upper body except in the winter, when they wore warm, heavy robes made from buffalo hides (or occasionally, bear, wolf, or coyote skins) with knee-length buffalo-hide boots. Young boys usually went without clothes except in cold weather. When they reached the age of eight or nine, they began to wear the clothing of a Comanche adult. In the 19th century, men used woven cloth to replace the buckskin breechcloths, and the men began wearing loose-fitting buckskin shirts. The women decorated their shirts, leggings and moccasins with fringes made of deer-skin, animal fur, and human hair. They also decorated their shirts and leggings with patterns and shapes formed with beads and scraps of material. Comanche women wore long deerskin dresses. The dresses had a flared skirt and wide, long sleeves, and were trimmed with buckskin fringes along the sleeves and hem. Beads and pieces of metal were attached in geometric patterns. Comanche women wore buckskin moccasins with buffalo soles. In the winter they, too, wore warm buffalo robes and tall, fur-lined buffalo-hide boots. Unlike the boys, young girls did not go without clothes. As soon as they were able to walk, they were dressed in breechcloths. By the age of twelve or thirteen, they adopted the clothes of Comanche women.[53]

Hair and headgear

Comanche people took pride in their hair, which was worn long and rarely cut. They arranged their hair with porcupine quill brushes, greased it and parted it in the center from the forehead to the back of the neck. They painted the scalp along the parting with yellow, red, or white clay (or other colors). They wore their hair in two long braids tied with leather thongs or colored cloth, and sometimes wrapped with beaver fur. They also braided a strand of hair from the top of their head. This slender braid, called a scalp lock, was decorated with colored scraps of cloth and beads, and a single feather. Comanche men rarely wore anything on their heads. Only after they moved onto a reservation late in the 19th century did Comanche men begin to wear the typical Plains headdress. If the winter was severely cold, they might wear a brimless, woolly buffalo hide hat. When they went to war, some warriors wore a headdress made from a buffalo's scalp. Warriors cut away most of the hide and flesh from a buffalo head, leaving only a portion of the woolly hair and the horns. This type of woolly, horned buffalo hat was worn only by the Comanche. Comanche women did not let their hair grow as long as the men did. Young women might wear their hair long and braided, but women parted their hair in the middle and kept it short. Like the men, they painted their scalp along the parting with bright paint.[54]

Body decoration

Comanche men usually had pierced ears with hanging earrings made from pieces of shell or loops of brass or silver wire. A female relative would pierce the outer edge of the ear with six or eight holes. The men also tattooed their face, arms, and chest with geometric designs, and painted their face and body. Traditionally they used paints made from berry juice and the colored clays of the Comancheria. Later, traders supplied them with vermilion (red pigment) and bright grease paints. Comanche men also wore bands of leather and strips of metal on their arms. Except for black, which was the color for war, there was no standard color or pattern for face and body painting: it was a matter of individual preference. For example, one Comanche might paint one side of his face white and the other side red; another might paint one side of his body green and the other side with green and black stripes. One Comanche might always paint himself in a particular way, while another might change the colors and designs when so inclined. Some designs had special meaning to the individual, and special colors and designs might have been revealed in a dream. Comanche women might also tattoo their face or arms. They were fond of painting their bodies and were free to paint themselves however they pleased. A popular pattern among the women was to paint the insides of their ears a bright red and paint great orange and red circles on their cheeks. They usually painted red and yellow around their lips.[55]

Arts and crafts

Because of their frequent traveling, Comanche Indians had to make sure that their household goods and other possessions were unbreakable. They did not use pottery that could easily be broken on long journeys. Basketry, weaving, wood carving, and metal working were also unknown among the Comanches. Instead, they depended upon the buffalo for most of their tools, household goods, and weapons. They made nearly 200 different articles from the horns, hide, and bones of the buffalo.

Removing the lining of the inner stomach, women made the paunch into a water bag. The lining was stretched over four sticks and then filled with water to make a pot for cooking soups and stews. With wood scarce on the plains, women relied on buffalo chips (dried dung) to fuel the fires that cooked meals and warmed the people through long winters.[56]

Stiff rawhide was fashioned into saddles, stirrups and cinches, knife cases, buckets, and moccasin soles. Rawhide was also made into rattles and drums. Strips of rawhide were twisted into sturdy ropes. Scraped to resemble white parchment, rawhide skins were folded to make parfleches in which food, clothing, and other personal belongings were kept. Women also tanned hides to make soft and supple buckskin, which was used for tipi covers, warm robes, blankets, cloths, and moccasins. They also relied upon buckskin for bedding, cradles, dolls, bags, pouches, quivers, and gun cases.

Sinew was used for bowstrings and sewing thread. Hooves were turned into glue and rattles. The horns were shaped into cups, spoons, and ladles, while the tail made a good whip, a fly-swatter, or a decoration for the tipi. Men made tools, scrapers, and needles from the bones, as well as a kind of pipe, and fashioned toys for their children. As warriors, however, men concentrated on making bows and arrows, lances, and shields. The thick neck skin of an old bull was ideal for war shields that deflected arrows as well as bullets. Since they spent most of each day on horseback, they also fashioned leather into saddles, stirrups, and other equipment for their mounts. Buffalo hair was used to fill saddle pads and was also used in rope and halters.[57]

Language

The language spoken by the Comanche people, Comanche (Numu tekwapu), is a Numic language of the Uto-Aztecan language group. It is closely related to the language of the Shoshone, from which the Comanche diverged around 1700. The two languages remain closely related, but a few low-level sound changes inhibit mutual intelligibility. The earliest records of Comanche from 1786 clearly show a dialect of Shoshone, but by the beginning of the 20th century, these sound changes had modified the way Comanche sounded in subtle, but profound, ways.[58][59] Although efforts are now being made to ensure survival of the language, most of its speakers are elderly, and less than one percent of the Comanches can speak it.

In the late 19th century, many Comanche children were placed in boarding schools with children from different tribes. The children were taught English and discouraged from speaking their native language. Anecdotally, enforcement of speaking English was severe.

Quanah Parker learned and spoke English and was adamant that his own children do the same. The second generation then grew up speaking English, because it was believed that it was better for them not to know Comanche.[60]

During World War II, a group of 17 young men, referred to as "The Comanche Code Talkers", were trained and used by the U.S. Army to send messages conveying sensitive information that could not be deciphered by the Germans.[61][62]

Notable Comanches

- Spirit Talker (Mukwooru) (c. 1780-1840), Penateka chief and medicine man

- Old Owl (Mupitsukupʉ) (late 1780s–1849), Penateka chief

- Amorous Man (Pahayoko) (late 1780s–c. 1860), Penateka chief

- Ten Bears (Pawʉʉrasʉmʉnunʉ) (c. 1790–1872), chief of the Ketahto and later of the Yamparika band

- Santa Anna (c. 1800-c. 1849), war chief of the Penateka Band

- Buffalo Hump (Potsʉnakwahipʉ) (c. 1800-c. 1865/1870), war chief and later head chief of the Penateka Band

- Iron Jacket (Puhihwikwasu'u) (c. 1790-1858), war chief and later head chief of the Quahadi band; father of Peta Nocona

- Horseback (Tʉhʉyakwahipʉ) (c. 1805/1810-c. 1888), chief of the Nokoni band

- Tosawi (White Knife) (c. 1805/1810-c. 1878/1880), chief of the Penateka band

- Peta Nocona (Lone Wanderer) (c. 1820-c. 1864), chief of the Nokoni division; father of Quanah Parker

- Piaru-ekaruhkapu (Big Red Meat) (c. 1820/1825-1875), Nokoni chief

- Isatai (c. 1840–c. 1890), warrior and medicine man of the Quahadi band

- Diane O'Leary (1939–2013), artist, nurse

- Quanah Parker (c. 1845–1911), Quahadi chief, a founder of Native American Church, and successful rancher

- White Parker (1887–1956), son of Quanah Parker and Methodist missionary

- Gil Birmingham (born 1953), actor, Into the West

- Blackbear Bosin (1921–1980), Kiowa-Comanche sculptor and painter

- Charles Chibitty (1921–2005), World War II Comanche code talker

- Marie C. Cox (1920-2005), founder of the North American Indian Women's Association and foster care reform advocate

- LaDonna Harris (born 1931), political activist and founder of Americans for Indian Opportunity

- Lotsee Patterson (born 1931), librarian, educator, and founder of the American Indian Library Association

- Tom Mauchahty-Ware (1949-2015), Kiowa-Comanche musician

- Sonny Nevaquaya (d. 2019), Native American flute-player

- Sanapia (1895–1984), medicine woman

- Paul Chaat Smith, author, curator

- George "Comanche Boy" Tahdooahnippah (born 1978), professional boxer and NABC super middleweight champion

- Rudy Youngblood (born 1982), actor, starred in Apocalypto

- Jesse Ed Davis (1944-1988), guitarist and recording artist

See also

References

- "2011 Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Directory" (PDF). Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 12, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- Fowles, Severin, Arterberry, Lindsay Montgomery, Atherton, Heather (2017), "Comanche New Mexico: The Eighteenth Century," in New Mexico and the Pimeria Alta, Boulder: University Press of Colorado, pp. 158-160. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- Marez, Curtis (June 2001). "Signifying Spain, Becoming Comanche, Making Mexicans: Indian Captivity and the History of Chicana/o Popular Performance". American Quarterly. 53 (2): 267–307. doi:10.1353/aq.2001.0018.

- "The Official Site of the Comanche Nation ~ Lawton, Oklahoma". Comanchenation.com. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- "The Homecoming Dance". Comanche Nation official website. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- "Comanche – American Indians". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29.

- "Comanche Indians". TSHA Handbook of Texas. Archived from the original on 2019-07-13. Retrieved 2017-12-09.

- Bright, William, ed. (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press.

- "Oklahoma Indian Casinos." 500 Nations. Retrieved 2 Jan 2011.

- Comanche Nation College. 2009 (16 February 2009)

- Comanche Nation Tourism Center. Archived 2008-11-04 at the Wayback Machine Comanche Nation. (16 February 2009)

- Kavanagh 66

- Kavanagh 7

- Kavanagh 63

- Kavanagh 380

- Wallace and Hoebel

- Kavanagh (1996)

- Kavanagh 41–53

- Kavanagh 478

- "Penateka Comanches ~ Marker Number: 16257". Texas Historic Sites Atlas. Camp Verde, Texas: Texas Historical Commission. 2009.

- Plummer, R., Narrative of the Capture and Subsequent Sufferings of Mrs. Rachel Plummer, 1839, in Parker's Narrative and History of Texas, Louisville: Morning Courier, 1844, pp. 88-118

- Lee, N., Three Years Among the Comanches, in Captured by the Indians, Drimmer, F., editor, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1961, ISBN 0486249018, pp. 277-313

- Babb, T.A., In the Bosom of the Comanches, 1912, Dallas: John F. Worley Printing Co.

- Bell, J.D., A true Story of My Capture by, and Life with the Comanche Indians, in "Every Day Seemed Like a Holiday", The Captivity of Bianca Babb, Gelo, D.J. and Zesch, S., editors, Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 107, No. 1, 2003, pp. 49-67

- Lehmann, H., 1927, 9 Years Among the Indians, 1870-1879, Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, ISBN 0826314171

- Smith, C.L., 1927, The Boy Captives, San Saba: San Saba Printing & Office Supply, ISBN 0-943639-24-7

- Gwynne, S.C., Empire of the Summer Moon, 2010, New York: Scribner, ISBN 9781416591054, p. 112

- Texas Beyond History – The Passing of the Indian Era

- Deloria Jr., Vine J; DeMaille, Raymond J (1999). Documents of American Indian Diplomacy Treaties, Agreements, and Conventions, 1775–1979. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 355, 356, 357, 358. ISBN 978-0-8061-3118-4.

- "THC-Fisher-Miller Land Grant". Texas Historic Markers. Texas Historical Commission. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- "THC-Comanche Treaty". Texas Historical Association. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- Demallie, Raymond J; Deloria, Vine (1999). Documents of American Indian Diplomacy: Treaties, Agreements and Conventions 1775–1979, Vol 1. University of Oklahoma. pp. 1493–1494. ISBN 0-8061-3118-7.

- Germunden, Gerd; Calloway, Colin G; Zantop, Suzanne (2002). Germans and Indians: Fantasies, Encounters, Projections. University of Nebraska Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-8032-6420-5.

- Watson, Larry S (1994). INDIAN TREATIES 1835 to 1902 Vol. XXII – Kiowa, Comanche and Apache. Histree. pp. 15–19.

- Webb, Walter Prescott (1965). The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense. University of Texas Press. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0-292-78110-8.

- Zesch, Scott (2005). The Captured: A True Story of Abduction by Indians on the Texas Frontier. St. Martin's. pp. 239–241. ISBN 978-0-312-31789-8.

- Leahy, Todd; Wilson, Raymond (2009). The A to Z of Native American Movements. Scarecrow Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-8108-6892-2.

- Swan 19

- Daughter Of Dawn, Oklahoma Historical society

- Wallace and Hoebel (1952) p.142

- Wallace and Hoebel (1952) pp.143, 144

- Wallace and Hoebel (1952) p.120

- Wallace and Hoebel (1952) pp.122, 123

- Wallace and Hoebel (1952) p.124

- De Capua, Sarah (2006). The Comanche. Benchmark Books. pp. 22, 23. ISBN 978-0-7614-2249-5.

- Wallace and Hoebel (1952) pp.124, 125

- Wallace and Hoebel (1952) pp.126–132

- Kroeker

- Rollings, Deer (2004) pp 20–24

- "Indian Culture and the Horse" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- Rollings, Deer (2004) pp. 29–30

- Newcomb, Jr., W.W. (2002). The Indians of Texas: from prehistoric to modern times. University of Texas Press. pp. 164. ISBN 978-0-292-78425-3.

- Rollings, Deer (2004) p. 31

- Rollings, Deer (2004) pp. 31, 32

- Rollings, Deer (2004) pp. 32, 33

- Rollings, Deer (2004) p 28

- Rollings, Deer (2004) pp 25, 26

- McLaughlin (1992), 158-81

- McLaughlin (2000), 293–304

- Hämäläinen (2008), p.171

- Holm, Tom (2007). "The Comanche Code Talkers". Code Talkers and Warriors: Native Americans and World War II. Chelsea House Publications. pp. 108–120. ISBN 978-0-7910-9340-5.

- "Comanche Indians Honor D-Day Code-Talkers". D-Day 70th Anniversary. NBC News. June 9, 2014.

Sources

- Kavanagh, Thomas W. (1996). The Comanches: A History 1706–1875. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7792-2.

- Kroeker, Marvin E. (1997). Comanches and Mennonites on the Oklahoma Plains: A.J. and Magdalena Becker and the Post Oak Mission. Fresno, CA: Centers for Mennonite Brethren Studies. ISBN 0-921788-42-8.

- McLaughlin, John E. (1992). "A Counter-Intuitive Solution in Central Numic Phonology". International Journal of American Linguistics. 58 (2): 158–181. doi:10.1086/ijal.58.2.3519754. JSTOR 3519754.

- McLaughlin, John E. (2000). Casad, Gene; Willett, Thomas (eds.). "Language Boundaries and Phonological Borrowing in the Central Numic Languages". Uto-Aztecan: Structural, Temporal, and Geographic Perspectives. Sonora, Mexico: Friends of Uto-Aztecan Universidad de Sonora, División de Humanidades y Bellas Artes, Hermosillo. ISBN 970-689-030-0.

- Meadows, William C (2003). Kiowa, Apache, and Comanche Military Societies: Enduring Veterans, 1800 to the Present. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70518-0.

- Rollings, William H.; Deer, Ada E (2004). The Comanche. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7910-8349-9.

- Swan, Daniel C. (1999). Peyote Religious Art: Symbols of Faith and Belief. Jackson, Mississippi: University of Mississippi Press. ISBN 1-57806-096-6.

- Wallace, Ernest; Hoebel, E. Adamson (1952). The Comanche: Lords of the Southern Plains. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. OCLC 1175397.

- Nye, Wilbur Sturtevant. Carbine and Lance: The Story of Old Fort Sill, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1983

- Leckie, William H.. The Buffalo Soldiers: A Narrative of the Negro Cavalry in the West, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1967

- Fowler, Arlen L.. The Black Infantry in the West, 1869-1891, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1996

Further reading

| Library resources about Comanche |

- Fehrenbach, Theodore Reed (1974). The Comanches: The Destruction of a People. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-394-48856-3. Republished as Fehrenbach, Theodore Reed (2003). The Comanches: The History of a People. New York: Anchor Books. ISBN 1-4000-3049-8.

- Foster, Morris W. (1991). Being Comanche: A Social History of an American Indian Community. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1367-8.

- John, Elizabeth A. H. (1975). Storms Brewed in Other Men's Worlds: The Confrontation of the Indian, Spanish, and French in the Southwest, 1540–1795. College Station: Texas A&M Press. ISBN 0-89096-000-3.

- Kavanagh, Thomas W. (2001). DeMallie, Raymond J. (ed.). "High Plains: Comanche". Handbook of North American Indians. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. 13: 886–906.

- Kavanagh, Thomas W. (2007). "Comanche". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- Kavanagh, Thomas W. (2008). Comanche Ethnography. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2764-4.

- Kenner, Charles (1969). A History of New Mexican-Plains Indian Relations. University of Oklahoma Press. Norman. OCLC 2141.

- Noyes, Stanley (1993). Los Comanches the horse people, 1751–1845. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico. ISBN 0-585-27380-4.

- Spady, James O'Neil (2009). "Reconsidering Empire: Current Interpretations of Native American Agency during Colonization (review)". Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History. 10 (2).

- Thomas, Alfred Barnaby (1940). The Plains Indians and New Mexico, 1751–1778: A collection of documents illustrative of the history of the eastern frontier of New Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. OCLC 3626655.

- Wolff, Gerald W.; Cash, Joseph W. (1976). The Comanche People. Phoenix, Arizona: Indian Tribal Series.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Comanche. |

- Comanche Nation, official website

- The Comanche Language and Cultural Preservation Committee

- Comanche Lodge

- "Comanche". History Channel. Archived from the original on March 8, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2005.

- "Comanche". Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29.

- "Comanche Indians" from the Handbook of Texas Online

- "Photographs of Comanche Indians". Portal to Texas History. Archived from the original on 2007-03-11.

- "The Texas Comanches". Texas Indians.