Yajnavalkya

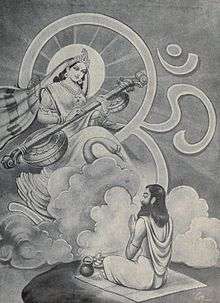

Yajnavalkya or Yagyavlkya (Sanskrit: याज्ञवल्क्य, Yājñavalkya) was a Hindu Vedic sage.[1] He is mentioned in the Upanishads,[2] and likely lived in the Videha region of ancient India, approximately between the 8th century BCE,[3][4] and the 7th century BCE.[5] Yajnavalkya is considered one of the earliest philosophers in recorded history.[3] Yajnavalkya proposes and debates metaphysical questions about the nature of existence, consciousness and impermanence, and expounds the epistemic doctrine of neti neti ("not this, not this") to discover the universal Self and Ātman.[6] His ideas for renunciation of worldly attachments have been important to Hindu sannyasa traditions.[7]

Yajnavalkya | |

|---|---|

| Personal | |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Spouse | Maitreyi, Katyayani |

| Philosophy | Advaita |

| Honors | Rishi |

Yajnavalkya is credited for coining the Advaita (non-dualism, monism), another important tradition within Hinduism.[8] Texts attributed to him, include the Yajnavalkya Smriti, Yoga Yajnavalkya and some texts of the Vedanta school.[9][10] He is also mentioned in various Brahmanas and Aranyakas.[9]

He welcomed participation of women in Vedic studies, and Hindu texts contain his dialogues with two women philosophers, Gargi Vachaknavi and Maitreyi.[11]

History

Yanjavalkya is estimated to have lived in around the 8th century BCE,[12] or 7th century BCE.[5]

In the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, a set of dialogues suggest Yajnavalkya has two wives, one Maitreyi who challenges Yajnavalkya with philosophical questions like a scholarly wife; the other Katyayani who is silent but mentioned as a housewife.[13] While Yajnavalkya and Katyayani lived in contented domesticity, Maitreyi studied metaphysics and engaged in theological dialogues with her husband in addition to "making self-inquiries of introspection".[13][14] In contrast to the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, the epic Mahabharata states Maitreyi is a young beauty who is an Advaita scholar but never marries.[15]

His name Yajnavalkya is derived from yajna which connotes ritual. However, states Frits Staal, Yajnavalkya was "a thinker, not a ritualist".[1]

Texts

Yajnavalkya is associated with several other major ancient texts in Sanskrit, namely the Shukla Yajurveda, the Shatapatha Brahmana, the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, the Dharmasastra named Yājñavalkya Smṛti, Vriddha Yajnavalkya, and Brihad Yajnavalkya.[9] He is also mentioned in the Mahabharata and the Puranas,[16][17] as well as in ancient Jainism texts such as the Isibhasiyaim.[18]

Another important and influential Yoga text in Hinduism is named after him, namely Yoga Yajnavalkya, but its author is unclear. The actual author of Yoga Yajnavalkya text was probably someone who lived many centuries after the Vedic sage Yajnavalkya, and is unknowIng Yajnavalkya was father, Vajasaneya was his biological son, who wrote or explained Yoga Yajnavalkya in writings to his descendants! [19] Ian Whicher, a professor of Religion at the University of Manitoba, states that the author of Yoga Yajnavalkya may be an ancient Yajnavalkya, but this Yajnavalkya is not to be confused with the Vedic-era Yajnavalkya "who is revered in Hinduism for Brihadaranyaka Upanishad".[20]

According to Vishwanath Narayan Mandlik, these references to Yajnavalkya in other texts, in addition to the eponymous Yoga Yajnavalkya, may be to different sages with the same name.[17]

Ideas

On karma and rebirth

One of the early expositions of karma and rebirth theories appear in the discussions of Yajnavalkya.[21]

Now as a man is like this or like that,

according as he acts and according as he behaves, so will he be;

a man of good acts will become good, a man of bad acts, bad;

he becomes pure by pure deeds, bad by bad deeds;

And here they say that a person consists of desires,

and as is his desire, so is his will;

and as is his will, so is his deed;

and whatever deed he does, that he will reap.

Max Muller and Paul Deussen, in their respective translations, describe the Upanishad's view of "Soul, Self" and "free, liberated state of existence" as, "[Self] is imperishable, for he cannot perish; he is unattached, for he does not attach himself; unfettered, he does not suffer, he does not fail. He is beyond good and evil, and neither what he has done, nor what he has omitted to do, affects him. (...) He therefore who knows it [reached self-realization], becomes quiet, subdued, satisfied, patient, and collected. He sees self in Self, sees all as Self. Evil does not overcome him, he overcomes all evil. Evil does not burn him, he burns all evil. Free from evil, free from spots, free from doubt, he became Atman-Brâhmana; this is the Brahma-world, O King, thus spoke Yajnavalkya."[23][24]

On spiritual liberation

The section 4.3 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad is attributed to Yajnavalkya, and it discusses the premises of moksha (liberation, freedom), and provides some of its most studied hymns. Paul Deussen calls it, "unique in its richness and warmth of presentation", with profoundness that retains its full worth in modern times.[25]

On love and soul

The Maitreyi-Yajnavalkya dialogue of Brihadaranyaka Upanishad states that love is driven by a person's soul, and it discusses the nature of Atman and Brahman and their unity, the core of Advaita philosophy.[26][27] The Maitreyi-Yajnavalkya dialogue has survived in two manuscript recensions from the Madhyamdina and Kanva Vedic schools; although they have significant literary differences, they share the same philosophical theme.[28]

This dialogue appears in several Hindu texts; the earliest is in chapter 2.4 – and modified in chapter 4.5 – of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, one of the principal and oldest Upanishads.[29][30] Adi Shankara, a scholar of the influential Advaita Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy, wrote in his Brihadaranyakopanishad bhashya that the purpose of the Maitreyi-Yajnavalkya dialogue in chapter 2.4 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad is to highlight the importance of the knowledge of Atman and Brahman, and to understand their oneness.[31][32] According to Shankara, the dialogue suggests renunciation is prescribed in the Sruti (vedic texts of Hinduism), as a means to knowledge of the Brahman and Atman.[33] He adds, that the pursuit of self-knowledge is considered important in the Sruti because the Maitreyi dialogue is repeated in chapter 4.5 as a "logical finale" to the discussion of Brahman in the Upanishad.[34]

Concluding his dialogue on the "inner self", or soul, Yajnavalkaya tells Maitreyi:[29]

One should indeed see, hear, understand and meditate over the Self, O Maitreyi;

indeed, he who has seen, heard, reflected and understood the Self – by him alone the whole world comes to be known.— Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 2.4.5b[35]

After Yajnavalkya leaves and becomes a sannyasi, Maitreyi becomes a sannyasini – she too wanders and leads a renunciate's life.[36]

See also

References

- Frits Staal (2008). Discovering the Vedas: Origins, Mantras, Rituals, Insights. Penguin Books. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-14-309986-4., Quote: "Yajnavalkya, a Vedic sage, taught..."

- Patrick Olivelle (1998). Upaniṣads. Oxford University Press. pp. 3, 52–71. ISBN 978-0-19-283576-5.

- Ben-Ami Scharfstein (1998), A comparative history of world philosophy: from the Upanishads to Kant, Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 9-11

- H. C. Raychaudhuri (1972), Political History of Ancient India, Calcutta: University of Calcutta, pp. 8-10, 21–25

- Patrick Olivelle (1998). Upaniṣads. Oxford University Press. p. xxxvi with footnote 20. ISBN 978-0-19-283576-5.

- Jonardon Ganeri (2007). The Concealed Art of the Soul: Theories of Self and Practices of Truth in Indian Ethics and Epistemology. Oxford University Press. pp. 27–28, 33–35. ISBN 978-0-19-920241-6.

- Patrick Olivelle (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads: Hindu Scriptures on Asceticism and Renunciation. Oxford University Press. pp. 92, 140–146. ISBN 978-0-19-536137-7.

- Frits Staal (2008). Discovering the Vedas: Origins, Mantras, Rituals, Insights. Penguin Books. pp. 365 note 159. ISBN 978-0-14-309986-4.

- I Fisher (1984), Yajnavalkya in the Sruti traditions of the Veda, Acta Orientalia, Volume 45, pages 55–87

- Patrick Olivelle (1993). The Asrama System: The History and Hermeneutics of a Religious Institution. Oxford University Press. pp. 92 with footnote 63, 144, 163. ISBN 978-0-19-534478-3.

- Patrick Olivelle (1998). Upaniṣads. Oxford University Press. pp. xxxvi–xxxix. ISBN 978-0-19-283576-5.

- Ben-Ami Scharfstein (1998). A Comparative History of World Philosophy: From the Upanishads to Kant. State University of New York Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-7914-3683-7.

- Pechilis 2004, pp. 11–15.

- John Muir, Metrical Translations from Sanskrit Writers, p. 251, at Google Books, page 246–251

- John Muir, Metrical Translations from Sanskrit Writers, p. 251, at Google Books, page 251–253

- White 2014, pp. xiii, xvi.

- Vishwanath Narayan Mandlik, The Vyavahára Mayúkha, in Original, with an English Translation at Google Books, pages lvi, xlviii–lix

- Hajime Nakamura (1968), Yajnavalkya and other Upanishadic thinkers in a Jain tradition, The Adyar Library Bulletin, Volume 31–32, pages 214–228

- Larson & Bhattacharya 2008, pp. 476–477.

- Ian Whicher (1999), The Integrity of the Yoga Darsana: A Reconsideration of Classical Yoga, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791438152, pages 27, 315–316 with notes

- Hock, Hans Henrich (2002). "The Yajnavalkya Cycle in the Brhad Aranyaka Upanisad". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 122 (2): 278–286. doi:10.2307/3087621.

- Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 4.4.5-6 Berkley Center for Religion Peace & World Affairs, Georgetown University (2012)

- Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 475-507

- Max Muller, Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 4.3-4, Oxford University Press, pages 161-181 with footnotes

- Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 482

- Hino 1991, pp. 94–95.

- Brereton 2006, pp. 323–345.

- Brereton 2006, pp. 323–45.

- Marvelly 2011, p. 43.

- Hume 1967, pp. 98–102, 146–48.

- Hino 1991, pp. 5–6, 94.

- Paul Deussen (2015). The System of the Vedanta: According to Badarayana's Brahma-Sutras and Shankara's Commentary thereon. KB Classics Reprint. pp. 173–174. ISBN 978-1-5191-1778-6.

- Hino 1991, pp. 54–59, 94–95, 145–149.

- Hino 1991, p. 5.

- Deussen 2010, p. 435.

- "Yajnavalkya's Marriages and His Later Life". Shukla Yajurveda. Shuklayajurveda Organization. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

Bibliography

- Brereton, Joel P. (2006). "The Composition of the Maitreyī Dialogue in the Brhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 126 (3). JSTOR 20064512.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Deussen, Paul (2010). Sixty Upanishads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1468-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hino, Shoun (1991). Suresvara's Vartika On Yajnavalkya'S-Maitreyi Dialogue (2nd ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0729-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hume, Robert (1967). Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. (Translator), Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Larson, Gerald James; Bhattacharya, Ram Shankar (2008). The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies: Yoga: India's philosophy of meditation. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-3349-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marvelly, Paula (2011). Women of Wisdom. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78028-367-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mohan, A. G., translator (2013). Yoga Yajnavalkya (2nd ed.). Svastha Yoga. ISBN 978-9810716486.

- Pechilis, Karen (2004). The Graceful Guru: Hindu Female Gurus in India and the United States. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514537-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, David Gordon (2014). The "Yoga Sutra of Patanjali": A Biography. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691143774.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Joseph, George G. (2000). The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics, 2nd edition. Penguin Books, London. ISBN 0-691-00659-8.

- Kak, Subhash C. (2000). 'Birth and Early Development of Indian Astronomy'. In Selin, Helaine (2000). Astronomy Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Astronomy (303-340). Boston: Kluwer. ISBN 0-7923-6363-9.

- Teresi, Dick (2002). Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science - from the Babylonians to the Maya. Simon & Schuster, New York. ISBN 0-684-83718-8.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Yajnavalkya |

- Works by Yajnavalkya at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Yajnavalkya at Internet Archive

- Sukla Yajur Veda from http://www.shuklayajurveda.org

- Yogeeswara Yagnavalkya