Triptan

Triptans are a family of tryptamine-based drugs used as abortive medication in the treatment of migraines and cluster headaches. This drug class was first introduced in the 1990s. While effective at treating individual headaches, they do not provide preventive treatment and are not considered a cure. They are not effective for the treatment of tension–type headache,[1] except in persons who also experience migraines.[2] They may be effective in disabling tension–type headaches, which exist on a spectrum of migraine.[2] Triptans do not relieve other kinds of pain.

| Triptans | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

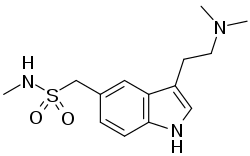

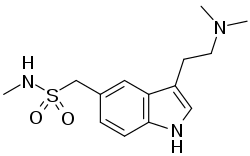

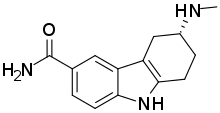

Chemical structure of sumatriptan, the prototypical triptan | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | Migraine, cluster headache |

| ATC code | N02CC |

| Biological target | 5-HT1B receptor, 5-HT1D receptor |

| In Wikidata | |

The drugs of this class act as agonists for serotonin 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors at blood vessels and nerve endings in the brain. The first clinically available triptan was sumatriptan, which has been marketed since 1991. Triptans have largely replaced ergotamines, an older class of medications used to relieve migraine and cluster headaches.[3]

Medical uses

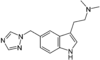

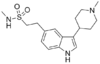

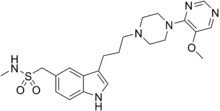

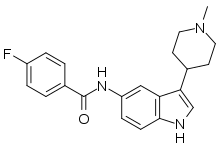

| sumatriptan | rizatriptan | naratriptan |

|  |  |

| eletriptan | donitriptan | almotriptan |

| frovatriptan | avitriptan | zolmitriptan |

|  |  |

| LY-334370 | GR-46611[4][5] | |

| ||

Migraine

Triptans are used for the treatment of severe migraine attacks or those that do not respond to NSAIDs[6] or other over-the-counter drugs.[7] Triptans are a mid-line treatment suitable for many migraineurs with typical attacks. They may not work for atypical or unusually severe migraine attacks, transformed migraine, or status (continuous) migrainosus.

Triptans are highly effective, reducing the symptoms or aborting the attack within 30 to 90 minutes in 70–80% of patients.

A test measuring a person's skin sensitivity during a migraine may indicate whether the individual will respond to treatment with triptans.[8] Triptans are most effective in those with no skin sensitivity; with skin sensitivity, it is best to take triptans within twenty minutes of the headache's onset.

Oral rizatriptan and nasal zolmitriptan are the most used triptans for migraines in children.[9]

Cluster headache

Triptans are effective for the treatment of cluster headache. This has been demonstrated for subcutaneous sumatriptan and intranasal zolmitriptan, the former of which is more effective according to a 2013 Cochrane review. Tablets were not considered appropriate in this review.[10]

Altitude sickness

A single randomized controlled trial found that sumatriptan may be able to prevent altitude sickness.[11]

Available forms

All marketed triptans are available in oral form; some in form of sublingual tablets.[12] Sumatriptan and zolmitriptan are also available as nasal sprays.[12][13] For sumatriptan, a number of other application forms are marketed: suppositories, a subcutaneous injection,[12] an iontophoretic transdermal patch, which uses low voltage controlled by a pre-programmed microchip to deliver a single dose of sumatriptan through the skin within 30 minutes;[14] a drug-device combination containing sumatriptan powder that is "breath powered" allowing the user to blow sumatriptan powder in to their nostrils;[15] as well as a needle-free injection system that works with air pressure.[16]

Contraindications

All triptans are contraindicated in patients with cardiovascular diseases (coronary spasms, symptomatic coronary artery disease, after a heart attack or stroke, uncontrolled hypertension, Raynaud's disease, peripheral artery disease). Most triptans are also contraindicated during pregnancy and breastfeeding and for patients younger than 18; but sumatriptan and zolmitriptan nasal sprays are also approved for youths over 12.[1] In spite of expert opinion and evidence to the contrary, the FDA and some other drug governance bodies have stated that monoamine oxidase inhibitors are contraindicated for sumatriptan, zolmitriptan and rizatriptan,[17][18] and combination with ergot alkaloids such as ergotamine for all substances.[12]

At least two triptans (sumatriptan and rizatriptan) have been listed under the unacceptable medication by the Canadian Blood Services as a potential risk to the recipient; hence, donors are required not to have taken the medication for the last 72 hours.

Adverse effects

Triptans have few side effects if used in correct dosage and frequency. The most common adverse effect is recurrence of migraine. A systematic review found that "rizatriptan 10 mg was the only triptan with a recurrence rate greater than that of placebo".[19]

There is a theoretical risk of coronary spasm in patients with established heart disease, and cardiac events after taking triptans may rarely occur.[20]

Interactions

Combination of triptans with other serotonergic drugs such as ergot alkaloids, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) or St John's wort has been alleged to induce symptoms of a serotonin syndrome (a syndrome of changes in mental status, autonomic instability, neuromuscular abnormalities, and gastrointestinal symptoms),[1][12] whereas scientific studies indicate there is no potential for life-threatening serotonin syndrome in patients taking triptans and SSRI or SNRIs at the same time, although the FDA has officially stated otherwise.[21][22][23][24][25][26] Combining triptans with ergot alkaloids is contraindicated because of the danger of coronary spasms.[12]

In a study from Harvard Medical School and the University of Florida College of Medicine involving 47,968 patients and published on 26 February 2018, concomitant use of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor for depression with a triptan for migraine did not demonstrate an increased risk of the serotonin syndrome.[27]

Pharmacokinetic interactions (for example, mediated by CYP liver enzymes or transporter proteins) are different for the individual substances; for most triptans, they are mild to absent. Eletriptan blood plasma levels are increased by strong inhibitors of CYP3A4, and frovatriptan levels by CYP1A2 inhibitors such as fluvoxamine.[12]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Their action is attributed to their agonist[28] effects on serotonin 5‑HT1B and 5‑HT1D receptors in blood vessels (causing their constriction) and nerve endings in the brain, and subsequent inhibition of pro-inflammatory neuropeptide release, including CGRP and substance P. Triptans are selective agents for 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D[28] and have low or even no affinity for other types of 5-HT receptors.[18]

5-HT receptors are classified into seven different families named 5-HT1 to 5-HT7. All receptors are G protein coupled receptors with seven transmembrane domains with the one exception of 5-HT3 receptor which is a ligand gated ion channel. There is a high homology in the amino acid sequence within each family. Each family couples to the same second messenger systems. Subtypes of 5-HT1 are the 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT1E and 5-HT1F receptors. All 5-HT1D receptors are coupled to inhibition of adenylate cyclase. 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors have been difficult to distinguish on a pharmacological basis. After cloning two distinct genes for 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D receptors, a better insight into distribution and expression in different tissues was gained, except in brain tissue where they are overlapping in several areas.[29]

Most mammalian species, including humans, have 5-HT1D binding sites widely distributed throughout the central nervous system. 5-HT1D receptors are found in all areas of the brain but they differ in quantity at each area.[30] An important initiator of head pain is suggested to be the activation of trigeminovascular afferent nerves which upon activation releases neuropeptides such as CGRP, substance P and neurokinin A. Also they are thought to promote neurogenic inflammatory response important for sensitization of sensory afferents, and also transmission and generation of head pain centrally. 5-HT1D has been found responsible for inhibition of neurogenic inflammation upon administration with sumatriptan and other related compounds that act on prejunctional 5-HT1D receptors.[29]

All triptans, like the older drug dihydroergotamine, have agonistic effects on the 5-HT1D receptor. Comparison of sumatriptan and dihydroergotamine showed that dihydroergotamine has high affinity and sumatriptan has medium affinity for 5-HT1D.[28] Triptans have at least three modes of action. These antimigraine mechanisms are:

- vasoconstriction of pain producing intra cranial extracerebral vessels by a direct effect on vascular smooth muscle. Sumatriptan and rizatriptan have been shown to cause vasoconstriction in the human middle meningeal arteries.

- inhibition of vasoactive neuropeptide release by trigeminal terminals innervating intracranial vessels and the dura mater. The trigeminocervical complex has 5-HT1D receptors that bind dihydroergotamine and triptans in humans. Rizatriptan has been shown to block dural vasodilation and plasma protein extravation by inhibiting the release of CGRP via activation of receptors on preganglionic trigeminal sensory nerver terminals. Sumatriptan is shown to inhibit potassium stimulated CGRP secretion from cultured trigeminal neurons in dose dependant manner and may also inhibit the release of substance P.

- inhibition of nociceptive neurotransmission within the trigeminocervical complex in the brainstem and upper cervical spinal column. Rizatriptan has central trigeminal antinociceptive activity.

Other possibilities of triptans in antimigraine effects are modulation of nitric oxide dependent signal transduction pathways, nitric oxide scavenging in the brain, and sodium dependent cell metabolic activity.[31][28]

Pharmacokinetics

Triptans have a wide variety of pharmacokinetic properties. Bioavailability is between 14% and 70%, biological half-life (T1/2) is between 2 and 26 hours. Their good ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and the rather long half life of some triptans may result in lower frequencies of migraine recurrence.[18][32][33][34]

Comparison

| Drug | Brand | Company | Receptor agonist | 5-HT1D affinity (pKI in nM)[35] | Bioavailability (%) | log DpH 7.4 | Tmax (h) | T1/2 (h) | Metabolism | Dose (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sumatriptan | Imitrex | Glaxo Smith Kline | 5-HT1B/D | 7.9–8.5 | 14–17 | –1.3 | 2–2.5 | 2.5 | MAO-A | 25 50 100 |

| Zolmitriptan | Zomig | Grünenthal[36] | 5-HT1B/D | 9.2 | 40 | –0.7 | 1.5–2 | 2–3 | MAO-A CYP1A2 |

2.5 5 |

| Naratriptan | Amerge | Glaxo Smith Kline | 5-HT1B/D | 8.3 | 70 | –0.2 | 2–3 | 6 | many CYPs MAO-A |

1 2.5 |

| Rizatriptan | Maxalt | Merck | 5-HT1B/D | 7.7 | 45 | –0.7 | 1–1.5 | 2–2.5 | MAO-A | 5 10 |

| Almotriptan | Axert | Almirall-Prodesfarma | 5-HT1B/D 5-HT1F |

7.8 | 70 | +0.35 | 2.5 | 3.6 | CYP2D6 CYP3A4 MAO-A |

6.25 12.5 |

| Eletriptan | Relpax | Pfizer | 5-HT1B/D 5-HT1F[37] |

8.9 | 50 | +0.5 | 1–2 | 3.6–5.5 | CYP3A4 | 20 40 80 |

| Frovatriptan | Frova | Vernalis | 5-HT1B/D | 8.4 | 24–30 | 2–4 | 26 | CYP1A2 | 2.5 |

Zolmitriptan is different from the other triptans because it is converted to an active N-desmethyl metabolite which has higher affinity for the 5-HT1D and 5-HT1B receptors; both substances have a biological half-life of 2 to 3 hours.[18] In studies, newer triptans are mostly compared to sumatriptan.[17] They are better than sumatriptan for their longer half-life in plasma and higher oral bioavailability,[38] but have a higher potential for central nervous side effects.[1]

Donitriptan and avitriptan were never marketed.

History

The history of triptans began with the proposed existence of then unknown serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT). In the late 1940s two groups of investigators, one in Italy and the other in the United States, identified a substance that was called serotonin in the US and enteramine in Italy. In the early 1950s it was confirmed that both substances were the same. In the mid-1950s it was proposed that serotonin had a role as a neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS) of animals. Investigations of the mechanism of action were not very successful as experimental techniques were lacking.[38]

Later in the 1960s, studies showed that vasoconstriction caused by 5-HT, noradrenaline and ergotamine could reduce migraine attacks. Patrick P.A. Humphrey among others at Glaxo started researching the 5-HT receptor to discover a more direct 5-HT agonist with fewer side effects.

They continued developing and working on a desirable action on 5-HT by 5-HT1 receptor activation for an anti-migraine drug. Continued work led to the development of sumatriptan, now known as the first 5-HT1 agonist, selective for the 5-HT1D/B receptors and also the 5-HT1F receptor with less affinity. By 1991 sumatriptan became available in clinical use in the Netherlands and in the US in 1993. However, there was always a debate about its mechanism of action, and it still remains unclear today. Later, Mike Moskowitz proposed a theory about "neuronal extravasation", and this was the first clue that sumatriptan might have a direct neuronal effect in migraine attacks.[39]

Sumatriptan became a prototype for other triptans that have been developed for improved selectivity for the 5-HT1D/B receptors.[38]

Society and culture

Legal status

These drugs have been available only by prescription (US, Canada and UK), but sumatriptan became available over-the-counter in the UK in June 2006.[40] The brand name of the OTC product in the UK is Imigran Recovery. The patent on Imitrex STATDose expired in December 2006, and injectable sumatriptan became available as a generic formula in August 2008. Sumavel Dosepro is a needle-free delivery of injectable sumatriptan that was approved in the US by the FDA in July 2009.[16] Sumatriptan became available as a generic in the US in late 2009. It used to be sold over-the-counter in Romania under the Imigran brand; however, as of August 2014 prescription is required. Zecuity, a sumatriptan transdermal patch, was approved by the US FDA in January 2013.[14] The sumatriptan nasal powder was approved by the FDA in January 2016 and became available in the U.S. May 2016.[41] Naritriptan is available OTC in Germany and Brazil.

References

- Notes

- Mutschler, Ernst; Gerd Geisslinger; Heyo K. Kroemer; Sabine Menzel; Peter Ruth (2013). Arzneimittelwirkungen (in German) (10 ed.). Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. pp. 233–4. ISBN 978-3-8047-2898-1.

- Green, Mark W. (2015). "Overview of Migraine: Recognition, Diagnosis, and Pathophysiology". In Diamond, Seymour; Cady, Roger K.; Diamond, Merle L.; Green, Mark W.; Martin, Vincent T. (eds.). Headache and Migraine Biology and Management. Academic Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780128009017. Archived from the original on 2018-05-06 – via GoogleBooks.

- Antonaci, Fabio; Ghiotto, Natascia; Wu, Shizheng; Pucci, Ennio; Costa, Alfredo (2016). "Recent advances in migraine therapy". SpringerPlus. 5: 637. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-2211-8. ISSN 2193-1801. PMC 4870579. PMID 27330903.

- Amireault, Pascal; Bayard, Elisa; Launay, Jean-Marie; Sibon, David; Le Van Kim, Caroline; Colin, Yves; Dy, Michel; Hermine, Olivier; Côté, Francine (2013). "Serotonin is a Key Factor for Mouse Red Blood Cell Survival". PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e83010. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...883010A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083010. PMC 3866204. PMID 24358245.

- "3-[3-(2-Dimethylaminoethyl)-1H-indol-5-yl]-N-(4-methoxybenzyl)acrylamide". PubChem. Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- Brandes JL, Kudrow D, Stark SR, et al. (2007). "Sumatriptan-naproxen for acute treatment of migraine: a randomized trial". JAMA. 297 (13): 1443–1454. doi:10.1001/jama.297.13.1443. PMID 17405970.

- Lipton RB, Baggish JS, Stewart WF, Codispoti JR, Fu M (2000). "Efficacy and safety of acetaminophen in the treatment of migraine: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, population-based study". Arch. Intern. Med. 160 (22): 3486–92. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.22.3486. PMID 11112243.

- Burstein, R; Collins, B; Jakubowski, M (2004). "Defeating migraine pain with triptans: A race against the development of cutaneous allodynia". Annals of Neurology. 55 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1002/ana.10786. PMID 14705108.

- Eiland, L. S.; Hunt, M. O. (2010). "The use of triptans for pediatric migraines". Paediatr Drugs. 12 (6): 379–389. doi:10.2165/11532860-000000000-00000. PMID 21028917. S2CID 11187764.

- Law, S; Derry, S; Moore, R. A. (2013). "Triptans for acute cluster headache". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD008042. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008042.pub3. PMC 4170909. PMID 24353996.

- Jafarian S, Gorouhi F, Salimi S, Lotfi J (2007). "Sumatriptan for prevention of acute mountain sickness: randomized clinical trial". Ann. Neurol. 62 (3): 273–7. doi:10.1002/ana.21162. PMID 17557349.

- Haberfeld, H, ed. (2016). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. Cofact.

- "Imitrex Nasal Spray package insert" (PDF). GlaxoSmithKline prescribing information. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- Pierce, Mark; Marbury, Thomas; O'Neill, Carol; Siegel, Steven; Du, Wei; Sebree, Terri (2009-06-01). "Zelrix: a novel transdermal formulation of sumatriptan". Headache. 49 (6): 817–825. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01437.x. ISSN 1526-4610. PMID 19438727.

- "Onzetra Xsail Approved as Migraine Treatment". pharmacytimes.com. February 3, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- "Zogenix, Inc. - Therapeutic Solutions for CNS Disorders and Rare Disease". www.zogenix.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- Ferrari, M. D.; Goadsby, P. J.; Roon, K. I.; Lipton, R. B. (2002). "Triptan (serotonin, 5-HT1D/1B agonists) in migraine: detailed results and methods of a meta-analysis of 53 trials". Cephalalgia. 22 (8): 633–658. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00404.x. PMID 12383060.

- Brunton, L., Lazo, J., Parker, K. (2006). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 305–308.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Pascual J, Mateos V, Roig C, Sanchez-Del-Rio M, Jiménez D (2007). "Marketed oral triptans in the acute treatment of migraine: a systematic review on efficacy and tolerability". Headache. 47 (8): 1152–68. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00849.x. PMID 17883520.

- Dahlöf CG, Mathew N (1998). "Cardiovascular safety of 5HT1B/1D agonists--is there a cause for concern?". Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache. 18 (8): 539–45. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.1998.1808539.x. PMID 9827245.

- Shapiro, Robert E.; Tepper, Stewart J. (2007). "The Serotonin Syndrome, Triptans, and the Potential for Drug–Drug Interactions". Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 47 (2): 266–9. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00691.x. PMID 17300366.

- Evans, Randolph W.; Tepper, Stewart J.; Shapiro, Robert E.; Sun-Edelstein, Christina; Tietjen, Gretchen E. (2010). "The FDA Alert on Serotonin Syndrome With Use of Triptans Combined With Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors or Selective Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors: American Headache Society Position Paper". Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 50 (6): 1089. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01691.x. PMID 20618823.

- Gillman (2010). "Triptans, serotonin agonists, and serotonin syndrome (serotonin toxicity): a review". Headache. 50 (2): 264–272. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01575.x.

- Evans, R. W. (2007). "The FDA alert on serotonin syndrome with combined use of SSRIs or SNRIs and triptans: an analysis of the 29 case reports". MedGenMed : Medscape General Medicine. 9 (3): 48. PMC 2100123. PMID 18092054.

- Wenzel, R. G.; Tepper, S; Korab, W. E.; Freitag, F (2008). "Serotonin syndrome risks when combining SSRI/SNRI drugs and triptans: is the FDA's alert warranted?". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 42 (11): 1692–6. doi:10.1345/aph.1L260. PMID 18957623.

- US Food and Drug Administration (2006-07-19). "Information for Healthcare Professionals". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 2008-02-19. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- Orlova, Yulia; Rizzoli, Paul; Loder, Elizabeth (26 February 2018). "Association of Coprescription of Triptan Antimigraine Drugs and Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor or Selective Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants With Serotonin Syndrome". JAMA Neurology. 75 (5): 566–572. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.5144. PMC 5885255. PMID 29482205.

- Tepper, S. J.; Rapoport, A. M.; Sheftell, F. D. (2002). "Mechanisms of action of the 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists". Archives of Neurology. 59 (7): 1084–1088. doi:10.1001/archneur.59.7.1084. PMID 12117355.

- Hamel, E. (1999). "The biology of serotonin receptors: focus on migraine pathophysiology and treatment". Can J Neurol Sci. 26 Suppl 3 (3). 26 Suppl 3:S2–6. doi:10.1017/s0317167100000123. PMID 10563226.

- Lowther, S. (1992). "The distribution of 5HT1D and 5HT1E binding sites in human brain". Eur J Pharmacol. 222 (1): 137–42. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(92)90473-h. PMID 1468490.

- Goadsby, P. J. (1998). "Serotonin 5HT1B/1D receptor agonists in migraine - Comparative pharmacology and its therapeutic implications". CNS Drugs. 10 (4): 271–286. doi:10.2165/00023210-199810040-00005.

- Bigal, M. E.; Bordini, C. A.; Antoniazzi, A. L.; Speciali, J. G. (2003). "The triptan formulations: a critical evaluation". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 61 (2A): 313–320. doi:10.1590/s0004-282x2003000200032. PMID 12806521.

- Armstrong, S. C.; Cozza, K. L. (2002). "Triptans". Psychosomatics. 43 (6): 502–504. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.43.6.502. PMID 12444236.

- Mathew, N. T.; Loder, E. W. (2005). "Evaluating the triptans". The American Journal of Medicine Supplements. 118 (1): 28–35. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.017. PMID 15841885.

- Deleu, D.; Hanssens Y. (2000). "Current and emerging second-generation triptans in acute migraine therapy: a comparative review". J Clin Pharmacol. 40 (7): 687–700. doi:10.1177/00912700022009431. PMID 10883409.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "AstraZeneca enters agreement with Grünenthal to divest rights to migraine treatment Zomig". www.astrazeneca.com. Archived from the original on 2018-03-22. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- "Relpax – 20 mg and 40 mg". Archived from the original on 2004-06-20. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- Lippincott, W. W., Lemke, T. L., Williams, D. A., Roche, V. F., Zito, S. W. (2013). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 368–376.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Humphrey, P. P. (2007). "The discovery of a new drug class for the acute treatment of migraine". Headache. 47 (Suppl 1): S10–19. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00672.x. PMID 17425704.

- "Pharmacies to sell migraine drug". BBC NEWS. 2006-05-19. Archived from the original on 2006-09-24. Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- "Avanir's press release: FDA approves Onzetra". Avanir Pharmaceuticals. January 28, 2016. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- Sources

- Tepper S. J.; Rapoport A. M. (1999). "The triptans - A summary". CNS Drugs. 12 (5): 403–417. doi:10.2165/00023210-199912050-00007.