Cheyenne language

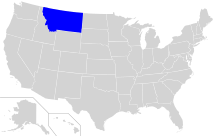

The Cheyenne language (Tsėhésenėstsestȯtse), is the Native American language spoken by the Cheyenne people, predominantly in present-day Montana and Oklahoma, in the United States. It is part of the Algonquian language family. Like all other Algonquian languages, it has complex agglutinative morphology. This language is considered endangered, at different levels, in both states.

| Cheyenne | |

|---|---|

| Tsėhésenėstsestȯtse | |

| Native to | United States |

| Region | Montana and Oklahoma |

| Ethnicity | Cheyenne |

Native speakers | 1,900 (2015 census)[1] |

Algic

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | chy |

| ISO 639-3 | chy |

| Glottolog | chey1247[2] |

| |

Classification

Cheyenne is one of the Algonquian languages, which is a sub-category of the Algic languages. Specifically, it is a Plains Algonquian language. However, Plains Algonquian, which also includes Arapaho and Blackfoot, is an areal rather than genetic subgrouping.

Geographic distribution

Cheyenne is spoken on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana and in Oklahoma. At the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation, where as of March 2013, there were approximately 10,050 enrolled tribal members, of which about 4,939 resided on the reservation; slightly more than a quarter of the population five years or older spoke a language other than English.[3]

Current status

The Cheyenne language is considered "definitely endangered" in Montana and "critically endangered" in Oklahoma by the UNESCO. In Montana the number of speakers are about 1700 according to the UNESCO. In the state of Oklahoma, there are only 400 elderly speakers. There is no current information on any other state in the United States regarding the Cheyenne language.[4]

The 2017 film Hostiles features extensive dialogue in Northern Cheyenne. The film's producers hired experts in the language and culture to ensure authenticity.[5]

Revitalization efforts and education

In 1997, the Cultural Affairs Department of Chief Dull Knife College applied to the Administration for Native Americans for an approximately $50,000 language preservation planning grant. The department wanted to use this money to assess the degree to which Cheyenne was being spoken on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation. Following this, the department wanted to use the compiled data to establish long-term community language goals, and to prepare Chief Dull Knife College to implement a Cheyenne Language Center and curriculum guide.[6] In 2015, the Chief Dull Knife College sponsored the 18th Annual Language Immersion Camp. This event was organized into two weeklong sessions, and its aim was to educate the younger generation on their ancestral language. The first session focused on educating 5-10 year olds, while the second session focused on 11- to 18-year-olds. Certified Cheyenne language instructors taught daily classes. Ultimately, the camp provided approximately ten temporary jobs for fluent speakers on the impoverished reservation. The state of Montana has passed a law that guarantees support for tribal language preservation for Montana tribes.[7] Classes in the Cheyenne language are available at Chief Dull Knife College in Lame Deer, Montana, at Southwestern Oklahoma State University, and at Watonga High School in Watonga, Oklahoma.

Phonology

Vowels

Cheyenne has three basic vowel qualities ([e a o]) that take four tones: high tone as in á [á]); low tone as in a [à]; mid tone as in ā [ā]; and rising tone as in ô [ǒ]. Tones are often not represented in the orthography. Vowels can also be voiceless (e.g. ė [e̥]).[8] The high and low tones are phonemic, while voiceless vowels' occurrence is determined by the phonetic context, making them allophones of the voiced vowels.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mid | e | o | |

| Low | a |

Consonants

The phoneme /h/ is realized as [s] in the environment between /e/ and /t/ (h > s / e _ t). /h/ is realized as [ʃ] between [e] and [k] (h > ʃ / e _ k) i.e. /nahtóna/ nȧhtona - "alien", /nehtóna/ nėstona - "your daughter", /hehke/ heške - "his mother". The digraph "ts" represents assibilated /t/; a phonological rule of Cheyenne is that underlying /t/ becomes affricated before an /e/ (t > ts/_e). Therefore, "ts" is not a separate phoneme, but an allophone of /t/. The sound [x] is not a phoneme, but derives from other phonemes, including /ʃ/ (when /ʃ/ precedes or follows a non-front vowel, /a/ or /o/), and the past tense morpheme /h/ which is pronounced [x] when it precedes a morpheme which starts with /h/.

| Bilabial | Dental | Postalveolar | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | p | t | k | ʔ | |

| Fricative | v | s | ʃ | (x) | h |

| Nasal | m | n |

Orthography

The Cheyenne orthography of 14 letters is neither a pure phonemic system nor a phonetic transcription; it is, in the words of linguist Wayne Leman, a "pronunciation orthography". In other words, it is a practical spelling system designed to facilitate proper pronunciation. Some allophonic variants, such as voiceless vowels, are shown. ⟨e⟩ represents the phoneme symbolized /e/, but is usually pronounced as a phonetic [ɪ] and sometimes varies to [ɛ]. ⟨š⟩ represents /ʃ/.

Feature system for phonemes

The systematic phonemes of Cheyenne are distinguished by seven two-valued features. Scholar Donald G. Frantz defined these features as follows:[9]

- Oral: primary articulation is oral (vs. at the glottis)

- Vocoid (voc): central resonant (oral) continuant

- Syllabic (syl): nuclear to syllable (vs. marginal)

- Closure (clos): stoppage of air flow at point of primary articulation ['non-continuant']

- Nasal (nas): velic is open

- Grave (grv): primary articulation at oral extremity (lips or velum) ['non-coronal' for consonants, 'back' for vowels]

- Diffuse (dif): primary articulation is relatively front ['anterior']

| ʔ | h | a | o | e | m | n | p | k | t | b | s | š | x | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| oral | − | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) | + | + | + | (+) | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| voc | (−) | + | (+) | (+) | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | − | − | − | − |

| syl | (−) | − | + | + | + | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| clos | (+) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | (+) | (+) | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| nas | 0 | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) | + | + | − | (−) | − | (−) | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| grv | 0 | − | + | (−) | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | |

| dif | 0 | − | − | + | + | (+) | + | − | (+) | + | + | − | − |

0 indicates the value is indeterminable/irrelevant. A blank indicates the value is specifiable, but context is required (even though any value could be inserted because the post-cyclical rules would change the value to the correct one). Parentheses enclose values that are redundant according to the phonological rules; these values simply represent the results of these rules.[9]

Voicing

Cheyenne has 14 orthographic letters representing 13 phonemes. [x] is written as x orthographically but is not a phoneme. This count excludes the results of allophonic devoicing, which are spelled with a dot overtop vowels. Devoicing naturally occurs in the last vowel of a word or phrase. It can also occur in vowels at the penultimate and prepenultimate positions within a word. Non-high [a] and [o] is also usually devoiced preceding h plus a stop. Phonemic /h/ is absorbed by a preceding voiceless vowel. Examples are given below.

Penultimate devoicing

- /hohkoʃ/ hohkȯxe 'ax';

- /tétahpetáht/ tsétȧhpétȧhtse 'the one who is big';

- /mótehk/ motšėške 'knife'

Devoicing occurs when certain vowels directly precede the consonants [t], [s], [ʃ], [k], or [x] that are followed by an [e]. This rule is linked to the rule of e-epenthesis, which simply states that [e] appears in the environment of a consonant and a word boundary.[10]

Prepenultimate devoicing

- /tahpeno/ tȧhpeno 'flute';

- /kosáné/ kȯsâne 'sheep (pl.)';

- /mahnohtehtovot/ mȧhnȯhtsėstovȯtse 'if you ask him'

A vowel that does not have a high pitch is devoiced if it is followed by a voiceless fricative and not preceded by [h].[10]

Special [a] and [o] devoicing

- /émóheeohtéo/ émôheeȯhtseo'o 'they are gathering';

- /náohkeho'sóe/ náȯhkėho'soo'e 'I regularly dance';

- /nápóahtenáhnó/ nápôȧhtsenáhno 'I punched him in the mouth'

Non-high [a] and [o] become at least partially devoiced when they are preceded by a voiced vowel and followed by an [h], a consonant and two or more syllables.[11]

Consonant devoicing

émane [ímaṅi] 'He is drinking.'

When preceding a voiceless segment, a consonant is devoiced.[11]

h-absorption

- -pėhévoestomo'he 'kind' + -htse 'imperative suffix' > -pėhévoestomo'ėstse

- tsé- 'conjunct prefix' + -éna'he 'old' + -tse '3rd pers. Suffix' > tsééna'ėstse 'the one who is old'

- né + 'you' + -one'xȧho'he 'burn' + tse 'suffix for some 'you-me' transitive animate forms' > néone'xȧho'ėstse ' you burn me'

The [h] is absorbed when preceded or followed by voiceless vowels.[12]

Pitch and tone

There are several rules that govern pitch use in Cheyenne. Pitch can be ˊ = high, unmarked = low, ˉ = mid, and ˆ = raised high. According to linguist Wayne Leman, some research shows that Cheyenne may have a stress system independent from that of pitch. If this is the case, the stress system's role is very minor in Cheyenne prosody. It would have no grammatical or lexical function, unlike pitch.[13]

High-raising

A high pitch becomes a raised high when it is not followed by another high vowel and precedes an underlying word-final high.[14]

- /ʃéʔʃé/ šê'še 'duck';

- /sémón/ sêmo 'boat'

Low-to-high raising

A low vowel is raised to the high position when it precedes a high and is followed by a word final high.[14]

- /méʃené/ méšéne 'ticks';

- /návóomó/ návóómo 'I see him';

- /póesón/ póéso 'cat'

Low-to-mid raising

A low vowel becomes a mid when it is followed by a word-final high but not directly preceded by a high vowel.[14]

- /kosán/ kōsa 'sheep (sg.)';

- /heʔé/ hē'e 'woman';

- /éhomosé/ éhomōse 'he is cooking'

High pushover

A high vowel becomes low if it comes before a high and followed by a phonetic low.[14]

- /néháóénáma/ néhâoenama 'we (incl) prayed';

- /néméhótóne/ némêhotone 'we (incl) love him';

- /náméhósanémé/ námêhosanême 'we (excl) love'

Word-medial high raising

According to Leman, "some verbal prefixes and preverbs go through the process of Word-Medial High-Raising. A high is raised if it follows a high (which is not a trigger for the High Push-Over rule) and precedes a phonetic low. One or more voiceless syllables may come between the two highs. (A devoiced vowel in this process must be underlyingly low, not an underlyingly high vowel which has been devoiced by the High-Pitch Devoicing rule.)"[15]

- /émésehe/ émêsehe 'he is eating';

- /téhnémenétó/ tséhnêmenéto 'when I sang';

- /násáamétohénoto/ násâamétȯhênoto 'I didn't give him to him'

Tone

Syllables with high pitch (tone) are relatively high pitched and are marked by an acute accent, á, é, and ó. The following pairs of phrases demonstrate pitch contrasts in the Cheyenne language:

- maxháeanáto (if I am hungry)

- maxháeanato (if you are hungry)

- hótame (dog)

- hotāme (dogs)

As noted by Donald G. Frantz, phonological rules dictate some pitch patterns, as indicated by the frequent shift of accent when suffixes are added (e.g. compare matšėškōme "raccoon" and mátšėškomeo'o "raccoons"). In order for the rules to work, certain vowels are assigned inherent accent. For example, the word for "badger" has a permanent accent position: ma'háhko'e (sg.), ma'háhko'eo'o (pl.)[16]

Nonnasal reflexes of Proto-Algonquian *k

The research of linguist Paul Proulx provides an explanation for how these reflexes develop in Cheyenne: "First, *n and *h drop and all other consonants give glottal catch before *k. *k then drops except in element-final position. Next, there is an increment before any remaining *k not preceded by a glottal catch: a secondary h (replaced by š after e) ) in words originating in the Cheyenne Proper dialect, and a vowel in those originating in the Sutaio (So'taa'e) dialect. In the latter dialect the *k gives glottal catch in a word-final syllable (after the loss of some final syllables) and drops elsewhere, leaving the vowel increment. Sutaio 'k clusters are all reduced to glottal catch."[17]

Grammar

Cheyenne is a morphologically polysynthetic language with a sophisticated, agglutinating verb system contrasting a relatively simple noun structure.[18] Many Cheyenne verbs can stand alone in sentences, and can be translated by complete English sentences. Aside from its verb structure, Cheyenne has several grammatical features that are typical of Algonquian languages, including an animate/inanimate noun classification paradigm, an obviative third person and distinction of clusivity in the first person plural pronoun.[19]

Order and mode

Like all Algonquian languages, Cheyenne shows a highly developed modal paradigm.[20] Algonquianists traditionally describe the inflections of verbs in these languages as being divided into three "orders," with each order further subdivided into a series of "modes," each of which communicates some aspect of modality.[20][21][22] The charts below provide examples of verb forms of every order in each mode, after Leman (2011)[23] and Mithun (1999).[20]

Independent order

This order governs both declarative and interrogative statements. The modes of this order are generally subdivided along lines of evidentiality.[22]

| Mode | Example | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Indicative | épėhêvahe | "he is good" |

| Interrogative | épėhêvȧhehe | "is he good?" |

| Inferential | mópėhêvȧhehêhe | "he must be good" |

| Attributive | épėhêvahesėstse | "he is said to be good" |

| Mediate | éhpehêvahêhoo'o | "long ago he was good" |

Conjunct order

This order governs a variety of dependent clause types.[22] Leman (2011) characterizes this order of verbs as requiring other verbal elements in order to establish complete meaning.[24] Verbs in the conjunct order are marked with a mode-specific prefix and a suffix marking person, number and animacy.[25]

| Mode | Example | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Indicative | tséhpėhêvaese | "when he was good" |

| Subjunctive | mȧhpėhévaestse | "when he is good" (unrealized) |

| Iterative | ho'pėhévȧhesėstse | "whenever he is good" |

| Subjunctive Iterative | ohpėhévȧhesėstse | "when he is generally good" |

| Participle | tséhpėhêvaestse | "the one who is good" |

| Interrogative | éópėhêvaestse | "whether he is good" |

| Obligative | ahpėhêvȧhesėstse | "he ought to be good" |

| Optative | momóxepėhévaestse | "I wish he would be good" |

| Negative inferential | móho'nópėhévaestse | "he must not be good" |

Imperative order

The third order governs commands. Cheyenne, in common with several other North American languages,[20] distinguishes two types of imperative mood, one indicating immediate action, and the other indicating delayed action.[26][27]

| Mode | Example | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate | méseestse | "eat!" |

| Delayed | méseheo'o | "eat later!" |

| Hortative | mésėheha | "let him eat!" |

Verb morphology

The Cheyenne verb system is very complex and verb constructions are central to the morphosyntax of the language,[28][29] to the point that even adjectives[30] and even some nouns[31] are largely substantive in nature. Verbs change according to a number of factors, such as modality, person and transitivity, as well as the animacy of the referent, each of these categories being indicated by the addition of an affix to the basic verb stem.[32] There are also several instrumental, locative and adverbial affixes that add further information to the larger verb construction. This can result in very long, complex verbs that are able to stand alone as entire sentences in their own right. All Cheyenne verbs have a rigid templatic structure.[25] The affixes are placed according to the following paradigm:

Pronominal affixes

Cheyenne represents the participants of an expression not as separate pronoun words but as affixes on the verb. There are three basic pronominal prefixes in Cheyenne:[33]

- ná- first person

- né- second person

- é- third person

These three basic prefixes can be combined with various suffixes to express all of Cheyenne's pronominal distinctions. For example, the prefix ná- can be combined on a verb with the suffix -me to express the first person plural exclusive.

Tense

Tense in Cheyenne is expressed by the addition of a specific tense morpheme between the pronominal prefix and the verb stem. Verbs do not always contain tense information, and an unmarked present tense verb can be used to express both past and "recent" present tense in conversation. Thus, návóómo could mean both "I see him" and "I saw him"[34] depending on the context.

Far past tense is expressed by the morpheme /-h-/, which changes to /-x-/, /-s-/, /-š-/ or /-'-/ before the -h, -t, -k and a vowel, respectively. Thus:

- návóómo I see him

- náhvóómo I saw him

Similarly, the future tense is expressed by the morpheme /-hte/, which changes to -htse after the ná- pronominal, -stse after ne- and -tse in the third-person, with the third-person prefix dropped altogether.[34]

Directional affixes

These prefixes address whether the action of the verb is moving "toward" or "away from" some entity, usually the speaker.[35]

- -nėh- toward

- -nex- toward (before -h)

- -ne'- toward (before a vowel)

- -nes- toward (before -t)

- -ta- away from

Preverbs

Following Algonquianist terminology, Leman (2011) describes "preverbs", morphemes which add adjectival or adverbial information to the verb stem. Multiple preverbs can be combined within one verb complex. The following list represents only a small sample.[36]

- -emóose- secretly

- -nésta- previously

- -sé'hove- suddenly

- -áhane- extremely

- -táve- slightly

- -ohke- regularly

- -pȧháve- good, well

- -ma'xe- much, a lot

- -hé- for the purpose of

- -ha'ke- slowly, softly

- -hoove- mistakenly

Medial affixes

This large group of suffixes provide information about something associated with the root, usually communicating that the action is done with or to a body part.[35] Thus: énėše'xahtse (he-wash-mouth) = "he gargled."[37] Following is a sample of medial suffixes:[38]

- -ahtse mouth

- -éné face

- -na'evá arm

- -vétová body

- -he'oná hand

- -hahtá foot

Medial suffixes can also be used with nouns to create compound words or to coin entirely new words from existing morphemes, as in:

ka'énė-hôtame [short-face-dog] = bulldog[37]

Final affixes

Cheyenne verbs take different object agreement endings depending upon the animacy of the subject and the transitivity of the verb itself. Intransitive verbs take endings depending upon the animacy of their subject, whereas transitive verbs take endings that depend upon the animacy of their object. All verbs can therefore be broadly categorized into one of four classes: Animate Intransitive (AI), Inanimate Instransitive (II), Transitive Animate (TA) and Transitive Inanimate (TI).[39] Following are the most common object agreement markers for each verb class.[35]

- -e Animate Intransitive (AI)

- -ó Inanimate Intransitive (II)

- -o Transitive Animate (TA)

- -á/-é Transitive Inanimate (TI)

Negation

Verbs are negated by the addition of the infix -sâa- immediately after the pronominal affix. This morpheme changes to sáa- in the absence of a pronominal affix, as occurs in the imperative and in some future tense constructions.[40]

Nouns

Nouns are classified according to animacy.[41] They change according to grammatical number (singular and plural) but are not distinguished according to gender[42] or definiteness.[43]

Obviation

When two third persons are referred to by the same verb, the object of the sentence becomes obviated, what Algonquianists refer to as a "fourth person."[44] It is essentially an "out of focus" third person.[45] As with possessive obviation above, the presence of a fourth person triggers morphological changes in both the verb and noun. If the obviated entity is an animate noun, it will be marked with an obviative suffix, typically -o or -óho. For example:

- návóómo hetane "I saw a man"

- he'e évôomóho hetanóho "The woman saw a man"

Verbs register the presence of obviated participants whether or not they are present as nouns. These forms could be likened to a kind of passive voice, although Esteban (2012) argues that since Cheyenne is a "reference-dominated language where case marking and word order are governed by the necessity to code pragmatic roles," a passive-like construction is assumed.[46] This phenomenon is an example of typical Algonquian "person hierarchy," in which animacy and first personhood take precedence over other forms.[32]

Number

Both animate and inanimate nouns are pluralized by the addition of suffixes.[47][48] These suffixes are irregular and can change slightly according to a complex system of phonological rules.[49]

- -(h)o, -(n)é Inanimate plural

- -(n)ȯtse Animate plural

Possession

Possession is denoted by a special set of pronominal suffixes. Following is a list of the most common possession prefixes, although rarely some words take different prefixes.[45][50]

- na- first person

- ne- second person

- he- third person

Generally, possessive prefixes take a low pitch on the following vowel.[33]

When a third person animate noun is possessed by another third person, the noun becomes obviated and takes a different form. Much of the time, this obviated form is identical to the noun's regular plural form,[45] with only a few exceptions.[51] This introduces ambiguity in that it is not always possible to tell whether an obviated noun is singular or plural.[45]

Historical development

Like all the Algonquian languages, Cheyenne developed from a reconstructed ancestor referred to as Proto-Algonquian (often abbreviated "PA"). The sound changes on the road from PA to modern Cheyenne are complex, as exhibited by the development of the PA word *erenyiwa "man" into Cheyenne hetane:

- First, the PA suffix -wa drops (*erenyi)

- The geminate vowel sequence -yi- simplifies to /i/ (semivowels were phonemically vowels in PA; when PA */i/ or */o/ appeared before another vowel, it became non-syllabic) (*ereni)

- PA */r/ changes to /t/ (*eteni)

- /h/ is added before word-initial vowels (*heteni)

- Due to a vowel chain-shift, the vowels in the word wind up as /e/, /a/ and /e/ (PA */e/ sometimes corresponds to Cheyenne /e/ and sometimes to Cheyenne /a/; PA */i/ almost always corresponds to Cheyenne /e/, however) (hetane).

PA *θk has the Sutaio reflex ' in e-nete'e "she tells lies", but the Cheyenne-Proper reflex 'k in hetone'ke "tree-bark". According to linguist Paul Proulx, this gave off the appearance that "speakers of both Cheyenne dialects—perhaps mixed bands—were involved in the Arapaho contact that led to this unusual reflex of PA *k.".[17]

Lexicon

Some Cheyenne words (with the Proto-Algonquian reconstructions where known):

Translations

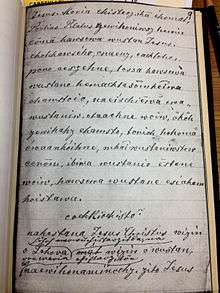

Early work was done on the Cheyenne language by Rodolphe Charles Petter, a Mennonite missionary based in Lame Deer, Montana, from 1916.[52] Petter published a mammoth dictionary of Cheyenne in 1915.[53]

Notes

- Cheyenne at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Cheyenne". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- "Northern Cheyenne Tribe website". Archived from the original on 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2020-07-19.

- "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger". Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- Schilling, Vincent (January 8, 2018). "'Hostiles' Movie Starring Wes Studi, Christian Bale Will Screen in DC: National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), applauds Hostiles for 'authentic representation of Native peoples' and accurate speaking of Native languages". Indian Country Today. Archived from the original on January 22, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- Littlebear, Richard (2003). "Chief Dull Knife Community is Strengthening the Northern Cheyenne Language and Culture" (PDF). Arizona State University.

- Caufield, Clara (2015). "Keeping the Cheyenne language alive". 29 (8): 19. ISSN 1548-4939. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Linguist Wayne Leman included one more variant in his International Journal of American Linguistics (1981) article on Cheyenne pitch rules, a lowered-high pitch (e.g. à), but has since recognized that this posited pitch is the same as a low tone.

- Frantz, Donald G. (1972-01-01). "Cheyenne Distinctive Features and Phonological Rules". International Journal of American Linguistics. 38 (1): 6–13. doi:10.1086/465178. JSTOR 1264497.

- Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 215

- Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 218

- Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 217

- Leman, Wayne (1981-01-01). "Cheyenne Pitch Rules". International Journal of American Linguistics. 47 (4): 283–309. doi:10.1086/465700. JSTOR 1265058.

- Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 219

- Leman, 1979, Cheyenne Grammar Notes p. 220

- Frantz, Donald G. (1972-01-01). "The Origin of Cheyenne Pitch Accent". International Journal of American Linguistics. 38 (4): 223–225. doi:10.1086/465218. JSTOR 1264297.

- Proulx, Paul (1982-01-01). "Proto-Algonquian *k in Cheyenne". International Journal of American Linguistics. 48 (4): 467–471. doi:10.1086/465756. JSTOR 1264849.

- Mithun 1999, p.338.

- Mithun 1999, p.338-40.

- Mithun 1999, p.172.

- Leman 2011, p.24.

- Murray 2016, p.243.

- Leman 2011, p.24-42.

- Leman 2011, p.19.

- Murray 2016, p.244.

- Leman 2011, p.18.

- Murray 2016, p.242.

- Leman 2011, p.17.

- Petter 1905, p.451.

- Petter 1905, p.457.

- Petter 1915, p.iv.

- Leman 2011, p.22.

- Leman 2011, p.20.

- Leman 2011, p.191.

- Leman 2011, p.23.

- Leman 2011, p.181.

- Leman 2011, p.165.

- Leman 2011, p.163.

- Leman 2011, p.17-18.

- Leman 2011, p.25

- Leman 2011, p.5.

- Petter 1905, p.456.

- Petter 1905, p.459.

- Leman 2011, p.21.

- Leman 2011, p.11.

- Esteban 2012, p.93.

- Leman 2011, p.8.

- Petter 1905, p.454.

- Leman 2011, p.214.

- Petter 1905, p.455.

- Leman 2011, p.171.

- "Petter, Rodolphe Charles (1865-1947)" Archived June 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, accessed September 20, 2009

- "Petter, 1915, English-Cheyenne Dictionary.

References

- Esteban, Avelino Corral. "Does There Exist Passive Voice in Lakhota and Cheyenne?" Revista de Lingüística y Lenguas Aplicadas vol.7 (2012): 93.

- Fisher Louise, Leroy Pine Sr., Marie Sanchez, and Wayne Leman, 2004. Cheyenne Dictionary. Lame Deer, Montana: Chief Dull Knife College.

- Mithun, Marianne. "The Languages of Native North America." Cambridge University Press, 1999

- Murray, Sarah E. "Two Imperatives in Cheyenne: Some Preliminary Distinctions." In Monica Macaulay, et al. Papers of the Forty-Fourth Algonquian Conference. State University of New York Press. pp. 242–56.

- Petter, Rodolphe. "English-Cheyenne Dictionary." Kettle Falls, WA: Rodolphe Petter, 1915

- Petter, Rodolphe. "Sketch of the Cheyenne Grammar." Lancaster, PA: American Anthropological Association, 1905

- Leman, Wayne. "A Reference Grammar of the Cheyenne Language." Lulu Press, 2011

External links

| Cheyenne edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Cheyenne online dictionary, maintained at Chief Dull Knife College

- Modern Southern Cheyenne alphabet and pronunciation key

- FREELANG Cheyenne-English and English-Cheyenne online dictionary

- Cheyenne language flashcards at Quizlet, based on Risingsun, Ted; Leman, Wayne (1999). Let's Talk Cheyenne (2 Audio CDs with Booklet). ISBN 9781579700928.

- Cheyenne Language Website

- Native Languages of the Americas: Cheyenne

- Portions of the Anglican/Episcopal Prayer Book Cheyenne

- Martin Luther's Small Catechism in Cheyenne

- Lomax Collection Recording of Cheyenne (1956), Conversation

- OLAC resources in and about the Cheyenne language