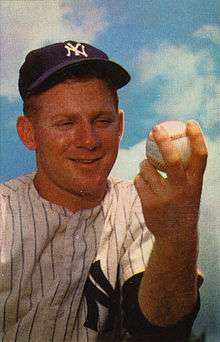

Whitey Ford

Edward Charles "Whitey" Ford (born October 21, 1928),[1] nicknamed "The Chairman of the Board", is an American former professional baseball pitcher who played his entire 16-year Major League Baseball (MLB) career with the New York Yankees. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1974.

| Whitey Ford | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Pitcher | |||

| Born: October 21, 1928 New York City, New York | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| July 1, 1950, for the New York Yankees | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| May 21, 1967, for the New York Yankees | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Win–loss record | 236–106 | ||

| Earned run average | 2.75 | ||

| Strikeouts | 1,956 | ||

| Teams | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

| Member of the National | |||

| Induction | 1974 | ||

| Vote | 77.81% (second ballot) | ||

Ford is a ten-time MLB All-Star and six-time World Series champion. In 1961 Ford won both the Cy Young Award and World Series Most Valuable Player Award. He led the American League in wins three times and in earned run average twice. The Yankees retired Ford's uniform number 16 in his honor on Saturday August 3, 1974.

In the wake of Yogi Berra's death in 2015, George Vecsey, writing in the New York Times, suggested that Ford is now "The Greatest Living Yankee."[2]

Biography

Early life and career

Ford was born in Manhattan (66th St). At age 5, moved to the Astoria (34th Avenue) neighborhood of Queens in New York City, a few miles from the Triborough Bridge to Yankee Stadium in the Bronx.[3] He attended public schools and graduated from the Manhattan High School of Aviation Trades.

Ford was signed by the New York Yankees as an amateur free agent in 1947, and played his entire career with them. While still in the minor leagues, he was nicknamed "Whitey" for his light blond hair.[4]

He began his Major League Baseball career on July 1, 1950 with the Yankees and made a spectacular debut, winning his first nine decisions before losing a game in relief. Ford received a handful of lower-ballot Most Valuable Player votes despite throwing just 112 innings, and was voted the AL Rookie of the Year by the Sporting News. (Walt Dropo was the Rookie of Year choice of the BBWAA.)

In 1951, he married Joan at St. Patrick's Catholic Church in Glen Cove, New York on Long Island. They lived in this city for a period during the 1950s. They had two sons and a daughter together.

During the Korean War era, in 1951 and 1952, Ford served in the Army. He rejoined the Yankees for the 1953 season, and the Yankee "Big Three" pitching staff became a "Big Four", as Ford joined Allie Reynolds, Vic Raschi, and Eddie Lopat.

_In_the_military.jpg)

Pitching career

Ford eventually went from the No. 4 pitcher on a great staff to the universally acclaimed No. 1 pitcher of the Yankees. He became known as the "Chairman of the Board" for his ability to remain calm and in command during high-pressure situations. He was also known as "Slick," a nickname given to him, Billy Martin and Mickey Mantle by manager Casey Stengel, who called them Whiskey Slicks. Ford's guile was necessary because he did not have an overwhelming fastball, but being able to throw several other pitches very well gave him pinpoint control. Ford was an effective strikeout pitcher for his time, tying the then-AL record for six consecutive strikeouts in 1956, and again in 1958. Ford never threw a no-hitter, but he pitched two consecutive one-hit games in 1955 to tie a record held by several pitchers. Sal Maglie, star pitcher for the New York Giants, thought Ford had a similar style to his own, writing in 1958 that Ford had a "good curve, good control, [a] changeup, [and an] occasional sneaky fast ball."[5]

In 1955, Ford led the American League in complete games and games won; in 1956 in earned run average and winning percentage; in 1958, in earned run average; and in both 1961 and 1963, in games won and winning percentage. Ford won the Cy Young Award in 1961; he likely would have won the 1963 AL Cy Young, but this was before the institution of a separate award for each league, and Ford could not match Sandy Koufax's numbers for the Los Angeles Dodgers of the National League. He would also have been a candidate in 1955, but this was before the award was created.

Some of Ford's totals were depressed by Yankees' manager Casey Stengel, who viewed Ford as his top pitching asset and often reserved his ace left-hander for more formidable opponents such as the Tigers, Indians, and White Sox. When Ralph Houk became the manager in 1961, he promised Ford that he would pitch every fourth day, regardless of the opponent; after exceeding 30 starts only once in his nine seasons under Stengel, Ford had 39 in 1961. His first 20-win season, a career-best 25-4 record, and the Cy Young Award ensued, but Ford's season was overshadowed by the home run battle between Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle. As a left-hander with an excellent pick-off move, Ford was also deft at keeping runners at their base: He set a record in 1961 by pitching 243 consecutive innings without allowing a stolen base.

In May 1963, after pitching a shutout, Ford announced he had given up smoking. He said, "My doctor told me that whenever I think of smoking, I should think of a bus starting up and blowing the exhaust in my face."[6]

Career statistics

Ford won 236 games for New York (career 236–106), still a franchise record. Red Ruffing, the previous Yankee record-holder, still leads all Yankee right-handed pitchers, with 231 of his 273 career wins coming with the Yankees. Other Yankee pitchers have had more career wins (for example, Roger Clemens notched his 300th career victory as a Yankee), but amassed them for multiple franchises. David Wells tied Whitey Ford for 13th place in victories by a left-hander on August 26, 2007.

Among pitchers with at least 300 career decisions, Ford ranks first with a winning percentage of .690, the all-time highest percentage in modern baseball history.

During the 16 years that Ford played for the Yankees (1950 and 1953–1967), his .690 winning percentage outpaced that of the Yankees, who had a record of 1,486–1,027 (.594) during the same years, and who were 1,027–106 (.576) for games in which Ford did not earn a decision.

Ford's 2.75 earned run average is the second-lowest among starting pitchers whose careers began after the advent of the live-ball era in 1920. (Only Clayton Kershaw's current 2.51 ERA is lower.) Ford's worst-ever ERA was 3.24. Ford had 45 shutout victories in his career, including eight 1–0 wins.

As a hitter, Ford posted a .173 batting average (177-for-1,023) with 91 runs, 3 home runs, 69 RBI and 113 bases on balls. In 22 World Series games, he batted .082 (4-for-49) with 4 runs, 3 RBI and 7 walks. Defensively, he recorded a .961 fielding percentage.

World Series and All-Star Games

Ford's status on the Yankees was underscored by the World Series. Ford was New York's Game One pitcher in 1955, 1956, 1957, 1958, 1961, 1962, 1963, and 1964. He is the only pitcher to start four consecutive Game Ones, a streak he reached twice. In the 1960 World Series against the Pittsburgh Pirates, Stengel altered this strategy by holding Ford back until Game 3, a decision that angered Ford. The Yankees' ace won both his starts in Games 3 and 6 with complete-game shutouts, but was then unavailable to relieve in the last game of a Yankees loss, the Pirates winning the game — and the Series — on Bill Mazeroski's walk-off home run in the bottom of the ninth. Ford always felt that had he been able to appear in three games instead of just two, the Yankees would have won.

For his career, Ford had 10 World Series victories, more than any other pitcher. Ford also leads all starters in World Series losses (8) and starts (22), as well as innings, hits, walks, and strikeouts. In 1961, he broke Babe Ruth's World Series record of 29⅔ consecutive scoreless innings. The record eventually reached 33⅔, although MLB rule makers retroactively reduced the record to 33 innings since Ford did not complete a full inning before allowing the streak-ending run. It is still a World Series record, although Mariano Rivera broke it as a postseason record in 2000.[7] Ford won the 1961 World Series MVP. In addition to Yankee Stadium, Ford also pitched World Series games in seven other stadiums:

- Ebbets Field (1953 and 1956)

- Milwaukee County Stadium (1957 and 1958)

- Forbes Field (1960)

- Crosley Field (1961)

- Candlestick Park (1962)

- Dodger Stadium (1963)

- Sportsman's Park (1964)

Ford appeared on eight AL All-Star teams between 1954 and 1964.

Retirement

| |

| Whitey Ford's number 16 was retired by the New York Yankees in 1974. |

Ford ended his career in declining health. In August 1966, he underwent surgery to correct a circulatory problem in his throwing shoulder. In May 1967, Ford lasted just one inning in what would be his final start, and he announced his retirement at the end of the month at age 38.

Ford wore number 19 in his rookie season. Following his return from the army in 1953, he wore number 16 for the remainder of his career and it would later be retired by the Yankees on Saturday August 3, 1974.

Ford was a Yankees coach in two different stints: 1968 as first base coach and from 1974-1975, as pitching coach.

After retiring, Ford admitted in interviews to having occasionally doctored baseballs. Examples were the "mudball", used at home in Yankee Stadium. Yankee groundskeepers would wet down an area near the catcher's box where the Yankee catcher Elston Howard was positioned; pretending to lose balance, Howard would put down his hand with the ball and coat one side of the ball with mud and throw it to Ford. Ford sometimes used the diamond in his wedding ring to gouge the ball, but he was eventually caught by an umpire and warned to stop. Howard sharpened a buckle on his shinguard and used it to scuff the ball.

Ford described his illicit behavior as concession to age:

"I didn't begin cheating until late in my career, when I needed something to help me survive. I didn't cheat when I won the twenty-five games in 1961. I don't want anybody to get any ideas and take my Cy Young Award away. And I didn't cheat in 1963 when I won twenty-four games. Well, maybe a little."[8]

Ford admitted to doctoring the ball in the 1961 All Star Game at Candlestick Park to strike out Willie Mays. Ford and Mantle had accumulated $1200 ($10,143 today) in golf pro shop purchases as guests of Horace Stoneham at the Giants owner's country club. Stoneham promised to pay their tab if Ford could strike out Mays. "What was that all about?" Mays asked. "I'm sorry, Willie, but I had to throw you a spitter," Ford replied.[9]

In 1977, Ford was part of the broadcast team for the first game in Toronto Blue Jays history.[10] In 2008, Ford threw the first pitch at the 2008 Major League Baseball All-Star Game. On September 21, 2008 Ford and Yogi Berra were guests of the broadcast team for the final game played at Yankee Stadium.

In 2002, Ford opened "Whitey Ford's Cafe", a sports-themed restaurant and bar next to Roosevelt Field Mall in Garden City, New York.[11] A replica of the Yankee Stadium facade trimmed both the exterior and the bar, whose stools displayed uniform numbers of Yankee luminaries; widescreen TVs were installed throughout. The main dining area housed a panoramic display of Yankee Stadium from the 1950s, specifically a Chicago White Sox–Yankee game with Ford pitching and Mickey Mantle in center field; the Yanks are up 2-0. Waiters and waitresses dressed in Yankees road uniforms, with Ford's retired No. 16 on the back.[12] It lasted less than a year before it closed down.[13]

During the 1950s, Ford lived for a period in Glen Cove, on the North Shore of Long Island. As of 2015, the 86-year-old Ford was splitting his time between his homes in Long Island and Florida.[2]

Representation in other media

- In a 1997 episode of The Simpsons, "The Twisted World of Marge Simpson", an animated Ford is trying to quell a baseball game that is about to turn ugly, "pleading with the crowd for some kind of sanity". He is pummeled by a barrage of pretzels at a baseball game. Homer suggests that the pretzels be rebranded "Whitey Whackers."

- In 1998, Grammy Award-winning musician Everlast scored great success with his CD entitled Whitey Ford Sings the Blues.

- Ford was portrayed by Anthony Michael Hall in the HBO movie, 61* (2001), about Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle's 1961 quest to break Babe Ruth's single-season home run record. It was directed by Billy Crystal.

- He had a cameo appearance on an episode of Remington Steele starring Pierce Brosnan.

Legacy and honors

- 1974, Ford and Mickey Mantle were both elected to baseball's Hall of Fame; at that time, the Yankees retired his number 16.

- 1987, the Yankees dedicated plaques for Monument Park at Yankee Stadium for Ford and Lefty Gomez;

- In 1999, Ford ranked 52nd on The Sporting News List of Baseball's Greatest Players.[14] He was nominated that year for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.

- 2003, Ford was inducted into the Nassau County Sports Hall of Fame.

Place names:

- 1994, a road in Mississauga, Ontario was named Ford Road in his honor. The north-central area of Mississauga is known informally as "the baseball zone", as several streets in the area are named for hall-of-fame baseball players.[15]

See also

- List of Major League Baseball career wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual ERA leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball players who spent their entire career with one franchise

- List of Major League Baseball career strikeout leaders

- TSN Pitcher of the Year (1955, 1961, 1963)

References

- Some sources, such as Retrosheet, claim a 1926 birthdate.

"Whitey Ford". Retrosheet. Retrieved October 22, 2008. - Vecsey, George (September 25, 2015) " Whitey Ford, a Six-Time Champion, Can Add a Title: Greatest Living Yankee", The New York Times, pages B8 and B9

- Berkow, Ira. "ON BASEBALL; Ford Highlight Film Started Early", The New York Times, August 17, 2000. Accessed November 3, 2007. "Vivid in my memory is Stengel's shrug, palms up at his sides, gesturing in response to the mixture of cheers for Ford and boos for his removal. It was a display of sympathy for the kid from Astoria, Queens, who just a few years earlier was playing in street stickball games, and now under a national spotlight and World Series pressure had pitched so beautifully."

- "They Came from Queens", Queens Tribune. Accessed November 4, 2007. "He once lived in Little Neck and attended Aviation High School."

- Terrell, Roy (March 17, 1958). "Part 1: Sal Maglie on the Art of Pitching". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- Ford, Whitey. Slick: My Life In And Around Baseball, New York: William Morrow, 1987.

- Coverdale, Miles, Jr. (2006). Whitey Ford: A Biography. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. p. 155.

- Ford (1987), Slick

- Mays, Willie (1988). Say Hey: The Autobiography of Willie Mays. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 269. ISBN 0671632922.

- Stephen Brunt, Diamond Dreams: 20 Years of Blue Jays Baseball, p. 94, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-023978-2

- Details of Whitey Ford's Cafe from Yahoo! Local.

- Peter M. Gianotti, Review of White Ford's Cafe from Newsday, October 13, 2002.

- Conversation with present owner of Gasho of Japan restaurant, former site of Whitey Ford's Cafe.

- 100 Greatest Baseball Players by The Sporting News : A Legendary List by Baseball Almanac

- google.com

External links

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball-Reference, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- Whitey Ford at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- whiteyford.com Official website

| Sporting positions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Johnny Sain Jim Turner |

New York Yankees pitching coach 1964 1974–1975 |

Succeeded by Cot Deal Cloyd Boyer |

| Preceded by Loren Babe |

New York Yankees first-base coach 1968 |

Succeeded by Elston Howard |