Yuchi

The Yuchi people, spelled Euchee and Uchee, are people of a Native American tribe who historically lived in the eastern Tennessee River valley in Tennessee in the 16th century. The Yuchi built monumental earthworks. In the late 17th century, they moved south to Alabama, Georgia, and South Carolina.[2][3] Some also migrated to the panhandle of Florida. After suffering many fatalities from epidemic disease and warfare in the 18th century, several surviving Yuchi were removed to Indian Territory in the 1830s, together with their allies the Muscogee Creek.[2]

Yuchi people dancing the Big Turtle Dance, 1909 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2010: 623[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

Historically: Tennessee, then Alabama and Georgia Today: Oklahoma | |

| Languages | |

| English, Yuchi | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Methodist), Stomp Dance, Native American Church[2] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Muscogee Creek[2] |

Today, the Yuchi live primarily in the northeastern Oklahoma area, where many are enrolled as citizens in the federally recognized Muscogee (Creek) Nation.[2] Some Yuchi are enrolled as members of other federally recognized tribes, such as the Absentee Shawnee Tribe and the Cherokee Nation, also originally from the Southeast.

Name

The term Yuchi is commonly interpreted to mean "over there sit/live" or "situated yonder." Their autonym, or name for themselves, Tsoyaha or Coyaha, means "Children of the Sun." The Shawnee called them Tahokale, and the Cherokee call them Aniyutsi.[4]

History

At the time of first European contract, the Yuchi people lived in what is now central Tennessee.[3] In 1541, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto described them as a powerful tribe known as the as Uchi, that were also associated with the Chisca tribe.

Both historical and archaeological evidence exists documenting several Yuchi towns of the 18th century. Among these was Chestowee in present-day Bradley County, Tennessee. In 1714, instigated by two English fur traders from South Carolina, the Cherokee attacked and destroyed Chestowee. The Cherokee were prepared to carry their attacks further to Yuchi settlements on the Savannah River, but the colonial government of South Carolina did not condone the attacks. The Cherokee held back. The Cherokee destruction of Chestowee marked their emergence as a major power in the Southeast.[5]

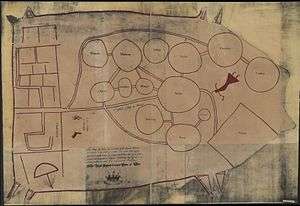

Yuchi towns were documented in Georgia and South Carolina, where the tribe had migrated to escape pressure from the Cherokee. "Mount Pleasant" was noted as being on the Savannah River in present-day Effingham County, Georgia, from about 1722 to about 1750. To take advantage of trade, the British established a trading post and small military garrison there, which they called Mount Pleasant.[6]

"Euchee Town" (also called Uche Town), a large settlement on the Chattahoochee River, was documented from the middle to late 18th century. It was located near Euchee (or Uche) Creek, about ten miles downriver from the Muscogee Creek settlement of Coweta Old Town. The naturalist William Bartram visited Euchee Town in 1778. In his letters he ranked it as the largest and most compact Indian town he had ever encountered, with large, well-built houses.[6][7] US Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins also visited the town and described the Yuchi as "more orderly and industrious" than the other tribes of the Creek Confederacy. The Yuchi began to move on, some into the Florida panhandle.

During the Creek War of 1813–1814, which overlapped the War of 1812, many Yuchi joined the Red Sticks party, traditionalists opposed to the Muscogee people of the Lower Towns, who had adopted more European ways. Euchee Town decayed. The tribe became one of the poorest of the Creek communities, at the same time gaining a bad reputation.[7] The archaeological site of the town, designated a National Historic Landmark, is within the boundaries of present-day Fort Benning, Georgia.

Colonists noted Patsiliga, a settlement on the Flint River, in the late 18th century. Other Yuchi settlements may have been those villages noted on the Oconee River near Uchee Creek in Wilkinson County, Georgia, and on Brier Creek in Burke County, Georgia or Screven County, Georgia. A Yuchi town was sited at present-day Silver Bluff in Aiken County, South Carolina from 1746 to 1751.[6]

During the 18th century, the Yuchi consistently allied with the British, with whom they traded deer hides and Indian slaves. Yuchi population plummeted in the 18th century due to Eurasian infectious diseases, to which they had no immunity, and to war with the Cherokee, who were moving into their territory. After the American Revolution, Yuchi people maintained close relations with the Muscogee Creek Confederacy. Some Yuchi migrated south to Florida along with the Creek, where they became part of the newly formed Seminole people.[8]

In the 1830s, the US government forcibly removed the Yuchi, along with the Muscogee Creek, from Alabama and Georgia to Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma), west of the Mississippi River. The Yuchi settled in the north and northwestern parts of the Creek Nation. Three towns which the Yuchi established in the 19th century continue today: Duck Creek, Polecat, and Sand Creek.[2][8]

Second Seminole War

Some Yuchi moved to near Lake Miccosukee in northern Florida prior to 1818. Andrew Jackson's invasion of the area during the First Seminole War caused the Yuchi to move to eastern Florida. They fought alongside the Seminoles during the Second Seminole War under their chief Uchee Billy. He was captured in 1837 with his brother Jack by General Joseph Marion Hernandez, who also captured Osceola.[9] They were imprisoned for years in Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida.[10]

Current status

While Yuchi people are enrolled in federally recognized tribes, they have also been trying to gain federal recognition as an independent tribe for more than 20 years. While the Yuchi have not been federally recognized, they have made some progress. They seek federal recognition as an individual tribe to ensure they could exercise self governance, have the ability to set up gaming casinos and other engines for economic development, as well as protect tribal customs and the unique Yuchi language.[11] As most descendants are enrolled in other federally recognized tribes already, they have not been successful. The unrecognized Euchee Tribe of Indians is headquartered in Sapulpa, Oklahoma. Their tribal chairmen are co-chairs Felix Brown Jr. and Clinton Sago.[12]

The tribe in Oklahoma were visited by Jim Anaya, United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Tracie Revis (Yuchi) gave a speech defining the importance of federal recognition. He acknowledged the declaration by the UN on the Rights of Indigenous People that states "that we have the right of self-determination and by virtue of that right- we may freely determine our political status and freely pursue our economic, social and cultural development."[13]

From 1890 to 1895, the Dawes Commission considered the Yuchi to be an autonomous tribe. It registered tribal members preparatory to allotment of communal tribal lands to individual households of members. Some 1200 tribal members were registered in those years. The Dawes Commission later decided to legally classify the Yuchi as part of the Muscogee Creek Nation, in an effort to simplify the process of land allotment. But this decision interrupted the autonomy of the people and their historical continuity as a recognized tribe.[14]

As of 1997, the Yuchi tribe had a formal enrollment of 249 members. Other persons who are Yuchi descendants are already enrolled in other tribes, such as the Creek. Most Yuchi are of multi-tribal descent and many are citizens of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, with whom it has had a close relationship. Some are citizens of other tribes, such as the Shawnee.

According to current estimates, there may be about 2,000 persons qualified to be members of a revived Yuchi tribe. They are descendants of some 1,100 persons recorded by the Indian Claims Commission in 1950.[15]

The Yuchi continue their important ceremonies such as the Green Corn Ceremony of summer. They also maintain three ceremonial grounds in Oklahoma. Some members belong to the Native American Church and Methodist congregations.[2]

In 2008, the Yuchi tribe received a grant from the Administration for Native Americans Comprehensive Community Survey and Plan. It was used to create the Tribal History Project, which began in October 2010.[15]

The Human Genome Project acknowledged the importance of the Yuchi distinct culture and language and approached the Yuchi in order to collect genetic data (DNA); however, the Yuchi tribe declined to participate in the Human Genome Project due to cultural conflict and uncertainty over government ownership of tribal DNA.[16]

Yuchi language

The Yuchi language is a linguistic isolate, not known to be related to any other language.[2] In 2000 the estimated number of fluent Yuchi speakers was 15, but this number dwindled to 7 by 2006.[17] According to a 2011 documentary on the Yuchi language, the number of first-language speakers has declined to five.[18]

Young Yuchi people have learned the language in recent years and are continuing to do so.[19] Yuchi language classes are being taught in Sapulpa, Oklahoma, in an effort led by Richard Grounds and the Euchee Language Project.[17] As of 2011, the Administration for Native Americans awarded the Yuchi tribe a grant for the years 2011 to 2014 in an effort to provide after-school programs for the youth to improve proficiency in their native language and develop a young generation of speakers.[20]

The Yuchi people and language are featured in a chapter in Mark Abley's Spoken Here: Travels Among Threatened Languages, a book on endangered languages.

Notable Yuchi people

- Uchee Billy (died 1837), warrior

- Chief Joseph Brown (1833-1935)

- Sam Story, 19th-century chief

- Richard Ray Whitman (born 1949), artist, poet, actor

References

Citations

- "2010 Census CPH-T-6. American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2010". Retrieved August 2, 2015.

- Jackson, Jason Baird. "Yuchi (Euchee)." Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Jackson 416

- Jackson 427–28

- Gallay, Alan (2002). The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670-1717. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10193-7.

- Daniel T. Elliott and Rita Folse Elliott, "Mount Pleasant. An Eighteenth-Century Yuchi Indian Town, British Trader Outpost, and Military Garrison in Georgia", Watkinsville, GA: LAMAR Institute Publications, 1990

- John T. Ellisor, The Second Creek War, p. 31

- Jackson 415

- Mahon, John K. (1985) [1967]. History of the Second Seminole War, 1835-1842 (Revised ed.). Gainesville: University Presses of Florida. pp. 6, 212. ISBN 0813001544. OCLC 12315671.

- Army and Navy Chronicle, Volumes 4-5, edited by Benjamin Homans, pp. 203-4

- "Oklahoma's Tribal Nations." Archived 2010-03-28 at the Wayback Machine Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. 2010 (retrieved 10 April 2010)

- "REPORT FROM THE EUCHEE (YUCHI) TRIBE OF INDIANS".

- "Euchee Tribe".

- "Euchee Tribe of Indians" (PDF).

- Grounds, Richard A. (Summer 1996). "The Yuchi Community and the Human Genome Diversity Project: Historic and Contemporary Ironies". Cultural Survival Quarterly.

- Anderton, Alice, PhD. "Status of Indian Languages in Oklahoma", Intertribal Wordpath Society, Ahalenia.com, 2006-2009 (retrieved 7 Feb 2009)

- Harjo, Sterlin and Matt Leach "We Are Still Here", This Land Press, 8 July 2011 (retrieved 8 July 2011)

- Associated Press, "Scientists Race Around World to Save Dying Languages", via Fox News, 2007-09-18. Accessed 2007-09-19.

- "Current ANA Grants Awarded Prior to FY 2012". January 3, 2013.

Bibliography

- Jackson, Jason Baird. "Yuchi." Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast. Eds. William C. Sturtevant and Raymond D. Fogelson. Volume 14. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2004. ISBN 0-16-072300-0.

Further reading

- Mark Abley, Spoken Here: Travels Among Threatened Languages, Houghton Mifflin, 2003.

- Jason Jackson, Yuchi Ceremonial Life: Performance, Meaning, and Tradition in a Contemporary American Indian Community, University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

- Jason Baird Jackson (ed.), Yuchi Indian Histories Before the Removal Era. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2012.

- Frank Speck, Ethnology of the Yuchi Indians (reprint), University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

- Daniel Elliott, Ye Pleasant Mount: 1989&1990 Excavations. The LAMAR Institute, University of Georgia, 1991.

External links

- The Euchee Language Project

- Memoirs of Jeremiah Curtin in the Indian Territory, pp. 327, 333-335. 19th century ethnographer's account of learning Yuchi language in 1883 in a Yuchi settlement 55 miles from Muskogee, Oklahoma. Electronic record maintained by Library of Congress, accessed January 15, 2007.

- Uchee Path historical marker

- Joseph Mahan Collection, Columbus State University Archives