Sidewalk

A sidewalk (American English, Canadian English) or pavement (Australian English, British English, New Zealand English, Singaporean English), also known as a footpath or footway, is a path along the side of a road. Often constructed of concrete but occasionally of asphalt, it is designed for pedestrians.[1] A sidewalk may accommodate moderate changes in grade (height) and is normally separated from the vehicular section by a curb. There may also be a median strip or road verge (a strip of vegetation, grass or bushes or trees or a combination of these) either between the sidewalk and the roadway or between the sidewalk and the boundary.

In some places, the same term may also be used for a paved path, trail or footpath that is not next to a road, for example, a path through a park.

Terminology

The term "sidewalk" is usually preferred in most of North America, along with many other countries worldwide that are not members of the Commonwealth of Nations. The term "pavement" is more common in the United Kingdom,[2] as well as parts of the Mid-Atlantic United States such as Philadelphia and parts of New Jersey.[3][4] Many Commonwealth countries use the term "footpath". The professional, civil engineering and legal term for this in North America is "sidewalk" while in the United Kingdom it is "footway".[5]

In the United States, the term sidewalk is used for the pedestrian path beside a road. "Shared use paths" or "multi-use paths" are available for use by both pedestrians and bicyclists.[6] "Walkway" is a more comprehensive term that includes stairs, ramps, passageways, and related structures that facilitate the use of a path as well as the sidewalk.[7]

In the UK, the term "footpath" is mostly used for paths that do not abut a roadway.[8] The term "shared-use path" is used where cyclists are also able to use the same section of path as pedestrians.[9]

History

_(NYPL_b15279351-105077).tiff.jpg)

Sidewalks have operated for at least 4000 years.[10] The Greek city of Corinth had sidewalks by the 4th-century BCE, and the Romans built sidewalks – they called them sēmitae.[11][12]

However, by the Middle Ages, narrow roads had reverted to being simultaneously used by pedestrians and wagons without any formal separation between the two categories. Early attempts at ensuring the adequate maintenance of foot-ways or sidewalks were often made, as in the 1623 Act for Colchester, but they were generally not very effective.[13]

Following the Great Fire of London in 1666, attempts were slowly made to bring some order to the sprawling city. In 1671, 'Certain Orders, Rules and Directions Touching the Paving and Cleansing The Streets, Lanes and Common Passages within the City of London' were formulated, calling for all streets to be adequately paved for pedestrians with cobblestones. Purbeck stone was widely used as a durable paving material. Bollards were also installed to protect pedestrians from the traffic in the middle of the road.

The British House of Commons passed a series of Paving Acts from the 18th century. The 1766 Paving & Lighting Act authorized the City of London Corporation to establish foot-ways throughout all the streets of London, to pave them with Purbeck stone (the thoroughfare in the middle was generally cobblestone) and to raise them above the street level with curbs forming the separation.[14] The Corporation was also made responsible for the regular upkeep of the roads, including their cleaning and repair, for which they charged a tax from 1766.[15] Another turning point was the construction of Paris's Pont Neuf (1578-1606) which set several trends including wide, raised sidewalks separating pedestrians from the road traffic, plus the first Parisian bridge without houses built on it, and its generous width plus elegant, durable design that immediately became popular for promenading at the beginning of the century that saw Paris take its form renown to this day. It was also a cultural phenomenon because all classes mixed on the new walkways. By the 19th-century large and spacious sidewalks were routinely constructed in European capitals, and were associated with urban sophistication.

In the United States, adjoining property owners must in most situations finance all or part of the cost of sidewalk construction. In a legal case in 1917 involving E. L. Stewart, a former member of the Louisiana House of Representatives and a lawyer in Minden in Webster Parish, the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled that owners must pay whether they wish for the sidewalk to be constructed or not.[16]

Benefits

Transportation

Sidewalks play an important role in transportation, as they provide a safe path for people to walk along that is separated from the motorized traffic. They aid road safety by minimizing interaction between pedestrians and motorized traffic. Sidewalks are normally in pairs, one on each side of the road, with the center section of the road for motorized vehicles.

In rural roads, sidewalks may not be present as the amount of traffic (pedestrian or motorized) may not be enough to justify separating the two. In suburban and urban areas, sidewalks are more common. In town and city centers (known as downtown in North America) the amount of pedestrian traffic can exceed motorized traffic, and in this case the sidewalks can occupy more than half of the width of the road, or the whole road can be reserved for pedestrians, see Pedestrian zone.

Environment

Sidewalks may have a small effect on reducing vehicle miles traveled and carbon dioxide emissions. A study of sidewalk and transit investments in Seattle neighborhoods found vehicle travel reductions of 6 to 8% and CO2 emission reductions of 1.3 to 2.2%[17]

Road traffic safety

Research commissioned for the Florida Department of Transportation, published in 2005, found that, in Florida, the Crash Reduction Factor (used to estimate the expected reduction of crashes during a given period) resulting from the installation of sidewalks averaged 74%.[18] Research at the University of North Carolina for the U.S. Department of Transportation found that the presence or absence of a sidewalk and the speed limit are significant factors in the likelihood of a vehicle/pedestrian crash. Sidewalk presence had a risk ratio of 0.118, which means that the likelihood of a crash on a road with a paved sidewalk was 88.2 percent lower than one without a sidewalk. “This should not be interpreted to mean that installing sidewalks would necessarily reduce the likelihood of pedestrian/motor vehicle crashes by 88.2 percent in all situations. However, the presence of a sidewalk clearly has a strong beneficial effect of reducing the risk of a ‘walking along roadway’ pedestrian/motor vehicle crash.” The study does not count crashes that happen when walking across a roadway. The speed limit risk ratio was 1.116, which means that a 16.1-km/h (10-mi/h) increase in the limit yields a factor of (1.116)10 or 3.[19]

The presence or absence of sidewalks was one of three factors that were found to encourage drivers to choose lower, safer speeds.[20]

On the other hand, the implementation of schemes which involve the removal of sidewalks, such as shared space schemes, are reported to deliver a dramatic drop in crashes and congestion too, which indicates that a number of other factors, such as the local speed environment, also play an important role in whether sidewalks are necessarily the best local solution for pedestrian safety.[21]

In cold weather, black ice is a common problem with unsalted sidewalks. The ice forms a thin transparent surface film which is almost impossible to see, and so results in many slips by pedestrians.

Riding bicycles on sidewalks is discouraged since some research shows it to be more dangerous than riding in the street.[22] Some jurisdictions prohibit sidewalk riding except for children. In addition to the risk of cyclist/pedestrian collisions, cyclists face increase risks from collisions with motor vehicles at street crossings and driveways. Riding in the direction opposite to traffic in the adjacent lane is especially risky.[23]

Health

Since residents of neighborhoods with sidewalks are more likely to walk, they tend to have lower rates of cardiovascular disease, obesity, and other health issues related to sedentary lifestyles.[24] Also, children who walk to school have been shown to have better concentration.[25]

Social uses

Some sidewalks may be used as social spaces with sidewalk cafes, markets, or busking musicians, as well as for parking for a variety of vehicles including cars, motorbikes and bicycles.

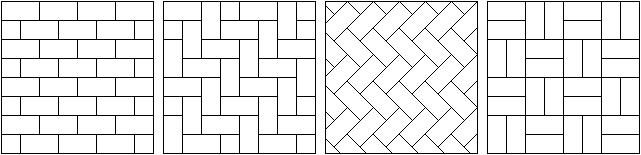

Construction

Contemporary sidewalks are most often made of concrete in North America, while tarmac, asphalt, brick, stone, slab and (increasingly) rubber are more common in Europe.[26] Different materials are more or less friendly environmentally: pumice-based trass, for example, when used as an extender is less energy-intensive than Portland cement concrete or petroleum-based materials such as asphalt or tar-penetration macadam. Multi-use paths alongside roads are sometimes made of materials that are softer than concrete, such as asphalt.

Wood

In the 19th century and early 20th century, sidewalks of wood were common in some North American locations. They may still be found at historic beach locations and in conservation areas to protect the land beneath and around, called boardwalks.

Brick

Brick sidewalks are found in some urban areas, usually for aesthetic purposes. Brick sidewalks are generally consolidated with brick hammers, rollers, and sometimes motorized vibrators.

Stone

Stone slabs called flagstones or flags are sometimes used where an attractive appearance is required, as in historic town centers.

Stone and concrete pavers

Pre-cast concrete pavers are used for sidewalks, often colored or textured to resemble stone. Sometimes cobblestones are used, though they are generally considered too uneven for comforable walking.

- Installation of crushed stone underlayment for drainage

- Installation of paver blocks

Concrete

In the United States and Canada, the most common type of sidewalk consists of a poured concrete ribbon, examples of which from as early as the 1860s can be found in good repair in San Francisco, and stamped with the name of the contractor and date of installation. When quantities of Portland cement were first imported to the United States in the 1880s, its principal use was in the construction of sidewalks.[27]

Today, most sidewalk ribbons are constructed with cross-lying strain-relief grooves placed or sawn at regular intervals typically 5 feet (1.5 m) apart. This partitioning, an improvement over the continuous slab, was patented in 1924 by Arthur Wesley Hall and William Alexander McVay, who wished to minimize damage to the concrete from the effects of tectonic and temperature fluctuations, both of which can crack longer segments.[28] The technique is not perfect, as freeze-thaw cycles (in cold-weather regions) and tree root growth can eventually result in damage which requires repair.

In highly variable climates which undergo multiple freeze-thaw cycles, the concrete blocks will be separated by expansion joints to allow for thermal expansion without breakage. The use of expansion joints in sidewalks may not be necessary, as the concrete will shrink while setting.[29]

Tarmac and asphalt

In the United Kingdom, Australia and France suburban sidewalks are most commonly constructed of tarmac. In urban or inner-city areas sidewalks are most commonly constructed of slabs, stone, or brick depending upon the surrounding street architecture and furniture.

Gallery

Old sidewalk with granite curb in Kutná Hora, Czech Republic

Old sidewalk with granite curb in Kutná Hora, Czech Republic.jpg)

Sidewalk market, Speightstown, Barbados

Sidewalk market, Speightstown, Barbados Overspill parking on the sidewalk in Moscow, Russia

Overspill parking on the sidewalk in Moscow, Russia Sidewalk with trees in Oak Park, Illinois

Sidewalk with trees in Oak Park, Illinois- Sidewalk with a planted rain garden in the "tree lawn" or "road verge" zone

- Sidewalk blocked with motorcycles in Iran

- Sidewalk in Nishapur, near Mausoleum of Omar Khayyam

Sidewalk in Benoni, South Africa

Sidewalk in Benoni, South Africa- Bicycle parking

"Sidewalk closed" sign in Miami Beach urges crossing street to other sidewalk

"Sidewalk closed" sign in Miami Beach urges crossing street to other sidewalk Sidewalk in Belleair Bluffs, FL

Sidewalk in Belleair Bluffs, FL A sidewalk in Montreal, Quebec

A sidewalk in Montreal, Quebec

See also

References

- Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 594. ISBN 9780415252256.

- "Parking on pavements". Lewisham Council. Archived from the original on 2010-10-04. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

Why is pavement parking a problem? Pavements are constructed and provided for pedestrian use. Vehicles parked on pavements are: a hazard to pedestrians causing an obstruction which may result in them having to step off the pavement onto the highway thus putting themselves in danger...

- Cassidy, Frederic Gomes, and Joan Houston Hall (eds). (2002) Dictionary of American Regional English. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Allan A. Metcalf (2000). How We Talk: American Regional English Today. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 90. ISBN 0-618-04362-4.

- "Highways Act 1980 – Interpretation Section 329". Archived from the original on 2011-02-06.

“footway” means a way comprised in a highway which also comprises a carriageway, being a way over which the public have a right of way on foot only

- "Part II of II: Best Practices Design Guide - Sidewalk2 - Publications - Bicycle and Pedestrian Program - Environment - FHWA". www.fhwa.dot.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-11-29.

- "Walkway". Compact Oxford English Dictionary.

- "Inclusive mobility". Department for Transport. Archived from the original on 2010-11-22. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

The distinction between a footway and a footpath is that a footway is the part of a highway adjacent to, or contiguous with, the roadway on which there is a public right of way on foot. A footpath is not adjacent to a public roadway. Where reference is made to one, it can generally be regarded as applying to the other for design purposes

CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) - "Highways Act 1980 – Interpretation Section 329". Archived from the original on 2011-02-06.

"cycle track” means a way constituting or comprised in a highway, being a way over which the public have the following, but no other, rights of way, that is to say, a right of way on pedal cycles [F3 (other than pedal cycles which are motor vehicles within the meaning of F4 the Road Traffic Act 1988 with or without a right of way on foot

-

Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Renia Ehrenfeucht (2009). Sidewalks: Conflict and Negotiation Over Public Space. MIT Press. p. 15. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

The first sidewalks appeared around 2000 to 1990 B.C. [...] in central Anatolia (modern Turkey) [...].

- Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Renia Ehrenfeucht (2009). Sidewalks: Conflict and Negotiation Over Public Space. MIT Press. p. 15.

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/semita#Latin semita

- "Georgian Colchester". British History. Archived from the original on 2011-12-28. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

Bad paving and obstructions were frequently reported to the justices under a paving Act of 1623, but the borough chamberlain, workhouse corporation, and parish officers failed to discharge their responsibilities and the small fines for neglect were ineffective. Enforcement of the Act by the borough justices ceased when the charter lapsed in 1741 and by 1750 the streets were so ruinous that a new Act was obtained, which perpetuated the responsibility of justices to enforce the regulations.

- Linda Clarke (2002). Building Capitalism (Routledge Revivals): Historical Change and the Labour Process in the Production of Built Environment. Routledge. p. 115.

- "city street scene manual" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-15. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- Town of Minden v. Stewart et al. Southern Reporter, Vol. 77. November 26, 1917. pp. 118–121. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- "Research Note: An Assessment of Urban Form and Pedestrian and Transit Improvements as an Integrated GHG Reduction Strategy" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. April 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-18.

-

Gan, Albert; Joan Shen; Adriana Rodriquez (2005). "Update of Florida Crash Reduction Factors and Countermeasures to Improve the Development of District Safety Improvement Projects" (PDF). State of Florida DOT. BD015-04. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-04-10. Retrieved 2008-03-24. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) -

McMahon, Patrick J.; Charles V. Zegeer; Chandler Duncan; Richard L. Knoblauch; J. Richard Stewart; Asad J. Khattak (2002). "AN ANALYSIS OF FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO "WALKING ALONG ROADWAY" CRASHES, RESEARCH STUDY AND GUIDELINES FOR SIDEWALKS AND WALKWAYS" (PDF). Federal Highway Administration. FHWA-RD-01-101. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-04-10. Retrieved 2008-03-24. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - John N. Ivan, Norman W. Garrick and Gilbert Hanson (November 2009). DESIGNING ROADS THAT GUIDE DRIVERS TO CHOOSE SAFER SPEEDS. Connecticut Transportation Institute.

- "Do you take unnecessary risks behind the wheel?". Which?. 2011-01-05. Archived from the original on 2012-03-12. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

The town of Drachten removed most of its street furniture, signs and markings in 2003 and recorded a dramatic fall in accidents and traffic congestion as a result

- Lisa Aultman-Hall and Michael F. Adams, Jr. (1998). "Sidewalk Bicycling Safety Issues". Transportation Research Record (1636).

- "Bicycle sidepaths: Crash risks and liability exposure: Evidence from the research literature". 8 December 2010. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- "Crimes of the Heart". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on August 10, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- "The Link Between Kids Who Walk or Bike to School and Concentration". The Atlantic Cities. Archived from the original on February 7, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- Webster, George (2011-10-13). "Green sidewalk makes electricity one footstep at a time". CNN.

- Robert W. Lesley. "What Cement Users Owe To The Public". The Cement age: a magazine devoted to the uses of cement. 2 (9): 652.

- Mario Theriault, Great Maritime Inventions – 1833–1950, Goose Lane Editions, 2001, p. 73

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-05-21. Retrieved 2014-05-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sidewalks. |

- Los Alamos Walkability Advocacy Group

- PEDS a member-based advocacy group dedicated to making metro Atlanta safe and accessible for all pedestrians.

- Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center (PBIC), a U.S.A.-based clearinghouse for information for pedestrians (including transit users) and bicyclists.