Vestal Virgin

In ancient Rome, the Vestals or Vestal Virgins (Latin: Vestālēs, singular Vestālis [wɛsˈtaːlɪs]) were priestesses of Vesta, goddess of the hearth. The College of the Vestals was regarded as fundamental to the continuance and security of Rome. These individuals cultivated the sacred fire that was not allowed to go out. Vestals were freed of the usual social obligations to marry and bear children and took a 30-year vow of chastity in order to devote themselves to the study and correct observance of state rituals that were forbidden to the colleges of male priests.[1]

History

| Priesthoods of ancient Rome |

|---|

Flamen (250–260 CE) |

| Major colleges |

|

Pontifices · Augures · Septemviri epulonum Quindecimviri sacris faciundis |

| Other colleges or sodalities |

| Fetiales · Fratres Arvales · SaliiTitii · Luperci · Sodales Augustales |

| Priests |

|

Pontifex Maximus · Rex Sacrorum Flamen Dialis · Flamen Martialis Flamen Quirinalis · Rex NemorensisCurio maximus |

| Priestesses |

| Virgo Vestalis MaximaFlaminica Dialis · Regina sacrorum |

| Related topics |

| Religion in ancient Rome · Imperial cultGlossary of ancient Roman religionGallo-Roman religion |

Livy, Plutarch, and Aulus Gellius attribute the creation of the Vestals as a state-supported priestesshood to king Numa Pompilius, who reigned circa 717–673 BC. According to Livy, Numa introduced the Vestals and assigned them salaries from the public treasury. Livy also says that the priestesshood of Vesta had its origins at Alba Longa.[2] The 2nd century antiquarian Aulus Gellius writes that the first Vestal taken from her parents was led away in hand by Numa. Plutarch attributes the founding of the Temple of Vesta to Numa, who appointed at first two priestesses; Servius Tullius increased the number to four.[3] Ambrose alludes to a seventh in late antiquity.[4] Numa also appointed the pontifex maximus to watch over the Vestals.

The first Vestals, according to Varro, were named Gegania,[5] Veneneia,[6] Canuleia,[7] and Tarpeia.[8] Tarpeia, daughter of Spurius Tarpeius, was portrayed as traitorous in legend.

The Vestals became a powerful and influential force in the Roman state. When Sulla included the young Julius Caesar in his proscriptions, the Vestals interceded on Caesar's behalf and gained him pardon.[9] Augustus included the Vestals in all major dedications and ceremonies. They were held in awe, and attributed certain magical powers. Pliny the Elder, for example, in Book 28 of his Natural History discussing the efficacy of magic, chooses not to refute, but rather tacitly accept as truth:[10]

At the present day, too, it is a general belief, that our Vestal virgins have the power, by uttering a certain prayer, to arrest the flight of runaway slaves, and to rivet them to the spot, provided they have not gone beyond the precincts of the City. If then these opinions be once received as truth, and if it be admitted that the gods do listen to certain prayers, or are influenced by set forms of words, we are bound to conclude in the affirmative upon the whole question.

The urban prefect Symmachus, who sought to maintain traditional Roman religion during the rise of Christianity, wrote:

The laws of our ancestors provided for the Vestal virgins and the ministers of the gods a moderate maintenance and just privileges. This gift was preserved inviolate till the time of the degenerate moneychangers, who diverted the maintenance of sacred chastity into a fund for the payment of base porters. A public famine ensued on this act, and a bad harvest disappointed the hopes of all the provinces ... it was sacrilege which rendered the year barren, for it was necessary that all should lose that which they had denied to religion.[11]

The College of the Vestals was disbanded and the sacred fire extinguished in 394, by order of the Christian emperor Theodosius. Zosimus records how the Christian noblewoman Serena, a niece of Theodosius, entered the temple and took from the statue of the goddess Rhea Silvia a necklace and placed it on her own neck.[12] An old woman appeared, the last of the Vestals, who proceeded to rebuke Serena and called down upon her all just punishment for her act of impiety.[13] According to Zosimus, Serena was then subject to dreadful dreams predicting her own untimely death. Augustine would be inspired to write The City of God in response to murmurings that the capture of Rome and the disintegration of its empire was due to the advent of the Christian era, and its intolerance of the old gods who had defended the city for over a thousand years.

Vestalis Maxima

The chief Vestal (Virgo Vestalis Maxima or Vestalium Maxima, "greatest of the Vestals") oversaw the efforts of the Vestals, and was present in the College of Pontiffs. The Vestalis Maxima Occia presided over the Vestals for 57 years, according to Tacitus. The last known chief vestal was Coelia Concordia, who stepped down in 394 with the disbanding of the College of the Vestals by the Roman emperor Theodosius I.

The Vestalium Maxima was the most important of Rome's high priestesses. Although the Flaminica Dialis and the regina sacrorum each held unique responsibility for certain religious rites, each came into her office as the spouse of another appointed priest, whereas the vestals all held office independently.

Number of Vestals

According to Plutarch, there were only two Vestal Virgins when Numa began the College of the Vestals. This number later increased to four, and then to six.[14] It has been suggested by some authorities that a seventh was added later, but this is doubtful.[15]

Terms of service

The Vestals were committed to the priestesshood before puberty (when 6–10 years old) and sworn to celibacy for a period of 30 years.[16] These 30 years were divided in turn into decade-long periods during which Vestals were respectively students, servants, and teachers.

After her 30-year term of service, each Vestal retired and was replaced by a new inductee. Once retired, a former Vestal was given a pension and allowed to marry.[17] The Pontifex Maximus, acting as the father of the bride, would typically arrange a marriage with a suitable Roman nobleman. A marriage to a former Vestal was highly honoured, and – more importantly in ancient Rome – thought to bring good luck, as well as a comfortable pension.

Selection

To obtain entry into the order, a girl had to be free of physical and mental defects, have two living parents and be a daughter of a free-born resident of Rome. From at least the mid-Republican era, the pontifex maximus chose Vestals between their sixth and tenth year, by lot from a group of twenty high-born candidates at a gathering of their families and other Roman citizens. Originally, the girl had to be of patrician birth, but membership was opened to plebeians as it became difficult to find patricians willing to commit their daughters to 30 years as a Vestal, and then ultimately even from the daughters of freedmen for the same reason.[18][19]

The choosing ceremony was known as a captio (capture). Once a girl was chosen to be a Vestal, the pontifex pointed to her and led her away from her parents with the words, "I take you, Amata, to be a Vestal priestess, who will carry out sacred rites which it is the law for a Vestal priestess to perform on behalf of the Roman people, on the same terms as her who was a Vestal 'on the best terms' " (thus, with all the entitlements of a Vestal). As soon as she entered the atrium of Vesta's temple, she was under the goddess' service and protection.[20]

To replace a Vestal who had died, candidates would be presented in the quarters of the chief Vestal for the selection of the most virtuous. Unlike normal inductees, these candidates did not have to be prepubescents, nor even virgins (they could be young widows or even divorcees, though that was frowned upon and thought unlucky), though they were rarely older than the deceased Vestal they were replacing. Tacitus recounts how Gaius Fonteius Agrippa and Domitius Pollio offered their daughters as Vestal candidates in 19 AD to fill such a vacant position. Equally matched, Pollio's daughter was chosen only because Agrippa had been recently divorced. The pontifex maximus (Tiberius) "consoled" the failed candidate with a dowry of 1 million sesterces.[21]

Duties

Their tasks included the maintenance of the fire sacred to Vesta, the goddess of the hearth and home, collecting water from a sacred spring, preparation of food used in rituals and caring for sacred objects in the temple's sanctuary.[22] By maintaining Vesta's sacred fire, from which anyone could receive fire for household use, they functioned as "surrogate housekeepers", in a religious sense, for all of Rome. Their sacred fire was treated, in Imperial times, as the emperor's household fire.

The Vestals were put in charge of keeping safe the wills and testaments of various people such as Caesar and Mark Antony. In addition, the Vestals also guarded some sacred objects, including the Palladium, and made a special kind of flour called mola salsa which was sprinkled on all public offerings to a god.

Privileges

The dignities accorded to the Vestals were significant.[23]

- In an era when religion was rich in pageantry, the presence of the College of Vestal Virgins was required for numerous public ceremonies and wherever they went, were transported in a carpentum, a covered two-wheeled carriage, preceded by a lictor, and had the right-of-way;

- At public games and performances they had a reserved place of honour;

- Vestals gave evidence without the customary oath, their word being trusted without question;

- Vestals were, on account of their incorruptible character, entrusted with important wills and state documents, like public treaties;

- Their person was sacrosanct: death was the penalty for injuring their person and they had escorts to protect them from assault;

- They could free condemned prisoners and slaves by touching them – if a person who was sentenced to death saw a Vestal on his way to the execution, he was automatically pardoned;

- Vestals participated in throwing the ritual straw figures called Argei into the Tiber on May 15.[24][25]

Punishments

Allowing the sacred fire of Vesta to die out was a serious dereliction of duty. It suggested that the goddess had withdrawn her protection from the city. Vestals guilty of this offence were punished by a scourging or beating, which was carried out "in the dark and through a curtain to preserve their modesty".[26]

The chastity of the Vestals was considered to have a direct bearing on the health of the Roman state. When they entered the collegium, they left behind the authority of their fathers and became daughters of the state. Any sexual relationship with a citizen was therefore considered to be incestum and an act of treason.[27] The punishment for violating the oath of celibacy was to be buried alive in the Campus Sceleratus ("Evil Field") in an underground chamber near the Colline Gate supplied with a few days of food and water. Ancient tradition required that an unchaste Vestal be buried alive within the city, that being the only way to kill her without spilling her blood, which was forbidden. However, this practice contradicted the Roman law that no person might be buried within the city. To solve this problem, the Romans buried the offending priestess with a nominal quantity of food and other provisions, not to prolong her punishment, but so that the Vestal would not technically be buried in the city, but instead descend into a "habitable room". The actual manner of the procession to Campus Sceleratus has been described like this:

When condemned by the college of pontifices, she was stripped of her vittae and other badges of office, was scourged, was attired like a corpse, placed in a close litter, and borne through the forum attended by her weeping kindred, with all the ceremonies of a real funeral, to a rising ground called the Campus Sceleratus just within the city walls, close to the Colline gate. There a small vault underground had been previously prepared, containing a couch, a lamp, and a table with a little food. The pontifex maximus, having lifted up his hands to heaven and uttered a secret prayer, opened the litter, led forth the culprit, and placing her on the steps of the ladder which gave access to the subterranean cell, delivered her over to the common executioner and his assistants, who conducted her down, drew up the ladder, and having filled the pit with earth until the surface was level with the surrounding ground, left her to perish deprived of all the tributes of respect usually paid to the spirits of the departed.[28]

Cases of unchastity and its punishment were rare.[29] In 483 BC, following a series of portents, and advice from the soothsayers that the religious ceremonies were not being duly attended to, the vestal virgin Oppia was found guilty of a breach of chastity and punished.[30] The Vestal Tuccia was accused of fornication, but she carried water in a sieve to prove her chastity.

O Vesta, if I have always brought pure hands to your secret services, make it so now that with this sieve I shall be able to draw water from the Tiber and bring it to Your temple.[31]

Because a Vestal's virginity was thought to be directly correlated to the sacred burning of the fire, if the fire were extinguished it might be assumed that either the Vestal had acted wrongly or that the vestal had simply neglected her duties. The final decision was the responsibility of the Pontifex Maximus, or the head of the pontifical college, as opposed to a judicial body. While the Order of the Vestals was in existence for over one thousand years there are only ten recorded convictions for unchastity and these trials all took place at times of political crisis for the Roman state. It has been suggested[27] that Vestals were used as scapegoats[32] in times of great crisis.

Pliny the Younger was convinced that Cornelia, who as Virgo Maxima was buried alive at the orders of emperor Domitian, was innocent of the charges of unchastity, and he describes how she sought to keep her dignity intact when she descended into the chamber:[33]

... when she was let down into the subterranean chamber, and her robe had caught in descending, she turned round and gathered it up. And when the executioner offered her his hand, she shrank from it, and turned away with disgust; spurning the foul contact from her person, chaste, pure, and holy: And with all the deportment of modest grace, she scrupulously endeavoured to perish with propriety and decorum.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus claims that the earliest Vestals at Alba Longa were whipped and "put to death" for breaking their vows of celibacy, and that their offspring were to be thrown into the river.[34] According to Livy, Rhea Silvia, the mother of Romulus and Remus, had been forced to become a Vestal Virgin, and when she gave birth to the twins, it is stated that she was merely loaded down with chains and cast into prison, her babies put into the river.[35] Dionysius also relates the belief that live burial was instituted by the Roman king Tarquinius Priscus, and inflicted this punishment on the priestess Pinaria.[36] The 11th century Byzantine historian George Kedrenos is the only extant source for the claim that prior to Priscus, the Roman King Numa Pompilius had instituted death by stoning for unchaste Vestal Virgins, and that it was Priscus who changed the punishment into that of live burial.[37] But whipping with rods sometimes preceded the immuration as was done to Urbinia in 471 BC.[38]

Suspicions first arose against Minucia through an improper love of dress and the evidence of a slave. She was found guilty of unchastity and buried alive.[39] Similarly Postumia, who though innocent according to Livy[40] was tried for unchastity with suspicions being aroused through her immodest attire and less than maidenly manner. Postumia was sternly warned "to leave her sports, taunts, and merry conceits". Aemilia, Licinia, and Martia were executed after being denounced by the servant of a barbarian horseman. A few Vestals were acquitted. Some cleared themselves through ordeals.[41] The paramour of a guilty Vestal was whipped to death in the Forum Boarium or on the Comitium.[42]

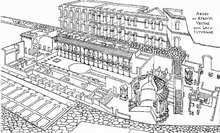

House of the Vestals

The House of the Vestals was the residence of the vestal priestesses in Rome. Behind the Temple of Vesta (which housed the sacred fire), the Atrium Vestiae was a three-storey building at the foot of the Palatine Hill.

Vestal festivals

The chief festivals of Vesta were the Vestalia celebrated June 7 until June 15. On June 7 only, her sanctuary (which normally no one except her priestesses the Vestals entered) was accessible to mothers of families who brought plates of food. The simple ceremonies were officiated by the Vestals and they gathered grain and fashioned salty cakes for the festival. This was the only time when they themselves made the mola salsa, for this was the holiest time for Vesta, and it had to be made perfectly and correctly, as it was used in all public sacrifices.

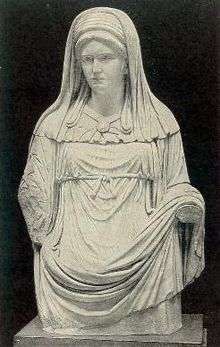

Attire

Romans used clothes to express important aspects of their culture, specifically gender and sexuality. The implications of the attire of the Vestal Virgins emphasize the Roman principle of sexual propriety.[43] Throughout time, the image of the Vestal Virgin has been a woman draped in white priestly garments denoting the essence of purity and divinity through such attire.[44]

The important elements of the Vestal costume include the stola and the vittae. It is important to note that these two items are closely related to the traditional attire of Roman brides and the Roman matron, and therefore are not unique to the Vestals. The vittae that the Vestals wore was a cloth ribbon worn in the Vestals' hair. It is closely associated with status of Roman matron. Vittae were worn by a wider range of women at different stages of life and therefore cannot be accepted as unique to just one stage. Unmarried girls, matrons, as well as the Vestal virgins all wore them.

However, the Vestals did not share all elements of the bride's attire, specifically they did not wear the flammeum that brides did, but instead wore the suffibulum. The vestals also wore a stola, which is associated with Roman matrons, not with Roman brides. Furthermore, the manner in which the Vestals styled their hair was the way that Roman brides wore their hair on their wedding day. This juxtaposition between the attire and style worn by Vestal Virgins and brides or matrons is particularly intriguing and studied by scholars in numerous instances.

The gowns worn by the Vestals and Roman brides were also similar in the way that they were tied. The distinction, though is that the Vestals wore the stola, which is associated more with matrons, while brides were associated with the tunica recta. The stola is a long gown that covers the body, and this covering of the body by way of the gown "signals the prohibitions that governed [the Vestals] sexuality".[45] Stola literally communicates the message of "hands off" and further communicates their virginity.[46]

The connection between Vestals and Roman brides suggest that the Vestals have the connotation of being ambivalent. They are perceived as eternally stuck at the moment between virginal status and marital status.

The main articles of their clothing consisted of an infula, a suffibulum, and a palla. The infula was a fillet, which was worn by priests and other religious figures in Rome. A vestal's infula was white and made from wool. The suffibulum was the white woolen veil which was worn during rituals and sacrifices. Usually found underneath were red and white woolen ribbons, symbolizing the Vestal's commitment to keeping the fire of Vesta and to her vow of purity, respectively. The palla was the long, simple shawl, a typical article of clothing for Roman women. The palla, and its pin, were draped over the left shoulder.

Vestals also had an elaborate hairstyle consisting of six or seven braids, which Roman brides also wore.[47][48][49][50] In 2013 Janet Stephens became the first to recreate the hairstyle of the vestals on a modern person.[50][51]

List of Vestals

From the institution of the Vestal priesthood to its abolition, an unknown number of Vestals held office. Several are named in Roman myth and history.

Legendary Vestals

- Rhea Silvia, a vestal at Alba Longa, was the mythical mother of Rome's founders, Romulus and Remus.

- Aemilia, a Roman vestal who prayed to Vesta for assistance on one occasion when the sacred fire was extinguished, and then miraculously rekindled it by throwing a piece of her garment upon the extinct embers.[52]

Vestals in the Republic (509–27 BC)

- Oppia was a Vestal Virgin in the early republic. In 483, following a series of portents, and advice from the soothsayers that the religious ceremonies were not being duly attended to, she was found guilty of a breach of chastity and punished.[30]

- Orbinia, put to death for misconduct in 471.[53]

- Postumia, tried for misconduct in 420, but acquitted.[54]

- Minucia, put to death for misconduct in 337.[55]

- Sextilia, put to death for misconduct in 273.[56]

- Caparronia, committed suicide in 266 when accused of misconduct.[57]

- Tuccia, accused of misconduct, perhaps in 230, she proved her innocence.[58][59]

- Floronia, Opimia, convicted of misconduct in 216, one was buried alive, the other committed suicide.[60]

- Claudia Ap. f. Ap. n., daughter of Appius Claudius Pulcher, consul in 143. During the triumph of her father, she walked beside him to repulse a tribune of the plebs, who was trying to veto his triumph.[61]

- Licinia C. f., vestal in 123, her dedication of an altar was cancelled by the pontiffs because it had been done without the approval of the people. She was possibly the same as the vestal executed for misconduct in 113.[62]

- Aemilia, Marcia, and Licinia, accused of multiple acts of incestum (violations of their vows of chastity) in 114.[63][64][65] Aemilia, who had supposedly led the two others to follow her example, was condemned outright and put to death.[66] Marcia, who was accused of only one offence, and Licinia, who was accused of many, were at first acquitted by the pontifices, but were retried by Lucius Cassius Longinus Ravilla (consul 127), and condemned to death in 113.[67][68] The prosecution offered two Sibylline prophecies in support of the final verdicts. The charges were almost certainly trumped up, and may have been politically motivated.[69][70]

- Fonteia, served c. 91–69, recorded as a Vestal during the trial of her brother in 69, but she would have begun her service before her father's death in 91.[71][72][73]

- Fabia, chief Vestal (b. c. 98–97; fl. 50), admitted to the order in 80, half-sister of Terentia (Cicero's first wife), and a wife of Dolabella who later married her niece Tullia; she was probably mother of the later consul of that name.[74] In 73 she was acquitted of incestum with Lucius Sergius Catilina.[75] The case was prosecuted by Cicero.

- Licinia (flourished 1st century) was supposedly courted by her kinsman, the so-called "triumvir" Marcus Licinius Crassus – who in fact wanted her property. This relationship gave rise to rumors. Plutarch says: "And yet when he was further on in years, he was accused of criminal intimacy with Licinia, one of the Vestal virgins and Licinia was formally prosecuted by a certain Plotius. Now Licinia was the owner of a pleasant villa in the suburbs which Crassus wished to get at a low price, and it was for this reason that he was forever hovering about the woman and paying his court to her, until he fell under the abominable suspicion. And in a way it was his avarice that absolved him from the charge of corrupting the Vestal, and he was acquitted by the judges. But he did not let Licinia go until he had acquired her property."[76] Licinia became a Vestal in 85 and remained a Vestal until 61.

- Arruntia, Perpennia M. f., Popillia, attended the inauguration of Lucius Cornelius Lentulus Niger as Flamen Martialis in 69. Licinia, Crassus' relative, was also present.[77]

- Occia, vestal for 57 years between 38 BC and 19 AD.[78]

Imperial Vestals

- Junia Torquata (1st-century), vestal under Tiberius, sister of Gaius Junius Silanus.[79]

- Rubria (1st-century), said by Suetonius to have been raped by Nero.

- Aquilia Severa (3rd century), whom Emperor Elagabalus married amid considerable scandal.

- Clodia Laeta (3rd century).

- Flavia Publicia (mid-3rd century).

- Coelia Concordia (4th century), the last head of the order.

Outside Rome

Inscriptions record the existence of Vestals in other locations than the centre of Rome.

- Manlia Severa, virgo Albana maxima,[80] a chief Alban Vestal at Bovillae whose brother was probably the L. Manlius Severus named as a rex sacrorum in a funerary inscription. Mommsen thought he was rex sacrorum of Rome, view that is now not considered probable.[81]

- Flavia (or Valeria) Vera, a virgo vestalis maxima arcis Albanae, chief Vestal Virgin of the Alban arx (citadel).[82]

- Caecilia Philete, a senior virgin (virgo maior) of Laurentum-Lavinium,[83] as commemorated by her father, Q. Caecilius Papion. The title maior means at Lavinium the Vestals were only two.

- Saufeia Alexandria, virgo Vestalis Tiburtium.[84]

- Cossinia L(ucii) f(iliae), a Virgo Vestalis of Tibur (Tivoli).[85]

- Primigenia, Alban vestal of Bovillae, mentioned by Symmachus in two of his letters.

Vestals in Western art

The Vestals were used as models of female virtue in allegorizing portraiture of the later West. Elizabeth I of England was portrayed holding a sieve to evoke Tuccia, the Vestal who proved her virtue by carrying water in a sieve.[86] Tuccia herself had been a subject for artists such as Jacopo del Sellaio (d. 1493) and Joannes Stradanus, and women who were arts patrons started having themselves painted as Vestals.[87] In the libertine environment of 18th century France, portraits of women as Vestals seem intended as fantasies of virtue infused with ironic eroticism.[88] Later vestals became an image of republican virtue, as in Jacques-Louis David's The Vestal Virgin. The discovery of a "House of the Vestals" in Pompeii made the Vestals a popular subject in the 18th century and the 19th century.

Portraits as Vestals

![]()

Sieve Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I (1583) by Quentin Metsys the Younger

Sieve Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I (1583) by Quentin Metsys the Younger Vestal Virgin (1677–1730) by Jean Raoux

Vestal Virgin (1677–1730) by Jean Raoux_by_Jean-Marc_Nattier.jpg) Madame Henriette de France as a Vestal Virgin (1749) by Jean-Marc Nattier

Madame Henriette de France as a Vestal Virgin (1749) by Jean-Marc Nattier Portrait of a Woman as a Vestal Virgin (1770s) by Angelica Kauffman

Portrait of a Woman as a Vestal Virgin (1770s) by Angelica Kauffman

References

- For an extensive modern consideration of the Vestals, see Ariadne Staples (1998). From Good Goddess to Vestal Virgins: Sex and Category in Roman Religion. Routledge.

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1:20.

- Life of Numa Pompilius 9.5–10 Archived 2012-12-03 at the Wayback Machine.

- Ambrose. "Letter #18". Letter to Emperor Valentianus. Newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 2012-10-22. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- English pronunciation: /dʒɪˈɡeɪniə/ ji-GAY-nee-ə

- /ˌvɛnɪˈniːə/ VEN-i-NEE-ə

- /ˌkænjʊˈliːə/ KAN-yuu-LEE-ə

- /tɑːrˈpiːə/ tar-PEE-ə

- Suetonius, Julius Caesar, 1.2.

- Pliny (1855), The Natural History of Pliny, Volume 5, p. 280.

- Ambrose of Milan. "The Memorial of Symmachus". The Letters of Ambrose. Tertullian.org. Archived from the original on 2012-08-12. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- Zosimus. "The New History". Tertullian.org. transcribed by Roger Pearse. p. 5:38. Archived from the original on 2013-01-31. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- Melissa Barden Dowling (January–February 2001). "The Curse of the Last Vestal". Archaeology Odyssey. Vol. 4 no. 1. Biblical Archaeology Society.

- Plutarch. Life of Numa. Translated by Langhorne.

- Cato; Worsfold, T. History of the Vestal Virgins of Rome. p. 22.

- Lutwyche, Jayne (2012-09-07). "Ancient Rome's maidens – who were the Vestal Virgins?". BBC. Archived from the original on 2012-10-01. Retrieved 2012-11-23.

- Plutarch. "Life of Numa Pompilius". Stoa.org. 9.5–10. Archived from the original on 2012-12-03. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- "Vestal Virgins". Ultimate Reference DVD. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2003.

- Kroppenberg, Inge (2010). "Law, Religion and Constitution of the Vestal Virgins". Law and Literature. 22 (3): 426–427. doi:10.1525/lal.2010.22.3.418.. The earlier, stricter selection rules were determined by the Papian Law of the 3rd century BC; they were waived as suitable high-born candidates became hard to find. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-10-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Aulus Gellius. "Vestal Virgins". Attic Nights. 1. STOA.org. p. 12. Archived from the original on 2012-12-03.

- Tacitus, Annales, ii.86

- "Vestal Virgins". Ultimate Reference Suite. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2003.

- Land, Graham (30 March 2015). "The Vestal Virgins: Rome's Most Independent Women". Made From History. Archived from the original on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Roman Antiquities. University of Chicago. i.19, 38.

- William Smith (1875). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London: John Murray – via University of Chicago.

- Culham, Phyllis (2014). Flower, Harriet I. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 143. ISBN 9781107669420.

- Melissa Barden Dowling (January–February 2001). "Vestal Virgins – Chaste Keepers of the Flame". Archaeology Odyssey. Vol. 4 no. 1. Biblical Archaeological Society.

- Smith, Anthon (1846). A school dictionary of Greek and Roman antiquities. London: Harper. p. 353.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1055.

- Livy. Ab urbe condita. 2.42.

- Valerius Maximus. Vestal Virgin Tuccia. 8.1.5 absol.

- Since the health of city was perceived in some way to be linked to the purity and spiritual health of the vestals, suspicions may have been fuelled in times of trouble. The allusions to a possible scapegoat could have been reinforced by the Vestals throwing Argei into the Tiber each year on May 15. cf. Martindale, C.C. "Religion of Ancient Rome". Studies in Comparative Religion. 2. CTS. 14:7.

- Noehden, G.H. (September 1817). "Essay, part 2". The Classical Journal. Some Observations on the Worship of Vesta. London: A.J.Valpy. XXXI: 321–333, 332.

online biography of G.H. Noehden

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus (1758). The Roman Antiquities of Dionysius Halicarnassensis. 1. Translated by Spelmann. p. 180.

- Livy (1844). History of Rome. 1. Translated by Baker. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 22.

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus (1758). The Roman antiquities of Dionysius Halicarnassensis. 2. Translated by Spelman. pp. 128–129.

- Smith, Anthon (1843), "A dictionary of Greek and Roman antiquities", New York: Harper & Brothers p.1040

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus (1758). The Roman antiquities of Dionysius Halicarnassensis. 4. p. 75.

- Livy. "History of Rome". Mcadams.posc.mu.edu. 8.15. Archived from the original on 2012-09-14. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- Livy. History of Rome. 4. Mcadams.posc.mu.edu. 4.44. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- "Patria Potestas". www.suppressedhistories.net. Archived from the original on 2005-12-03. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- Howatson, M. C. (1989). Oxford Companion to Classical Literature. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866121-4.

- Beard, Mary (1995). "Re-reading (Vestal) Virginity". In Richard Hawley; Barbara Levick (eds.). Women in Antiquity: New Assessments. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 166–177.

- Wagner, Kathryn. "The Power of Virginity: The Political Position and Symbolism of Ancient Rome's Vestal Virgin" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-17. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gallia, Andrew B. (2014-07-01). "The Vestal Habit". Classical Philology. 109 (3): 222–240. doi:10.1086/676291. ISSN 0009-837X.

- Beard, Mary (1980-01-01). "The Sexual Status of Vestal Virgins". The Journal of Roman Studies. 70: 12–27. doi:10.2307/299553. JSTOR 299553.

- Festus 454 in the edition of Lindsay, as cited by Robin Lorsch Wildfang, Rome's Vestal Virgins: A Study of Rome's Vestal Priestesses in the Late Republic and Early Empire (Routledge, 2006), p. 54

- Laetitia La Follette, "The Costume of the Roman Bride", in The World of Roman Costume (University of Wisconsin Press, 2001), pp. 59–60 (on discrepancies of hairstyles in some Vestal portraits)

- "Recreating the Vestal Virgin Hairstyle" video. Archived 2016-12-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Pesta, Abigail (7 February 2013). "On Pins and Needles: Stylist Turns Ancient Hairdo Debate on Its Head". Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018 – via www.wsj.com.

- "Ancient Rome's hairdo for vestal virgins re-created". nbcnews.com. 10 January 2013. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- Dionysus of Halicarnassus. Roman Antiquities. Thayer (Loeb ed.). University of Chicago. book II, 68, 3.;

Valerius Maximus, I.1.§7 - Dionysius of Halicarnassus, ix. 40.

- Livy, iv. 44.

- Livy, viii. 15.

- Livy, Periochae, 14.

- Orosius, iv. 5 § 9.

- Valerius Maximus, viii.1 § 5.

- Broughton, vol. I, pp. 227, 228 (note 2).

- Livy, xxii. 57.

- Cicero, Pro Caelio, 14.

- Cicero, Pro Domo Sua, 136.

- Beard, Mary; North, John; Price, Simon (9 July 1998). Religions of Rome: Volume 1, A History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521304016 – via Google Books.

- Greenidge, Abel Hendy Jones (17 December 2018). "A History of Rome". Methuen – via Google Books.

- Noorthouck, John (17 December 1776). An Historical and Classical Dictionary: Containing the Lives and Characters of the Most Eminent and Learned Persons, in Every Age and Nation, from the Earliest Period to the Present Time. In Two Volumes. W. Strahan; and T. Cadell – via Internet Archive.

Lucius Cassius vestal.

- Chrystal, Paul (17 May 2017). "Roman Women: The Women who influenced the History of Rome". Fonthill Media – via Google Books.

- Wildfang, Robin Lorsch, Rome's vestal virgins: a study of Rome's vestal priestesses in the late Republic and early Empire, Routledge/Taylor & Francis, 2007, p. 93ff

- Lightman, Marjorie; Lightman, Benjamin (17 December 2018). A to Z of Ancient Greek and Roman Women. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438107943 – via Google Books.

- Phyllis Cunham, in Harriet Flower (ed), The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic, Cambridge University Press, 2004, p.155 googlebooks partial preview. The accusations against Licinia included fraternal incest. She was a contemporary and possible political ally of the Gracchi brothers. In 123 BC the Roman Senate had annulled her attempted rededication of Bona Dea's Aventine Temple as illegal and "against the will of the people". She may have fallen victim to the factional politics of the times.

- Broughton, vol. I, p. 534.

- Cicero, Pro Fonteio 46–49

- Aulus Gellius 1.12.2

- T.R.S. Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic (American Philological Association, 1952), vol. 2, pp. 24–25.

- Wildfang, Robin Lorsch, Rome's vestal virgins: a study of Rome's vestal priestesses in the late Republic and early Empire, Routledge/Taylor & Francis, 2007, p. 96, preview via google books

- Lewis, R. G. (2001). "Catalina and the Vestal". The Classical Quarterly. JSTOR. 51 (1): 141–149. doi:10.1093/cq/51.1.141. JSTOR 3556336.

- Plutarch. "Life of Crassus". University of Chicago. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- Broughton, vol. II, pp. 135-137 (note 14).

- Broughton, vol. II, p. 395.

- Tacitus, Annales, iii. 69.

- CIL XIV, 2140 = ILS 6190, found in 1728 at the XI mile of the Via Appia, now in the Lapidary Gallery of the Vatican Museums: it mentions the dedication of a clipeus by her brother.

- CIL XIV, 2413 = ILS 4942 presently no longer reperible in the palazzo Mattei in Rome.

- CIL VI, 2172 = ILS 5011, found in Rome near the basilique of St. Saba, now in the Lapidary Gallery of the Vatican Museum. It is a dedicatory inscription on a little base, possibly of a statuette that was housed in the home of the same vestal on the Little Aventine. M. G. Granino Cecere "Vestali non di Roma" in Studi di epigrafia latina 20 2003 p. 70-71.

- Virgo maior regia Laurentium Lavinatium, CIL XIV, 2077, as read by Pirro Ligorio, now housed in the Palazzo Borghese at Pratica di Mare. Cecere above p. 72.

- CIL XIV, 3677 = ILS 6244 on the base of an honorary statue, now irreperible. Possibly also mentioned in CIL XIV, 3679. Cecere above p. 73-74

- Inscr. It. IV n. 213. Inscription on funerary monument discovered at Tivoli in July 1929. On the front the name of the Vestal is incised within an oak wreath onto which adheres the sacred infula, knot of the order; with the name of the dedicant (L. Cossinius Electus, a relative, probably brother or nephew) on the lower margin. Cecere above p. 75.

- Marina Warner, Monuments and Maidens: The Allegory of the Female Form (University of California Press, 1985), p. 244 ; Robert Tittler, "Portraiture, Politics and Society," in A Companion to Tudor Britain (Blackwell, 2007), p. 454; Linda Shenk, Learned Queen: The Image of Elizabeth I in Politics and Poetry (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), p. 13.

- Warner, Monuments and Maidens, p. 244.

- Kathleen Nicholson, "The Ideology of Feminine 'Virtue': The Vestal Virgin in French Eighteenth-Century Allegorical Portraiture," in Portraiture: Facing the Subject (Manchester University Press, 1997), p. 58ff.

Further reading

- Beard, Mary, "The Sexual Status of Vestal Virgins," The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 70, (1980), pp. 12–27.

- Broughton, T. Robert S., The Magistrates of the Roman Republic, American Philological Association (1952–1986).

- Kroppenberg, Inge, "Law, Religion and Constitution of the Vestal Virgins," Law and Literature, 22, 3, 2010, pp. 418 – 439.

- Peck, Harry Thurston, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898)

- Parker, Holt N. "Why Were the Vestals Virgins? Or the Chastity of Women and the Safety of the Roman State", American Journal of Philology, Vol. 125, No. 4. (2004), pp. 563–601.

- Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby, A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome

- Sawyer, Deborah F. "Magna Mater and the Vestal Virgins." In Women and Religion in the First Christian Centuries, 119-129. London: Routledge Press, 1996.

- Wildfang, Robin Lorsch. Rome's Vestal Virgins. Oxford: Routledge, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0-415-39795-2; paperback, ISBN 0-415-39796-0).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vestals. |

- Rodolfo Lanciani (1898) "The Fall of a Vestal" Chapter 6, in Ancient Rome in the Light of Recent Discoveries. Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston and New York, 1898.

- article Vestales in Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities

- House of the Vestal Virgins