Brazos River

The Brazos River (/ˈbræzəs/ (![]()

| Brazos River Río de los Brazos de Dios | |

|---|---|

Brazos River downstream of Possum Kingdom Lake, Palo Pinto County, Texas | |

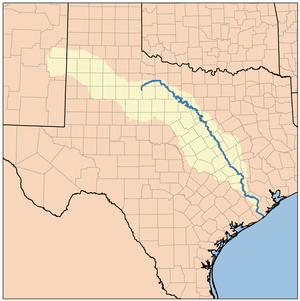

Brazos River watershed | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Llano Estacado |

| Source confluence | Stonewall County, Texas |

| • coordinates | 33°16′07″N 100°0′37″W[1] |

| • elevation | 453 m (1,486 ft) |

| Mouth | Gulf of Mexico |

• location | Brazoria County, Texas |

• coordinates | 28°52′33″N 95°22′42″W[1] |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 1,352 km (840 mi) |

| Basin size | 116,000 km2 (45,000 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Rosharon, TX |

| • average | 237.5 m3/s (8,390 cu ft/s) |

| • minimum | 0.76 m3/s (27 cu ft/s) |

| • maximum | 2,390 m3/s (84,000 cu ft/s) |

The river is closely associated with Texas history, particularly the Austin settlement and Texas Revolution eras. Today major Texas institutions like Baylor University and Texas A&M University are located close to the river, as are parts of metropolitan Houston.

Geography

The Brazos proper begins at the confluence of the Salt Fork and Double Mountain Fork, two tributaries of the Upper Brazos that rise on the high plains of the Llano Estacado, flowing 840 miles (1,350 km) southeast through the center of Texas. Another major tributary of the Upper Brazos is the Clear Fork Brazos River, which passes by Abilene and joins the main river near Graham. Important tributaries of the Lower Brazos include the Paluxy River, the Bosque River, the Little River, Yegua Creek, the Nolan River, the Leon River, the San Gabriel River, the Lampasas River, and the Navasota River.[5]

Initially running east towards Dallas-Fort Worth, the Brazos turns south, passing through Waco and the Baylor University campus, further south to near Calvert, Texas then past Bryan and College Station, then through Richmond, Texas in Fort Bend County, and empties into the Gulf of Mexico in the marshes just south of Freeport.[3]

The main stem of the Brazos is dammed in three places, all north of Waco, forming Possum Kingdom Lake, Lake Granbury, and Lake Whitney. Of these three, Granbury was the last to be completed, in 1969. When its construction was proposed in the mid-1950s, John Graves wrote the book Goodbye to a River. The Whitney Dam, located on the upper Brazos, provides hydroelectric power, flood control, and irrigation to enable efficient cotton growth in the river valley.[4] A small municipal dam (Lake Brazos Dam) is near the downstream city limit of Waco at the end of the Baylor campus; it raises the level of the river through the city to form a town lake. This impoundment of the Brazos through Waco is locally called Lake Brazos. A total of nineteen major reservoirs are located along the Brazos.[6]

North Fork Double Mountain Fork Brazos River at the edge of the Llano Estacado.

North Fork Double Mountain Fork Brazos River at the edge of the Llano Estacado.

Double Mountain Fork Brazos River at the site of former Rath City, Texas.

Double Mountain Fork Brazos River at the site of former Rath City, Texas. The Brazos in north Central Texas.

The Brazos in north Central Texas.- The Brazos in southeast Central Texas west of Bryan, Texas.

History

In 1822, the lower river valley of the Brazos River became one of the major Anglo-American settlement sites in Texas. This was one of the first English-speaking colonies along the Brazos and was founded by Stephen F. Austin at San Felipe de Austin.[4] In 1836, Texas declared independence from Mexico at Washington-on-the-Brazos, a settlement in now Washington County that is known as "the birthplace of Texas".[7] Brazos River was also the scene of a battle between the Texas Navy and Mexican Navy during the Texas Revolution. Texas Navy ship Independence was defeated by one Mexican vessel.

It is unclear when it was first named by European explorers, since it was often confused with the Colorado River not far to the south, but it was certainly seen by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. Later Spanish accounts call it Los Brazos de Dios (the arms of God), for which name there were several different explanations, all involving it being the first water to be found by desperately thirsty parties. In 1842, Indian commissioner of Texas, Ethan Stroud established a trading post on this river.

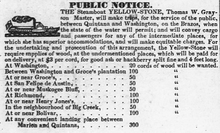

The river was important for navigation before and after the American Civil War, and steam boats sailed as far up the river as Washington-on-the-Brazos.[8] While attempts to improve commercial navigation on the river continued, railroads proved more reliable. The Brazos River also flooded, often seriously, on a regular basis before a piecemeal levee system was replaced, notably in 1913 when a massive flood affected the course of the river. The river is primarily important today as a source of water for power, irrigation, and recreation. The water is administered by the Brazos River Authority.[5]

The 2000 book, Sandbars and Sternwheelers: Steam Navigation on the Brazos by Pamela A. Puryear and Nath Winfield, Jr., with introduction by J. Milton Nance, examines the early vessels that attempted to navigate the Brazos.[9]

On June 2, 2016, the rising of the river required evacuations for portions of Brazoria County.[10]

Brazos watershed

The Brazos River watershed covers a total area of 119,174 square kilometers.[11] Within the watershed lie 42 lakes and rivers which have a combined storage capacity of 2.5 million acre-feet.[12] The Brazos watershed also has an estimated ground water availability of 119,275 acre-feet per year.[13] Approximately 31% of the land use within the watershed is cropland. Approximately 61% is grassland (30%) shrubland (19.8%) and forest (11%) while urban use only makes up 4.6%. The population density within the watershed is 19.5 people per square kilometer.[11]

Water quality concerns

The main water quality issues within the Brazos Watershed are high nutrient loads, high bacterial and salinity levels and low dissolved oxygen. These water quality issues can be attributed to livestock, fertilizer and chemical run off. Sources of run off are croplands, pastures, and industrial sites among others.[14] Fracking is also cause for concern regarding water quality within the Brazos Watershed. The Barnett Shale lies partially within the watershed which is the second largest source of natural gas in the US.[15] Studies have shown that the watershed receiving the most toxic pollution is the lower Brazos river which received 33.4 million pounds of toxic waste in 2012.[16]

Recreation

Canoeing is a very popular recreational activity on the Brazos River with many locations favorable for launching and recovery. The best paddling can be found immediately below Possum Kingdom Lake and Lake Granbury.[17]

Sandbar Camping is also permitted since the entire streambed of the river is considered to be state-owned public property. Fishing, camping, and picnicking are legal here, including on the sandbars.[18] Several scout camps are located along the Brazos River and they support a wide range of water and shoreline activities for scouts, youth groups and family groups.[19]

The Brazos River Authority maintains several public campsites along the river and at the lakes. Hunting and fishing are also permitted at select locations along the river.

Outdoor enthusiasts have the opportunity to view the area's scenery and the wildlife on the river. Fly fishing and river fishing for largemouth bass are common.[20]

Cultural references

- The Lyle Lovett songs "Texas Trilogy: Bosque County Romance" and "Texas River Song" both mention the Brazos.

- The Alan Le May novel The Searchers mentions the Salt Fork of the Brazos River several times as a likely place for the protagonists to find Chief Scar, who is holding the captive child Debbie. In the 1956 film based on the novel, Mose Harper identifies the location of Chief Scar's camp as Seven Fingers, which a group of Texas Rangers identify as Seven Fingers of the Brazos.

- John Graves' travel narrative Goodbye to a River takes place on the Brazos River.

- The Brazos is the setting of the American folk song "Ain't No More Cane".

- “Broke Down on the Brazos” is the first track on Gov’t Mule’s 2009 album By A Thread.

- The Robert Earl Keen song "The Front Porch Song" contains the lyrics "the Brazos still runs muddy like she's run all along".

- The Old Crow Medicine Show song "Take 'em Away" contains the lyrics "Land that I know is where two rivers collide / The Brazos, The Navasota, and the big blue sky".

- The chorus to the Amanda Shires song "Mineral Wells" contains the lyrics "At night I dream I'm in the Brazos River / Pines and cypress of the West Cross Timbers".

- The James Reasoner Civil War Series references the Brazos River many times as it is the goal of one of the main characters to move there after the war is over.

- "Cross the Brazos at Waco" song by Billy Walker.

- The Brazos is mentioned throughout "The Rivers of Texas" performed by Mason Williams

- The Uncle Lucius song "Keep the Wolves Away" mentions the Brazos and Galveston Bay.[21]

See also

|

|

Footnotes

- "Brazos River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- Kammerer, J.C. (1987). "Largest Rivers in the United States". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2006-07-15. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Hendrickson Kenneth E., Jr. (1999-02-15). "Brazos River". The Handbook of Texas Online. The General Libraries at the University of Texas at Austin and the Texas State Historical Association. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved 2006-07-22.

- "Brazos River." Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 11 Aug. 2018. academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/Brazos-River/16291. Accessed 27 Nov. 2018.

- Hendrickson, Jr., Kenneth E. (1981). The Waters of the Brazos: A History of the Brazos River Authority 1929-1979. Waco, TX: The Texian Press.

- "River Basin Map of Texas". Bureau of Economic Geology, University of Texas at Austin. 1996. Archived from the original (JPEG) on 2012-04-10. Retrieved 2006-07-15.

- “Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site.” Texas Parks and Wildlife, 6 Nov. 2018, tpwd.texas.gov/state-parks/washington-on-the-brazos.

- "BRAZOS RIVER". tshaonline.org. 12 June 2010.

- Sandbars and Sternwheelers: Steam Navigation on the Brazos. Texas A&M University Press. 2000. ISBN 1-58544-058-2. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- Foxhall, Emily. "Mandatory evacuations ordered in Brazoria County - Houston Chronicle". Chron.com. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- "USGS EDNA-Derived Watershed Characteristics". edna.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- "River Basins - Brazos River Basin | Texas Water Development Board". www.twdb.texas.gov. Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- "Brazos Valley Groundwater Conservation District". Brazos Valley Groundwater Conservation District. Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- "The Brazos River Authority > About Us > Water Quality > Watershed Protection Plans > Leon River WPP". www.brazos.org. Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- "Texas and fracking - SourceWatch". www.sourcewatch.org. Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- "Southern waters imperiled by toxic pollution". Facing South. 2014-06-23. Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- "Brazos River & Paddling Trails - Parks & Recreation - City of Waco, Texas". Waco-texas.com. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- "The Brazos River Authority > About Us > Education > Water School". Brazos.org. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- "Texas Scout Camps". Maintour.com. 2013-11-26. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- "Home". Brazosriverfishing.com. Retrieved 2016-06-04.

- "Where the muddy Brazos / Spills into the Gulf of Mexico". Genius. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

Further reading

- Archer, Kenna Lang, “A Defiant River, A Technocratic Ideal: Big Dams and Even Bigger Hopes along the Brazos River, 1929–1958,” East Texas Historical Journal, 53 (Fall 2015), 67–87.

- Archer, Kenna Lang. Unruly Waters: A Social and Environmental History of the Brazos River. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2015.

- Hendrickson, Jr., Kenneth E. The Waters of the Brazos: A History of the Brazos River Authority 1929-1979. Waco, TX: The Texian Press, 1981.

- Kimmel, Jim. 2011. Exploring the Brazos River: from beginning to end. Texas A&M Press. College Station, TX.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brazos River. |

External links

- Brazos River from the Handbook of Texas Online

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Brazos River

- Brazos River Authority

- Public domain photos of the Upper Brazos

- Historic photos of Army Corps of Engineers lock and dam projects on the Brazos River, 1910-20s, from the Portal to Texas History

- 1858 map titled Preliminary chart of entrance to Brazos River, Texas from a trigonometrical survey under the direction of A. Bache ; triangulation by J.S. Williams ; topography by J.M. Wampler ; hydrography by the parties under the command of E.J. De Haven & J.K. Duer., hosted by the Portal to Texas History.