Tigrayans

The Tigrayans are an ethnolinguistic group indigenous to the highlands of Eritrea and the Tigray Region of Ethiopia.[13][14][15] They speak the Tigrinya language, a direct descendant of the Ge’ez language that was spoken in late antiquity.[16][17]

Tigray girls | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 4.80 million[1] | |

| 3,255,405 | |

| c. 33,000[2][Note 1] | |

| c. 20,000[3] | |

| c. 13,500[4] | |

| 32,400[5] | |

| 10,220[6] | |

| c. 7,500[7] | |

| c. 4,600[8] | |

| c. 3,000[9] | |

| 2,794[10] | |

| 1,235[11] | |

| Languages | |

| Tigrinya | |

| Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

In Eritrea they make up about 55% of the population, i.e. above three million people (and additionally half a million in the diaspora), and in Ethiopia there are about 4.5 million Tigrayans, according to the 2007 census, most of them in the Tigray Region.[18][19][20] Over 90% of Tigrayans are Christians. The great majority are Ethiopian Orthodox Christian and Eritrean Orthodox Christian, but there are minorities of Muslims, Beta Israel, and since the 19th century, Protestants in Eritrea and Catholics mainly in Akele Guzay and Agame. Most Tigrayans are traditionally agriculturalists, practicing plough agriculture (cultivating teff, sorghum, millet, wheat, maize, etc.) and also keeping cattle, sheep and goats (but usually without stock-breeding), and in many areas bees Some Tigrayan groups have a strong local identity and used to have their own traditional, quite autonomous self-organization, sometimes dominated by egalitarian assemblies of elders, sometimes by leading families or local feudal dynasties.[21] In some areas the meritorious complex played a considerable role in achieving a social status, which led to the creation of local honorary titles and social institutions, and, historically, to an active involvement in the warfare of Christian Ethiopia; through this, even the sons of simple peasants could rise considerably in the state of hierarchy.

The daily life of Tigrayans are highly influenced by religious concepts. For example, the Christian Orthodox fasting periods are strictly observed, especially in Tigray; but also traditional local beliefs such as in spirits, are widespread. In Tigray the language of the church remains exclusively Ge’ez; in Eritrea also Tigrinya is used in the Orthodox Church context, but rather as an exception (different from Protestant churches, well-enrooted in Hamasen and urban Eritrea). Tigrayan society is marked by a strong ideal of communitarianism and, especially in the rural sphere, by egalitarian principles. This does not exclude an important role of gerontocratic rules and in some regions such as the wider Adwa area, formerly the prevalence of feudal lords, who, however, still had to respect the local land rights.[13]

Etymology

.jpg)

The first possible mention of the group dates from around 525 AD in Adulis, in which period manuscripts preserving the inscriptions of Cosmas Indicopleustes contain notes on his writings including the mention of a tribe called Tigretes.[22]

History

The majority of Tigrayans trace their origin to early Semitic-speaking peoples whose presence in the region dates back to at least 2000 BC, based on linguistic evidence (and known from the 9th century BC from inscriptions).[23] According to Ethiopian traditions, the Tigrayan nobility; i.e. that of the former Kingdom of Tigray, trace their ancestry to the legendary king Menelik I, the child born of the queen of Sheba and King Solomon as do the priests of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (Ge'ez ካህን kāhin). Menelik I would become the first king of the Solomonic dynasty of rulers of Ethiopia that ended only with the deposing of Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974.

The first possible mention of the group dates from around the 8th to 10th centuries, in which period manuscripts preserving the inscriptions of Cosmas Indicopleustes (fl. 6th century) contain notes on his writings including the mention of a tribe called Tigretes.[22] A Portuguese Map in the 1660 shows Medri Bahri consisting of the three highland provinces of Eritrea and distinct from Ethiopia.[24] The Bahre-Nagassi ("Kings of the Sea") alternately fought with or against the Abyssinians and the neighbouring Muslim Adal Sultanate depending on the geopolitical circumstances. Medri Bahri was thus part of the Christian resistance against Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi of Adal's forces, but later joined the Adalite states and the Ottoman Empire front against Abyssinia in 1572. That 16th century also marked the arrival of the Ottomans, who began making inroads in the Red Sea area.[25] Bruce noted "They next passed the Mareb, which is the boundary between Tigre and the Baharnagash".[26] James Bruce in his book published in 1805 located Tigré (a region based arbitrarily by James Bruce on the Language of Tigrinya) between Red Sea and the Tekezé River and stated many large governments, such as Enderta and Antalow, and the great part of Baharhagash were part of Tigré region based on the language of Tigrinya.[27][28][29]

By the beginning of the 19th century Henry Salt (Egyptologist), who travelled in the interior of Abyssinia, divided the "Abyssinia" region, like James Bruce into three distinct and independent states.[30][31] These three great divisions(based arbitrarily on Language) are Tigré, Amhara, and the province of Shoa.[30] Henry considers Tigré as the more powerful state of the three; a circumstance arising from the natural strength of the country, the warlike disposition of its inhabitants, and its vicinity to the sea coast; an advantage that has secured to it the monopoly of all the musquets imported into the country.[32] He divided the Tigré kingdom into several provinces as the centre where it was considered the seat of the state being referred as Tigré proper. Provinces of this kingdom includes Enderta, Agame, Wojjerat, Temben, Shiré and Baharanegash.[32] Hamasien, a district of Baharanegash, is the furthest north and narrowest part of Tigré, and Henry places Bejas or Bojas as the people who live north of Tigré state.[33][34] By the time Henry made his travel to Abyssinia the seat of the empire, Gondar, was ruled by Gugsa of Yejju, an Wollo commander who ruled from 1798 up to 1825 as enderase to the powerless emperors with Solomonic dynasty.[35][36]

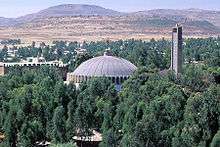

Demographics

Tigrayans constitute approximately 6.1% of the population of Ethiopia and are largely small holding farmers inhabiting small communal villages. They are also mainly Christian and members of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (approximately 96%), with a small minority of Muslims, Catholics and Protestants. The predominantly Tigrayan populated urban centers in Ethiopia are found within the Tigray Region in towns including Mekelle, Adwa, Axum, Adigrat, and Shire and in Eritrea are Asmara and Keren. Populations of Tigrayans are also found in other large Ethiopian cities such as the capital Addis Ababa and Gondar as well as abroad in the United States.

The Tigrayans are, despite a general impression of homogeneity, composed of numerous subgroups with their own socio-cultural traditions. Among these there are the Agame of eastern Tigray, mentioned in the Monumentum Adulitanum in the 3rd century; the autonomous Senadegle and Meretta of Akkele Guzay in Eritrea; the Hamasenay, agriculturalists in Hamasen and cattle herders in Humera; the egalitarian Wajjarat of south-eastern Tigray. Many others, sometimes numbering only a few thousands and scattered over several districts, could be listed. Usually they define themselves through common descent, but in some cases also as a political confederacy uniting different groups (such as the Shewatte Anseba on the north-western borders of the Eritrean highlands). Assimilation processes, which still continue, have led to the inclusion of other ethnic (sub-)groups. For example, Agaw settlers in Seraye, the Adkeme Malga became Tigrayans several centuries ago; some Bilin villages near Keren now also belong to the Tigrayans.[13]

The subgroups are composed of descent groups and lineages. Often these are called "Deqqi-...", sometimes also "Ad...", after a common ancestor, such as the Deqqi Tesfa of the western lowlands of Seraye or the Ad Deggiyat, a name for the Seazzega dynasty of the Mereb Melash. In addition, there are ancient, more vague group-designations above the level of subgroups, used by elders as identity-markers: Agaziyan (descendants of the Agazi) for the inhabitants of Agame and Akkele Guzay, and Sabawiyan for the people of Aksum and Yeha.[13]

The decline of the Tigrayan population in Ethiopia during Haile Selassie's reign – in particular in districts of the former Tigray province, which are given to the present-day Amhara Region, like Addi Arkay (woreda), Kobo (woreda) & Sanja (woreda) – is likely to have been as a result of Haile Selassie's suppression and systematic persecution against non-Amhara ethnic peoples of Ethiopia (in particular, his immense systematic persecution of Tigrayans). For example, on the 1958 famine of Tigray, Haile Selassie refused to send any significant basic emergency food aid to Tigray province despite having the resources to; as a consequence, over 100,000 people died of the famine.[37][38][39]

Later on, the Mengistu Haile Mariam-led brutal military dictatorship (Derg) also used the 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia as government policy (by restricting food supplies) for counter-insurgency strategy (against Tigray People's Liberation Front guerrilla-soldiers), and for "social transformation" in non-insurgent areas (against people of Tigray province, Welo province and such).[40][41][42] Due to organized government policies that deliberately multiplied the effects of the famine, around 1.2 million people died in Ethiopia from this famine where majority of the death tolls were from Tigray province (and other parts of northern Ethiopia).[43][44][45]

Religion

.jpg)

Tigrayans are mostly Christians, with an Oriental Orthodox majority and a Catholic minority. Tigrayan Muslims are virtually all Sunni, though a minority of Ahbash followers also exists. There are also Tigrayan communities consisting of Jews, known as the Beta Israel. Majority of these peoples have now migrated to Israel.

History

Before the coming of Christianity, most Tigrayans followed a pagan religion with a number of deities, including the sun god Utu, and the moon god Almaqah. Some tribes however practiced Judaism. The most prominent polytheistic kingdoms were the Kingdoms of D’mt and early Aksum.

Christianity

Christianity has been the predominant religion of Tigrayans since antiquity, when the Aksumite king Ezana converted to Christianity in the late 3rd century and declared it the state religion. They have played a fundamental role in the development of the faith. With the expansion of Islam, the Tigrayans were pushed out from the coast and forced to remain in the highlands to avoid Islamization. Today, Orthodox Tewahedo dominates in most areas, overwhelmingly so in rural areas.

Islam

Islam was introduced to the area early on, when the Prophet Muhammad's companions found refuge in the Aksumite Kingdom. While some of Muhammad's companions returned to the Arabian peninsula, some stayed back as refugees and converted a number of people to Islam. These new converts were called Jeberti meaning “the elect of god”. Today, the Muslim community, is concentrated mainly in urban areas. Many Jeberti in Eritrea claim that they are a separate ethnic group from other Tigrayans in the area and consider their native languages to be both Arabic and Tigrinya, and are thus treated as a separate ethno-religious community.[46]

Culture

Tigrayans are sometimes described as “individualistic”, due to elements of competition, jealousy and local conflicts.[47] This, however, rather reflects a strong tendency to defend one's own community and local rights against—then widespread—interferences, be it from more powerful individuals or the state. Tigrayan communities are marked by numerous social institutions with a strong networking of character, where relations are based on mutual rights and bonds. Economic and other support is mediated by these institutions. In the urban context, the modern local government have taken over the functions of traditional associations. In most rural areas, however, traditional social organizations are fully in function. All members of such an extended family are linked by strong mutual obligations.[48] Villages are usually perceived as genealogical communities, consisting of several lineages.[13]

A remarkable heritage of Tigrayans are their customary laws. In Eritrea, several Tigrayan groups have elaborated them as written law books, which are still valid locally (subsidiary to state law). In Tigray, customary law is also still partially practiced to some degree even in political self-organization and penal cases. It is also of great importance for conflict resolution.[21]

Language

Tigrayans speak Tigrinya language as a mother tongue. It belongs to the Ethiopian Semitic subgroup of the Afroasiatic family.[49]

Tigrinya is closely related to Amharic and Tigre, another Afroasiatic language spoken by the Tigre as well as many Beja. Tigrinya and Tigre although close are not mutually intelligible. Tigrinya has traditionally been written using the same Ge'ez alphabet (fidel) as Amharic, whereas Tigre has been transcribed mainly using the Arabic script. Attempts by the Eritrean government to have Tigre written using the Ge'ez script has met with some resistance from the predominantly Muslim Tigre people who associate Ge'ez with the Orthodox Tewahedo Church and would prefer the Arabic or the more neutral Latin alphabet. It has also met with the linguistic difficulty of the Ge'ez script being a syllabic system which does not distinguish long vowels from short ones. While this works well for writing Tigrinya or Amharic, which do not rely on vowel length in words, it does complicate writing Tigre, where vowel length sometimes distinguishes one word and its meaning from another. The Ge'ez script evolved from the Epigraphic South Arabian script, whose first inscriptions are from the 8th century BC in Eritrea, Ethiopia and Yemen.

In Ethiopia, Tigrinya is the third most spoken language. The Tigrayans constitute the fourth largest ethnic group in the country after the Oromo, Amhara and Somali, who also speak Afro-Asiatic languages.[50] In Eritrea, Tigrinya is by far the most spoken language, where it is used by around 55% of the population. Tigre is used by around 30% of residents.

Tigrinya dialects differ phonetically, lexically, and grammatically.[51] No dialect appears to be accepted as a standard.

Cuisine

Tigrayan food characteristically consists of vegetable and often very spicy meat dishes, usually in the form of tsebhi (Tigrinya: ፀብሒ), a thick stew, served atop injera, a large sourdough flatbread.[22] As the vast majority of Tigrayans belong to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church (and the minority Muslims), pork is not consumed because of religious beliefs. Meat and dairy products are not consumed on Wednesdays and Fridays, and also during the 7 compulsory fasts. Because of this reason, many vegan meals are present. Eating around a shared food basket, mäsob (Tigrinya: መሶብ) is a custom in the Tigray region and is usually done so with families and guests. The food is eaten using no cutlery, using only the fingers (of the right hand) and sourdough flatbread to grab the contents on the bread.[52][53]

Regional dishes

T'ihlo (Tigrinya: ጥሕሎ, ṭïḥlo) is a dish originating from the historical Agame and Akkele Guzai provinces. The dish is unique to these parts of both countries, but is now slowly spreading throughout the entire region. T'ihlo is made using moistened roasted barley flour that is kneaded to a certain consistency. The dough is then broken into small ball shapes and is laid out around a bowl of spicy meat stew. A two-pronged wooden fork is used to spear the ball and dip it into the stew. The dish is usually served with mes, a type of honey wine.[54]

Notable People

Ras Alula (Abba Nega) of Tigray, commander of the Battle of Adwa

Ras Alula (Abba Nega) of Tigray, commander of the Battle of Adwa_(cropped).jpg) Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the first ever African Director-General of the World Health Organization

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the first ever African Director-General of the World Health Organization Eritrean Tigrayan artist Helen

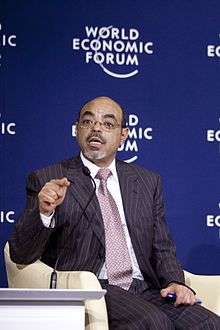

Eritrean Tigrayan artist Helen Tigrayan politician Meles Zenawi, the former Prime Minister of Ethiopia.

Tigrayan politician Meles Zenawi, the former Prime Minister of Ethiopia. Debretsion Gebremichael, President of Tigray Region (Acting).

Debretsion Gebremichael, President of Tigray Region (Acting).

- Meles Zenawi – Former Prime Minister of Ethiopia

- Yohannes IV - Emperor of Ethiopia born in Tembien, Ethiopian Empire

- Isaias Afwerki - President of Eritrea [55]

- Debretsion Gebremichael – Vice-President of Tigray (Acting as president).

- Gebrehiwot Baykedagn – was an Ethiopian doctor, economist, and intellectual.

- Zera Yacob – Ethiopian philosopher

- Aba Estephanos – Ethiopian religious revolutionist born to the east of Axum, founder of the Däqiqä Əsṭifanos monastic order

- Sebhat Ephrem – Former Eritrean Minister of Defence

- Saint Yared – Ethiopian saints create the sacred music tradition of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

- Sebhat Gebre-Egziabher – Ethiopian writer

- Tewolde Berhan Gebre Egziabher – world-renowned environmental scientist

- Kinfe Abraham – Tigrayan-Jewish, former president of Horn of Africa Democracy and Development

- Gebregziabher Gebremariam – runner who won 5 times in the World Cross Country Championships

- Werknesh Kidane – runner who won a gold medal in the 2003 World Cross Country Championships

- Abeba Aregawi – runner and gold medalist of world, world indoor and European indoor

- Tsgabu Gebremaryam Grmay – road cyclist one time African time trial champion

- Siye Abraha – leading the UN Development Programme's security sector reform in Liberia

- Abune Mathias – "His Holiness Abune Mathias I, Sixth Patriarch and Catholicos of Ethiopia, Archbishop of Axum and Ichege of the See of Saint Taklehaimanot.

- Tedros Adhanom – The Director General of World Health Organization [56]

- Arkebe Oqubay - is a senior Ethiopian politician, a Minister and Special Advisor to the former Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Hailemariam Desalegn.

- Gebrehiwot Baykedagn – was one of the pioneer Ethiopian doctor, economist, and intellectual.

- Yohannes IV – Emperor of Ethiopia

- Atse Baeda Maryam – Emperor of Ethiopia son of Ras Mikael Sehul[57]

- Mikael Sehul – Ras of Ethiopia

- Haile Selassie Gugsa – Dejazmatch from Ethiopia

- Wolde Selassie- Ras of Ethiopia

- Ras Alula (Abba Nega) – 19th Century Ras of Ethiopia

- Sara Nuru – (mother from Axum) winner of the fourth cycle of Germany's Next Top Model

- Ras Mengesha Yohannes – Ras of Tigray.

- Hayelom Araya – Ethiopian General of the army[58]

- Miruts Yifter – athlete who won two gold medals in the 1980 Moscow Olympics

- Abune Paulos – Former Patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.

- Aman Andom - first post-imperial President of Ethiopia

- Yemane Ghebremichael (Baria) - Eritrean revolutionary national singer[59]

- Bahta Hagos - 19th century Dejazmach of Akkele Guzay[60]

- Abraham Afewerki - was an Eritrean singer, songwriter and music producer. Noted for his unique Tigrinya-based compositions and lyrics.

- Helen Meles - Eritrean popular singer[61]

- Woldemichael Solomon - 19th century governor of Medri Bahri and Hamasien[62]

- Kiros Alemayehu - Kiros was a prolific songwriter and singer. He popularized Tigrigna songs through his albums to the non-Tigrinya speaking Ethiopians.

- Eyasu Berhe - was an Ethiopian singer, writer, producer and poet, as well as a member of the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF).

Notes

- Roughly half of the Eritrean diaspora

References

- http http://www.csa.gov.et/ehioinfo-internal

- "Anzahl der Ausländer in Deutschland nach Herkunftsland". Das Statistik Portal.

- "Foreign-born persons by country of birth, age, sex and year". Statistics Sweden.

- "Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents". Statistics Norway.

- "United Kingdom". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics (2013-02-05). "2011 Census of Canada: Topic-based tabulations – Detailed Mother Tongue (232), Knowledge of Official Languages (5), Age Groups (17A) and Sex (3) for the Population Excluding Institutional Residents of Canada and Forward Sortation Areas, 2011 Census". 12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- "Population by migration background". Statistics Netherlands.

- "Istat.it". Statistics Italy.

- "Population by country of origin". Statistics Denmark.

- "The People of Australia Statistics from the 2011 Census, Cat. no. 2901.0, ABS" (PDF). Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-04-17. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- "Väestö 31.12. Muuttujina Maakunta, Kieli, Ikä, Sukupuoli, Vuosi ja Tiedot".

- Pagani, Luca; Kivisild, Toomas (July 2012). "Ethiopian Genetic Diversity Reveals Linguistic Stratification and Complex Influences on the Ethiopian Gene Pool". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 91 (1): 83–96. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.05.015. PMC 3397267. PMID 22726845.

- Smidt, Wolbert (2007). "Tigrayans". In Uhlig, Siegbert (ed.). Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Shinn, David; Ofcansky, Thomas (2004). Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. pp. 378–380. ISBN 978-0-8108-4910-5.

- Ullendorff, Edward (1973). The Ethiopians. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 31, 35–37.

- Levine, Donald (1965). Wax & Gold. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 1–2.

- Lipsky, George (1962). Ethiopia: its people, its society, its culture. New Haven: Hraf Press. p. 34.

- "Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census". Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency. December 2008. Archived from the original

|archive-url=requires|url=(help) on 25 March 2009. Missing or empty|url=(help) - "Ethiopia: A Model Nation of Minorities" (PDF). Bxabeg.people.wm.edu. Retrieved 22 March 2006.

- "Africa :: Eritrea — the World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency".

- Saleh, Abdulkader; Hirt, Nicole (2008). "Traditional Civil Society in the Horn of Africa and its Contribution to Conflict Prevention: The case of Eritrea". Horn of Africa Bulletin. 11: 1–4.

- Munro-Hay, Aksum, pp. 187

- Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum: A Civilization of Late Antiquity (Edinburgh: University Press, 1991), pp. 57

- Pateman, Roy (26 August 1998). Eritrea: Even the Stones are Burning. The Red Sea Press. ISBN 9781569020579. Retrieved 26 August 2017 – via Google Books.

- Okbazghi Yohannes (1991). A Pawn in World Politics: Eritrea. University of Florida Press. ISBN 9780813010441.

- Bruce, James (1 November 2017). "Travels through part of Africa, Syria, Egypt ..." – via Google Books.

- James Bruce Travels through part of Africa, Syria, Egypt .... Published in 1805 pp. 229 & 230 Google Books

- James Bruce Travels through part of Africa, Syria, Egypt .... Published in 1805 pp. 171 Google Books

- James Bruce Travels through part of Africa, Syria, Egypt .... Published in 1805 pp. 128 Google Books

- Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Charles Knight. 1833. p. 53.

- Henry Salt A Voyage to Abyssinia. M. Carey (1816)

- Henry Salt A Voyage to Abyssinia. Published in 1816 pp. 378–382 Google Books

- Henry Salt A Voyage to Abyssinia. Published in 1816 pp. 381 Google Books

- Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge The Penny Cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge: Bassantin – Bloemaart, Volume 4. Published in 1835 pp. 170 Google Books

- Pearce, The Life and Adventures of Nathaniel Pearce, edited by J.J. Halls (London, 1831), vol. 1 p. 70

- Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855–1994, second edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2001), p. 12; Henze, Layers of Time (New York: Palgrave, 2000), p. 122.

- Zewde, Bahru (1991). Bahru Zewde, [London: James Currey, 1991], p. 196. "A History of Modern Ethiopia: 1855–1974". ISBN 0821409727.

- "Peter Gill, p.26 & p.27. "Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia Since Live Aid"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-05-16. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- Mesfin Wolde Mariam, "Rural Vulnerability to Famine in Ethiopia: 1958-77". ISBN 0946688036.

- de Waal 1991, p. 4–6.

- Young 2006, p. 132.

- "Peter Gill, page.43 "Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia Since Live Aid"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-05-16. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- "Peter Gill, page.44 "Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia Since Live Aid"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-05-16. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- Giorgis, Dawit Wolde (1989). Dawit Wolde Giorgis, "Red Tears: War, Famine, and Revolution in Ethiopia". ISBN 0932415342.

- de Waal 1991, p. 5.

- Buzuayeu, Wondimagegn (2006). Ashura - a Festival in al-Negash Mosque. Mekelle, Ethiopia: Mekelle University.

- Bauer, Franz (1985). Household and Society in Ethiopia, an Economic and Social Analysis of Tigray Social Principles and Household Organization. East Lansing, MI.

- Smidt, Wolbert (2005). "Selbstbezeichnungen von Tegreññ-Sperchern (Habäša, Tägaru u.a.)". Studia Semitica et Semitohamitica, Fetschrift Rainer Voigt: 385–404.

- "Tigrinya". Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- "Country Level". 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia. CSA. 13 July 2010. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Leslau, Wolf (1941) Documents Tigrigna (Éthiopien Septentrional): Grammaire et Textes. Paris: Librairie C. Klincksieck.

- "Countries and their Cultures- Tigray". Countries and their Cultures.

- "Ethiopian Treasures- Culture". Ethiopian Treasures.

- "Tihlo". Nutrition for the world.

- Africa Insight, Volumes 23-24. Africa Institute. 1993. p. 187. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- "Together for a healthier world", Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO's General Director

- Herbert Weld Blundell, The Royal chronicle of Abyssinia, 1769–1840, (Cambridge: University Press, 1922), pp. 384–390

- Gebru Tareke, The Ethiopian Revolution: War in the Horn of Africa (New Haven: Yale University, 2009), p. 105 ISBN 978-0-300-14163-4

- Ph.D, Mussie Tesfagiorgis G. (29 October 2010). Eritrea. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598842326 – via Google Books.

- Favali, Lyda; Pateman, Roy (18 June 2003). Blood, Land, and Sex: Legal and Political Pluralism in Eritrea. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253109842 – via Google Books.

- Tesfagiorgis G., Mussie (2010). Eritrea. ABC-CLIO. p. 281. ISBN 978-1598842319. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Edward Denison, Edward Paice (2007). Eritrea: The Bradt Travel Guide. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 82. ISBN 978-1841621715. Retrieved 3 September 2016.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)