Traditional fishing boat

Traditionally, many different kinds of boats have been used as fishing boats to catch fish in the sea, or on a lake or river. Even today, many traditional fishing boats are still in use. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), at the end of 2004, the world fishing fleet consisted of about 4 million vessels, of which 2.7 million were undecked (open) boats. While nearly all decked vessels were mechanised, only one-third of the undecked fishing boats were powered, usually with outboard engines. The remaining 1.8 million boats were traditional craft of various types, operated by sail and oars.[1]

This article is about the boats used for fishing that are or were built from designs that existed before engines became available.

Overview

Early fishing vessels included rafts, dugout canoes, reed boats, and boats constructed from a frame covered with hide or tree bark, such as coracles.[2] The oldest boats found by archaeological excavation are dugout canoes dating back to the Neolithic Period around 7,000-9,000 years ago. These canoes were often cut from coniferous tree logs, using simple stone tools.[2][3] A 7000-year-old sea going boat made from reeds and tar has been found in Kuwait.[4] These early vessels had limited capability; they could float and move on water, but were not suitable for use any great distance from the shoreline. They were used mainly for fishing and hunting.

The development of fishing boats took place in parallel with the development of boats built for trade and war. Early navigators began to use animal skins or woven fabrics for sails. Affixed to a pole set upright in the boat, these sails gave early boats more range, allowing voyages of exploration

According to the FAO, at the end of 2004, the world fishing fleet included 1.8 million traditional craft of various types which were operated by sail and oars.[5] These figures for small fishing vessels are probably under reported. The FAO compiles these figures largely from national registers. These records often omit smaller boats where registration is not required or where fishing licences are granted by provincial or municipal authorities.[5] Indonesia reportedly has about 700,000 current fishing boats, 25 percent of which are dugout canoes, and half of which are without motors.[6] The Philippines have reported a similar number of small fishing boats.

Traditional fishing boats are usually characteristic of the stretch of coast along which they operate. They evolve over time to meet the local conditions, such as the materials available locally for boat building, the type of sea conditions the boats will encounter, and the demands of the local fisheries.

These fishing boats in Gambia conform to a local design.

These fishing boats in Gambia conform to a local design. These fishing boats conform to a different local design in Vietnam

These fishing boats conform to a different local design in Vietnam Fishing boats in Thailand, at Surat Thani, follow this style

Fishing boats in Thailand, at Surat Thani, follow this style Fishing boats in Thailand, at Bang Sen, follow another style

Fishing boats in Thailand, at Bang Sen, follow another style

Artisan fishing is small-scale commercial or subsistence fishing, particularly practices involving coastal or island ethnic groups using traditional fishing techniques and traditional boats. This may also include heritage groups involved in customary fishing practices. Artisan fishers usually use small traditional fishing boats that are open (undecked) and have sails; these boats use little to no mechanised or electronic gear. Large numbers of artisan fishing boats are still in use, particularly in developing countries with long productive marine coastlines.

Rafts

A raft is a structure with a flat top that floats. It is the most basic boat design, characterised by the absence of a hull. The classic raft is constructed by lashing several logs, placed side by side, to two or more additional logs placed transverse to the others. In many Asian countries, the rafts are similarly constructed using bamboo.

In shallow waters, rafts can be punted with a push pole. They can be used as stealthy platforms for fishing shallow waters around lakes. In sheltered coastal waters, anchored or drifting rafts can become effective fish aggregating devices. Payaos were traditional bamboo rafts used in Southeast Asia as aggregating device. Fishermen on the top of the raft used handlines to catch tuna.[7]

Pontoon boats, and to some degree the punt, can be viewed as modern derivatives of rafts.

Reed boats

Boats, rafts and even small floating islands have been made from reeds. Reed rafts can be distinguished from reed boats, since the rafts are not made watertight.[8]

The earliest known boat made with reeds (and tar) is a 7000-year-old sea going boat found in Kuwait.[4]

The Uros are an indigenous people pre-dating the Incas. They live, still today, on man-made floating islands scattered across Lake Titicaca. These islands are constructed from totora reeds.[9] Each floating island supports between three and ten houses, also built of reeds.[10] The Uros also build their boats from bundled dried reeds.[9] These days some Uros boats, used for fishing and hunting seabirds, have motors.

Reed boats were constructed in Easter Island with a markedly similar design to those used in Peru.[11] Apart from Peru and Bolivia, reed boats are still used in Ethiopia[12] and were used until recently in Corfu.[13]

Coracles

Coracles are light boats shaped like a bowl, typically with a frame of woven grass or reeds, or strong saplings covered with animal hides.[14] The keel-less, flat bottom evenly spreads the weight across the structure reducing the required depth of water often to only a few inches. Coracles have been used, and to a degree are still used, in India, Vietnam, Iraq, Tibet, North America and Britain.[15]

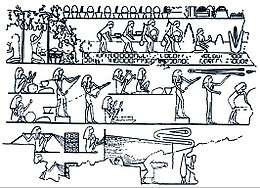

Coracles in Iraq are called "quffa." Their history goes back to antiquity where they appear on Assyrian-era reliefs sculpted between 600 and 900 BC. These reliefs are now in the British Museum. Herodotus visited Babylon in the 5th century BC, and wrote a long description of the coracles he encountered there. Traditionally, quffa were framed with willow or juniper and covered with hides or reeds. The outside was then coated with hot bitumen for waterproofing, although the inside could also be coated for larger vessels. These coracles have been in continuous use on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, particularly around Baghdad, through the 1970s. Some of the Iraqi coracles are very large, with the largest reaching up to 5.5 metres (18 ft) in diameter and being able to carry up to 5 tons.[16]

Coracles are known to have been in use in Britain in 49 BC when Julius Caesar encountered them.[17] They are still used in Wales, where they were traditionally framed with split and interwoven willow rods, tied with willow bark. The outer layer was an animal skin, such as horse or bullock hide, with a thin layer of tar for waterproofing. Today tarred calico or canvas, or simply fiberglass can be used.[18][19] Different Welsh rivers have their own designs, tailored to the flow of the river. The Teifi coracle, for instance, is flat-bottomed, as it is designed to negotiate shallow rapids, common on the river in the summer, while the Carmarthen coracle is rounder and deeper, because it is used in tidal waters on the Tywi, where there are no rapids.[20]

Coracles can be effective fishing vessels. When operated skilfully, they hardly disturb the water or the fish. Welsh coracle fishing is performed by two men, each seated in his coracle and with one hand holding the net while with the other he plies his paddle. When a fish is caught, each hauls up his end of the net until the two coracles touch and the fish are secured. Many coracles are so light and portable that they can easily be carried on the fisherman's shoulders.

Welsh coracle fishermen use a net to catch salmon on the River Teifi, 1972

Welsh coracle fishermen use a net to catch salmon on the River Teifi, 1972 Painting of North American coracles (bull boats), c.a. 1832

Painting of North American coracles (bull boats), c.a. 1832 Indian coracle on the Kaveri river

Indian coracle on the Kaveri river

In North America, American Indians and frontiersmen made coracles, called bull boats, by covering a willow frame with buffalo hide. The buffalo hair was left on the hide because it inhibited the craft from spinning, and the tails were also left intact and used to tie bull boats together.[21]

Indian coracles commonly operate on the rivers Kaveri and Tungabhadra in Southern India.[22] The smaller ones are about 6.2 feet (1.9 metres) in diameter, and are used primarily for fishing. Indian coracles have been used since prehistoric times.[14]

In Tibet, coracles, used for fishing and ferrying people, are made by stretching yak hide over juniper frames, and fastened with leather thongs. They are shaped like the Iraq coracles. Yack butter is used for waterproofing. Again, different rivers have their own designs. Sometimes two coracles are strapped together for added stability.[23][24]

Vietnamese one-man fishing coracle

Vietnamese one-man fishing coracle Off to work

Off to work Waiting for the tow at Mui Ne Beach

Waiting for the tow at Mui Ne Beach Being towed to the fishing ground.

Being towed to the fishing ground.

In Vietnam, elegant coracles constructed with bamboo, are still used from many beaches, such as at Nha Trang, Phan Thiết and Mui Ne. The coracles are towed in a line behind a motor boat, like beads on a string, to their fishing ground. There the fisherman lay fishing nets in the sea. Later, another tow returns the coracle fishermen to the beach with their catch.

Canoes

A canoe is a small narrow boat, usually pointed at both bow and stern and normally open on top, though they can be covered. A dugout is a canoe hollowed from a tree trunk. The oldest known canoe is the dugout Pesse canoe found in the Netherlands.[25] According to C14 dating analysis it was constructed somewhere between 8200 and 7600 BC.[25] This canoe is exhibited in the Drents Museum in Assen, Netherlands. Another dugout, almost as old, has been found at Noyen-sur-Seine.[26] The oldest known canoe found in Africa is the Dufuna canoe, constructed about 6000 BC. It was discovered by Fulani herdsman in Nigeria in 1987.[27]

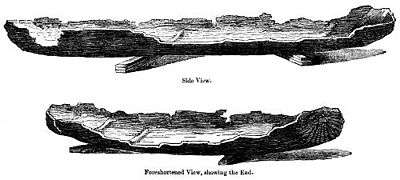

During the Iron Age residents of Great Britain used dugouts for fishing and transport. Two ancient dugouts discovered in Newport, Shropshire are on display at Harper Adams University in Newport. In 1964, a dugout was uncovered in Poole Harbour, Dorset. The Poole Logboat, dated to 300 BC, was large enough to accommodate 18 people and was constructed from a large oak tree.

Best known are the canoes of the Eastern North American Indians. These, often elegant canoes, were not dugouts, but were made of a wooden frame covered with bark of a birch tree, pitched to make it waterproof.[28]

Typically canoes are propelled with paddles, often by two people. Paddlers face in the direction of travel, either seated on supports in the hull, or kneeling directly upon the hull. Paddles can be single-bladed or double-bladed.

A pirogue is a small, flat-bottomed boat of a design associated particularly with West African fishermen[29] and the Cajuns of the Louisiana marsh. These are usually dugouts, and are light and small enough to be easily taken onto land. The design allows the pirogue to move through the very shallow water of marshes and be easily turned over to drain any water that may get into the boat. The pirogue is usually propelled by paddles with one blade. It can also be punted with a push pole in shallow water. Small sails can also be used. Outboard motors are increasingly being used in many regions.

The log canoe of Chesapeake Bay is in the modern sense not a canoe at all, though it evolved through the enlargement of dugout canoes.

Kayaks are generally differentiated from canoes by the sitting position of the paddler and the number of blades on the paddle. In a kayak the paddler faces forward, legs in front, using a double bladed paddle. In a canoe the paddler faces forward and sits or kneels in the boat, using a single bladed paddle. In some parts of the world, such as the United Kingdom, kayaks are considered a subtype of canoe. Continental European and British canoeing clubs and associations of the 19th Century used craft similar to kayaks, but referred to them as canoes.

Ancient British dugout canoe

Ancient British dugout canoe Andamanese dugout canoes, 1875

Andamanese dugout canoes, 1875 Pirogue on the Niger River

Pirogue on the Niger River Split log fishing canoe in India

Split log fishing canoe in India North American birch-bark canoe

North American birch-bark canoe Constructing a traditional dugout at Panay in the Philippines

Constructing a traditional dugout at Panay in the Philippines

Catamarans and outrigger boats

A unique innovation among the Austronesian peoples is the development of outriggers and multihulls which enabled them to be the first humans to invent sea-going vessels.[30] The earliest ships were catamarans, which developed directly from rafts. The second hull later evolved into outriggers, which are small projecting structures mounted to the sides of the boat. The earliest configuration was the single-outrigger boat which later developed into the double-outrigger boat (or trimarans).[31][32]

Outrigger boats range in size from simple dugout canoes to large plank-built ships traditionally put together with lugs and lashings (nails were not used). They used Austronesian sails characterized by a second spar at the bottom edge of the sails (unlike in western ship sails), the most notable of which is the crab claw sail (also called "Oceanic lateen") and the tanja sail (canted lug sails).[33][34]

Catamarans and single-outrigger ships are rare in Island Southeast Asia, as they have largely been replaced by double-outrigger ships. Many of the fishing boats in the Philippines and Eastern Indonesia are double-outrigger craft, consisting of a narrow main hull with two attached outriggers. They are collectively known as bangka (or banca) in the Philippines, and jukung in Indonesia. They were traditionally fitted with crab claw sails or lug sails, but in modern times are commonly fitted with petrol engines instead.[35] However, larger outrigger crafts also exist, like the paraw, lanong, basnigan, and the karakoa of the Philippines, as well as the kora-kora of the Maluku Islands. These were usually served as motherships for deepwater fishing or as merchant or cargo ships.

Catamarans and single-outrigger ships dominate the ship configurations in Oceania, however. Oceanian catamarans typically consists of two canoes, or vakas, joined by a frame, formed of akas.[33]

Catamarans and outrigger ships have also been introduced by Austronesians to other cultures through early trading contacts. Notably, it was introduced early (around 1500 BC) to Sri Lanka and southern India. It was also introduced to eastern Africa when Austronesians from Southeast Asia colonized Madagascar and the Comoros.[31]

Ropes and lines

The availability of reliable and durable ropes and lines has had many consequences for the development and utility of traditional fishing boats. They can be used to lash planks and frames together, as stay lines for masts, as anchor lines to secure the boat, and as fishing lines for making fishing nets.

Ropes and lines are made of fibre lengths, twisted or braided together to provide tensile strength. They are used for pulling, but not for pushing.

Fossilised fragments of "probably two-ply laid rope of about 7 mm diameter" have been found in one of the caves at Lascaux, dated about 15,000 BC.[36] Egyptian rope dates back to 4000 to 3500 BC and was generally made of water reed fibers. Other rope in antiquity was made from the fibers of date palms, flax, grass, papyrus, leather, or animal hair. Rope made of hemp fibres was in use in China from about 2800 BC.

Propulsion

Before engines became available, boats could be propelled manually or by the wind. Boats could be propelled by the wind by attaching sails to masts set upright in the boat. Manual propulsion could be done in shallow water by punting with a push pole, and in deeper water by paddling with a paddle or rowing with oars. The difference between paddling and rowing is that when rowing the oars have a mechanical connection with the boat, while when paddling the paddles are hand-held with no mechanical connection. Canoes were traditionally paddled, with the paddler facing the bow of the boat. Small boats that use oars are called rowboats, and the rower typically faces the stern.

Around 4000 B.C., Egyptians were building long narrow boats powered by many oarsmen. Over the next 1,000 years, they made a series of remarkable advances in boat design. They developed cotton-made sails to help their boats go faster with less work. Then they built boats large enough to cross the oceans. These boats had sails and oarsmen, and were used for war and trade. Some ancient vessels were propelled by either oars or sail, depending on the speed and direction of the wind (see trireme and bireme). The Chinese were using sails around 3000 BC, of a type that can still be seen on traditional fishing boats sailing off the coast of Vietnam in Ha Long Bay.

A jangada is an elegant planked fishing boat used in northern Brazil. It has been claimed the jangada dates back to ancient Greek time.[37] It uses a triangular (lateen) sail, which allows it to sail against the wind.

A felucca is a traditional wood-planked sailing boat used in protected waters of the Red Sea and eastern Mediterranean including Malta, and particularly along the Nile in Egypt. Its rig consists of one or two lateen sails.

Traditional fishing lakana with distinctive Austronesian Crab-claw sail from Madagascar

Traditional fishing lakana with distinctive Austronesian Crab-claw sail from Madagascar

Small junk sailing in Halong Bay, Vietnam

Small junk sailing in Halong Bay, Vietnam

Planking

Building boats from planks meant boats could be more precisely constructed along the line of large canoes than hollowing tree trunks allowed. It is possible that planked canoes were developed as early as 8,500 years ago in Southern California.[38]

By 3000 BC, the Egyptians knew how to assemble planks of wood into a ship hull.[39] They used woven straps to lash planks together,[39] and reeds or grass stuffed between the planks to seal the seams.[39] An example of their skill is the Khufu ship, a vessel 143 feet (44 m) in length entombed at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza around 2500 BC and found intact in 1954.

Planked fishing boat in Kasenyi, Uganda

Planked fishing boat in Kasenyi, Uganda- Planked fishing boat on the beach of Narikel Zinzira, Bangladesh

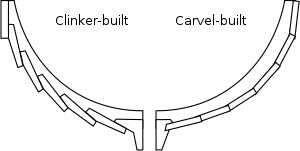

A further development was the use of timber frames, to which the planks could be lashed, stitched or nailed. With the use of frames, it is possible to develop carvel-style and clinker-style planking (in the USA the term lapstrake is used instead of clinker). Scandinavians were using clinker construction by at least 350 BC.[40][40]

Carvel construction dates back even earlier. A luzzu is a double-ended carvel-built fishing boat from the Maltese islands. Traditionally, they are brightly painted in shades of yellow, red, green and blue, and the bow is normally pointed with a pair of eyes. These eyes may be the modern survival of an ancient Phoenician custom (also practiced by the ancient Greeks); they are sometimes (and probably inaccurately) referred to as the Eye of Horus or of Osiris. The luzzu has survived because it tends to be a sturdy and stable boat even in bad weather. Originally, the luzzu was equipped with sails although nowadays almost all are motorised, with onboard diesel engines being the most common.

Building a carvel boat at Quee Ngon, Vietnam

Building a carvel boat at Quee Ngon, Vietnam Clinker built fishing boats at Jantar Beach

Clinker built fishing boats at Jantar Beach Decked fishing boat at Koh Rung Samleom, Cambodia

Decked fishing boat at Koh Rung Samleom, Cambodia

European boats

Boats in South East Asia and Polynesia centred on canoes, outriggers and multihull boats. By contrast, boats in Europe centred on framed and keeled monohulls.

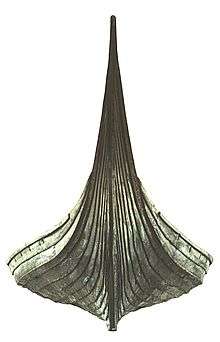

The Scandinavians were building innovative boats millennia ago, as shown by the many petroglyph images of Nordic Bronze Age boats. The oldest archaeological find of a wooden Nordic boat is the Hjortspring boat, built about 350 BC. This is the oldest known boat to use clinker planking, where the planks overlap one another. It was designed as a large canoe, 19 m long and crewed by 22–23 men using paddles. Scandinavians continued to develop better boats, incorporating iron and other metal into the design, adding keels, and developing oars for propulsion.[40][41] Another Nordic shipfind is the Nydam boat, found preserved in the Nydam Mose bog in Sundeved, Denmark. It has been dendro dated to 310-320 AD. Built of oak, it is also clinker-built, is 23 metres long and was rowed by thirty men.[42]

By 1000 A.D. the Norsemen were pre-eminent on the oceans. They were skilled seamen and boat builders, with clinker-built boat designs that varied according to the type of boat. Trading boats, such as the knarrs, were wide to allow large cargo storage. Raiding boats, such as the longship, were long and narrow and very fast. The vessels they used for fishing were scaled down versions of their cargo boats. The Scandinavian innovations influenced fishing boat design long after the Viking period came to an end. For example, yoles from the Orkney Island of Stroma were built in the same way as the Norse boats, as were the Shetland yoals and the sgoths of the Outer Hebrides..

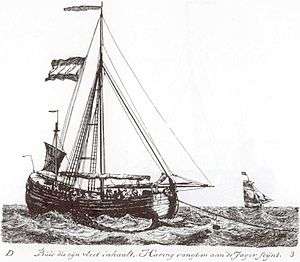

In the 15th century, the Dutch developed a type of sea-going herring drifter that became a blueprint for subsequent European fishing boats. This was the herring buss, used by Dutch herring fishermen until the early 19th centuries. The ship type buss has a long history. It was known around 1000 AD in Scandinavia as a bǘza, a robust variant of the Viking longship. The first herring buss was probably built in Hoorn around 1415. The last one was built in Vlaardingen in 1841. The ship was about 20 metres long and displaced between 60 and 100 tons. It was a massive round-bilged keel ship with a bluff bow and stern, the latter relatively high, and with a gallery. The busses used long drifting gill nets to catch the herring. The nets would be retrieved at night and the crews of eighteen to thirty men[43] would set to gibbing, salting and barrelling the catch on the broad deck. The ships sailed in fleets of 400 to 500 ships[43] to the Dogger Bank fishing grounds and the Shetland isles. They were usually escorted by naval vessels, because the English considered they were "poaching". The fleet would stay at sea for weeks at a time. The catch would sometimes be transferred to special ships (called ventjagers), and taken home while the fleet would still be at sea (the picture shows a ventjager in the distance).[43]

.jpg)

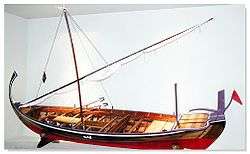

During the 17th century, the British developed the dogger, an early type of sailing trawler or longliner, which commonly operated in the North Sea. The dogger takes its name from the Dutch word dogger, meaning a fishing vessel which tows a trawl. Dutch trawling boats were common in the North Sea, and the word dogger was given to the area where they often fished, which became known as the Dogger Bank.[44] Doggers were slow but sturdy, capable of fishing in the rough conditions of the North Sea.[45] Like the herring buss, they were wide-beamed and bluff-bowed, but considerably smaller, about 15 metres long, a maximum beam of 4.5 m, a draught of 1.5 m, and displacing about 13 tonnes. They could carry a tonne of bait, three tonnes of salt, half a tonne each of food and firewood for the crew, and return with six tonnes of fish.[45] Decked areas forward and aft probably provided accommodation, storage and a cooking area. An anchor would have allowed extended periods fishing in the same spot, in waters up to 18 m deep. The dogger would also have carried a small open boat for maintaining lines and rowing ashore.[45]

During the same period, small boats were also undergoing development. The French bateau type boat was a small flat bottom boat with straight sides used as early as 1671 on the Saint Lawrence River.[46] The common coastal boat of the time was the wherry and the merging of the wherry design with the simplified flat bottom of the bateau resulted in the birth of the dory. Antecdotal evidence exists of much older precursors throughout Europe. England, France, Italy, and Belgium have small boats from medieval periods that could reasonably be construed as predecessors of the dory.[47] In Ireland, the Gandelow was used to fish for salmon in the Shannon estuary from the 1600s onwards.

Dories are small, shallow-draft boats, usually about five to seven metres (15 to 22 feet) long. They are lightweight versatile boats with high sides, a flat bottom and sharp bows, and are easy to build because of their simple lines. The dory first appeared in New England fishing towns sometime after the early 18th century.[48] The Banks dories appeared in the 1830s. They were designed to be carried on mother ships and used for fishing cod at the Grand Banks.[48] Adapted almost directly from the low freeboard, French river bateaus, with their straight sides and removable thwarts, bank dories could be nested inside each other and stored on the decks of fishing schooners, such as the Gazela Primeiro, for their trip to the Grand Banks fishing grounds.

In the 19th century, a more effective design for sailing trawlers was developed at the English fishing port, Brixham. These elegant wooden sailing boats spread across the world, influencing fishing fleets everywhere. Their distinctive sails inspired the song Red Sails in the Sunset, written aboard a Brixham sailing trawler called the Torbay Lass. In the 1890s there were about 300 trawling vessels there, each usually owned by the skipper of the boat. Several of these old sailing trawlers have been preserved.[49][50]

Throughout history, local conditions have led to the development of a wide range of types of fishing boats. The Lancashire nobby was used down the north west coast of England as a shrimp trawler from 1840 until World War II. The bawley and the smack were used in the Thames Estuary and off East Anglia, while trawlers and drifters were used on the east coast. Herring fishing started in the Moray Firth in 1819. The Manx nobby was used as a herring drifter around the Isle of Man, and fifies were used as herring drifters along the east coast of Scotland from the 1850s until well into the 20th century.

Notes

- FAO (2007) The status of the fishing fleet State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. ISBN 978-92-5-105568-7

- McGrail 2004, page 431

- "Oldest Boat Unearthed". China.org.cn. Archived from the original on 2009-01-02. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- Lawler, Andrew (June 7, 2002). "Report of Oldest Boat Hints at Early Trade Routes". Science. 296 (5574): 1791–1792. doi:10.1126/science.296.5574.1791. PMID 12052936.

- FAO 2007

- FAO: Country Profile: Indonesia

- Experiences With Fish Aggregating Devices In Sri Lanka FAO

- McGrail S (1985) Towards a classification of Water transport World Archeology, 16 (3).

- Encyclopædia Britannica Online: Lake Titicaca. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- "Puno" (PDF). Mincetur.

- Heiser C. B. (1974) "Totoras, Taxonomy, and Thor" Plant ScienceBulletin, 20 (2).

- de Graafa M, van Zwietenb PAM, Machielsb MAM, Lemmac E, Wudnehd T, Dejene E and Sibbing FA () "Vulnerability to a small-scale commercial fishery of Lake Tana's (Ethiopia) endemic Labeobarbus compared with African catfish and Nile tilapia: An example of recruitment-overfishing?" Fisheries Research, 82 (1-3) 304-318.

- Sordinas A (1970) "Stone implements from northwestern Corfu", Anthropological Research Center, University of Memphis.

- Encyclopædia Britannica - Coracle

- The Official website of The Coracle Society

- Hornell, James (1946) Water transport : origins & early evolution, Page 101–108, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-7153-4860-4.

- Coracle man won’t let this one get away TimesOnline, 23 February 2008.

- A good little vessel The New Yorker, 2 June 1986, p. 38.

- The Welsh Coracle: The Tradition of Coracle Fishing in Wales Archived 2009-10-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Map of Welsh Rivers and Coracle Types

- Bull Boats: Crossing Rivers, Indian Style From Discovering Lewis & Clark.

- Coracles of South India

- Hornell, James (1946) Water transport : origins & early evolution, Page 99–100, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-7153-4860-4.

- Coracles on Tsangpo River at Nyapso La

- "The Mysterious Bog People - Background to the exhibition". Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation. 2001-07-05. Archived from the original on March 9, 2007. Retrieved 2009-06-01.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- McGrail 2004, page 174

- Garba, Abubakar (1996) "The architecture and chemistry of a dug-out: the Dufuna Canoe in ethno-archaeological perspective" Berichte des Sonderforschungsbereichs, 268 (8): 193–200.

- Hodgins BW, Jennings J and Small D (1999) The Canoe in Canadian Cultures Natural Heritage Books. ISBN 1-896219-48-9

- Setting sail. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- Meacham, William (1984–1985). "On the improbability of Austronesian origins in South China" (PDF). Asian Perspective. 26: 89–106.

- Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". In Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.). Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts. One World Archaeology. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN 0415100542.

- Doran, Edwin B. (1981). Wangka: Austronesian Canoe Origins. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9780890961070.

- Beheim, B. A.; Bell, A. V. (23 February 2011). "Inheritance, ecology and the evolution of the canoes of east Oceania". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1721): 3089–3095. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0060. PMC 3158936. PMID 21345865.

- Hornell, James (1932). "Was the Double-Outrigger Known in Polynesia and Micronesia? A Critical Study". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 41 (2 (162)): 131–143.

- FAO: Country Profile: Philippines

- J.C. Turner and P. van de Griend (ed.), The History and Science of Knots (Singapore: World Scientific, 1996), 14.

- Lima, Paul The raft men of Brazil Archived 2008-11-21 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 25 April 2008.

- Fagan, B (2004) "The House of the Sea" An Essay on the Antiquity of Planked Canoes in Southern California" Society for American Archaeology

- Ward, Cheryl. "World's Oldest Planked Boats," in Archaeology (Volume 54, Number 3, May/June 2001). Archaeological Institute of America, .

- Sawyer, Peter Hayes (2001) The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings Page 183. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285434-6

- Nationalencyklopedin

- The Nydam Societys homepage Archived 2007-07-15 at the Wayback Machine

- De Vries & Woude (1977), pages 244–245

- Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea, p. 256

- Fagan 2008

- Gardner 1987, page 18

- Gardner 1987, page 15

- Chapelle, page 85

- History of a Brixham trawler Archived 2010-12-02 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- Pilgrim's restoration under full sail BBC. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

References

- Chapelle, Howard L. (1951) American Small Sailing Craft WW Norton Company, New York, ISBN 0-393-03143-8

- Fagan, Brian (2008) The Great Warming. Chapter 10: Bucking the trades Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-392-9

- FAO: CWP Handbook of Fishery Statistical Standards : Section L: Fishery Fleet

- FAO (2007) The status of the fishing fleet State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. ISBN 978-92-5-105568-7

- Forman, Shepard (1970) The raft fishermen: Tradition & change in the Brazilian peasant economy, Indiana University Press for International Affairs Center. ISBN 0-253-39201-2

- Gardner, John (1987) The Dory Book. Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic Connecticut. ISBN 0-913372-44-7

- Johnstone, Paul (1889) The Sea-Craft of Prehistory, Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-02635-2

- McGrail, Sean (2004). Boats of the World: From the Stone Age to Medieval Times. USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-927186-0.

- Vries, J. de, and Woude, A. van der (1997), The First Modern Economy. Success, Failure, and Perseverance of the Dutch Economy, 1500-1815, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-57825-7

Reading

- Adney ET, Chappelle HI and McPhee J (2007) Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 1-60239-071-1

- Gerr, Dave (1995) The Nature of Boats: Insights and Esoterica for the Nautically Obsessed McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-024233-3

- Smylie, Michael (1999) Traditional Fishing Boats of Britain & Ireland: Design, History and Evolution. Adlard Coles Nautical. ISBN 978-1-84037-035-5

- Smylie, Mike (2013) Traditional Fishing Boats of Europe Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445614342.

- Traung, Jan-Olaf (1960) Fishing Boats of the World 2 Fishing News (Books) Ltd. Download PDF (99MB)

- Traung, Jan-Olaf (1967) Fishing Boats of the World 3 Kiefer Press. ISBN 978-1-4437-6711-8. Download PDF (56MB)

- Vigor, John (2004) The Practical Encyclopedia of Boating: An A-Z Compendium of Seamanship, Boat Maintenance, Navigation, and Nautical Wisdom McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-137885-7

- Woodman, Richard (1998) The History of the Ship: The Comprehensive Story of Seafaring from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-681-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fishing boats. |

- The Uros People at GlobalAmity.net

- Video tour of Uros floating fishing villages

- Uros Indian Culture - Home

- Floating islands on Google Maps

- Trujillo, The Golden Steeds of Huanchaco

- Indigenous boats: Small craft outside the Western tradition

- A history of shipbuilding in Newfoundland

- Jangadeiros, the fishermen in the northeastern Brazil

- Indigenous sails

.jpg)