Old Montreal

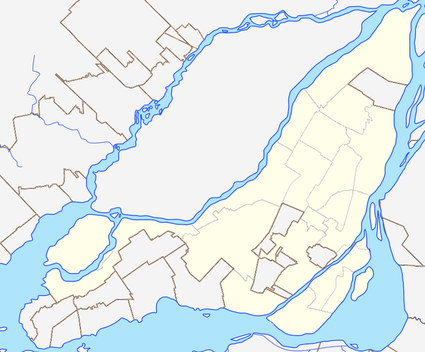

Old Montreal (French: Vieux-Montréal) is a historic neighbourhood within the municipality of Montreal in the province of Quebec, Canada. Founded by French settlers in 1642 as Fort Ville-Marie, Old Montreal is home to many structures dating back to the era of New France.[2] The 17th century settlement lends its name to the borough in which the neighbourhood lies, Ville-Marie. Home to the Old Port of Montreal, the neighbourhood is bordered on the west by McGill Street, on the north by Ruelle des Fortifications, on the east by rue Saint-André, and on the south by the Saint Lawrence River. Following recent amendments, the neighbourhood has expanded to include the Rue des Soeurs Grises in the west, Saint Antoine Street in the north, and Saint Hubert Street in the east. In 1964, much of Old Montreal was declared a historic district by the Ministère des Affaires culturelles du Québec.[2]

Old Montreal | |

|---|---|

| Vieux-Montréal | |

.jpg) View of Old Montreal from the Old Port of Montreal | |

Old Montreal Location of Old Montreal in Montreal | |

| Coordinates: 45°30′18″N 73°33′18″W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Quebec |

| City | Montreal |

| Borough | Ville-Marie |

| Area | |

| • Land | 0.71 km2 (0.27 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 4,531 |

| • Density | 6,381.7/km2 (16,529/sq mi) |

| • Change (2006-11) | |

| • Dwellings | 3,312 |

Patrimoine culturel du Québec | |

| Official name | Site patrimonial de Montréal |

| Type | Site patrimonial déclaré |

| Designated | 1964-01-08 |

| Reference no. | 93528 |

History

Early French settlement

In 1605, Samuel de Champlain established a fur-trading post at Place Royale (Old Montreal) at the confluence of the Saint Lawrence River and the Petite Rivière St-Pierre, a former river in the area. It was adjacent to present-day Place D'Youville and the Pointe-à-Callière Museum. However, the settlers were later forced to abandon the outpost due to incursions by the Iroquois.

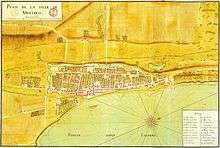

The original settlement of Montreal was founded in 1642. It was known as Ville-Marie, and was located in roughly the same location as the trading post set up by de Champlain. The founder, Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve, built a fort in 1643 which would serve as the headquarters for the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, an organization whose mission was to convert members of First Nations to Christianity and establish a Christian settlement in New France. The company in charge of managing the settlement was founded by the Sulpician Jean-Jacques Olier and by Jérôme Le Royer (Sieur de La Dauversière).

French colony

After the Société Notre-Dame dissolved on March 9, 1663,[3] the Sulpicians (who arrived in 1657) became the Seigneurs of Montreal, as King Louis XIV of France took personal control over the colony. The new system gave them the island of Montreal, with the obligation to live there and ensure its development by cultivating the land. In 1665, Louis XIV sent 1,200 men from the Régiment de Carignan-Salières. The Sulpicians organized seigneuries at the center of the island. François Dollier Casson established the first grid of streets in the colony, following the paths of existing trails. These early streets included the Rue Notre-Dame, the Rue Saint-Paul and Rue Saint-Jacques. Buildings of the era include the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal, the Saint-Sulpice Old Seminary and Notre Dame Church (replaced later by the Notre-Dame Basilica).

In the early 18th century, the name "Montreal" (which originally referred to the mountain Mont-Royal) gradually replaced that of Ville-Marie. The arrival in 1657 of Marguerite Bourgeoys (who founded the Congregation Notre-Dame) and the arrival of the Jesuits and Recollets in 1692, helped to ensure the Catholic character of the settlement. The original fortifications of Montreal, erected in 1717 by Gaspard Chaussegros de Léry, formed the boundaries of Montreal at the time. De Léry had the fortifications constructed to secure the settlement from a British invasion and to allow future expansion inside the walls. Though the walls may have provided security from invasion, they created a different problem: a large concentration of wooden houses (with fireplaces) led to many devastating fires. In 1721, Montreal received a royal order from France to ban wood construction; buildings were to be constructed using stone, but the ban was never fully respected.

British control

Canada (New France) became a British colony in 1763 after the Seven Years' War. British rule radically changed the face of Old Montreal, partially due to significant fires that destroyed much of the city and provided the British with a mandate to rebuild it. In May 1765, fire destroyed about 110 houses before destroying the old Hôtel de Callière and the former General Hospital. In April 1768, 88 houses between rue Saint-Jean-Baptiste and Hotel Vaudreuil were burned, including the Congregation Notre-Dame convent. Between the two fires, nearly half of the buildings in the city were destroyed. In the following years, the city was rebuilt even more densely. On June 6, 1803, a massive fire destroyed the prison, the church and the dependencies of Jesuits, a dozen houses and the Château Vaudreuil. Two speculators bought the Château's gardens, offered one-third to the city, and divided the rest into seven lots of their own. The city's oldest public monument, Nelson's Column,[4] was erected in 1809 on part of the former garden plot and given to the city. This space became the new market square, called Marché Neuf (New Market) before assuming its present name of Place Jacques-Cartier in 1845. The space occupied by the church of the Jesuits became the Place Vauquelin and Montreal City Hall arose from the old Jesuit gardens in 1873.

In 1812, a fire destroyed the luxurious Mansion House hotel, which had been popular with the Beaver Club and had housed the first public library in Montreal. It was replaced by the British-American Hotel, which contained the John Molson-built Royal Theatre, the city's first permanent theatre. The hotel burned in 1833, and was rebuilt in 1845 at the Bonsecours Market. In 1849, a riot caused a fire with political consequences when, protesting against a law, a Tory crowd burned down the Parliament building in the old Marché Saint-Anne on Place d'Youville. The site of the Parliament fire housed Montreal's first fire station in 1903; the building still exists as the Centre d’histoire de Montréal.

Colonial authorities decided upon the first radical transformation of the area in 1804, with the destruction of the fortifications surrounding the heart of Montreal. Completed in 1815, this enlarged the perimeter of Old Montreal and improved access to suburban communities. The 19th century witnessed the emergence of a bourgeoisie of mostly Scottish merchants. The growing activity of the port changed the urban landscape. Old Montreal became less residential, as the rich Scottish and English merchants built extravagant homes closer to Mount Royal (in what would become the Golden Square Mile). Anglophone influence became the dominating force in the areas of banking, manufacturing, commerce, and finance. St. James Street became the financial centre of Montreal, with large banks such as the Bank of Montreal and the Royal Bank of Canada, insurance companies and the stock exchange.

Most of the financial buildings on St. James Street were designed by anglophone architects. The same is true for institutional buildings such as the Old Court House and the Customs House designed by John Ostell, the Bonsecours Market and even the Notre-Dame Basillica (whose façade is the work of an Irish Protestant from New York, James O'Donnell). The only notable exception is the Montreal City Hall, which was inspired by the Hotel de Ville de Rennes. The character of the Victorian style of the late-19th-century buildings was a significant change from the stone masonry used during the French era and affected the appearance of Old Montreal.

Decline, preservation, and renewal

The district continued to grow during the early 20th century, evidenced by construction of prestigious buildings such as the Aldred Building (1929–1931), La Sauvegarde Building (1913), and the first Stock Exchange (1903–1904). Port activities, the financial sector, and the municipal government helped to maintain activity until the Great Depression began in 1929. During the Depression, the relocation of port facilities further east deprived Old Montreal of many companies related to the maritime trade, leaving many abandoned warehouses and commercial buildings. The downtown-area relocation several blocks to the north, and the near-complete absence of residents, (there were only a few hundred in 1950), had the effect of emptying the district when businesses closed at the end of the day. At that time, the lack of nightlife gave the district a reputation for being dangerous at night.

Old Montreal increasingly found itself changing to accommodate the rise of the automobile. Several prestigious locations, such as the Place d'Armes, the Place d'Youville, and Place Jacques-Cartier, were snarled with traffic in the mid-20th century. For municipal authorities, unaware of its potential heritage value, Old Montreal was an anomaly. City planners considered wider streets, which would have meant razing many older buildings. A proposed elevated highway along the river over the rue de la Commune spurred a movement to preserve the district. Dutch-born architect and urban planner Daniel van Ginkel played a major role in saving the district from destruction during the early 1960s. As assistant director of the City of Montreal's newly formed planning department, he persuaded authorities to abandon plans for an expressway that would have cut through the old city.[5] In 1964, most of Old Montreal was classified as a historic district; despite this, the Quebec government razed several 19th-century buildings to build a new courthouse.

In addition to the return of a residential base, the area has become attractive to the hotel industry. While in the 19th century all major hotels were in Old Montreal, by 1980 there were none. In 2009, there were about 20 hotels, mostly in restored older buildings. A steady stream of tourists and the presence of new residents encourage nightlife and entertainment. In addition, municipal authorities have invested large sums to renew the area's infrastructure. The Place Jacques-Cartier and part of the Place d'Youville have been redesigned, and a restoration of the Place d'Armes is in progress. A lighting plan was also developed to highlight the different façade styles. There is now a consensus that the historical legacy of Old Montreal is its major asset. Aided by redevelopment, it is now the leading tourist destination in Montreal.

Architecture and urban planning

Old Montreal is a major tourist attraction.[6] With some of its buildings dating to the 17th century, it is one of the oldest urban areas in North America. In the eastern part of the old city (near Place Jacques-Cartier) the following notable buildings can be found: Montreal City Hall, Bonsecours Market and Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours Chapel, as well as preserved colonial mansions, such as the Château Ramezay and the Sir George-Étienne Cartier National Historic Site of Canada. Further west, Place d'Armes is dominated by Notre-Dame Basilica] on its southern side, accompanied by the Saint-Sulpice Seminary (the oldest extant building in Montreal). The other sides of the square are devoted to commerce; to the north is the former Bank of Montreal Head Office and to the west, the Aldred Building and the 1888 New York Life Building, the oldest skyscraper in Canada. The rest of Saint Jacques Street is lined with old bank buildings (like the Old Royal Bank Building) from its heyday as Canada's financial centre.

.jpg)

The southwest of the old city contains important archeological remains of Montreal's first settlement (around Place d'Youville and Place Royale) in the Pointe-à-Callière museum. Architecture and cobbled streets in Old Montreal have been maintained or restored to keep the look of the city in its earliest days as a settlement, and horse-drawn calèches help maintain that image.

The old town's riverbank is taken up by the Old Port (Vieux-Port), whose maritime facilities are surrounded with recreational space and a variety of museums and attractions. The Iberville terminal on the Alexandra Pier serves as the cruise terminal for about 50,000 passengers annually from large cruise ships plying the St Lawrence Seaway.

Champ de Mars

Champ de Mars is a large public space located between Montreal City Hall and the Ville-Marie Expressway. It offers a view of downtown Montreal and Chinatown. It is notable due to its location and its archaeological remains. The two parallel lines of stone are one of the few spots in present-day Montreal where you can still see physical evidence of the fortified settlement from colonial times.

Transportation

Old Montreal is accessible from downtown via the Underground City and is served by several STM bus routes and the Champ-de-Mars, Place-d'Armes, and Square-Victoria-OACI Metro stations. Ferries to the south shore city of Longueuil are available during the summer, as are a network of bicycle paths.

References

- "Census Profile: Census Tract: 4620055.01". Canada 2011 Census. Statistics Canada. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- "Old Montréal / Centuries of History - Ville-Marie". www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal". patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- "Explore Montreal's history through its monuments, public art: Four must-sees among hundreds of pieces". nationalpost.com. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- Martin, Sandra (July 23, 2009). "Sandy van Ginkel rescued Old Montreal from freeway developers". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- "Quais du Vieux-Port de Montréal : Bilan positif pour l'été 2009". arvm.ca/. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

Sources

- Lauzon, Gilles; Forget, Madeleine (2004). Old Montreal: History through Heritage. Montréal: Les Publications du Qhébec. p. 293. ISBN 2-551-19654-X.

- McLean, Eric (2004). The Living Past of Montreal. Montréal: McGill University Press. p. 64.

- Pinard, Guy (1987–1995). Montréal, son histoire, son architecture. (6 vol) Montréal: Éditions La Presse, Méridien. p. 1800 pages. ISBN 2-89415-039-3.CS1 maint: location (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Old Montreal. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Montreal/Old Montreal. |