George Brett

George Howard Brett (born May 15, 1953) is an American former professional baseball player who played 21 years, primarily as a third baseman, in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Kansas City Royals.

| George Brett | |||

|---|---|---|---|

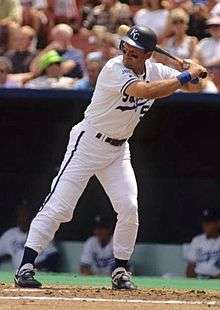

Brett batting in 1990 | |||

| Third baseman / Designated hitter / First baseman | |||

| Born: May 15, 1953 Glen Dale, West Virginia | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| August 2, 1973, for the Kansas City Royals | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| October 3, 1993, for the Kansas City Royals | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .305 | ||

| Hits | 3,154 | ||

| Home runs | 317 | ||

| Runs batted in | 1,596 | ||

| Teams | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

| Member of the National | |||

| Induction | 1999 | ||

| Vote | 98.2% (first ballot) | ||

Brett's 3,154 career hits are second most by any third baseman in major league history (to Adrian Beltre's 3,166) and rank 18th all-time. He is one of four players in MLB history to accumulate 3,000 hits, 300 home runs, and a career .300 batting average (the others being Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, and Stan Musial). He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1999 on the first ballot and is the only player in MLB history to win a batting title in three different decades.

Brett was named the Royals' interim hitting coach in 2013 on May 30, but stepped down from the position on July 25 in order to resume his position of vice president of baseball operations.

Early life

Born in Glen Dale, West Virginia, Brett was the youngest of four sons of a sports-minded family which included Ken, the second oldest, a major league pitcher who pitched in the 1967 World Series at age 19. Brothers John (eldest) and Bobby had brief careers in the minor leagues. Although his three older brothers were born in Brooklyn, George was born in the northern panhandle of West Virginia.

Jack and Ethel Brett then moved the family to the Midwest and three years later to El Segundo, California, a suburb of Los Angeles, just south of LAX. George grew up hoping to follow in the footsteps of his three older brothers. He graduated from El Segundo High School in 1971 and was selected by the Kansas City Royals in the second round (29th overall) of the 1971 baseball draft. He was high school teammates with pitcher Scott McGregor.[1] He lived in Mission Hills, Kansas when he moved to the Midwest.

Playing career

Minor leagues

Brett began his professional baseball career as a shortstop, but had trouble going to his right defensively and was soon shifted to third base. As a third baseman, his powerful arm remained an asset, and he remained at that spot for more than 15 years. Brett's minor league stops were with the Billings Mustangs for the Rookie-level Pioneer League in 1971, the San Jose Bees of the Class A California League in 1972, and the Omaha Royals of the Class AAA American Association in 1973, batting .291, .274, and .284, respectively.

Kansas City Royals (1973–1993)

1973

The Royals promoted Brett to the major leagues on August 2, 1973, when he played in 13 games and was 5 for 40 (.125) at age 20.

1974

Brett won the starting third base job in 1974, but struggled at the plate until he asked for help from Charley Lau, the Royals' batting coach. Spending the All-Star break working together, Lau taught Brett how to protect the entire plate and cover up some holes in his swing that experienced big-league pitchers were exploiting. Armed with this knowledge, Brett developed rapidly as a hitter, and finished the year with a .282 batting average in 113 games.

1975–1979

Brett topped the .300 mark for the first time in 1975, hitting .308 and leading the league in hits and triples.[2] He then won his first batting title in 1976 with a .333 average. The four contenders for the batting title that year were Brett and Royals teammate Hal McRae, and Minnesota Twins teammates Rod Carew and Lyman Bostock. In dramatic fashion, Brett went 2 for 4 in the final game of the season against the Twins, beating out his three rivals, all playing in the same game. His lead over second-place McRae was less than .001. Brett won the title when a fly ball dropped in front of Twins left fielder Steve Brye, bounced on the Royals Stadium AstroTurf and over Brye's head to the wall; Brett circled the bases for an inside-the-park home run. McRae, batting just behind Brett in the line up, grounded out and Brett won his first batting title.

From May 8 through May 13, 1976, Brett had three or more hits in six consecutive games, a major league record. A month later, he was on the cover of Sports Illustrated for a feature article,[2] and made his first of 13 All-Star teams. The Royals won the first of three straight American League West Division titles, beginning a great rivalry with the New York Yankees—whom they faced in the American League Championship Series each of those three years. In the fifth and final game of the 1976 ALCS, Brett hit a three-run homer in the top of the eighth inning to tie the score at six—only to see the Yankees' Chris Chambliss launch a solo shot in the bottom of the ninth to give the Yankees a 7–6 win.[3] Brett finished second in American League MVP voting to Thurman Munson.

A year later, Brett emerged as a power hitter, clubbing 22 home runs, as the Royals headed to another ALCS. In Game 5 of the 1977 ALCS, following an RBI triple, Brett got into an altercation with Graig Nettles which ignited a bench-clearing brawl.

In 1978, Brett batted .294 (the only time between 1976 and 1983 in which he did not bat at least .300) in helping the Royals win a third consecutive AL West title. However, Kansas City once again lost to the Yankees in the ALCS, but not before Brett hit three home runs off Catfish Hunter in Game Three,[4] becoming the second player to hit three home runs in an LCS game (Bob Robertson was the first, having done so in Game two of the 1971 NLCS).

Brett followed with a successful 1979 season, in which he finished third in AL MVP voting. He became the sixth player in league history to have at least 20 doubles, triples and homers all in one season (42–20–23) and led the league in hits, doubles and triples while batting .329, with an on-base percentage of .376 and a slugging percentage of .563.

1980

All these impressive statistics were just a prelude to 1980, when Brett won the American League MVP and batted .390, a modern record for a third baseman. Brett's batting average was at or above .400 as late in the season as September 19, and the country closely followed his quest to bat .400 for an entire season, a feat which has not been accomplished since Ted Williams in 1941.

Brett's 1980 batting average of .390 is second only to Tony Gwynn's 1994 average of .394 (Gwynn played in 110 games and had 419 at-bats in the strike-shortened season, compared to Brett's 449 at bats in 1980) for the highest single season batting average since 1941. Brett also recorded 118 runs batted in, while appearing in just 117 games; it was the first instance of a player averaging one RBI per game (in more than 100 games) since Walt Dropo thirty seasons prior. He led the American League in both slugging and on-base percentage.

Brett started out slowly, hitting only .259 in April. In May, he hit .329 to get his season average to .301. In June, the 27-year-old third baseman hit .472 (17–36) to raise his season average to .337, but played his last game for a month on June 10, not returning to the lineup until after the All-Star Break on July 10.

In July, after being off for a month, he played in 21 games and hit .494 (42–85), raising his season average to .390. Brett started a 30-game hitting streak on July 18, which lasted until he went 0–3 on August 19 (the following night he went 3-for-3). During those 30 games, Brett hit .467 (57–122). His high mark for the season came a week later, when Brett's batting average was at .407 on August 26, after he went 5-for-5 on a Tuesday night in Milwaukee. He batted .430 for the month of August (30 games), and his season average was at .403 with five weeks to go. For the three hot months of June, July, and August 1980, George Brett played in 60 American League games and hit .459 (111–242), most of it after a return from a monthlong injury. For these 60 games he had 69 RBIs and 14 home runs.

Brett missed another 10 days in early September and hit just .290 for the month. His average was at .400 as late as September 19, but he then had a 4 for 27 slump, and the average dipped to .384 on September 27, with a week to play. For the final week, Brett went 10-for-19, which included going 2 for 4 in the final regular season game on October 4. His season average ended up at .390 (175 hits in 449 at-bats = .389755), and he averaged more than one RBI per game. Brett led the league in both on-base percentage (.454) and slugging percentage (.664) on his way to capturing 17 of 28 possible first-place votes in the MVP race.[5] Since Al Simmons also batted .390 in 1931 for the Philadelphia Athletics, the only higher averages subsequent to 1931 were by Ted Williams of the Red Sox (.406 in 1941) and Tony Gwynn of the San Diego Padres (.394 in the strike-shortened 1994 season).

More importantly, the Royals won the American League West, and would face the Eastern champion Yankees in the ALCS.

1980 postseason

During the 1980 post-season, Brett led the Royals to their first American League pennant, sweeping the playoffs in three games from the rival Yankees who had beaten K.C. in the 1976, 1977 and 1978 playoffs. In Game 3, Brett hit a ball well into the third deck of Yankee Stadium off Yankees closer Goose Gossage. Gossage's previous pitch had been timed at 97 mph, leading ABC broadcaster Jim Palmer to say, "I doubt if he threw that ball 97 miles an hour." A moment later Palmer was given the actual reading of 98. "Well, I said it wasn't 97", Palmer replied. Brett then hit .375 in the 1980 World Series, but the Royals lost in six games to the Philadelphia Phillies. During the Series, Brett made headlines after leaving Game 2 in the 6th inning due to hemorrhoid pain. Brett had minor surgery the next day, and in Game 3 returned to hit a home run as the Royals won in 10 innings 4–3. After the game, Brett was famously quoted "...my problems are all behind me".[6] In 1981 he missed two weeks of spring training to have his hemorrhoids removed.[7]

Pine Tar Incident

On July 24, 1983, with the Royals playing against the Yankees at Yankee Stadium, in the top of the ninth inning with two out, Brett hit a go-ahead two-run homer off of Goose Gossage to put the Royals up 5–4. After the home run, Yankees manager Billy Martin cited to the umpires a rule, stating that any foreign substance on a bat could extend no further than 18 inches from the knob. The umpires measured the amount of pine tar, a legal substance used by hitters to improve their grip, on Brett's bat; the pine tar extended about 24 inches. The home plate umpire, Tim McClelland, signaled Brett out, ending the game as a Yankees win. Enraged, Brett charged out of the dugout directly toward McClelland, and had to be physically restrained by two umpires and Royals manager Dick Howser.

The Royals protested the game, and American League president Lee MacPhail upheld the protest, reasoning that the bat should have been excluded from future use, but the home run should not have been nullified. Amid much controversy, the game was resumed on August 18, 1983, from the point of Brett's home run, and ended with a Royals win.

1985

In 1985, Brett had another brilliant season in which he helped propel the Royals to their second American League Championship. He batted .335 with 30 home runs and 112 RBI, finishing in the top 10 of the league in 10 different offensive categories. Defensively, he won his only Gold Glove, which broke Buddy Bell's six-year run of the award, and finished second in American League MVP voting to Don Mattingly. In the final week of the regular season, he went 9-for-20 at the plate with 7 runs, 5 homers, and 9 RBI in six crucial games, five of them victories, as the Royals closed the gap and won the division title at the end. He was MVP of the 1985 playoffs against the Toronto Blue Jays, with an incredible Game 3. With KC down in the series two games to none, Brett went 4-for-4, homering in his first two at bats against Doyle Alexander, and doubled to the same spot in right field in his third at bat, leading the Royals' comeback. Brett then batted .370 in the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, including a four-hit performance in Game 7. The Royals again rallied from a 3–1 deficit to become World Series champions for the first time in Royals history.

1986–1993

In 1988, Brett moved across the diamond to first base in an effort to reduce his chances of injury and had another top-notch season with a .306 average, 24 homers and 104 RBI. But after batting just .290 with 16 homers the next year, it looked like his career might be slowing down. He got off to a terrible start in 1990 and at one point even considered retirement. But his manager, former teammate John Wathan, encouraged him to stick it out. Finally, in July, the slump ended and Brett batted .386 for the rest of the season. In September, he caught Rickey Henderson for the league lead, and in a battle down to the last day of the season, captured his third batting title with a .329 mark. This feat made Brett the only major league player to win batting titles in three different decades.

Brett played three more seasons for the Royals, mostly as their designated hitter, but occasionally filling in for injured teammates at first base. He passed the 3,000-hit mark in 1992, though he was picked off by Angel first baseman Gary Gaetti after stepping off the base to start enjoying the moment. Brett retired after the 1993 season; in his final at-bat, he hit a single up the middle against Rangers closer Tom Henke and scored on a home run by now teammate Gaetti. His last game was also notable as being the final game ever played at Arlington Stadium.

Hall of Fame

Brett was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1999, with what was then the fourth-highest voting percentage in baseball history (98.2%), trailing only Tom Seaver, Nolan Ryan, and Ty Cobb. In 2007, Cal Ripken Jr. passed Brett with 98.5% of the vote. His voting percentage was higher than all-time outfielders Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Stan Musial, Ted Williams, and Joe DiMaggio.

Brett's No. 5 was retired by the Royals on May 14, 1994. His number was the second number retired in Royals history, preceded by former Royals manager, Dick Howser (No. 10), in 1987. It was followed by second baseman and longtime teammate Frank White's No. 20 in 1995.[8]

He was voted the Hometown Hero for the Royals in a two-month fan vote. This was revealed on the night of September 27, 2006 in an hour-long telecast on ESPN. He was one of the few players to receive more than 400,000 votes.[9]

Legacy

| |

| George Brett's number 5 was retired by the Kansas City Royals in 1994. |

His 3,154 career hits are the most by any third baseman in major league history, and 16th all-time. Baseball historian Bill James regards him as the second-best third baseman of all time, trailing only his contemporary, Mike Schmidt. In 1999 he ranked Number 55 on The Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players,[10] and was nominated as a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team. Brett is one of four players in MLB history to accumulate 3,000 hits, 300 home runs, and a career .300 batting average (the others are Stan Musial, Willie Mays, and Hank Aaron). Most indicative of his hitting style, Brett is sixth on the career doubles list, with 665 (trailing Tris Speaker, Pete Rose, Stan Musial, Ty Cobb, and Craig Biggio).

A photo in the July 1976 edition of National Geographic showing Brett signing baseballs for fans with his team's name emblazoned across his shirt was the inspiration for New Zealand singer-songwriter Lorde's 2013 song "Royals," which won the 2014 Grammy Award for Song of the Year.[11] Brett was inducted into the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame in 1994. Brett was inducted into the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame in 2017.[12]

The Mendoza Line

George Brett is credited with coining the term the Mendoza Line. The Mendoza Line, which is used to represent the level of a sub-par batting average (below .200) that is deemed unacceptable at the major league level, is used in reference to Major League shortstop Mario Mendoza. Mendoza was teased for having a mediocre batting average throughout his career in Major League Baseball. Brett referred to the Mendoza Line in an interview with ESPN's Chris Berman which was then expanded into the world of SportsCenter.

Post-baseball activities

Following his playing career, Brett became a vice president of the Royals and has worked as a part-time coach, as a special instructor in spring training, as an interim batting coach, and as a minor league instructor dispatched to help prospects develop. He also runs a baseball equipment and glove company named Brett Bros. with Bobby and, until his death, Ken Brett.[13] He has also lent his name to a restaurant that failed on the Country Club Plaza.

In 1992, Brett married the former Leslie Davenport, and they reside in the Kansas City suburb of Mission Hills, Kansas. The couple has three children: Jackson (named after George's father), Dylan (named after Bob Dylan), and Robin (named after fellow Hall of Famer Robin Yount of the Milwaukee Brewers).[14]

Brett has continued to raise money for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), commonly known as Lou Gehrig's disease. Brett started to raise money for the Keith Worthington Chapter during his playing career in the mid-1980s.

He and his dog Charlie appeared in a PETA ad campaign, encouraging people not to leave their canine companions in the car during hot weather.[15] He also threw out the ceremonial first pitch to Mike Napoli at the 2012 Major League Baseball All-Star Game.

On May 30, 2013, the Royals announced that Brett and Pedro Grifol would serve as batting coaches for the organization. On July 25, 2013 (the day following the 30th anniversary of the "pine tar incident"), the Royals announced that Brett would serve as Vice President, Baseball Operations.

Brett appeared as himself in the ABC sitcom Modern Family on March 28, 2018, alongside co-star Eric Stonestreet, a Kansas City native and Royals fan.[16]

Brett appeared as himself in the Brockmire episode "Player to Be Named Later", in which he is dating Jules (Amanda Peet), much to Brockmire's despair; in the episode "Low and Away", Jules informs Brockmire that she and her now-husband Brett are getting a divorce. Series creator Joel Church-Cooper said in a statement, "When I created a show about a fake Kansas City legend, Jim Brockmire, I thought it only appropriate to have him worship the biggest Kansas City legend of them all -- George Brett."[17]

He is also a recurring guest on the podcast Pardon My Take which is presented by Barstool Sports.

Team ownership

In 1998, an investor group headed by Brett and his older brother, Bobby, made an unsuccessful bid to purchase the Kansas City Royals. Brett is the principal owner of the Tri-City Dust Devils, the Single-A affiliate of the San Diego Padres.[18] He and his brother Bobby also co-own the Rancho Cucamonga Quakes, a Los Angeles Dodgers Single-A partner, and lead ownership groups that control the Spokane Chiefs of the Western Hockey League,[19] the West Coast League's Bellingham Bells, and the High Desert Mavericks of the California League.[20]

See also

- 20–20–20 club

- 3,000 hit club

- List of Major League Baseball players to hit for the cycle

- List of Major League Baseball annual doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball batting champions

- List of Major League Baseball career doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career total bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball doubles records

- List of Major League Baseball hit records

- List of Major League Baseball players who spent their entire career with one franchise

References

- Garrity, Jack (August 17, 1981). "Love and Hate in El Segundo: Jack Brett & his sons". Sports Illustrated: 52.

- Fimrite, Ron (June 21, 1976). "George fills the Royals' flush". Sports Illustrated: 22.

- "1976 American League Championship Series, Game Five". Baseball-Reference.com. October 14, 1976.

- "1978 American League Championship Series, Game Three". Baseball-Reference.com. October 6, 1978.

- Baseball Awards Voting for 1980 Baseball-Reference.com

- "Memories fill Kauffman Stadium". mlb.com. March 5, 2009.

- "Brett in Hospital for Surgery". The New York Times. March 1, 1981.

- Kansas City Royal's. "Kansas City Royal's Retired Numbers". Kansas City Royal's. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- "Brett named Royals Hometown Hero". MLB.com. September 27, 2006.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 12, 2007. Retrieved September 22, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Newell, Sean (December 9, 2013). "This Picture Of George Brett Inspired That Lorde Song "Royals"". Deadspin. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- "See the newest members of the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame". Wichita Eagle. June 7, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- "Our Team". Brett International Sports. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- "Hall of Famer Brett doesn't trust Clemens, upset by 'roids". CNN.

- Conner, Matt (July 25, 2012). "George Brett Teams Up For PETA For Dog Safety Ad". SB Nation Kansas City. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- "Royal visit: George Brett appears Wednesday on 'Modern Family'".

- "Royals Hall of Famer George Brett lands another role as a guest star on TV show".

- "Tri-City Dust Devils: About". Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- "From MLB to CHL – Sportsnet.ca".

- "Brett, brother to buy another team in minors". ESPN.com. March 17, 2009. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

Further reading

- Bondy, Filip (2015). The Pine Tar Game: The Kansas City Royals, the New York Yankees, and Baseball's Most Absurd and Entertaining Controversy. Scribner. ISBN 978-1476777177.

- Brett, George (1999). George Brett: From Here to Cooperstown. Addax Publishing Group. ISBN 1886110794.

- Cameron, Steve (1993). George Brett: Last of a Breed. Taylor. ISBN 0878330798.

- Garrity, John (1981). The George Brett Story. Putnam. ISBN 0698110943.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball-Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet, or Baseball-Almanac.com

| Preceded by Mike Cubbage Gary Redus |

Hitting for the cycle May 28, 1979 July 25, 1990 |

Succeeded by Dan Ford Robby Thompson |