Ẓāʾ

Ẓāʾ, or ḏ̣āʾ (ظ), is one of the six letters the Arabic alphabet added to the twenty-two inherited from the Phoenician alphabet (the others being ṯāʾ, ḫāʾ, ḏāl, ḍād, ġayn). In Classical Arabic, it represents a velarized voiced dental fricative [ðˠ], and in Modern Standard Arabic, it can also be a pharyngealized, [ðˤ] voiced dental fricative or voiced alveolar fricative [zˤ]. In name and shape, it is a variant of ṭāʾ. Its numerical value is 900 (see Abjad numerals).

| Arabic alphabet |

|---|

|

Arabic script |

|

| Ẓāʾ | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| Phonemic representation | ðˤ~zˤ, dˤ | |||||||||

| Position in alphabet | 27 | |||||||||

| Numerical value | 900 | |||||||||

| Alphabetic derivatives of the Phoenician | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Ẓāʾ | |

|---|---|

| ظ | |

| Usage | |

| Writing system | Arabic script |

| Type | Abjad |

| Language of origin | Arabic language |

| Phonetic usage | ðˤ~zˤ, dˤ |

| History | |

| Development |

|

| Other | |

Ẓāʾ does not change its shape depending on its position in the word:

| Position in word: | Isolated | Final | Medial | Initial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyph form: (Help) |

ظ | ـظ | ـظـ | ظـ |

Pronunciation

In Classical Arabic, it represents a velarized voiced dental fricative [ðˠ], and in Modern Standard Arabic, it can also be a pharyngealized, [ðˤ] voiced dental fricative or voiced alveolar fricative [zˤ].

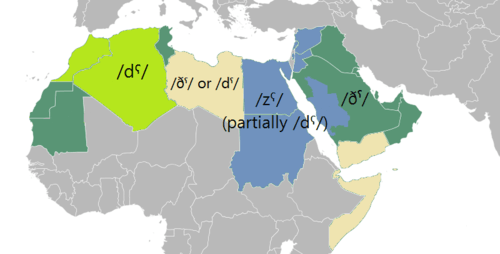

In most Arabic vernaculars ظ ẓāʾ and ض ḍād have been merged quite early.[1] The outcome depends on the dialect. In those varieties (such as Egyptian, Levantine and Hejazi), where the dental fricatives /θ/, /ð/ are merged with the dental stops /t/, /d/, ẓāʾ is pronounced /dˤ/ or /zˤ/ depending on the word; e.g. ظِل is pronounced /dˤilː/ but ظاهِر is pronounced /zˤaːhir/, In loanwords from Classical Arabic ẓāʾ is often /zˤ/, e.g. Egyptian ʿaẓīm (< Classical عظيم ʿaḏ̣īm) "great".[1][2][3]

In the varieties (such as Bedouin and Iraqi), where the dental fricatives are preserved, both ḍād and ẓāʾ are pronounced /ðˤ/.[1][2][4][5] However, there are dialects in South Arabia and in Mauritania where both the letters are kept different but not consistently.[1]

A "de-emphaticized" pronunciation of both letters in the form of the plain /z/ entered into other non-Arabic languages such as Persian, Urdu, Turkish.[1] However, there do exist Arabic borrowings into Ibero-Romance languages as well as Hausa and Malay, where ḍād and ẓāʾ are differentiated.[1]

Statistics

Ẓāʾ is the rarest phoneme of the Arabic language. Out of 2,967 triliteral roots listed by Hans Wehr in his 1952 dictionary, only 42 (1.4%) contain ظ.[6]

In other Semitic languages

In some reconstructions of Proto-Semitic phonology, there is an emphatic interdental fricative, ṱ ([θˤ] or [ðˤ]), featuring as the direct ancestor of Arabic ẓāʾ, while it merged with ṣ in most other Semitic languages, although the South Arabian alphabet retained a symbol for ẓ.

Writing in the Hebrew alphabet

When representing this sound in transliteration of Arabic into Hebrew, it is written as ט׳.

Character encodings

| Preview | ظ | |

|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | ARABIC LETTER ZAH | |

| Encodings | decimal | hex |

| Unicode | 1592 | U+0638 |

| UTF-8 | 216 184 | D8 B8 |

| Numeric character reference | ظ | ظ |

See also

References

- Versteegh, Kees (1999). "Loanwords from Arabic and the merger of ḍ/ḏ̣". In Arazi, Albert; Sadan, Joseph; Wasserstein, David J. (eds.). Compilation and Creation in Adab and Luġa: Studies in Memory of Naphtali Kinberg (1948–1997). pp. 273–286.

- Versteegh, Kees (2000). "Treatise on the pronunciation of the ḍād". In Kinberg, Leah; Versteegh, Kees (eds.). Studies in the Linguistic Structure of Classical Arabic. Brill. pp. 197–199. ISBN 9004117652.

- Retsö, Jan (2012). "Classical Arabic". In Weninger, Stefan (ed.). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 785–786. ISBN 978-3-11-025158-6.

- Ferguson, Charles (1959). "The Arabic koine". Language. 35 (4): 630. doi:10.2307/410601.

- Ferguson, Charles Albert (1997) [1959]. "The Arabic koine". In Belnap, R. Kirk; Haeri, Niloofar (eds.). Structuralist studies in Arabic linguistics: Charles A. Ferguson's papers, 1954–1994. Brill. pp. 67–68. ISBN 9004105115.

- Wehr, Hans (1952). Arabisches Wörterbuch für die Schriftsprache der Gegenwart.