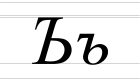

Hard sign

The letter Ъ (italics Ъ, ъ) of the Cyrillic script is known as er golyam (ер голям – "big er") in the Bulgarian alphabet, as the hard sign (Russian: твёрдый знак, romanized: tvjórdyy znak, pronounced [ˈtvʲɵrdɨj ˈznak]), (Rusyn: твердый знак, romanized: tverdyy znak) in the modern Russian and Rusyn alphabets (Although in Rusyn, ъ could also be known as ір), as the debelo jer (дебело їер, "fat er") in pre-reform Serbian orthography,[1] and as ayirish belgisi in the Uzbek Cyrillic alphabet. The letter is called back yer or back jer in the pre-reform Russian orthography, in Old East Slavic, and in Old Church Slavonic. Originally the yer denoted an ultra-short or reduced middle rounded vowel. It is one of two reduced vowels that are collectively known as the yers in Slavic philology.

| Cyrillic letter Yer ъ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Cyrillic script | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Slavic letters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Non-Slavic letters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Archaic letters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bulgarian

In Bulgarian, the er goljam ("ер голям") is the 27th letter of the alphabet. It is used for the phoneme representing the mid back unrounded vowel /ɤ̞/, sometimes also notated as a schwa /ə/. It sounds somewhat like the vowel sound in some pronunciations of English "but" [bʌ̘t] or the Chinese "de" (的) [tɤ]. It is similar to the Romanian letter "ă" (for example, in "băiat" [bəˈjät̪]). In unstressed positions (in the same manner as ⟨а⟩), ⟨ъ⟩ is normally pronounced /ɐ/, which sounds like Sanskrit "a" (अ), Portuguese "terra" [ˈteʁɐ], or the German -er in the word "Kinder" [ˈkʰɪndɐ]. Unlike the schwa sound in English, the Bulgarian /ɤ̞/ can appear in unstressed as well as in stressed syllables, for example in "въ́здух" ['vɤ̞zdux] 'air' or even at the beginning of words (only in the word "ъ́гъл" ['ɤ̞gɐɫ] ‘corner’)

Before the reform of 1945, this sound was written with two letters, "ъ" and "ѫ" ("big yus", denoting a former nasal vowel). Additionally "ъ" was used silently after a final consonant, as in Russian. In 1945 final "ъ" was dropped; and the letter "ѫ" was abolished, being replaced by "ъ" in most cases. However, to prevent confusion with the former silent final "ъ", final "ѫ" was replaced instead with "а" (which has the same sound when not stressed).

It is variously transliterated as ⟨ǎ⟩, ⟨ă⟩, ⟨ą⟩, ⟨ë⟩, ⟨ę⟩, ⟨ų⟩, ⟨ŭ⟩, or simply ⟨a⟩, ⟨u⟩ and even ⟨y⟩.

Belarusian and Ukrainian

The letter is not used in the alphabets of Belarusian and Ukrainian, its functions being performed by the apostrophe. In the Latin Belarusian alphabet (Łacinka), the hard sign's functions are performed by j.

Rusyn

In the Carpatho-Rusyn alphabets of Slovakia and Poland, ъ (Also known as ір) is the last letter of the alphabet, unlike the majority of Cyrillic alphabets, which place ъ after щ. In Pannonian Rusyn, ъ is not present.

Macedonian

Although Macedonian is closely related to Bulgarian, its writing system does not use the yer. During the creation of the modern Macedonian orthography in the late 1944 and the first half of 1945, the yer was one of the subjects of arguments. The problem was that the corresponding vowel exists in many dialects of Macedonian, but it is not systematically present in the west-central dialect, the base on which the Macedonian language standard was being developed.

Among the leaders of the Macedonian alphabet and orthography design team, Venko Markovski argued for using the letter yer, much like the Bulgarian orthography does, but Blaže Koneski was against it. An early version of the alphabet promulgated on December 28, 1944, contained the yer, but in the final version of the alphabet, approved in May 1945, Koneski's point of view prevailed, and no yer was used.[2]

The absence of yer leads to an apostrophe often being used in Macedonian to print texts composed in the language varieties that use the corresponding vowel, such as the Bulgarian writer Konstantin Miladinov's poem Taga za Jug (Тъга за юг).[2]

Russian

Modern Russian: hard sign

In Modern Russian, the letter "ъ" is called the hard sign (твёрдый знак / tvjordyj znak). It has no phonetic value of its own and is purely an orthographic device. Its function is to separate a number of prefixes ending in consonants from subsequent morphemes that begin with iotated vowels. It is therefore commonly seen in front of the letters "я", "е", "ё", and "ю" (ja, je, jo, and ju in English). The hard sign marks the fact that the sound [j] continues to be heard separately in the composition. For example:

- сесть [ˈsʲesʲtʲ] sjestʹ 'sit down'

- встать [vstat'] vstatʹ 'get up'

- съесть [ˈsjesʲtʲ] sʺjestʹ perfective form of 'eat'

It therefore functions as a kind of "separation sign" and has been used only sparingly in the aforementioned cases since the spelling reform of 1918. The consonant before the hard sign often becomes somewhat softened (palatalized) due to the following iotation. As a result, in the twentieth century there were occasional proposals to eliminate the hard sign altogether, and replace it with the soft sign ь, which always marks the softening of a consonant. However, in part because the degree of softening before ъ is not uniform, the proposals were never implemented. The hard sign ъ is written after both native and borrowed prefixes. It is sometimes used before "и" (i), non-iotated vowels or even consonants in Russian transcriptions of foreign names to mark an unexpected syllable break, much like an apostrophe in Latin script (e.g. Чанъань — Chang'an), the Arabic ʽayn (e.g. Даръа — Darʽa [ˈdarʕa]), or combined with a consonant to form a Khoisan click (e.g. Чъхоан — ǂHoan). However, such usage is not uniform and, except for transliteration of Chinese proper names, has not yet been formally codified (see also Russian phonology and Russian orthography).

Final yer pre-1918

Before 1918, a hard sign was normally written at the end of a word when following a non-palatal consonant, even though it had no effect on pronunciation. For example, the word for "cat" was written "котъ" (kot') before the reform, and "кот" (kot) after it. This old usage of ъ was eliminated by the spelling reform of 1918, implemented by the Bolshevik regime after the 1917 October Revolution. Because of the way this reform was implemented, the issue became politicized, leading to a number of printing houses in Petrograd refusing to follow the new rules. To force the printing houses to comply, red sailors of the Baltic Fleet confiscated type carrying the "parasite letters".[3][4] Printers were forced to use a non-standard apostrophe for the separating hard sign, for example:

- pre-reform: съѣздъ

- transitional: с’езд

- post-reform: съезд

In the beginning of the 1920s, the hard sign was gradually restored as the separator. The apostrophe was still used afterward on some typewriters that did not include the hard sign, which became the rarest letter in Russian. In Belarusian and Ukrainian, the hard sign was never brought back, and the apostrophe is still in use today.

According to the rough estimation presented in Lev Uspensky's popular linguistics book A Word On Words (Слово о словах / Slovo o slovah), which expresses strong support for the reform, the final hard sign occupied about 3.5% of the printed texts and essentially wasted a considerable amount of paper, which provided the economic grounds to the reform.

Printing houses set up by Russian émigrés abroad kept using the pre-reform orthography for some time, but gradually they adopted the new spelling. Meanwhile in the USSR, Dahl’s Explanatory Dictionary was repeatedly (1935, 1955) reprinted in compliance with the old rules of spelling and the pre-reform alphabet.

Today the final yer is sometimes used in Russian brand names: the newspaper Kommersant (Коммерсантъ) uses the letter to emphasize its continuity with the pre-Soviet newspaper of the same name. Such usage is often inconsistent, as the copywriters may apply the simple rule of putting the hard sign after a consonant at the end of a word but ignore the other former spelling rules, such as the use of ѣ and і.[5] It is also sometimes encountered in humorous personal writing adding to the text an "old-fashioned flavour" or separately, denoting true.

Languages of the Caucasus and Crimean Tatar

In Cyrillic orthographies for various languages of the Caucasus, along with the soft sign and the palochka, the hard sign is a modifier letter, used extensively in forming digraphs and trigraphs designating sounds alien in Slavic, such as /q/ and ejectives. For example, in Ossetian, the hard sign is part of the digraphs гъ /ʁ/, къ /kʼ/, пъ /pʼ/, тъ /tʼ/, хъ /q/, цъ /tsʼ/, чъ /tʃʼ/, as well as the trigraphs къу /kʷʼ/ and хъу /qʷ/. The hard sign is used in the Crimean Tatar language for the same purpose.

Related letters and other similar characters

- Ь ь : Cyrillic letter soft sign

- Ӏ ӏ : Cyrillic letter Palochka

- Ҍ ҍ : Cyrillic letter semisoft sign

- Ѣ ѣ : Cyrillic letter yat

- Ƅ ƅ : Latin letter tone 6

Computing codes

| Preview | Ъ | ъ | ᲆ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER HARD SIGN | CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER HARD SIGN | CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TALL HARD SIGN | |||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | decimal | hex | decimal | hex |

| Unicode | 1066 | U+042A | 1098 | U+044A | 7302 | U+1C86 |

| UTF-8 | 208 170 | D0 AA | 209 138 | D1 8A | 225 178 134 | E1 B2 86 |

| Numeric character reference | Ъ | Ъ | ъ | ъ | ᲆ | ᲆ |

| Named character reference | Ъ | ъ | ||||

| KOI8-R and KOI8-U | 255 | FF | 223 | DF | ||

| Code page 855 | 159 | 9F | 158 | 9E | ||

| Code page 866 | 154 | 9A | 234 | EA | ||

| Windows-1251 | 218 | DA | 250 | FA | ||

| Macintosh Cyrillic | 154 | 9A | 250 | FA | ||

References

- Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, Pismenica serbskoga iezika, po govoru prostoga naroda, 1814.

- Dontchev Daskalov, Roumen; Marinov, Tchavdar (2013), Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies, Balkan Studies Library, BRILL, pp. 453–456, ISBN 900425076X

- ""Лексикон" Валерия Скорбилина Архив выпусков программы, "ЛЕКСИКОН" № 238, интервью с Натальей Юдиной, деканом факультета русского языка и литературы". Archived from the original on 2009-06-04. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- Слово о словах, Лев Успенский, Лениздат, 1962, p. 156

- Артемий Лебедев, Ководство, § 23. Немного о дореволюционной орфографии.

External links