Willie Mays

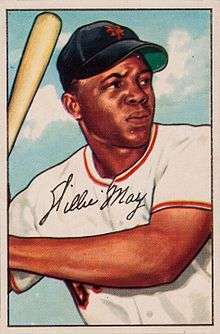

Willie Howard Mays Jr. (born May 6, 1931), nicknamed "The Say Hey Kid", is an American former professional baseball center fielder, who spent almost all of his 22-season Major League Baseball (MLB) career playing for the New York/San Francisco Giants, before finishing with the New York Mets. He is regarded as one of the greatest baseball players of all time and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1979.

| Willie Mays | |||

|---|---|---|---|

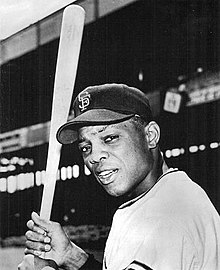

Mays in 1961 | |||

| Center fielder | |||

| Born: May 6, 1931 Westfield, Alabama | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| May 25, 1951, for the New York Giants | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| September 9, 1973, for the New York Mets | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .302 | ||

| Hits | 3,283 | ||

| Home runs | 660 | ||

| Runs batted in | 1,903 | ||

| Stolen bases | 338 | ||

| Teams | |||

| Negro leagues

Major League Baseball | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

| Member of the National | |||

| Induction | 1979 | ||

| Vote | 94.7% (first ballot) | ||

Born in Westfield, Alabama, Mays was raised by his father, Cat, who played baseball in the Birmingham Industrial League. The younger Mays began playing professional baseball in 1948, first with the Chattanooga Choo-Choos, then with the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League. He participated in the 1948 Negro World Series, then was signed by the Giants once he graduated high school in 1950. Mays made his MLB debut in 1951, and after getting only one hit in his first 25 at bats, went on to win the Rookie of the Year Award. Drafted by the United States Army for the Korean War over the offseason, he spent most of the 1952 and 1953 seasons in the military. Returning to the Giants in 1954, Mays was named the National League (NL) Most Valuable Player (MVP) after leading the NL in batting with a .345 batting average. He made one of the most famous plays of all-time in the 1954 World Series when he made an over-the-shoulder catch of a Vic Wertz fly ball to keep the Cleveland Indians from taking the lead in Game 1. The Giants swept the Indians, the lone World Series triumph of Mays's career.

Mays led the NL with 51 home runs in 1955. In 1956, he stole 40 bases, the first of four years in a row he would lead the NL in that category. He won his first of 12 Gold Glove Awards in 1957, a record for outfielders. The Giants moved to San Francisco after the 1957 season, and Mays nearly won the batting title in his first year in the Bay Area, hitting a career-high .347 but losing out to Richie Ashburn on the final day of the season. He batted over .300 for the next two seasons, leading the league in hits in 1960. After leading the NL with 129 runs scored in 1961, Mays led the NL in home runs in 1962 as the Giants won the NL pennant and faced the New York Yankees in the World Series, which the Giants lost in seven games. By 1963, Mays was making over $100,000 a year. In 1964, he was named the captain of the Giants by manager Alvin Dark, leading the NL with 47 home runs that year. He hit 52 the next year, leading the NL and winning his second MVP award. He hit 37 home runs in 1966, the last of 10 seasons in which he had over 100 runs batted in.

Bothered by the flu in 1967, Mays batted .263 with 22 home runs. He batted .289 in 1968 but was moved to the leadoff position in the lineup in 1969 because he was not hitting as many home runs. He hit the 600th of his career that season, though, and he got his 3,000th hit in 1970. In 1971, he reached the playoffs for the first time in nine years as the Giants won the NL West but were eliminated by the Pittsburgh Pirates in the NL Championship Series. Traded to the Mets in 1972, Mays received a standing ovation on his return to New York. The oldest position player in the NL by that year, he spent the rest of 1972 and 1973 with the Mets, playing in the 1973 World Series in his final season. Over his career, he was selected to 24 All-Star Games, the second-most of all-time (tied with Stan Musial, behind Hank Aaron's 25).

Mays finished his career batting 302 with 660 home runs, the fifth-most of all-time, and 1,903 RBI. He holds MLB records for most putouts (7,095) and most extra-inning home runs (22). In 1979, his first year of eligibility, he was elected to the Hall of Fame. Mays had continued to work for the Mets as a hitting instructor, but he was banned from baseball that year by commissioner Bowie Kuhn after accepting a job with a casino, even though the position did not involve Mays actually participating in gambling. The ban lasted six years, before new commissioner Peter Ueberroth listed it in 1985. Mays's number 24 was retired by the Giants in 1972, and the team re-hired him in 1986. In 1993, Mays signed a lifetime contract with the Giants; he currently serves as a Special Assistant to the President and General Manager. Oracle Park, the Giants' home stadium, is located on 24 Willie Mays Plaza.

Considered by many experts, coaches, and fellow players to be one of the greatest players of all-time, Mays was named to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team in 1999 and ranked second on The Sporting News's "List of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players," behind only Babe Ruth. He has been invited to the White House on several occasions and was presented the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015. In 2017, MLB named the World Series Most Valuable Player Award after him. "If somebody came up and hit .450, stole 100 bases and performed a miracle in the field every day, I’d still look you in the eye and say Willie was better," manager Leo Durocher said of him.

Early life

Mays was born in 1931 in Westfield, Alabama, a former primarily black company town near Fairfield.[1][2][lower-alpha 1] His father, Cat Mays, was a talented baseball player with the Negro team for the local iron plant.[3] "They called him 'Cat' because he could run like a cat, very quick," Mays said.[4] His mother, Annie Satterwhite, was a gifted basketball and track star in high school.[5] His parents never married[5] and separated when Mays was three.[6] Mays was raised by his father growing up,[7] as well as two girls named Sarah and Ernestine. James S. Hirsch, who collaborated intensely with Mays when writing his 2010 biography, identifies Sarah and Ernestine as Willie's aunts, his mother's younger sisters; but Mays, in his 1988 autobiography, says they were two orphans from the neighborhood his father took in, whom young Willie saw as his aunts because of their central role in his life.[8][9][10][11] Journalist Allen Barra speculates that it was more likely that Sarah and Ernestine were related to Willie, noting that no explanation has surfaced for how Cat got the authority to move two underage girls into his house.[12] Cat Mays worked as a railway porter when Willie was born, but he later got a job at the steel mills in Westfield so he could be closer to home.[7] Cat exposed Willie to baseball at an early age, playing catch with his son by the time Willie was five.[13] At age 10, Mays was allowed to sit on the bench of his father's games in the Birmingham Industrial League, which Mays remembered as attracting six thousand fans per game at times.[14][15] His favorite baseball player growing up was Joe DiMaggio, but Mays was also a big fan of Ted Williams and Stan Musial.[4]

Mays played multiple sports at Fairfield Industrial High School. On the basketball team, he helped Fairfield Industrial reach a state championship game in 1946 as a sophomore, leading players at Jefferson County all-black high schools in scoring.[16] For the football team, Mays played quarterback, fullback, and punter. His coach, Jim McWilliams, said Mays was "the greatest forward passer I ever saw," and Mays drew comparisons to Harry Gilmer in a local newspaper. One day as a senior, he threw five touchdowns in a 55–0 win over Parker High School.[17] Though he turned 18 in 1949, Mays did not graduate from Fairfield until 1950, which Barra calls "a minor mystery in Willie' life.[18]

Professional baseball

Negro leagues

Mays' professional baseball career began in 1948, while he was still in high school; he played briefly with the Chattanooga Choo-Choos in Tennessee during the summer.[19][20] Later that year, Mays joined the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League. His father had played baseball on an industrial league team with Piper Davis, the Barons' manager, and Davis decided to give Mays an opportunity to play after encountering him while the Black Barons were on road trips in Chattanooga and Atlanta.[21] When E. J. Oliver,[lower-alpha 2] principal at Mays's high school, threatened to suspend Mays for playing professional ball, Davis and Mays's father convinced him that Mays would still be able to concentrate on his studies and worked out an agreement where Mays would only play home games for the Black Barons but in return be allowed to still play football for Fairfield Industrial High School.[23][24] Mays helped Birmingham win the pennant and advance to the 1948 Negro World Series, which they lost 4-1 to the Homestead Grays. Mays hit a respectable .262 for the season, but it was also his excellent fielding and baserunning that made him a standout.[25]

Several Major League Baseball (MLB) teams were interested in signing Mays, but they had to wait until he graduated high school in 1950 to offer him a contract.[18] A number of major league baseball franchises sent scouts to watch him play. The first was the Boston Braves. The scout who discovered him, Bill Maughn, followed him for over a year and inquired of Black Barons owner Tom Hayes about signing him. Hayes wanted $7,500 down and another $7,500 if the Braves kept Mays for at least a year, but Boston chose not to sign him after Hugh Wise, another scout, concluded that Mays was not worth spending $7,500.[26] Maughn then recommended Mays to New York Giants scout Eddie Montague, who was travelling to Birmingham on June 19 to scout Alonzo Perry in a Birmingham doubleheader. Montague was looking for a potential first baseman for the Sioux City Soos of the Class A Western League, and Mays impressed him with his speed, power, and fielding ability.[27][28] After Montague made an enthusiastic report to Giants minor league director Jack Schwarz, Schwarz authorized Montague to sign Mays to a contract. The Brooklyn Dodgers also scouted Mays and wanted Ray Blades to negotiate a deal, but they were too late. On June 4, Montague signed Mays for $4,000.[29]

Minor leagues

Ultimately, Mays never played a game for the Soos. Due to a scandal in Sioux City concerning a Native American's burial in a whites-only cemetery at the time, Sioux City decided not to take Mays, and he was assigned to the Trenton Giants of the Interstate League instead.[30] A Class B team, the Trenton ballclub was in a league with inferior competition to that of the Negro American League. However, the Giants' other Class A affiliate played in the Southern Association, and the Giants feared Mays might be subject to too much racial animosity if he was assigned to that squad. Additionally, Trenton was close enough to New York that it was easier for Giants executives to follow his progress with that team.[31]

After Mays batted .353 in Trenton, he began the 1951 season with the class AAA Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. During his short time span in Minneapolis, Mays played with two other future Hall of Famers: Hoyt Wilhelm and Ray Dandridge. Batting .477 in 35 games and playing excellent defense, Mays was called up to the Giants on May 24, 1951. Mays was at a movie theater in Sioux City, Iowa, when he found out he was being called up. A message flashed up on the screen that said: "WILLIE MAYS CALL YOUR HOTEL."[32][lower-alpha 3] Upon finding out he had been promoted, Mays told his manager, Tommy Heath, to call the Giants and tell them he did not want to get called up, because he did not think he was ready to face major league pitchers. Stunned Giants manager Leo Durocher called him back and convinced him to accept the promotion, saying, "Quit costing the ball club money with long-distance phone calls and join the team."[34] Minneapolis fans were so disappointed about their team losing Mays, Giants owner Horace Stoneham took out a four-column advertisement in the Minneapolis Tribune explaining that Mays's strong play entitled him to a promotion and that New York would keep trying to give Minneapolis players that would help the team win.[35]

Major leagues

Rookie of the Year (1951)

Mays appeared in his first major league game on May 25 against the Philadelphia Phillies at Shibe Park, batting third in the lineup and recording no hits in four at bats.[36] He began his major league career with no hits in his first 12 at bats, but in his 13th on May 28, he hit a towering home run up and over the left field roof of the Polo Grounds off future Hall of Famer Warren Spahn.[37] "For the first sixty feet, it was a helluva pitch," Spahn said.[38] Mays's struggles continued after the home run, which was his only hit in his first 25 at bats, and Durocher dropped him to eighth in the batting order on June 2.[39] He encouraged his young hitter, though, telling Mays, "you're the greatest ballplayer I ever saw or hoped to see" and suggesting that Mays stop trying to pull the ball and just try to make contact.[40] Mays responded with four hits over his next two games on June 2 and June 3, and he pushed his batting average to over .300 by the end of the month.[41]

Wanting to ensure their young new star was cared for in New York, the Giants arranged for Frank Forbes, a local boxing promoter who had represented Sugar Ray Robinson, to make living arrangements for Mays and keep an eye on him.[42] Another mentor for Mays was future Hall of Famer Monte Irvin, his first Giants roommate, who himself had been a Negro Leagues star before joining the Giants.[43] Following Mays's 1-for-25 start, the young star batted close to .290 for the remainder of the season.[44] Although his .274 average, 68 RBI and 20 homers (in 121 games) were among the lowest of his career, he still won the National League (NL) Rookie of the Year Award.[45] During the Giants' comeback in August and September 1951 to tie the Dodgers in the pennant race, Mays' fielding and strong throwing arm were instrumental to several important Giants victories.[46] Mays was in the on-deck circle on October 3 when Bobby Thomson hit the Shot Heard 'Round the World against Ralph Branca and the Brooklyn Dodgers to win the three-game NL tie-breaker series 2-1.[47]

The Giants went on to meet the New York Yankees in the 1951 World Series. In Game 1, Mays, Hank Thompson, and Irvin were the first all-African-American outfield in major league history four years after the color line had been broken.[48] Mays hit poorly while the Giants lost the series 4–2, but he did hit a memorable fly ball in Game 5. DiMaggio and Yankee rookie Mickey Mantle pursued the ball, and as DiMaggio called Mantle off, the younger Yankee got his cleat stuck in an open drainpipe, suffering a knee injury that would affect him the rest of his career.[49] The six-game set was the only time that Mays and DiMaggio (who would retire after the season) would compete against each other.[50][51]

U.S. Army (1952–53)

Soon after the 1951 season ended, Mays discovered he had been drafted by the United States Army to serve in the Korean War. He applied for a 3-A "hardship" exemption, citing 11 dependents he had to take care of. Since Mays did not live with his dependents, however, he was ineligible for the exemption. Mays flunked his aptitude test (he later claimed that he did so on purpose) but passed it on the second opportunity and was slated to report to Camp Kilmer on May 29.[52]

Before Mays left to join the Army, he was able to play the first few weeks of the 1952 season with the Giants. He batted .236 with four home runs in 34 games but surprised sportswiters such as Red Smith when, in his last game before reporting, he drew cheers from fans of the Brooklyn Dodgers, the Giants' archrivals.[53]

After his induction into the Army on May 29 at Camp Kilmer, Mays reported to Fort Eustis, Virginia, where he spent much of his time playing on military baseball teams with other major leaguers, such as future teammate Johnny Antonelli and Vern Law of the Pittsburgh Pirates.[54][55] It was at Fort Eustis that Mays learned the basket catch from a fellow Fort Eustis outfielder, Al Fortunato.[56] On July 25, 1953, he suffered a slight fracture in his left foot when he slid into third base in a game. Durocher was worried when he received the news, but his outfielder made a swift recovery.[57] Mays missed about 266 games due to military service.[56] Discharged on March 1, 1954, Mays reported to Giants' spring training the following day.[58][59]

Most Valuable Player, World Series champion (1954-57)

April 13, 1954, was the first time Mays was in the Giants' lineup on Opening Day; he hit a home run of over 414 feet against Carl Erskine as the Giants defeated the Dodgers 4–3.[60] After he batted .250 in his first 20 games, Durocher moved him from third to fifth in the batting order and encouraged him again to stop trying to pull the ball and instead try to get hits to right field. Mays responded by batting .450 with 25 RBI in his next 20 games.[61] On June 25, he hit an inside-the-park home run against Bob Rush in a 6–2 victory over the Chicago Cubs; the Dodgers announced the accomplishment to their fans in the midst of their own game.[62][63] Mays was selected to the NL All-Star team; he would be a member of the NL All-Star team in 24-straight All-Star games over a span of 20 seasons.[lower-alpha 4][65] Mays became the first player in history to hit 30 home runs before the All-Star Game[66] Mays had 38 home runs through July 28, but around that time, Durocher asked him to stop trying to hit them, explaining that the team wanted him to reach base more so run producers like Irvin, Thompson, or Dusty Rhodes could try to drive him home.[67][68] Mays only hit five home runs after July 8 but upped his batting average from .326 to .345 to win the batting title, becoming the first Giant to lead the league in average since Bill Terry hit .401 in 1930.[68][69] Hitting 41 home runs as well, Mays won the NL Most Valuable Player Award, as well as the Hickok Belt, presented annually to the top professional athlete of the year.[45][70]

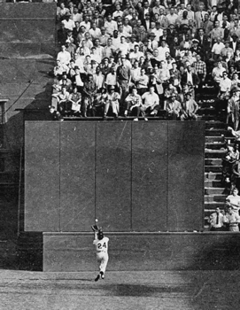

The Giants won the National League pennant and the 1954 World Series, sweeping the Cleveland Indians in four games. The 1954 series is perhaps best remembered for "The Catch", an over-the-shoulder running grab by Mays in deep center field of the Polo Grounds of a long drive off the bat of Vic Wertz during the eighth inning of Game 1. The catch prevented two Indian runners from scoring, preserving a tie game. "The Catch transcended baseball," Barra writes, and Larry Schwartz of ESPN said of all the catches that Mays made, "it is regarded as his greatest."[71][72] Mays did not even look at the ball for the last twenty feet as he ran, saying later that he realized he was going to still be running if he was going to get the ball.[73][74] The Giants won the game in the 10th inning on a three-run home run by Dusty Rhodes, with Mays scoring the winning run.[75] The 1954 World Series was the team's last championship while based in New York. The next time the franchise won was 56 years later when the San Francisco Giants won the World Series in 2010.[76]

During the 1954 offseason, Mays played winter ball for the Cangrejeros de Santurce in Puerto Rico. He batted close to .400 and won the league's MVP award but got into a confrontation with Rubén Gómez on January 11. After Roberto Clemente took a turn at batting practice, Mays was due to hit next, but Gómez tried to go first. When batting practice pitcher Milton Ralat refused to pitch to him, Gómez sat down on home plate. Mays batted anyway with Gómez sitting there and hit a line drive that bounced of Ralat. Ralat cursed Mays, who took a step towards the mound, prompting Gómez to make a move towards Mays while still holding his bat. Mays threw a punch before manager Herman Franks separated the two. Nothing more came of the confrontation, but Mays cut his season short to return to the mainland United States three days later, citing a bruised knee.[77]

Mays went on to perform at a high level each of the last three years the Giants were in New York. He added base stealing to his talents, upping his total from eight in 1954 to 24 in 1955.[78] In the middle of May, Durocher asked him to try for more home runs.[79][80] Mays led the league with 51 but finished fourth in NL MVP voting, behind Roy Campanella, Duke Snider, and Ernie Banks.[78][81] Also leading the league with a .659 slugging percentage, Mays batted .319 as the Giants finished in third.[78] The season ended on a sad note for Mays, as he found out that Durocher would not be managing the Giants in 1956. Durocher gave him the news during the last game of the season against the Philadelphia Phillies. When Mays told him, "But Mr. Leo, it's going to be different with you gone. You won't be here to help me," Durocher responded by telling his star, "Willie Mays doesn't need help from anyone."[82]

In 1956, Mays struggled at first to get along with new manager Bill Rigney, who annoyed Mays by criticizing him publicly (something Durocher never had done).[83] He grew particularly annoyed after a game in St. Louis, in which Rigney fined him $100 for not running to first base on a pop fly that was caught by the catcher.[84] He hit 36 homers and stole 40 bases, being only the second player, and first National League player, to join the "30–30 club".[85] It was his worst season thus far in terms of RBI (84) and batting average (.296), his lowest totals in those categories for nearly a decade; Barra notes, however, that even with the lower totals, "Willie Mays was still the best all-around player in the National League."[86]

The relationship between Mays and Rigney improved in 1957; both Rigney and Mays attributed the reconciliation to Rigney giving Mays less direction, as the new manager obtained more confidence in his star player's ability to succeed on his own.[87] In what Hirsch called "one of his most exhilarating excursions" on April 21, Mays singled against Robin Roberts with one out in the ninth, moved to second on an error, stole third, and scored the winning run on a single, all on close plays requiring him to slide.[88] He stole home in a 4–3 loss to the Cubs on May 21.[89] 1957 was the first season the Gold Glove Awards were presented, and Mays won his first of 12 consecutive for his play in center field. The 1957 one was special because only one outfielder was so honored with an award that year, not three as would be the case in subsequent years.[45][90] At the same time, Mays continued to finish in the National League's top-five in a variety of offensive categories, such as runs scored (112, third) batting average (.333, second), and home runs (35, fourth).[45] In 1957, Mays became the fourth player in major league history to join the 20–20–20 club (2B, 3B, HR), something no player had accomplished since 1941. Mays also stole 38 bases that year, making him the second player in baseball history (after Frank Schulte in 1911) to reach 20 in each of those four categories (doubles, triples, homers, steals) in the same season.[91]

Dwindling attendance and the desire for a new ballpark prompted Stoneham to make the decision to move the Giants to San Francisco after the 1957 season.[92] In the final Giants home game at the Polo Grounds on September 29, 1957, the fans gave Mays a standing ovation in the middle of his final at bat, after Pirates' pitcher Bob Friend had already thrown a pitch to him. "I do not recall hearing another ovation given a man after the pitcher has started to work on him," Mays biographer Arnold Hano wrote.[93] Mays grounded out to short but still drew applause on his way back to the dugout.[93]

Move to San Francisco, 1962 pennant race (1958–1962)

San Francisco welcomed the Giants to town with a parade on April 21, 1958, and Life featured a photo of Mays in the parade a week later.[94] Rigney wanted Mays to challenge Babe Ruth's single-season home run record in 1958; thus, he did not play Mays much in spring training in hopes of using his best hitter every day of the regular season.[95] As he had in 1954, Mays vied for the National League batting title in 1958 until the final game of the season. Moved to the leadoff slot the last day to increase his at bats, Mays collected three hits in the game to finish with a career-high .347, but Philadelphia Phillies' Richie Ashburn won the title with a .350 batting average.[96][97] Mays did manage to share the inaugural NL Player of the Month award with Stan Musial in May (no such award was given out in April until 1969), batting .405 with 12 HR and 29 RBI; he won a second such award in September (.434, 4 HR, 18 RBIs).[98][99] He played all but two games for the Giants, but his 29 home runs were his lowest total since returning from the military.[45]

Stoneham made Mays the highest-paid player in baseball with a $75,000 contract for 1959; Mays would be the highest-paid player through the 1972 season, with the exceptions of 1962 (when he and Mantle tied at $90,000) and 1966 (when Sandy Koufax received more money in his final season).[100] Mays had his first serious injury in 1959, a collision with Sammy White in spring training that resulted in 35 stitches in his leg and two weeks of exhibition ball missed; however, he was ready for the start of the season.[101][102][103] During a series against the Reds in August, Mays also broke a finger but kept it a secret from other teams in order to keep opposing pitchers from throwing at it.[104][105] In September of 1959, the Giants led the NL pennant race by two games with only eight games to play, but a sweep by the Dodgers began a stretch of six losses in those final games, dooming them to fourth.[106] Mays batted .313 with 34 home runs and 113 RBIs, leading the league in stolen bases for the fourth year in a row.[107]

After spending their first two years in San Francisco at Seals Stadium, the Giants moved into the new ballpark that had been built for them, Candlestick Park, in 1960. Initially, the stadium was expected to be conducive to home runs, but tricky winds affected Mays's power, and he hit only 12 at his home ballpark in its first season.[108] He also found the stadium tricky to field at first but developed a strategy to catching fly balls during the season. When a ball was hit, he would count to five before he even started running after it, enabling him to judge how the wind would affect it.[109] He hit two home runs on June 24 and also stole home in a 5–3 victory over the Cincinnati Reds.[110] On September 15, he tied an NL record with three triples in an 11-inning, 8–6 win over the Phillies.[111][112] "I don't like to talk about 1960," Mays said after the final game of a season in which the Giants, preaseason favorites for the pennant, finished fifth out of eight NL teams. "A bad year."[113][114] For the second time in three years, he only hit 29 home runs, but he led the NL with 190 hits and drove in 103 runs, batting .319 and stealing 25 bases.[45]

Alvin Dark was hired to manage the Giants before the start of the 1961 season, and the improving Giants finished 1961 in third place and won 85 games, more than any of their previous six campaigns.[115][116] Mays had one of his best games on April 30, 1961, hitting four home runs and driving in eight runs in a 14–4 win against the Milwaukee Braves at County Stadium. Mays went 4-for-5 at the plate (the only out coming on a fly ball against Moe Drabowsky in the fifth inning), and he was on deck for a chance to hit a record fifth home run when the Giants' half of the ninth inning ended.[117] According to Mays, the four-homer game came after a night in which he got sick eating spareribs; Mays was not even sure he would play the next day until batting practice.[118] Each of his home runs travelled over 400 feet.[119] While Mantle and Roger Maris pursued Babe Ruth's single-season home run record in the AL, Mays and Orlando Cepeda battled for the home run lead in the NL.[120] Mays trailed Cepeda by two home runs at the end of August (34 as opposed to 36), but Cepeda outhit him 10-6 in September to finish with 46, while Mays finished with 40.[121][122] Mays led the league with 129 runs scored and batted .308 with 123 RBI.[45]

Though he had continued to play at a high level since coming to San Francisco, Mays endured booing from the fans through the 1961 season. Barra speculates that this may have been due to San Francisco fans comparing Mays unfavorably to the most famous center fielder ever to come from San Francisco, Joe DiMaggio.[123] Whatever the reason, the boos, which had begun to subside after Mays's four-home run game in 1961, grew even quieter in 1962, as the Giants enjoyed their best season since moving to San Francisco.[124]

Mays led the team in eight offensive categories in 1962: runs (130), doubles (36), home runs (49), RBI (141), stolen bases (18), walks (78), on-base-percentage (.384), and slugging percentage (.613).[125] He finished second in NL MVP voting to Maury Wills, who had broken Ty Cobb's record for stolen bases in a season.[126] On September 30, Mays hit a game-winning home run in the eighth inning against Turk Farrell of the Houston Colt .45's in the Giants' final regularly-scheduled game of the year September 30, forcing the team into a tie for first place with the Los Angeles Dodgers.[127][128] The Giants went on to face the Dodgers in a three-game playoff series, splitting the first two games to force a deciding third at Dodger Stadium. With the Giants trailing 4–2 in the top of the ninth inning, Mays had an RBI single against Ed Roebuck, eventually scoring as the Giants went on to take a 6–4 lead. With two outs in the bottom of the inning, Lee Walls hit a fly ball to center field, which Mays caught for the final out as the Giants advanced to the World Series against the Yankees.[129] Mays had three hits in Game 1 of the World Series, a 6–2 loss to New York, but he would go on to bat .250 in the series.[130] The Series went all the way to a Game 7, which the Yankees led 1–0 in the bottom of the ninth. Matty Alou led off the inning with a bunt single but was still at first two outs later, when Mays came up with the Giants one out from elimination. Batting against Ralph Terry, he hit a ball into the right field corner that might have been deep enough to score Alou, but Giants third base coach Whitey Lockman opted to hold Alou at third. The next batter, McCovey, hit a line drive that was caught by Bobby Richardson, and the Yankees won the deciding game 1–0.[131] It was Mays's last World Series appearance as a member of the Giants.[130] Mays, however, reveled in the fact that he had finally won the support of San Francisco fans; "It only took them five years," he later said.[132]

Highest-paid player, captain, and MVP (1963-66)

Before the 1963 season, Mays signed a contract worth a record-setting $105,000 per season (equivalent to $876,864 in 2019) in the same offseason during which Mantle signed a deal for what would have been a record-tying $100,000 per season.[133] On July 2, when the Giants played the Braves, future Hall of Famers Spahn and Juan Marichal each threw 15 scoreless innings. In the bottom of the 16th inning, Mays hit a home run off Spahn, giving the Giants a 1–0 victory.[134] He considered the home run one of his most important, along with the first one against Spahn and the four he hit in Milwaukee in 1961.[135] He won his third NL Player of the Month Award in August, after batting .387 with eight home runs and 27 RBI.[98][136] The home run total was nearly higher, as one week, Mays hit four balls that landed on top of the centerfield fence at Candlestick Park.[137] He finished the season batting .314 with 38 home runs and 103 RBI. He stole only eight bases, his fewest thefts since the 1954 season.[138]

Normally the third hitter in the lineup, Mays was moved to fourth in the lineup in 1964 before returning to third in subsequent years.[139] On May 21, 1964, Dark named Mays captain of the Giants before a game against the Phillies. "You deserve it," he told Mays. "You should have had it long before this."[140] The move made Mays the first African-American captain of an MLB team.[140] Mays took part in a long game 10 days later when, after playing all nine innings of Game 1 of a doubleheader against the New York Mets, he played all 23 innings of the Giants' 8-6 victory in Game 2.[141] He was moved to shortstop for three innings of the game and grew so tired over the course of it that he used a 31-ounce bat (four ounces smaller than his standard) for his final at bat, in the 23rd inning.[142] Against the Phillies on September 4, he made what Hirsch called "one of the most acrobatic catches of his career."[143] Ruben Amaro, Sr., hit a ball to the scoreboard at Connie Mack Stadium; Mays, who had been playing closer to home plate than normal, had to run at top speed after the ball. He caught the ball midair and had to kick his legs forward to keep his head from hitting the ballpark's fence, but he held on to the ball. The impact forced him to wear a brace temporarily, but Mays only missed one game while recovering.[143] He batted under .300 (.296) for the first time since 1956 but led the NL with 47 home runs (14 more than second-place Billy Williams) and ranked second with 121 runs scored and 111 RBI.[143]

A torn shoulder muscle sustained in a game against Atlanta impaired Mays's ability to throw in 1965. He compensated for this by keeping the injury a secret from opposing players, making two or three practice throws before games to discourage players from running on him.[144] On April 14, against Jim Bunning of the Phillies, he hit his 455th home run, putting him ahead of Mantle in home runs for the first time in his career.[145] On August 22, 1965, Mays and Sandy Koufax acted as peacemakers during a 14-minute brawl between the Giants and Dodgers after Marichal had bloodied Dodgers catcher John Roseboro with a bat.[146] Mays grabbed Roseboro by the waist and helped him off the field, then tackled Lou Johnson to keep him from attacking an umpire.[147] Johnson kicked him in the head and nearly knocked him out. After the brawl, Mays hit a game-winning three-run home run against Koufax, but he did not finish the game, feeling dizzy after the home run.[148][149] Mays also won his fourth and final NL Player of the Month award in August (.363, 17 HR, 29 RBI), while setting the NL record for most home runs in the month of August (since tied by Sammy Sosa in 2001). On September 13, 1965, he hit his 500th career home run off Don Nottebart. Warren Spahn, off whom Mays hit his first career home run, was his teammate at the time. After the home run, Spahn greeted Mays in the dugout, asking "Was it anything like the same feeling?" Mays replied "It was exactly the same feeling. Same pitch, too."[150][lower-alpha 5] The next night, Mays hit one that he considered his most dramatic. With the Giants trailing the Astros by two runs with two outs in the ninth, Mays swung and missed at the first two pitches, took three balls to load the count, and fouled off three pitches before hitting the tying home run off Claude Raymond on the ninth pitch of the at bat. The Giants went on to win 6-5 in 10 innings.[151][152] Mays won his second MVP award in 1965 behind a career-high 52 home runs, in what Barra said "may very well have [been] his best year."[153] He also batted .317, leading the NL in on-base-percentage (.400) and slugging percentage (.645). The span of 11 years between his MVP awards was the longest gap of any major leaguer who attained the distinction more than once, as were the 10 years between his 50 home run seasons.[153][154]

Mays tied Mel Ott's NL record of 511 home runs on April 24, 1966, against the Astros. After that, he went nine days without a home run. "I started thinking home run every time I got up," Mays explained his slump.[155] He finally set the record May 4 with his 512th against Claude Osteen of the Dodgers.[156] Despite nursing an injured thigh muscle on September 7, Mays reached base in the 11th inning of a game against the Dodgers with two outs, then attempted to score from first base on a Frank Johnson single. On a close play, umpire Tony Venzon initially ruled him out, then changed the call when he saw that Roseboro had dropped the ball after Mays collided with him. San Francisco won 3–2.[157][158] In 1966, his last season with 100 RBIs, Mays finished third in the National League MVP voting.[45] It was the ninth and final time he finished in the top five in the voting for the award.[159] Mays batted .288 with 37 home runs and 103 RBI; by season's end, only Babe Ruth had hit more home runs (714 to 542).[160]

Later years with the Giants (1967-72)

Mays had 13 home runs and 44 RBI through his first 75 games of 1967 but went into a slump after that.[161][162] On June 7, Gary Nolan of the Cincinnati Reds struck him out four times in a game; it was the first time in his career that this had happened to Mays (though the Giants won the game 4–3).[161][163] He came down with a fever July 14 and asked manager Franks's permission for the night off but then had to play anyway after Ty Cline, his replacement, hurt himself in the first inning. Mays left the game after the sixth due to fatigue and spent the next five days in a hospital. "After I got back into the lineup, I never felt strong again for the rest of the season," he said.[164][165] In 141 games (his lowest total since returning from the war), Mays hit .263 with 83 runs scored, 128 hits, and 22 home runs. He had only 70 RBI for the year, the first time since 1958 he had failed to reach 100.[45]

"Maybe if I played a little first base in 1968, I could keep from getting tired," Mays speculated in his autobiography, but he only played one game at the position all year.[166][167] In Houston for a series against the Astros May 6, Mays was presented by Astro owner Roy Hofheinz with a 569-pound birthday cake for his 37th birthday—the pounds represented all the home runs Mays had hit in his career. After sharing some of it with his teammates, Mays sent the rest to the Texas Children's Hospital.[168] He played 148 games and upped his batting average to .289, accumulating 84 runs scored, 144 hits, 23 home runs, and 79 RBI.[45]

In 1969, new Giants' manager Clyde King moved Mays to the leadoff position in the batting lineup. King explained to Mays that this was because he was not "hitting home runs like he used to."[169] Mays did not complain about the move in public that year but privately chafed at it, saying in his 1988 autobiography it was like "O. J. Simpson blocking for the fullback."[170] A home plate collision with catcher Randy Hundley on July 29 caused a knee injury that forced Mays to miss several games in August, but he reached a milestone later in the season.[171][172] On September 22, he hit his 600th home run off San Diego's Mike Corkins. He said of the feat, "Winning the game was more important to me than any individual achievements."[173] The knee injury limited him to 117 games, his fewest since he missed the 1953 season.[171] He batted .283 with 13 home runs and 58 RBI.[45]

The Sporting News named Mays as the 1960s "Player of the Decade" in January of 1970. One of baseball's oldest players at the end of the decade, Mays had scored over a thousand runs (1050) and driven in over a thousand runs as well (1003). He had hit 350 home runs, stolen 126 bases, and been named to each All-Star game.[174]

In an April 1970 game against Cincinnati, Mays collided with Bobby Bonds while reaching his glove over the wall but made a catch to rob Bobby Tolan of a home run.[175] Against the Montreal Expos on July 18, Mays picked up his 3,000th hit, a second-inning single against Mike Wegener. The next batter up, McCovey, drove Mays in with a double, and the Giants won 10–1.[176][177] "I don't feel excitement about this now," he told reporters after the game. "The main thing I wanted to do was help Gaylord Perry win a game."[178] In 139 games, Mays batted .291 with 94 runs scored, 28 home runs, and 83 RBI.[178] He scheduled his off days that season to avoid facing pitchers such as Bob Gibson or Tom Seaver.[179]

Mays got off to a fast start in 1971, the year he turned 40.[180] Against the Mets on May 31, he hit a game-tying home run against Jerry Koosman in the eighth inning, made multiple plays at first base that kept runs from scoring as the game progressed into extra innings, and performed a strategic base-running maneuver with one out in the 11th, running slowly from second to third base to draw a throw from Tim Foli and allow Al Gallagher to reach first safely. Evading Foli's tag at first, Mays scored the winning run on Tito Fuentes's sacrifice fly one batter later.[181][182] Mays had 15 home runs and a .290 average at the All-Star break but faded down the stretch, only hitting three home runs and batting .241 for the rest of the year.[180][183] One reason he hit so few home runs was that Mays walked 112 times, 30 more times than he had at any point in his career. This was partly because Willie McCovey, who often batted behind Mays in the lineup, missed several games with injuries, causing pitchers to pitch carefully to Mays so they could concentrate on getting less-skilled hitters out.[184][185] Subsequently, Mays also led the league in on-base percentage (.425) for only the second time in his career.[45] However, his 123 strikeouts were a career-high as well. He batted .271 and stole 23 bases.[180] Though centerfield remained his primary position in 1971, Mays also played 48 games at first base.[45]

The Giants won the NL West in 1971, returning Mays to the playoffs for the first time since 1962.[45][180] "It is just a helpless hurt," he told sportswriter Jimmy Cannon before the series, regarding his age.[186] In the 1971 National League Championship Series (NLCS) against the Pirates, Mays had a home run and three RBI in the first two games.[187] However, the most notable play Mays was involved in occurred in Game 3, when he came to bat in a 1–1 tie in the sixth with no one out and Fuentes on second base. Mays attempted to advance Fuentes to third with a sacrifice bunt, a move that surprised reporters covering the game, as this meant that Mays was willing to allow himself to be called out instead of trying to get a hit in that situation. The bunt failed to advance Fuentes, and the Giants lost 2–1. "I resent anybody saying I'm giving up," Mays told reporters later. "I was thinking of the best way to get the run in," he said, pointing out that McCovey and Bonds were due up next. The Giants lost the series in four games.[188]

By 1972, Mays was the oldest position player in the NL; pitchers Hoyt Wilhelm and Don McMahon were the only players older.[189] Mays got off to a tortuous start to the 1972 season, batting .184 through his first 19 games. Before the season started, he had asked Stoneham for a 10-year contract with the Giants organization, intending to serve in an off-the-field capacity with them once his playing career was over.[190] The Giants organization was in the midst of the financial troubles, however, and Mays had to settled for a two-year contract, though it paid him $165,000 a year.[191][192] Mays quibbled with manager Charlie Fox, leaving the stadium before the start of a doubleheader on April 30 without telling Fox.[193][194] On May 5, Mays was traded to the New York Mets for pitcher Charlie Williams and an undisclosed amount rumored to be $100,000, though the Giants never confirmed this amount. The Mets agreed to keep his salary at $165,000 a year for 1972 and 1973, and Mays stated that they promised to pay him $50,000 a year for 10 years after he retired.[195]

Return to New York: The Mets (1972–73)

Mays had remained popular in New York long after the Giants had left for San Francisco, and the trade was seen as a public relations coup for the Mets. Mets owner Joan Payson, who was a minority shareholder of the Giants when the team was in New York, had long desired to bring Mays back to his baseball roots and was instrumental in making the trade.[196] In his Mets debut on a rainy Sunday afternoon on May 14, Mays put New York ahead to stay with a fifth-inning home run against Don Carrithers and the Giants, receiving ecstatic applause from the fans at Shea Stadium.[197] Mays appeared in 88 games for the Mets in 1972, batting .250 in 244 at bats and hitting eight home runs, as well as 11 doubles.[198]

In 1973, Mays showed up a day late to spring training, then left in the middle of it without notifying manager Yogi Berra beforehand. He was fined $1,000 upon returning; a sportswriter joked that half the fine was for leaving, half was for returning.[199][200] Things did not improve as the season began; Mays spent time on the disabled list early in the year and left the park before a game when he found out Berra had not put his name in the starting lineup. His speed and powerful arm in the outfield, assets throughout his career, were greatly diminished in 1973, and he only made the All-Star team because of a special intervention by NL president Chub Feeney. However, the Mets had a successful season, winning the NL East to guarantee a trip to the playoffs.[201]

On August 17, 1973, in a game against the Reds with Don Gullett on the mound, Mays hit a fourth inning solo home run over the right-center field fence. It was the 660th and final home run of his major league career, and the only run for the Mets in a 2–1 defeat.[202][203] Having considered retirement all year, Mays finally told the Mets officially on September 9 that 1973 would be his last season.[204] He made the announcement to the general public on September 20. "I thought I'd be crying by now," he told reporters and Mets executives at a press conference that day, "but I see so many people here who are my friends, I can't...Baseball and me, we had what you might call a love affair."[205] Five days later, the Mets honored him on Willie Mays Day, proclaimed by New York City mayor John Lindsay, where he thanked the New York fans and said goodbye to baseball.[206] He considered making that his final game, but Payson convinced him to finish out the season.[207] Mays played only 66 games for the Mets that year, batting a career-low .211 with just six home runs.[45]

Against the Reds in the NLCS, Mays did not play until Game 5.[208] Following a brawl started by Pete Rose in Game 1, the Mets fans at Shea Stadium threw trash on the field. After a whiskey bottle almost hit Rose, NL president Feeney threatened to force the Mets to declare a forfeit unless they could calm the fans. Along with three other players and manager Berra, Mays went to left field and settled the fans down. "Look at the scoreboard!" he told them. "We're ahead! Let 'em play the game."[209] In Game 5, he pinch-hit for Ed Kranepool in the fifth inning and had an RBI single against Clay Carroll as the Mets won 7–2, clinching a trip to the 1973 World Series against the Oakland Athletics.[210] A shoulder injury to Rusty Staub prompted the Mets to shift Don Hahn to right field and start Mays in center for the first game of the Series.[211] Leading off Game 1 at the Oakland–Alameda County Coliseum, he had the first hit of the Series, a single against Ken Holtzman. Mays stumbled rounding first base but still made it back safely.[212] In Game 2, he pinch-ran for Staub in the ninth and should have advanced to third on a John Milner single, but he stumbled and had to return to second. He later fell down in the outfield during a play where he was hindered by the glare of the sun and by the hard outfield, an error that allowed the Athletics to tie the game and force extra innings.[213][214] The final hit of his career came later that game, an RBI single against Rollie Fingers that snapped a 7–7 tie in the 12th inning. Mays stumbled on his way to first base but still made it to the base safely, then scored on an error as the Mets prevailed by a score of 10–7.[215][216] His final at bat came on October 16, in Game 3, where he came in as a pinch-hitter for Tug McGraw but grounded into a force play.[130][217] The Mets lost the series in seven games.[218]

All-Star games

Mays's 24 appearances on an All-Star Game roster are tied with Stan Musial for second all-time, behind only Hank Aaron's 25.[219] He "strove for All-Star glory" according to Hirsch, taking the game seriously in his desire to support his teammates and the National League.[220] In the first All-Star Game of 1959, Mays hit a game-winning triple against Ford; Bob Stevens of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote that "Harvey Kuenn gave it honest pursuit, but the only center fielder in baseball who could have caught it hit it."[221][222] He scored the winning run in the bottom of the 10th inning of the first All-Star Game of 1961 on a Clemente single in a 5–4 win for the NL.[223] At Cleveland Stadium in the 1963 All-Star Game, he made the catch of the game, snagging his foot under a wire fence in center field but catching a long fly ball by Joe Pepitone that might have given the AL the lead. The NL won 5–3, and Mays was named the All-Star Game MVP.[224][225] With a leadoff home run against Milt Pappas in the 1965 All-Star Game, Mays set a record for most hits in his All-Star Games (21).[220][226] Mays led off the 1968 All-Star Game with a single, moved to second on an error, advanced to third base on a wild pitch, and scored the only run of the game when McCovey hit into a double play; for his contributions, Mays won the All-Star Game MVP Award for the second time.[227] He individually holds the records for most at bats (75), hits (23), runs scored (20), and stolen bases (six) by an All-Star; additionally, he is tied with Stan Musial for the most extra-base hits (eight) and total bases (40), and he is tied with Brooks Robinson for the most triples (three) in All-Star Game history.[228] In appreciation of his All-Star records, Ted Williams said, "They invented the All-Star Game for Willie Mays."[65] At the 2007 All-Star Game in San Francisco, Mays received a special tribute for his legendary contributions to the game and threw out the ceremonial first pitch.[229]

Barnstorming

During the first part of his career, Mays often participated in barnstorming tours after his regular season with the Giants ended. Teams of star players would travel from city to city playing exhibition games for local fans.[230] Following his rookie year, Mays went on a barnstorming tour with an All-Star team assembled by Campanella, playing in Negro League stadiums around the southern United States.[231] From 1955 through '58, Mays led Willie Mays's All-Stars, a team composed of such stars as Irvin, Thompson, Aaron, Frank Robinson, Junior Gilliam, Brooks Lawrence, Sam Jones, and Joe Black.[232] The team travelled around the southern United States the first two years, attaining crowds of about 5,000 in 1955 but drawing less than 1,000 in 1956, partly because of the advent of television. In 1957, the team went to Mexico, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic, drawing 117,766 fans in 15 games, 14 of which were won by Mays's team. They played 20 games in Mexico in 1958, but Mays did not lead a team in 1959; Stoneham wanted to rest because he was suffering from a broken finger.[232] In 1960, Mays also did not barnstorm, but he and the Giants did go to Tokyo, playing an exhibition season against the Yomiuri Giants.[233] Though teams of black All-Stars assembled those two seasons, they drew fewer fans and opted not to assemble in 1961, when Mays again decided not to barnstorm.[234] The tradition soon died out, as the expansion of the major leagues, the increased televising of major league games, and the emergence of professional football had siphoned interest away from the offseason exhibition games.[230]

Legacy

| |

| Willie Mays's number 24 was retired by the San Francisco Giants in 1972. |

On January 23, 1979, Mays was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. He garnered 409 of the 432 ballots cast (94.68%).[235] Referring to the other 23 voters, acerbic New York Daily News columnist Dick Young wrote, "If Jesus Christ were to show up with his old baseball glove, some guys wouldn't vote for him. He dropped the cross three times, didn't he?"[72] In his induction speech, Mays said, "What can I say? This country is made up of a great many things. You can grow up to be what you want. I chose baseball, and I loved every minute of it. I give you one word—love. It means dedication. You have to sacrifice many things to play baseball. I sacrificed a bad marriage and I sacrificed a good marriage. But I'm here today because baseball is my number one love."[236]

Fellow players and coaches recognized his talent. "To me, Willie Mays is the greatest who ever played," Clemente said.[237] Willie Stargell, Hall of Famer for the Pirates, learned the hard way how good Mays's arm was when the center fielder threw him out in a game in 1965. "I couldn't believe Mays could throw that far. I figured there had to be a relay. Then I found out there wasn't. He's too good for this world."[238] "If somebody came up and hit .450, stole 100 bases and performed a miracle in the field every day, I’d still look you in the eye and say Willie was better," Durocher said.[65] "All I can say is that he is the greatest player I ever saw, bar none," was Rigney's assessment.[54] When Mays was the only player elected to the Hall of Fame in 1979, Snider, who finished second in voting that year and was elected in 1980, said, "Willie really more or less deserves to be in by himself."[239][240] Don Zimmer, a teammate of Mays in Puerto Rico who was involved with professional baseball for 65 years, said, "In the National League in the 1950s, there were two opposing players who stood out over all the others — Stan Musial and Willie Mays. … I’ve always said that Willie Mays was the best player I ever saw. … [H]e could have been an All-Star at any position."[54][241] Teammate Felipe Alou said, "“[Mays] is number one, without a doubt. … [A]nyone who played with him or against him would agree that he is the best.”[54] Al Rosen, All-Star third baseman for Cleveland in the 1950s, said, "From everything I ever witnessed, Mays was the finest player I ever saw. … His presence is electric. … [P]laying against him, you had the feeling you were playing against someone who was going to be the greatest of all time."[54]

Throughout his career, Mays maintained that he did not specifically try to set records, but he ranks among baseball's leaders in many categories.[45][242] Third in home runs with 660 when he retired, he still ranks fifth as of August 2020.[243] His 2,062 runs scored rank seventh, and his 1,903 RBI rank 12th.[45] Mays batted .302 in his career, and his 3,283 hits are the 12th-most of any player.[45] His 2,992 games played are the ninth-highest total of any major leaguer.[45] He also stole 338 bases in his career, leading the NL in steals four years in a row from 1956-59.[45] Hirsch writes that Mays's ability to hit for power and run the bases speedily made him "a new archetype" of player.[244] Mays has the third-highest career power–speed number, behind Barry Bonds and Rickey Henderson, at 447.1.[245][246] By the end of his career, Mays had won a Gold Glove Award 12 times. The total remains a record for outfielders today, shared by Roberto Clemente of the Pirates.[247] He is baseball's all-time leader in outfield putouts (with 7,095), and he played 2,842 games as an outfielder, a total exceeded only by Cobb (2,934) and Barry Bonds (2,874).[45][248]

Mays's career statistics and his longevity in the pre-performance-enhancing drugs era have drawn speculation that he may be the finest five-tool player ever, and many surveys and expert analyses, which have examined Mays' relative performance, have led to a growing opinion that Mays was possibly the greatest all-around offensive baseball player of all time.*[249][250][251][252][253] Jesse Motiff of bleacherreport.com writes, "Willie Mays was the quintessential five-tool player. There was nothing on a baseball diamond that Mays couldn't do."[254] David Schoenfield of ESPN examines the sabermetric statistic runs created, observing Hank Aaron took 13 years to pass Mays's total, which may have been higher had Mays not served in the Army.[255] Schoenfield believes Mays should have won eight MVP awards, and Barra thinks he should have won nine or 10.[256] "He was one of the best fielders of all time," Schoenfield writes, noting that Mays won 12 Gold Glove Awards and has the eighth-most fielding runs saved (a sabermetric stat) of all-time.[255] Barra claimed in 2004, "Most modern fans would pick Willie Mays as the best all-around player in the second half of the twentieth century."[257] Sportscaster Curt Gowdy said of Mays, "Willie Mays was the best player I ever saw. He did everything well."[258]

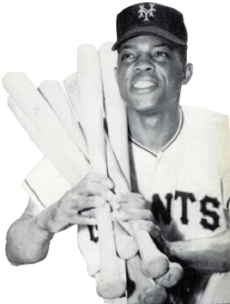

Mays was a popular figure in Harlem, New York's predominantly African-American neighborhood and the home of the Polo Grounds. Magazine photographers were fond of chronicling his participation in local stickball games with kids.[259] In the urban game of hitting a rubber ball with an adapted broomstick handle, Mays could hit a shot that measured "five sewers" (the distance of six consecutive New York City manhole covers, nearly 450 feet).[260] During baseball season, Mays would play the game two to three nights a week.[259] Upon his first marriage in 1956, Mays stopped playing stickball; he later claimed in his 1988 autobiography that he wanted to devote more time to his family.[261][262]

Sudden collapses plagued Mays sporadically throughout his career, which occasionally led to hospital stays. He attributed them to his style of play. "My style was always to go all out, whether I played four innings or nine. That's how I played all my life, and I think that's the reason I would suddenly collapse from exhaustion or nervous energy or whatever it was called."[263]

During his career, Mays would charge a hundred dollars per on-air interview, more than the standard twenty-five dollars at the time. However, he would split the money four ways and give it to the last four players on the Giants' roster.[264]

Amphetamines allegations

At the Pittsburgh drug trials in 1985, former Mets teammate Milner testified that Mays kept a bottle of liquid amphetamine in his locker at Shea Stadium. Milner admitted, however, that he had never seen Mays use amphetamines and Mays himself denied ever having taken any drugs during his career.[265] "I really didn't need anything," Mays said. "My problem was if I could stay on the field. I would go to the doctor and would say to the doctor, 'Hey, I need something to keep me going. Could you give me some sort of vitamin?' I don't know what they put in there, and I never asked him a question about anything."[266] Hirsch wrote "It would be naïve to think Mays never took amphetamines" but also admits that Mays's amphetamine use has never been proven, calling Mays "the most famous player who supposedly took amphetamines."[267]

Post-MLB baseball

After Mays retired as a player, he remained in the New York Mets organization as their hitting instructor until the end of the 1979 season.[268] Mays established a reputation for missing appointments during these years, and he also tended to go home before the start of games. When Joe McDonald became the Mets' General Manager in 1975, he threatened to fire Mays for this; it took the intervention of Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and Mays's lawyer to keep his job. The Mets agreed to keep him but mandated that he stay at home games for at least four innings.[269] Mays did teach the players skills, however; Lee Mazzilli learned the basket catch from him.[270]

In October 1979, Mays took a job at the Park Place Casino (now Bally's Atlantic City) in Atlantic City, New Jersey. While there, he served as a Special Assistant to the Casino's President and as a greeter. After being told by Kuhn that he could not be a coach and baseball goodwill ambassador while at the same time working for Bally's, Mays chose to terminate his contract with the Mets, and he was banned from baseball by Kuhn. Kuhn was concerned about gambling infiltrating baseball, but Hirsch points out that Mays's role was merely as a greeter, he was not allowed to place bets at the casino as part of his contract, and the casino did not engage in sports betting.[271][272] In 1985, less than a year after replacing Kuhn as commissioner, Peter Ueberroth decided to allow Mays and Mantle to return to baseball.[273] Like Mays, Mantle had gone to work for an Atlantic City casino and had been required to give up any baseball positions he held.[274] At a press conference with the pair, Ueberroth said, "I am bringing back two players who are more a part of baseball than perhaps anyone else."[273]

Beginning in 1986, Mays again had a baseball job, as he was named Special Assistant to the President and General Manager of the San Francisco Giants.[275][276] According to Mays, Peter Magowan considered naming him the Giants' manager when he purchased the team after the 1992 season, but Mays was not interested because he had doubts about his ability to succeed in that capacity.[4] He did sign a lifetime contract with the team in 1993 and helped to muster public enthusiasm for building a new stadium in San Francisco, Pac Bell Park, which opened in 2000.[277] Mays has his own charity, the Say Hey Foundation, which promotes youth baseball. In 2009, the foundation donated $50,000 in equipment to young players around the Birmingham area.[278]

Special honors and tributes

Following Mays's MVP season of 1965, Sargent Shriver, head of the United States Job Corps, and Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey asked Mays to speak to kids in the Job Corps. "Willie, the kids will listen to you. All you have to do is talk to them. They look up to you," Humphrey told Mays. Set to go on a nationwide tour, Mays passed out for five to ten minutes just before a meeting in Salt Lake City. He returned to San Francisco to rest, and Lou Johnson (whom he'd battled in a brawl earlier that year) stepped in to take his place.[279][280][281]

Mays' number 24 was retired by the San Francisco Giants in May of 1972, even though Mays was still an active player with the Mets at the time.[282] Oracle Park, the Giants stadium, is located at 24 Willie Mays Plaza. In front of the main entrance to the stadium is a nine-foot tall statue of Mays, and the former star has a private box at the stadium.[277]

During his time with the Giants, Mays became friends with teammate Bobby Bonds, who listed Mays as his favorite player growing up.[4][283] Mays loaned Bonds money to buy a home in San Carlos, California, helped him furnish the house, and allowed him to report late to spring training the year his third child was born.[283] When Bobby's son, Barry, was born, Bobby asked Mays to be Barry's godfather. Mays and the younger Bonds have maintained a close relationship ever since.[4] In 1992, when Barry signed a free agent contract with the Giants, Mays personally offered Bonds his retired #24 (the number Bonds wore in Pittsburgh). Bonds declined, electing to wear #25 instead, which Bobby had worn with the Giants.[284]

Several times, Mays has been an honored guest at the White House. During U.S. President Gerald Ford's administration in 1976, he was invited to the White House state dinner held in honor of Queen Elizabeth II, whom Mays was able to meet.[285] He was the Tee Ball Commissioner at the 2006 White House Tee Ball Initiative on July 30, 2006, during President George W. Bush's administration.[286] On July 14, 2009, he accompanied President Barack Obama to St. Louis aboard Air Force One for the All-Star Game.[287] Six years later, President Obama honored Mays at the White House with the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[288][289] In his remarks as he presented the medal, President Obama said, "Willie also served our country: In his quiet example while excelling on one of America's biggest stages [he] helped carry forward the banner of civil rights...It's because of giants like Willie that someone like me could even think about running for president."[289]

In 1975, Mays received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement[290] In 1999, Mays placed second on The Sporting News's "List of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players", second only to Babe Ruth.[291] Later that year, he was also elected by fans to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.[292] He received the Bobby Bragan Youth Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award in 2005 for his accomplishments on and off the field.[293] On May 15, 2010, Mays was awarded the Major League Baseball Beacon of Life Award prior to MLB's annual Civil Rights Game, held at Great American Ball Park in 2010.[294] In September 2017, Major League Baseball announced its decision to rename the World Series Most Valuable Player Award after Mays, and it has since been referred to as the Willie Mays World Series Most Valuable Player Award.[295]

Though Mays never went to college, he has been presented honorary degrees by several universities. On May 24, 2004, during the 50-year anniversary of The Catch, Mays received an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters degree from Yale University.[296] Dartmouth College also gave him an honorary doctorate.[297] In 2009, he was presented another honorary Doctor of Humane Letters at the commencement ceremony for San Francisco State University.[298]

In 1980, Mays was inducted into the Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame.[299] On December 5, 2007, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver inducted Mays into the California Hall of Fame.[300] He was inducted into the African-American Ethnic Sports Hall of Fame on March 19, 2010.[301]

On June 4, 2008, Community Board 10 in Harlem voted unanimously to give the name "Willie Mays Drive" to an eight-block service road for the Harlem River Drive that runs from 155th Street to 163rd Street, bordering the former location of the Polo Grounds.[302] Willie Mays Parkway and Willie Mays Park in Orlando, Florida were named after Mays in the late 1960s by developers of a neighborhood intended for African-American residents.[303]

Television, film, and music appearances

Mays has made many appearances on television over the years, from appearing in baseball documentaries and on talk shows to acting in sitcoms.[304] He made multiple appearances as the mystery guest on the long-running game show What's My Line?.[305] Through a friendship with Tony Owen and Donna Reed, he was able to appear in three episodes of The Donna Reed Show: "My Son the Catcher" and "Play Ball" (both in 1964, both of which also featured Don Drysdale) and "Calling Willie Mays" (1966).[306][307][308] In 1966, he appeared in the "Twitch or Treat" episode of Bewitched, in which Darrin Stephens asks if Mays is a warlock, and Samantha Stephens replies, "The way he hits? What else?"[309] Judy Pace selected Mays as her date in a 1965 episode of The Dating Game; the two were originally supposed to go to Ankara, but Mays decided after the show that he did not want to go to Turkey, so the pair went to the Bahamas instead.[305] Years after his career ended, in 1989, Mays appeared on My Two Dads in the episode, "You Love Me, Right?"[310]. That same year, he and several other Hall of Famers (Mantle, Banks, Aaron, Harmon Killebrew, Johnny Bench, and Reggie Jackson) made guest appearances in "The Field," an episode of Mr. Belvedere.[311]

NBC-TV aired an hour-long documentary titled A Man Named Mays in 1963, telling the story of the ballplayer's life.[312] In 1972, Mays voiced himself in the animated film Willie Mays and the Say-Hey Kid. The fictional special, produced by Rankin/Bass Productions, features a guardian angel who agrees to help Mays win the NL Pennant if Mays agrees to take care of Veronica, a lonely, mischievous orphan girl. Veronica makes Mays' life difficult, but when relatives show up to claim her after hearing that she's inherited money, Mays' heart softens.[313] Two other films, Major League (1989) and Major League II (1994), include a fictional center fielder for the Cleveland Indians named Willie Mays Hayes.[314][315] Willie Mays Aikens, a real player for the Kansas City Royals born shortly after Mays made "The Catch" in 1954, is not named after Mays.[316]

Mays has been mentioned or referenced in many popular songs. The Treniers recorded the most famous one–"Say Hey (The Willie Mays Song)"–in 1954, with Mays himself participating in the recording.[317] Mays performed the song on episode 4.46 of the Colgate Comedy Hour in 1954.[318] Two others about him were also released in 1954: "Amazing Willie Mays" by the King Odom Quartet and "Say Hey Willie Mays" by the Wanderers.[317] Nine years later, Bob Dylan mentioned him in "I Shall Be Free" from his second studio album, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan.[319] In 1971, Gil Scott-Heron mentioned him in the song, "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised," from the album Pieces of a Man.[320] Terry Cashman's 1981 song "Talkin' Baseball" has the refrain "Willie, Mickey and the Duke," which subsequently became the title of an award given by the New York chapter of the Baseball Writers' Association of America.[321] John Fogerty mentioned Mays, Cobb, and DiMaggio in "Centerfield," the title song from Fogerty's 1985 album.[322] The band Widespread Panic makes reference to Mays in the song "One Arm Steve" from their 1999 album 'Til the Medicine Takes.[323] Mays is also mentioned in "Our Song" by singer-songwriter Joe Henry from the 2007 album Civilians.[324] Chuck Prophet and Kurt Lipschutz (pen name, klipschutz) co-wrote the song "Willie Mays is Up at Bat" for Prophet's 2012 Temple Beautiful album, a tribute to San Francisco.[325]

In 2014, Mays appeared on Calle 13's "Adentro" music video, where he gives René Pérez, the lead singer, a bag containing a pair of sunglasses, a Roberto Clemente baseball uniform, and a baseball bat signed by him. Pérez then used the bat to destroy his luxury car, a Maserati, in an attempt to spread a message to youth about how irresponsible promoting of ostentatious luxury excesses in urban music as a status symbol is inspiring them to kill each other.[326][327]

Mays was mentioned numerous times in Charles M. Schulz's comic strip Peanuts. One of the most famous of these strips was originally published on February 9, 1966. In it, Charlie Brown is competing in a class spelling bee and he is asked to spell the word, "Maze". He erroneously spells it M-A-Y-S and screams out his dismay when he is eliminated. When Charlie Brown is later sent to the principal's office for raising his voice at the teacher, he wonders if one day he will meet Willie Mays and have a good laugh with the ballplayer about the incident.[312]

Personal life

Mays married Marghuerite Wendell Chapman (1926–2010), a woman who had been married twice before, in 1956. Mays said, "We decided to get married so quickly, we had to go to Elkton, Maryland, where you didn't have to wait."[328][329] Forbes tried to talk Mays out of the decision, fearing that Marghuerite was marrying Mays for his money; Willie was so offended at the notion, he cut off his association with his mentor.[330] Willie and Marghuerite adopted a son Michael, five days after he was born in 1959.[328][331] Mays remembered driving Michael around the block as an infant to put him to sleep.[331] The couple separated in 1962, with Marghuerite taking Michael for the majority of the time. They formally divorced in 1963. The divorce hearings often took place the mornings of Giants games, once causing Mays to be late to one.[332] Eight years later, Mays married Mae Louise Allen.[333] Wilt Chamberlain gave Mays her number in 1961, and they had their first date in Pittsburgh when the Giants were in town for a Pirates game. They dated off and on the next several years before Mays finally proposed; they were married in Mexico City over Thanksgiving weekend in 1971.[334] Mae had a graduate degree in social work from Howard University and was employed as a child-welfare worker in San Francisco.[335] In 1997, she was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease; Willie devotedly cared for her throughout her illness.[336] She died of the disease on April 19, 2013.[333] Little is known about Mays's relationship with his adopted son, Michael, but he dedicated his 1966 memoir to him, and following Mays's 3,000th hit in 1971, the Giants presented Michael with a four-year college scholarship.[337][338]

When Mays first joined the Giants, Forbes made arrangements for him to stay with David and Anna Goosby, who lived on St. Nicholas Avenue and 151st Street.[339] "Mrs. Goosby reminded me of my Aunt Sarah, the way she took care of me," Mays said. "Her husband was a kind man who had retired from the railroad. They made me feel at home."[340] Just before his marriage in 1956, he bought a home near Columbia University in Upper Manhattan.[341] When the Giants moved to San Francisco, Mays bought a house in the Sherwood Woods neighborhood adjacent to St. Francis Wood, San Francisco in 1957.[342] However, the purchase was initially met with backlash from neighbors who urged developer Walter Gnesdiloff to reconsider the repercussions "if colored people moved in".[342][343] When mayor George Christopher heard he had been denied housing, he offered to share his house with Mays and his wife until they could get one.[343] Ultimately, Mays and his wife moved into the house in November of 1957, and Mays wrote that when a brick was thrown through the window, "Some neighbors actually called to ask if they could help. So I didn't feel concerned about racial tensions in my neighborhood once the [1958] season was about to start."[344] They only lived there for two years before moving back to New York.[345] However, in 1963, Mays bought a house at 54 Mendosa Avenue in Forest Hill. He was more immediately welcomed in this San Francisco neighborhood, as the homeowners association helped him throw a block party shortly after he moved in.[343] In 1969, he purchased a house in Atherton, California, with financial assistance from his friends Dinah Shore and Reed.[346][133] As of 1987, he owned four houses, and a San Francisco Chronicle article from 2000 reported that Mays still lived in Atherton.[347][348]

Mays took up golf a few years after his promotion to the major leagues and quickly became an accomplished player, playing to a handicap of about nine.[349] "I realized I could use a sport to keep me active once I hung up the glove," Mays said of golf. "I approach it the same way I did baseball. I want to win."[349] He discovered during the 1960s "that people would pay tremendous amounts of money just to play a round of golf with me. And, what the heck, I loved golf."[350] Diagnosed with glaucoma during the 1990s, Mays was forced give up golf, as well as driving, by 2005.[351] A frequent airplane traveler, Mays is one of 66 holders of American Airlines' lifetime passes.[352]

"Say Hey Kid" and other nicknames

It is not clear how Mays became known as the "Say Hey Kid." One story is that in 1951, Barney Kremenko, a writer for the New York Journal, began to refer to Mays as the 'Say Hey Kid' after he overheard Mays use the word "Hey!" repeatedly.[353][354] Another story is that sportswriter Jimmy Cannon created the nickname because Mays did not know everybody's names when he arrived in the minors and would say "Hey!" when he greeted someone. "You see a guy, you say, 'Hey, man. Say hey, man,'" Mays said. "Ted [Williams] was the 'Splinter'. Joe [DiMaggio] was 'Joltin' Joe'. Stan [Musial] was 'The Man'. I guess I hit a few home runs, and they said 'There goes the 'Say Hey Kid.'"[4][355] The nickname led people to believe the phrase "Say hey!" was a common expression of his, when in reality Mays only used the latter of the two words with regularity in his everyday conversations.[353] Before he became known as the "Say Hey Kid", when he began his professional career with the Black Barons, Mays was called "Buck" by teammates and fans.[20] His Trenton teammates called him "Popeye," as his large forearms reminded them of the cartoon character.[355]

See also

- Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame

- 500 home run club

- List of Major League Baseball home run records

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- 3,000 hit club

- 30–30 club

- 20–20–20 club

- 50 home run club

- List of Major League Baseball batting champions

- List of Major League Baseball annual home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual stolen base leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball single-game home run leaders

- Major League Baseball titles leaders

References

- Chambers, Jesse (August 2, 2013). "New film remembers long-gone West Jefferson community of Westfield, home of Mays, Clemon". The Birmingham News. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- Mays, p. 19

- Hirsch, p. 11

- Shea, John (May 3, 2006). "Mays at 75: The Say-Hey Kid has lots of fond memories, few regrets". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- Hirsch, p. 12

- Mays, p. 18

- Mays, pp. 18-25

- Barra, p. 422

- Mays, pp. 18-19

- Freedman, Lew (2007). African American Pioneers of Baseball. Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881: Lew Freedman. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-313-33851-9.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Hirsch, p. 13

- Barra, pp. 22-23

- Hirsch, p. 14

- Mays, pp. 16-17

- Hirsch, p. 15

- Barra, p. 54

- Barra, pp. 49-51

- Barra, p. 101

- Barra, pp. 76-77

- "Willie Mays". Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- Barra, pp. 77-78

- Barra, p. 81

- Mays, p. 32

- Barra, p. 81

- Hirsch, p. 38-48

- Hirsch, p. 58

- Hirsch, p. 59

- Mays, pp. 44-45

- Hirsch, pp. 60-61

- Mays, pp. 45-46

- Hirsch, pp. 65-66

- Hynd, Noel (1988). The Giants of the Polo Grounds. New York: Doubleday. p. 358. ISBN 0-385 23790-1.

- Mays, p. 60

- Barra, pp. 145-46

- Hirsch, p. 79

- Barra, p. 153