Turoyo language

Turoyo, also referred to as Surayt, is a Central Neo-Aramaic language traditionally spoken in southeastern Turkey and northern Syria by Arameans. Most speakers use the Classical Syriac language for literature and worship.

| Turoyo | |

|---|---|

| Sūrayṯ | |

| ܣܘܪܝܬ | |

| Pronunciation | [su:rajtʰ] |

| Native to | Turkey, Syria |

| Region | Mardin Province of southeastern Turkey; Al-Hasakah Governorate in northeastern Syria |

Native speakers | 103,300 (2019)[1] |

| Syriac (Serto) Latin (Turoyo alphabet) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | tru |

| Glottolog | turo1239[2] |

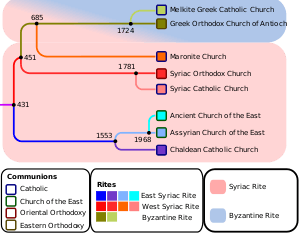

Turoyo speakers are currently mostly members of the Syriac Orthodox Church, but there are also Turoyo-speaking members of the Chaldean Catholic Church, especially from the town of Midyat, and of the Assyrian Church of the East. It is also currently spoken in the Aramean diaspora, although classified as a vulnerable language.[3][4]

Turoyo is not mutually intelligible with Western Neo-Aramaic having been separated for over a thousand years, while mutual intelligibility with Assyrian Neo-Aramaic and Chaldean Neo-Aramaic is limited.[5]

Contrary to what these language names suggest, they are not specific to a particular church, with members of the Assyrian Church of the East and Chaldean Catholic Church speaking Assyrian dialects, and members of the Syriac Orthodox Church speaking Turoyo.

Etymology

From the word ṭuro, meaning 'mountain', Ṭuroyo is the mountain tongue of the Tur Abdin in southeastern Turkey. Another name for the language is Surayt,[6] and it is used by a number of speakers of the language, as well as the recent EU funded programme to revitalize the language in preference to Ṭuroyo, since Surayt is a historical name for the language used by Syriacs while Turoyo is an academic name for the language used to distinguish it from other Neo-Aramaic languages and Classical Syriac. However, especially in the diaspora, the language is frequently called Surayt, Suryoyo, or Suroyo (or Sureyt, Sŭryoyo or Süryoyo depending on dialect), meaning "Syriac". Turoyo is sometimes also referred to as Western Syriac.

History

Turoyo has evolved from the Eastern Aramaic colloquial varieties that have been spoken in Tur Abdin and the surrounding plain for more than a thousand years since the initial introduction of Aramaic to the region. However, it has also been influenced by Classical Syriac, which itself was the variety of the Eastern Middle Aramaic spoken farther west, in the city of Edessa. Due to the proximity of Tur Abdin to Edessa, and the closeness of their parent languages, meant that Turoyo bears a greater similarity to Classical Syriac than do Northeastern Neo-Aramaic varieties.

The homeland of Turoyo is the Tur Abdin region in southeastern Turkey.[7] This region is a traditional stronghold of Syriac Orthodox Christians.[8] The Turoyo-speaking population prior to the Syriac genocide largely adhered to the Syriac Orthodox Church.[7] In 1970 it was estimated that there were 20,000 Turoyo-speakers still living in the area, however, they gradually migrated to Western Europe and elsewhere in the world.[7] The Turoyo-speaking diaspora is now estimated at 40,000.[7] In the diaspora communities, Turoyo is usually a second language which is supplemented by more mainstream languages.[9] The language is considered endangered by UNESCO, but efforts are still made by Turoyo-speaking communities to sustain the language through use in homelife, school programs to teach Turoyo on the weekends, and summer day camps.[10][11] Today only hundreds of speakers remain in Tur Abdin.[7]

Until recently, Turoyo was a spoken vernacular and was never written down: Kthobhonoyo was the written language. In the 1880s, various attempts were made, with the encouragement of western missionaries, to write Turoyo in the Syriac alphabet, in the Serto and in "Estrangelo" script used for West-Syriac Kthobhonoyo.

However, with upheaval in their homeland through the twentieth century, many Turoyo speakers have emigrated around the world (particularly to Syria, Lebanon, Sweden and Germany). The Swedish government's education policy, that every child be educated in his or her first tongue, led to the commissioning of teaching materials in Turoyo. Yusuf Ishaq thus developed an alphabet for Turoyo based on the Latin script. Silas Üzel also created a separate Latin alphabet for Turoyo in Germany.

A series of reading books and workbooks that introduce Ishaq's alphabet are called Toxu Qorena!, or "Come Let's Read!" This project has also produced a Swedish-Turoyo dictionary of 4500 entries: the Svensk-turabdinskt Lexikon: Leksiqon Swedoyo-Suryoyo. Another old teacher, writer and translator of Turoyo is Yuhanun Üzel (born in Midun in 1934) who in 2009 finished the translation of the Peshitta Bible in Turoyo, with Benjamin Bar Shabo and Yahkup Bilgic, in Serto (West-Syriac) and Latin script, a foundation for the "Aramean-Syriac language".

Dialects

Turoyo has borrowed some words from Arabic, Kurdish, Armenian, and Turkish. The main dialect of Turoyo is that of Midyat (Mëḏyoyo), in the east of Turkey's Mardin Province. Every village have distinctive dialects (Midwoyo, Kfarzoyo, `Iwarnoyo, Nihloyo and Izloyo, respectively). All Turoyo dialects are mutually intelligible with each other. There is a dialectal split between the town of Midyat and the villages, with only slight differences between the individual villages.[7] A closely related language or dialect, Mlaḥsô, spoken in two villages in Diyarbakir, is now deemed extinct.[7]

Many Turoyo-speakers who have left their villages now speak a mixed dialect of their village dialect with the Midyat dialect. This mixture of dialects was used by Ishaq as the basis of his system of written Turoyo. For example, Ishaq's reading book uses the word qorena in its title instead of the Mëḏyoyo qurena or the village-dialect qorina. All speakers are bilingual in another local language. Church schools in Syria and Lebanon teach Kthobonoyo rather than Turoyo, and encourage the replacement of non-Syriac loanwords with authentic Syriac ones. Some church leaders have tried to discourage the use and writing of Turoyo, seeing it as an impure form of Syriac.

Alphabet

Turoyo is written both in Latin and Syriac (Serto) characters. The orthography below was the outcome of the International Surayt Conference held at the University of Cambridge (27-30 August 2015).[12][13]

| Latin letter | ' | B b | V v | G g | Ġ ġ | J j | D d | Ḏ ḏ | H h | W w | Z z | Ž ž | Ḥ ḥ | Ṭ ṭ | Ḍ ḍ | Y y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syriac letter | ܐ | ܒ | ܒ݂ | ܓ | ܓ݂ | ܔ | ܕ | ܕ݂ | ܗ | ܘ | ܙ | ܙ̰ | ܚ | ܛ | ܜ | ܝ |

| Pronunciation | [ʔ], ∅ | [b] | [v] | [g] | [ɣ] | [dʒ] | [d] | [ð] | [h] | [w] | [z] | [ʒ] | [ħ] | [tˤ] | [dˤ] | [j] |

| Latin letter | K k | X x | L l | M m | N n | S s | C c | P p | F f | Ṣ ṣ | Q q | R r | Š š | Č č | T t | Ṯ ṯ |

| Syriac letter | ܟ | ܟ݂ | ܠ | ܡ | ܢ | ܣ | ܥ | ܦ݁ | ܦ | ܨ | ܩ | ܪ | ܫ | ܫ̰ | ܬ | ܬ݂ |

| Pronunciation | [k] | [x] | [l] | [m] | [n] | [s] | [ʕ] | [p] | [f] | [sˤ] | [q] | [r] | [ʃ] | [tʃ] | [t] | [θ] |

| Latin letter | A a | Ä ä | E e | Ë ë | O o | Y/I y/i | W/U w/u |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syriac vowel mark (or mater lectionis) |

ܰ | ܱ | ܶ | ܷ | ܳ | ܝ | ܘ |

| Pronunciation | [a] | [ă] | [e] | [ə] | [o] | [j]/[i] | [w]/[u] |

Attempts to write down Turoyo have begun since the 16th century, with Jewish Neo-Aramaic adaptions and translations of Biblical texts, commentaries, as well as hagiographic stories, books, and folktales in Christian dialects.[14] The Nestorian Bishop Mar Yohannan working with American missionary Rev. Justin Perkins also tried to write the vernacular version of religious texts, culminating in the production of school-cards in 1836.[14]

In 1970s Germany, members of the Syriac evangelical movement (Aramäische freie Christengemeinde in German) used Turoyo to write short texts and songs.[15] The Syriac evangelical movement has also published over 300 Turoyo hymns in a compedium named Kole Ruhonoye in 2012, as well as translating the four gospels with Mark and John being published so far.[15]

The alphabet as used in a forthcoming translation of New Peshitta in Turoyo by Yuhanun Bar Shabo, Sfar mele surtoṯoyo - Picture dictionary and Benjamin Bar Shabo's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

In the 1970s, educator Yusuf Ishaq attempted to systematically incorporate the Turoyo language into a Latin orthography, which resulted in a series of reading books, entitled [toxu qorena].[10] Although this system is not used outside of Sweden, other Turoyo speakers have developed their own non-standardized Latin script to use the language on digital platforms.

The Swedish government's "mother-tongue education" project treated Turoyo as an immigrant language, like Arabic, Turkish, Kurdish, and began to teach the language in schools.[15] The staff of the National Swedish Institute for Teaching Material produced a Latin letter-based alphabet, grammar, dictionary, school books, and instructional material. Due to religious and political objections, the project was halted.[15]

There are other efforts to translate famous works of literature, including The Aramaic Students Association's translation of The Little Prince, the Nisbin Foundation's translation of Cinderella and Little Red Riding Hood.[15]

Phonology

Phonetically, Turoyo is very similar to Classical Syriac. The additional phonemes /d͡ʒ/ (as in judge), /t͡ʃ/ (as in church) /ʒ/ (as in azure) and a few instances of /ðˤ/ (the Arabic ẓāʾ) mostly only appear in loanwords from other languages.

The most distinctive feature of Turoyo phonology is its use of reduced vowels in closed syllables. The phonetic value of such reduced vowels differs depending both on the value of original vowel and the dialect spoken. The Miḏyoyo dialect also reduces vowels in pre-stress open syllables. That has the effect of producing a syllabic schwa in most dialects (in Classical Syriac, the schwa is not syllabic).

Morphology

The verbal system of Turoyo is similar to that used in other Neo-Aramaic languages. In Classical Syriac, the ancient perfect and imperfect tenses had started to become preterite and future tenses respectively, and other tenses were formed by using the participles with pronominal clitics or shortened forms of the verb hwā ('to become'). Most modern Aramaic languages have completely abandoned the old tenses and form all tenses from stems based around the old participles. The classical clitics have become incorporated fully into the verb form, and can be considered more like inflections.

Turoyo has also developed the use of the demonstrative pronouns much more than any other Aramaic language. In Turoyo, they have become definite articles:

- masculine singular: u malko (the king)

- feminine singular: i malëkṯo (the queen)

- plural common: am malke (the kings), am malkoṯe (the queens).

The Modern Western Syriac dialect of Mlahsô and Ansha villages in Diyarbakır Province is quite different from Turoyo. It is virtually extinct; its last few speakers live in Qamishli in northeastern Syria and in the diaspora. Turoyo is also more closely related to other Eastern Neo-Aramaic dialects than the Western Neo-Aramaic dialect of Maaloula.[17]

Syntax

Turoyo has three sets of particles that take the place of the copula in nominal clauses: enclitic copula, independent copula, and emphatic independent copula. In Turoyo, the non-enclitic copula (or the existential particle) is articulated with the use of two sets of particles: kal and kit.[14]

References

- https://www.ethnologue.com/language/tru

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Turoyo". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- "Did you know Turoyo is vulnerable?". Endangered Languages. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- Saouk, J (2015). "Quo Vadis Turoyo? A Description of the Needs of the Neo-Aramaic of Tur-Abdin (Turkey)". Parole de L'Orient.

- Brenzinger, Matthias (2007). Language Diversity Endangered. Walter de Gruyter. p. 268. ISBN 9783110170498.

- Aramaic (Assyrian/Syriac) Dictionary and Phrasebook - Nicholas Awde, Nineb Lamassu, Nicholas Al-Jeloo - Google Boeken. Books.google.com. 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- Weninger 2012, p. 697.

- Aphram I. Barsoum; Ighnāṭyūs Afrām I (Patriarch of Antioch) (2008). The History of Tur Abdin. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-715-5.

- Weaver, C; Kiraz, G (2016). "Turoyo Neo-Aramaic in northern New Jersey". International Journal of the Sociology of Language.

- Weaver, C.M.; Kiraz, G.A. (2016). "Turoyo Neo-Aramaic in northern New Jersey". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. doi:10.1515/ijsl-2015-0033.

- "Turoyo « Sorosoro". www.sorosoro.org. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- https://aramaic.geschkult.fu-berlin.de/course/en/a1-intro#1

- http://userblogs.fu-berlin.de/wp-includes/ms-files.php?path=/aramaic-ol/&file=2017/08/Surayt-Orthography.pdf

- Tomal, Maciej (2015). Khan, Geoffrey; Napiorkowska, Lidia, eds. Towards a Description of Written Surayt/Turoyo: Some Syntactic Functions of the Particle Kal. Gorgias Press.

- Talay, Shabo (2015). "Turoyo, the Aramaic Language of Turabdin and the Translation of Alice". In Lindseth, Jon A. Alice In a World of Wonderland The Translations of Lewis Carroll's Masterpiece. Oak Knoll Press.

- Jastrow, Otto (2011). Ṭuroyo and Mlaḥsô. The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook: De Gruyter & Mouton. pp. 697–707.

- Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 31, No. 3 (1968), pp. 605-610

Sources

- Shlomo Izreʾel; Shlomo Raz (1996). Studies in Modern Semitic Languages. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10646-4.

- Wolfhart Heinrichs (1990). Studies in Neo-Aramaic. Scholars Press. ISBN 978-1-55540-430-7.

- Weninger, Stefan (2012). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Beth-Sawoce, Jan (2012). Xëzne d xabre/Ordlista Surayt-Swedi [mëdyoyo]. Södertälje: Nsibin. ISBN 978-91-88328-57-1

- Jastrow, Otto (1985). Laut- und Formenlehre des neuaramäischen Dialekts von Mīdin im Ṭur cAbdīn. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag: Wiesbaden.

- Jastrow, Otto (1992). Lehrbuch der Ṭuroyo-Sprache. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag: Wiesbaden. ISBN 3-447-03213-8.

- Tezel, Aziz (2003). Comparative Etymological Studies in the Western Neo-Syriac (Ṭūrōyo) Lexicon: with special reference to homonyms, related words and borrowings with cultural signification. Uppsala Universitet. ISBN 91-554-5555-7.

- Waltisberg, Michael (2016). Syntax des Ṭuroyo (= Semitica Viva 55). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag: Wiesbaden. ISBN 978-3-447-10731-0.

External links

- Turoyo alphabets and pronunciation at Omniglot

| Turoyo language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |