Oconee River

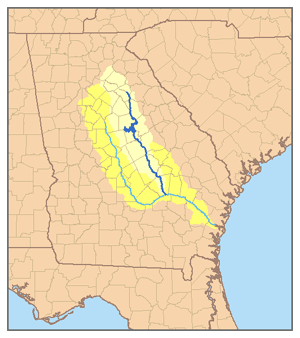

The Oconee River is a 220-mile-long (350 km)[1] river in the U.S. state of Georgia. Its origin is in Hall County and it terminates where it joins the Ocmulgee River to form the Altamaha River near Lumber City at the borders of Montgomery County, Wheeler County, and Jeff Davis County. South of Athens, two forks, known as the Middle Oconee River and North Oconee River, which flow for 55–65 miles (89–105 km) upstream respectively before converging to form the Oconee River.[2] Milledgeville, the former capital city of Georgia, lies on the Oconee River.

The Oconee River Greenway trail along the Oconee River in Milledgeville opened in 2008[3] and the North Oconee River Greenway section of the trail is in Athens, Georgia. J.W. McMillan's brick factory was located along the river.

Course

The Oconee River passes through the Oconee National Forest into Lake Oconee, a man made lake, near the towns of Madison and Greensboro off Interstate 20. From Lake Oconee, the river travels to Lake Sinclair, another manmade lake in Milledgeville, the town founded on Georgia's Fall Line and former state capital. South of Milledgeville, the river flows unobstructed and later merges with the Ocmulgee River to form the Altamaha River. Along the river there are many sandbars and oxbow lakes while the forest bottomland swamp surrounding the Oconee extends for miles, creating a very remote setting.

Name origin

The river's name derives from the Oconee, a Muskogean people of central Georgia. The Oconee lived in present-day Baldwin County, Georgia at a settlement known as Oconee Old Town, later moving to the Chattahoochee River in the early 18th century. The name exists in several variations, including Ocone, Oconi, Ocony, and Ekwoni.[4]

River pollution

Fecal coliform bacteria

One of the main sources of pollution comes from fecal coliform bacteria, several species of bacteria found in human and animal feces. Fecal coliform bacteria enter the river through a number of sources; stormwater runoff leaving farmlands, stormwater runoff carrying pet waste, leaking septic and sewer lines contaminating surface or groundwater, and sewer spills throughout the watershed. Fecal coliform bacteria can be deadly to humans if ingested or acquired through an open wound. Fish caught in the Oconee Basin may be eaten if cooked thoroughly.[5]

Fertilizer runoff

The second biggest form of pollution in the river is fertilizer. Nitrogen in fertilizer in the form of nitrates or ammonia, measured in parts per million, is found in regularly collected samples. These forms of nitrogen stimulate abundant growth of algae in the water. The effect is twofold:

- The water becomes murkier from the algae growing in it. This inhibits sunlight's path to the bottom of the river and destroys naturally occurring plant life at the bottom of the ecosystem.

- The algae eventually die and rot in the water; as they decompose, they pull oxygen out of the water, killing fish, especially large ones. This affects other wildlife, including birds, dependent on the fish and the river for survival.

Sedimentation

The third largest source of pollution (?) is sedimentation, typically caused by construction and urbanization. Loose soil washes away with rainwater, clouding the river and eventually settling to the bottom at a faster rate than the river can naturally carry it away. This reduces clarity in the same way as the algal growth. In addition, the buildup of the bottom reduces the depth of the water, affecting flow and raising the temperature of the river, stressing the ecosystem.

References

- U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map, accessed April 21, 2011

- "Ocenee River". Georgia River Network. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Oconee River Greenway

- Krakow, Kenneth K. (1999). Georgia Place-names (PDF). Macon, GA.: Winship Press. pp. 163–164. ISBN 0-915430-00-2.

- Georgia Environmental Protective Division; Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Fish Consumption Guidelines http://gaepd.org/Documents/fish_guide.html