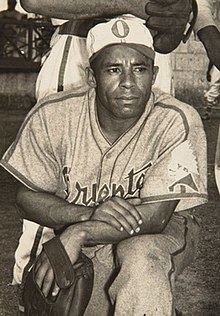

Ray Dandridge

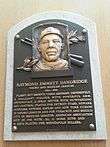

Raymond Emmitt Dandridge (August 31, 1913 – February 12, 1994), nicknamed "Hooks" and "Squat", was an American third baseman in baseball's Negro leagues. Dandridge excelled as a third baseman and he hit for a high batting average. By the time that Major League Baseball was racially integrated, Dandridge was considered too old to play. He worked as a major league scout after his playing career ended. In 1999, Dandridge was inducted into the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame and, late in his life, Dandridge was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1987.

| Ray Dandridge | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Third baseman | |||

| Born: August 31, 1913 Richmond, Virginia | |||

| Died: February 12, 1994 (aged 80) Palm Bay, Florida | |||

| |||

| Negro leagues debut | |||

| 1933, for the Detroit Stars | |||

| Last appearance | |||

| 1955, for the Bismarck Barons | |||

| Teams | |||

| |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

| Member of the National | |||

| Induction | 1987 | ||

| Election Method | Veterans Committee | ||

Early life

Dandridge was born in Richmond, Virginia, to Archie and Alberta Thompson Dandridge.[1]

He played several sports as a child, including baseball, football and boxing. After sustaining a leg injury in football, Dandridge's father made him quit that sport. He focused on baseball, often playing with a bat improvised from a tree branch and a golf ball wrapped in string and tape.[2]

Dandridge lived for a while in Buffalo, New York, before he and his family returned to Richmond.[3] He played baseball locally for teams in Richmond's Church Hill district. Dandridge became known for his short, bowed legs, which later led to nicknames including "Hooks" and "Squat".[1] While playing for a local team in 1933, Dandridge was discovered by Detroit Stars manager Candy Jim Taylor.

Career

He played for the Stars in 1933 and for the Newark Dodgers, which were later called the Newark Eagles, from 1934 to 1938. While with the Eagles, Dandridge was part of the "Million Dollar Infield" that also consisted of Dick Seay, Mule Suttles, and Willie Wells.[4]:p.55

In 1939, badly underpaid by the Eagles, Dandridge moved to the Mexican League, where he played for nine of the next ten seasons, rejoining the Eagles for one last season in 1944. Bill Veeck of the Cleveland Indians called Dandridge in 1947 and asked him to come play in the Cleveland organization. Though that might have given him the chance to be the first black major league player, Dandridge turned it down because he did not want to move his family from Mexico. He also realized that he had been treated well by club owner Jorge Pasquel, who was paying him $10,000 per season plus living expenses.[2]

Pasquel died the next year in a plane crash, prompting Dandridge to return to the United States as a player-manager for the New York Cubans.[2] Although more than capable of playing in the majors, he never got the call to the big leagues, instead spending the last years of his career as the premier player in Triple-A baseball, batting .362 and leading all American Association third basemen in fielding percentage in 1949. He batted .360 in his last minor league season in 1955.

Dandridge was one of the greatest fielders in the history of baseball, and one of the sport's greatest hitters for average. Monte Irvin, who played both in the Negro leagues and the major leagues and saw every great fielding third baseman of two generations, said that Dandridge was the greatest of them all, adding that Dandridge almost never committed more than two errors in a season. Dandridge was also a tutor to the young Willie Mays. Because of the "gentlemen's agreement" not to allow African Americans in Major League Baseball, Dandridge was dismissed as being too old by the time of integration.

Later life

After retiring from playing in 1955, Dandridge worked as a scout for the San Francisco Giants and later ran a recreation center in Newark, New Jersey. He lived his final years in Palm Bay, Florida. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1987. He died at age 80 in Palm Bay.

Dandridge's nephew, Brad Dandridge, played professional baseball[5] from 1993 to 1998, primarily in the Los Angeles Dodgers organization.[6]

References

- Whirty, Ryan (February 18, 2014). "Lost legend". Style Weekly. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- Dawidoff, T. Nicholas (July 6, 1987). "Big call from the Hall". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- "Big Call From The Hall". CNN. 1987-07-06.

- Grigsby, Daryl Russell (2012). Celebrating Ourselves: African-Americans and the Promise of Baseball. Indianapolis: Dog Ear Publishing. ISBN 978-160844-798-5. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- Fatsis, Stephan (1995). Wild and Outside. Walker and Company. p. 248. ISBN 0-8027-7497-0.

- "Brad Dandridge Batting Statistics". Retrieved 2010-02-01.

Further reading

- Dawidoff, Nicholas (July 8, 1987). "Big Call From The Hall: Negro leaguer Ray Dandridge hears from Cooperstown". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 12, 2020 – via si.com/vault.

- Kuenster, John (July 1987). "Willie Mays Recalls Help Ray Dandridge Gave Him in the Long Ago". Baseball Digest. Retrieved June 15, 2009 – via Google Books.

- Langs, Sarah (February 12, 2020). "Ray Dandridge: Best 3B to never make the Majors". MLB.com. Retrieved February 12, 2020.

- Vecsey, George (May 10, 1987). "Sports of the Times; Ray Dandridge, The Hall of Fame and 'Fences'". New York Times. Retrieved June 15, 2009.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- Negro league baseball statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference (Negro leagues)

- BaseballLibrary – biography and career highlights

- BlackBaseball.com: Ray Dandridge

- NegroLeagueBaseball.com: Ray Dandridge