Workers' self-management

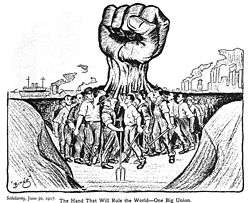

Workers' self-management, also referred to as labor management and organizational self-management, is a form of organizational management based on self-directed work processes on the part of an organization's workforce. Self-management is a defining characteristic of socialism, with proposals for self-management having appeared many times throughout the history of the socialist movement, advocated variously by democratic, libertarian and market socialists as well as anarchists and communists.[1]

There are many variations of self-management. In some variants, all the worker-members manage the enterprise directly through assemblies while in other forms workers exercise management functions indirectly through the election of specialist managers. Self-management may include worker supervision and oversight of an organization by elected bodies, the election of specialized managers, or self-directed management without any specialized managers as such.[2] The goals of self-management are to improve performance by granting workers greater autonomy in their day-to-day operations, boosting morale, reducing alienation and eliminating exploitation when paired with employee ownership.[3]

An enterprise that is self-managed is referred to as a labour-managed firm. Self-management refers to control rights within a productive organization, being distinct from the questions of ownership and what economic system the organization operates under.[4] Self-management of an organization may coincide with employee ownership of that organization, but self-management can also exist in the context of organizations under public ownership and to a limited extent within private companies in the form of co-determination and worker representation on the board of directors.

Economic theory

| This is part of a series on |

| Syndicalism |

|---|

|

|

Variants

|

|

Economics |

|

|

An economic system consisting of self-managed enterprises is sometimes referred to as a participatory economy, self-managed economy, or cooperative economy. This economic model is a major version of market socialism and decentralized planned economy, stemming from the notion that people should be able to participate in making the decisions that affect their well-being. The major proponents of self-managed market socialism in the 20th century include the economists Benjamin Ward, Jaroslav Vanek and Branko Horvat.[5] The Ward–Vanek model of self-management involves the diffusion of entrepreneurial roles amongst all the partners of the enterprise.

Branko Horvat notes that participation is not simply more desirable, but also more economically viable than traditional hierarchical and authoritarian management as demonstrated by econometric measurements which indicate an increase in efficiency with greater participation in decision-making. According to Horvat, these developments are moving the world toward a self-governing socialistic mode of organization.[6]

In the economic theory of self-management, workers are no longer employees but partners in the administration of their enterprise. Management theories in favor of greater self-management and self-directed activity cite the importance of autonomy for productivity in the firm and economists in favor of self-management argue that cooperatives are more efficient than centrally-managed firms because every worker receives a portion of the profit, thereby directly tying their productivity to their level of compensation.

Historical economic figures who supported cooperatives and self-management of some kind include the anarchist Pierre Joseph Proudhon, classical economist John Stuart Mill and the neoclassical economist Alfred Marshall. Contemporary proponents of self-management include the American Marxian economist Richard D. Wolff, anarchist philosopher Noam Chomsky and social theorist and sociologist Marcelo Vieta.

Labor managed firm

The theory of the labor manager firm explains the behavior, performance and nature of self-managed organizational forms. Although self-managed (or labor-managed) firms can coincide with worker ownership (employee ownership), the two are distinct concepts and one need not imply the other. According to traditional neoclassical economic theory, in a competitive market economy ownership of capital assets by labor (the workforce of a given firm) should have no significant impact on firm performance.[7]

The classical liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill believed that worker-run and owned cooperatives would eventually displace traditional capitalist (capital-managed) firms in the competitive market economy due to their superior efficiency and stronger incentive structure. While both Mill and Karl Marx thought that democratic worker management would be more efficient in the long run compared with hierarchical management, Marx was not hopeful about the prospects of labor-managed and owned firms as a means to displace traditional capitalist firms in the market economy.[8] Despite their advantages in efficiency, in Western market economies the labor-managed firm is comparatively rare.[9]

Benjamin Ward critiqued the labor managed firm's objective function. According to Ward, the labor-managed firm strives to maximize net income for all its members as contrasted with the traditional capitalist firms' objective function of maximizing profit for external owners. The objective function of the labor managed firm creates an incentive to limit employment in order to boost the net income of the firm's existing members. Thus, an economy consisting of labor-managed firms would have a tendency to underutilize labor and tend toward high rates of unemployment.

Classical economics

In the 19th century, the idea of a self-managed economy was first fully articulated by the anarchist philosopher and economist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.[10] This economic model was called mutualism to highlight the mutual relationship among individuals in this system (in contrast to the parasitism of capitalist society) and involved cooperatives operating in a free-market economy.

The classical liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill argued that worker-run cooperatives would eventually displace traditional capitalist (capital-managed) firms in the competitive market economy due to their superior efficiency.[8]

Karl Marx championed the idea of a free association of producers as a characteristic of communist society, where self-management processes replaced the traditional notion of the centralized state. This concept is related to the Marxist idea of transcending alienation.[11]

Soviet-type economies

The Soviet-type economic model as practiced in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc is criticized by socialists for its lack of widespread self-management and management input on the part of workers in enterprises. However, according to both the Bolshevik view and Marx's own perspective a full transformation of the work process can only occur after technical progress has eliminated dreary and repetitive work, a state of affairs that had not yet been achieved even in the advanced Western economies.[12]

Management science

In his book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us, Daniel H. Pink argues on the basis of empirical evidence that self-management/self-directed processes, mastery, worker autonomy and purpose (defined as intrinsic rewards) are much more effective incentives than monetary gain (extrinsic rewards). According to Pink, for the vast majority of work in the 21st century self-management and related intrinsic incentives are far more crucial than outdated notions of hierarchical management and an overreliance on monetary compensation as reward.

More recent research suggests that incentives and bonuses can have positive effects on performance and autonomous motivation.[13] According to this research, the key is aligning bonuses and incentives to reinforce, rather than hamper, a sense of autonomy, competence and relatedness (the three needs that self determination theory identifies for autonomous motivation).

Political movements

Europe

Worker self-management became a primary component of some trade union organizations, in particular revolutionary syndicalism which was introduced in late 19th century France and guild socialism in early 20th century Britain, although both movements collapsed in the early 1920s. French trade-union CFDT (Confédération Française Démocratique du Travail) included worker self-management in its 1970 program before later abandoning it. The philosophy of workers' self-management has been promoted by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) since its founding in the United States in 1905.

Critics of workers' self-management from the left such as Gilles Dauvé and Jacques Camatte do not admonish the model as reactionary, but simply as not progressive in the context of developed capitalism. Such critics suggest that capitalism is more than a relationship of management. Rather, they suggest capitalism should be considered as a social totality which workers' self-management in and of itself only perpetuates and does not challenge despite its seemingly radical content and activity. This theory is used to explain why self-management in Yugoslavia never advanced beyond the confines of the larger state-monopoly economy, or why many modern worker-owned facilities tend to return to hiring managers and accountants after only a few years of operation.

Guild socialism is a political movement advocating workers' control of industry through the medium of trade-related guilds "in an implied contractual relationship with the public".[14] It originated in the United Kingdom and was at its most influential in the first quarter of the 20th century. It was strongly associated with G. D. H. Cole and influenced by the ideas of William Morris. One significant experiment with workers' self-management took place during the Spanish Revolution (1936–1939).[15] In his book Anarcho-Syndicalism (1938), Rudolf Rocker stated:

But by taking the land and the industrial plants under their own management they have taken the first and most important step on the road to Socialism. Above all, they (the Workers' and peasants self-management) have proved that the workers, even without the capitalists, are able to carry on production and to do it better than a lot of profit-hungry entrepreneurs.[16]

At the height of the Cold War in the 1950s, Yugoslavia advocated what was officially called socialist self-management in distinction from the Eastern Bloc countries, all of which practiced central planning and centralized management of their economies. The economy of Yugoslavia was organized according to the theories of Josip Broz Tito and more directly Edvard Kardelj. Croatian scientist Branko Horvat also made a significant contribution to the theory of workers' self-management (radničko samoupravljanje) as practiced in Yugoslavia. Due to Yugoslavia's neutrality and its leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement, Yugoslav companies exported to both Western and Eastern markets. Yugoslav companies carried out construction of numerous major infrastructural and industrial projects in Africa, Europe and Asia.[17][18]

After May 1968 in France, LIP factory, a clockwork factory based in Besançon, became self-managed starting in 1973 after the management's decision to liquidate it. The LIP experience was an emblematic social conflict of post-1968 in France. CFDT (the CCT as it was referred to in Northern Spain), trade-unionist Charles Piaget led the strike in which workers claimed the means of production. The Unified Socialist Party (PSU) which included former Radical Pierre Mendès-France was in favour of autogestión or self-management.[19]

In the Basque Country of Spain, the Mondragon Cooperative Corporation represents perhaps the longest lasting and most successful example of workers' self-management in the world. It has been touted by a diverse group of people such as the Marxian economist Richard D. Wolff and the research book Capital and the Debt Trap by Claudia Sanchez Bajo and Bruno Roelants[20] as an example of how the economy can be organized on an alternative to the capitalist mode of production.[21]

Following the 2007-2008 financial crisis, a number of factories were occupied and became self-managed in Greece,[22] France,[23] Italy,[24] Germany[25] and Turkey.[26]

North America

During the Great Depression, worker and utility cooperatives flourished to the point that more than half of American farmers belonged to a cooperative. In general, worker cooperatives and cooperative banking institutions were formed across the country and became a thriving alternative for workers and customers.[27][28] Due to the economic downturn and stagnation in the rustbelt, worker cooperatives such as the Evergreen Cooperatives have been formed in response, inspired by Mondragon.

South America

In October 2005, the first Encuentro Latinoamericano de Empresas Recuperadas ("Latin American Encounter of Recovered Companies") took place in Caracas, Venezuela, with representatives of 263 such companies from different countries living through similar economical and social situations. As its main outcome, the meeting had the Compromiso de Caracas ("Caracas' Commitment"), a vindicating text of the movement.

Empresas recuperadas movement

English-language discussions of this phenomenon may employ several different translations of the original Spanish expression other than recovered factory. For example, worker-recuperated enterprise, recuperated/recovered factory/business/company, worker-recovered factory/business, worker-recuperated/recovered company, worker-reclaimed factory, and worker-run factory have been noted.[29] The phenomenon is also known as autogestión,[30] coming from the French and Spanish word for self-management (applied to factories, popular education systems and other uses). Worker self-management may coincide with employee ownership.

Argentina's empresas recuperadas movement emerged in response to the run up and aftershocks of Argentina's 2001 economic crisis[31] and is currently the most significant workers' self-management phenomenon in the world. For various reasons, including broken labour contracts, micro- and macro-economic shocks and crises, rising rates of exploitation at work and threats of or actual unemployment and/or firm closure due to bankruptcy, workers took over control of the factories and shops in which they had been employed, often after a factory occupation to circumvent a lockout.

Empresas recuperadas means "reclaimed/recovered/recuperated enterprises/factories/companies". The Spanish verb recuperar means not only "to get back", "to take back" or "to reclaim", but also "to put back into good condition".[32] Although initially referring to industrial facilities, the term may also apply to businesses other than factories (e.g. Hotel Bauen in Buenos Aires).

Throughout the 1990s in Argentina's southern province of Neuquén, drastic economic and political events occurred where the citizens ultimately rose up. Although the first shift occurred in a single factory, bosses were progressively fired throughout the province so that by 2005 the workers of the province controlled most of the factories.

The movement emerged as a response to the years of crisis leading up to and including Argentina's 2001 economic crisis.[31] By 2001–2002, around 200 Argentine companies were recuperated by their workers and turned into worker co-operatives. Prominent examples include the Brukman factory, the Hotel Bauen and FaSinPat (formerly known as Zanon). As of 2020, around 16,000 Argentine workers run close to 400 recuperated factories.[33]

The phenomenon of empresas recuperadas ("recovered enterprises") is not new in Argentina. Rather, such social movements were completely dismantled during the so-called Dirty War in the 1970s. Thus, during Héctor Cámpora's first months of government (May–July 1973), a rather moderate and left-wing Peronist, approximately 600 social conflicts, strikes and factory occupations had taken place.[34]

Many recuperated factories/enterprises/workplaces are run co-operatively and workers in many of them receive the same wage. Important management decisions are taken democratically by an assembly of all workers, rather than by professional managers.

The proliferation of these "recuperations" has led to the formation of a recuperated factory movement which has ties to a diverse political network including socialists, Peronists, anarchists and communists. Organizationally, this includes two major federations of recovered factories, the larger Movimiento Nacional de Empresas Recuperadas (National Movement of Recuperated Businesses, or MNER) on the left and the smaller National Movement of Recuperated Factories (MNFR)[35] on the right.[36] Some labor unions, unemployed protestors (known as piqueteros), traditional worker cooperatives and a range of political groups have also provided support for these take-overs. In March 2003, with the help of the MNER, former employees of the luxury Hotel Bauen occupied the building and took control of it.

One of the difficulties such a movement faces is its relation towards the classic economic system as most classically managed firms refused for various reasons (among them the ideological hostility and the very principle of autogestión) to work and deal with recovered factories. Thus, isolated recuperated enterprises find it easier to work together in building an alternative, more democratic economic system and manage to reach a critical size and power which enables it to negotiate with the ordinary capitalistic firms.

The movement led in 2011 to a new bankruptcy law that facilitates take over by the workers.[37] The legislation was signed into law by President Cristina Kirchner on June 29, 2011.[38]

See also

- Agile software development

- Anarcho-syndicalism

- Co-determination

- Collectivism

- Consensus decision-making

- Co-operatives

- Council communism

- Democratic socialism

- Employee ownership

- Industrial democracy

- Lean manufacturing

- Libertarian socialism

- Management

- Market socialism

- Mutualism (economic theory)

- Open allocation

- Participatory economics

- Socialization (economics)

- Titoism

- Workers' control

- Workers' council

- Worker cooperative

- Workplace democracy

- Works council

Self-managed organizations

- 1971 Harco work-in, a four-week work-in by Australian steelworkers

- Carlist Party

- Ceylon Transport Board

- Confederación Empresarial de Sociedades Laborales de España

- Corporate Rebels, website on organizational innovation and the future of work

- Economy of Yugoslavia, an economy based on self-managed cooperatives

- Socialist self-management, the form of self-management used in Yugoslavia

- FDSA, Spanish self-managed software programming startup

- Haier Group Corporation, the world's largest self-managed company

- Mondragón Corporation, the world's largest group of industrial cooperative companies

- The Morning Star Company, a fully self-managed private company

- Orpheus Chamber Orchestra

- Paris Commune

- Springfield ReManufacturing

- Unified Socialist Party (France)

- United States Federation of Worker Cooperatives

- W. L. Gore and Associates, one of the oldest, largest and most innovative self-managed companies worldwide

Notes

- Steele, David (1992). From Marx to Mises: Post-Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation. Open Court Publishing Company. p. 323. ISBN 978-0875484495.

The proposal that all the workers in a workplace should be in charge of the management of that workplace has appeared in various forms throughout the history of socialism. [...] [A]mong the labels attached to this form of organization are 'self-management', 'labor management', 'workers' control', 'workplace democracy', 'industrial democracy' and 'producers' cooperatives'.

- Steele, David (1992). From Marx to Mises: Post-Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation. Open Court Publishing Company. p. 323. ISBN 978-0875484495.

The self-management idea has many variants. All the workers may manage together directly, by means of an assembly, or indirectly by electing a supervisory board. They may manage in co-operation with a group of specialized managers or they may do without them.

- O'Hara, Phillip (September 2003). Encyclopedia of Political Economy, Volume 2. Routledge. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-415-24187-8.

In eliminating the domination of capital over labour, firms run by workers eliminate capitalist exploitation and reduce alienation.

- Prychito, David L. (July 31, 2002). Markets, Planning, and Democracy: Essays After the Collapse of Communism. Edward Elgar Pub. p. 71. ISBN 978-1840645194.

The labor-managed firm is a productive organization whose ultimate decision making rights rest in the workers of the firm...In this sense workers’ self-management – as a basic principle – is about establishing control rights within a productive organization, while it leaves open the issue of de jure ownership (that is, who enjoys legal title to the physical and financial assets of the firm) and the type of economic system in which the firm is operating.

- Gregory and Stuart, Paul and Robert (2004). Comparing Economic Systems in the Twenty-First Century, Seventh Edition. George Hoffman. pp. 145–46. ISBN 978-0-618-26181-9.

- Horvat, Branko (1983). The Political Economy of Socialism: A Marxist Social Theory. M.E Sharpe Inc. p. 173. ISBN 978-0873322560.

Participation is not only more desirable, it is also economically more viable than traditional authoritarian management. Econometric measurements indicate that efficiency increases with participation...There is little doubt that the world is moving toward a socialist, self-governing society at an accelerated pace.

- Paul Samuelson, Wages and Interest: A Modern Dissection of Marxian Economic Models, 47 AM.ECON.REV. 884, 894 (1957): "In a perfectly competitive market it really doesn’t matter who hires whom: so have labor hire ‘capital’...”)

- Where Did Mill Go Wrong?: Why the Capital-Managed Firm Rather than the Labor-Managed Enterprise Is the Predominant Organizational Form in Market Economies, by Schwartz, Justin. 2011. Ohio State Law Journal, vol. 73, no. 2, 2012: "Why, then, is the predominant form of industrial organization in market societies the traditional capital-owned and managed firm (the capitalist firm) rather than the labor-managed enterprise owned and managed by the workers (the cooperative)? This is exactly the opposite of the result predicted by John Stuart Mill over 150 years ago. He thought that such worker-run cooperative associations would eventually crowd capitalist firms out of the market because of their superior efficiency and other advantages for workers."

- Where Did Mill Go Wrong?: Why the Capital-Managed Firm Rather than the Labor-Managed Enterprise Is the Predominant Organizational Form in Market Economies, by Schwartz, Justin. 2011. Ohio State Law Journal, vol. 73, no. 2, 2012: "Mill was mistaken, and Marx correct, at least about the tendency for labor-managed firms to displace capital-managed firms in the ordinary operation of the market."

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1866–1876). 'Oeuvres Complètes', volume 17. Paris: Lacroix. pp. 188–89.

- O'Hara, Phillip (September 2003). Encyclopedia of Political Economy, Volume 2. Routledge. p. 836. ISBN 978-0-415-24187-8.

it influenced Marx to champion the ideas of a "free association of producers" and of self-management replacing the centralized state.

- Ellman, Michael (1989). Socialist Planning. Cambridge University Press. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-521-35866-8.

In general, it seems reasonable to say that the state socialist countries have made no progress whatsoever towards organizing the labour process so as to end the division between the scientist and the process workers. This is scarcely surprising, both in view of the Bolshevik attitude toward Taylorism and in view of Marx’s own thesis that a society in which the labour process has been transformed would be one in which technical progress had eliminated dreary, repetitive, work. Such a state of affairs has not yet been reached in even the most advanced countries.

- Gerhart, Barry; Fang, Meiyu (10 April 2015). "Pay, Intrinsic Motivation, Extrinsic Motivation, Performance, and Creativity in the Workplace: Revisiting Long-Held Beliefs". Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. 2 (1): 489–521. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111418.

- "Guild Socialism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 31 May. 2012

- Dolgoff, S. (1974). The Anarchist Collectives: Workers' Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution. ISBN 978-0-914156-03-1.

- Rocker, Rudolf (1938). Anarcho-Syndicalism. p. 69.

- Liotta, P.H. (2001-12-31). "Paradigm Lost :Yugoslav Self-Management and the Economics of Disaster". Balkanologie. Revue d'Études Pluridisciplinaires (Vol. V, n° 1–2). Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- "Yugoslavia: Introduction of Socialist Self-Management". Country Data. December 1990. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- LIP, l'imagination au pouvoir, article by Serge Halimi in Le Monde diplomatique, 20 March 2007 (in French).

- Sanchez Bajo, Claudia; Roelants, Bruno. "Capital and the Debt Trap: learning from cooperatives in the global crisis". Palgrave MacMillan. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- Richard D. Wolff (June 24, 2012). "Yes, there is an alternative to capitalism: Mondragon shows the way." The Guardian. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- "Vio.Me: workers' control in the Greek crisis | workerscontrol.net". www.workerscontrol.net. Retrieved 2020-05-07.

- "Take back the factory: worker control in the current crisis | workerscontrol.net". www.workerscontrol.net. Retrieved 2020-05-07.

- "Occupy, Resist, Produce – Officine Zero | workerscontrol.net". www.workerscontrol.net. Retrieved 2020-05-07.

- "Strike Bike: an occupied factory in Germany | workerscontrol.net". www.workerscontrol.net. Retrieved 2020-05-07.

- "Kazova workers claim historic victory in Turkey | workerscontrol.net". www.workerscontrol.net. Retrieved 2020-05-07.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-01-30. Retrieved 2013-02-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Cooperative Economy in the Great Depression". 2006-05-08.

- Vieta, Marcelo, 2020, Workers' Self-Management in Argentina: Contesting Neo-Liberalism by Occupying Companies, Creating Cooperatives, and Recuperating Autogestión, Brill, Leiden.

- Vieta, Marcelo, 2020, Workers' Self-Management in Argentina: Contesting Neo-Liberalism by Occupying Companies, Creating Cooperatives, and Recuperating Autogestión, Brill, Leiden.

- Guido Galafassi, Paula Lenguita, Robinson Salazar Perez (2004) Nuevas Practicas Politicas Insumisas En Argentina pp. 222, 238.

- Vieta, Marcelo, 2020, Workers' Self-Management in Argentina: Contesting Neo-Liberalism by Occupying Companies, Creating Cooperatives, and Recuperating Autogestión, Brill, Leiden, pp. 517-519.

- Vieta, Marcelo, 2020, Workers' Self-Management in Argentina: Contesting Neo-Liberalism by Occupying Companies, Creating Cooperatives, and Recuperating Autogestión, Brill, Leiden, pp. 517-519.

- Hugo Moreno, Le désastre argentin. Péronisme, politique et violence sociale (1930–2001), Editions Syllepses, Paris, 2005, p. 109 (in French).

- Movimiento Nacional de Fabricas Recuperadas Archived 2007-02-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Marie Trigona, Recuperated Enterprises in Argentina – Reversing the Logic of Capitalism, Znet, March 27, 2006.

- Pagina12: Nueva Ley de Quiebras (April 2011), Fábricas recuperadas y también legales (June 2nd 2011)

- CFK promulgó la reforma de la Ley de Quiebras in Página/12, June 29, 2011

References

- Bolloten, Burnett (1991). The Spanish Civil War: Revolution and Counterrevolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina. ISBN 978-0-8078-1906-7.

- Vieta, Marcelo (2020). Workers' Self-Management in Argentina: Contesting Neo-Liberalism by Occupying Companies, Creating Cooperatives, and Recuperating Autogestión. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-9004268968.

Further reading

- Curl, John. For All The People: Uncovering the Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America, PM Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1-60486-072-6.

- Széll, György. "Workers’ Participation in Yugoslavia." in The Palgrave Handbook of Workers’ Participation at Plant Level (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2019) pp. 167-186.

- Vieta, Marcelo. Workers' Self-Management in Argentina: Contesting Neo-Liberalism by Occupying Companies, Creating Cooperatives, and Recuperating Autogestión , Brill, 2020, ISBN 978-9004268968.

- An Anarchist FAQ, Vol. 2, (2012, AK Press), see section: I.3.2 What is workers' self-management? .

- Anarcho-syndicalism, Rudolf Rocker (1938), AK Press Oakland/Edinburgh. ISBN 978-1-902593-92-0.

- Reinventing Organizations, Frederic Laloux. Nelson Parker, 2014, 378 pp. ISBN 978-2960133509.

Documentary-film

- Living Utopia (original, 1997: Vivir la utopía. El anarquismo en Espana) is a documentary film by Juan Gamero. It consists of 30 interviews with activists of the Spanish Revolution of 1936 and one of the biggest examples of workers' and peasants self-management during the social revolution

External links

- Argentinian workers preparing to defend control of factory, April 26, 2005

- THE NEW RESISTANCE IN ARGENTINA, by Yeidy Rosa

- Self-management and Requirements for Social Property: Lessons from Yugoslavia by Diane Flaherty

- Worker self-management in historical perspective by James Petras and Henry Veltmeyer

- Yugoslavia's Self-Management by Daniel Jakopovich

- Movimiento Nacional de Fabricas Recuperadas (National Movement of Recovered Factories, Spanish only)

- The Worker-Recovered Enterprises in Argentina: The Political and Socioeconomic Challenges of Self-Management Andrés Ruggeri, University of Buenos Aires, Argentina

- Official site for El Cambio Silencioso, book on recovered factories by Esteban Magnani (Spanish and English mostly)

- The Social Innovations of Autogestión in Argentina’s Worker-Recuperated Enterprises: Cooperatively Reorganizing Productive Life in Hard Times (Labor Studies Journal, 2010) by Marcelo Vieta

- Selbsthilfe von Erwerbslosen in Krisenzeiten. Die empresas recuperadas in Argentinien, by Kristina Hille

- Democracy at Work A social movement for a new economy founded by economist Richard D. Wolff

- The End of Illth: In search of an economy that won’t kill us, Harper's Magazine, October 4, 2013

- American Solidarity Party — New 3rd party which favors workers' self-management