Italian Eritreans

Italian Eritreans (or Eritrean Italians) are Eritrean-born descendants of Italian settlers as well as Italian long-term residents in Eritrea.

Church of Our Lady of the Rosary, Asmara, built by the Italians in 1923 and now meeting place of the remaining Eritrean Italians | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 100,000 descendants in 2008[1][2][3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Asmara | |

| Languages | |

| Italian, Tigrinya | |

| Religion | |

| Christian, mostly Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Italians |

History

Their ancestry dates back from the beginning of the Italian colonization of Eritrea at the end of the 19th century, but only after the Second Italo-Abyssinian War of 1935 they settled in large numbers. In the 1939 census of Eritrea there were more than 75,000 Eritrean Italians, most of them (53,000) living in Asmara. Many Italian settlers got out of their colony after its conquest by the Allies in November 1941 and they were reduced to only 38,000 by 1946. This also includes a population of mixed Italian and Eritrean descent; most Italian Eritreans still living in Eritrea are from this mixed group.

Although many of the remaining Italians stayed during the decolonization process after World War II and are actually assimilated to the Eritrean society, a few are stateless today, as none of them were given citizenship unless through marriage or, more rarely, by having it conferred upon them by the State.

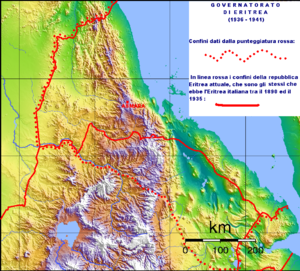

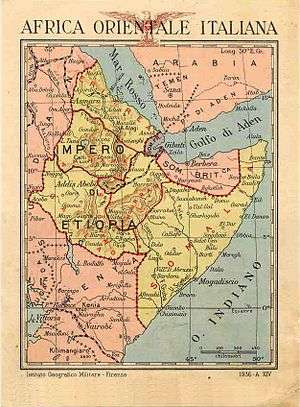

The Italian colony of Eritrea

From 1882 to 1941 Eritrea was ruled by the Kingdom of Italy. In those sixty years Eritrea was populated - mainly in the area of Asmara - by groups of Italian colonists, who moved there from the beginning of the 20th century.

The Italian Eritreans grew from 4,000 during World War I to nearly 100,000 at the beginning of World War II.[4]

The Italians brought to Eritrea a huge development of Catholicism and by the 1940 nearly half the Eritrean population was Catholic, mainly in Asmara where many churches were built.

Italian administration of Eritrea brought improvements in the medical and agricultural sectors of Eritrean society. For the first time in history the Eritrean poor population had access to sanitary and hospital services in the urban areas.

Furthermore, the Italians employed many Eritreans in public service (in particular in the police and public works departments) and oversaw the provision of urban amenities in Asmara and Massawa. In a region marked by cultural, linguistic, and religious diversity, a succession of Italian governors maintained a notable degree of unity and public order. The Italians also built many major infrastructural projects in Eritrea, including the Asmara-Massawa Cableway and the Eritrean Railway.[5]

Benito Mussolini's rise to power in Italy in 1922 brought profound changes to the colonial government in Eritrea. Mussolini established the Italian Empire in May 1936. The fascists imposed harsh rule that stressed the political and racial superiority of Italians. Eritreans were demoted to menial positions in the public sector in 1938.

Eritrea was chosen by the Italian government to be the industrial center of the Italian East Africa. The Italian government continued to implement agricultural reforms but primarily on farms owned by Italian colonists (exports of coffee boomed in the thirties). In the area of Asmara there were in 1940 more than 2000 small and medium-sized industrial companies, concentrated in the areas of construction, mechanics, textiles, electricity and food processing. Consequently, the living standard of life in Eritrea in 1939 was considered one of the best of Africa for the Italian colonists and for the Eritreans.[6]

The Mussolini government regarded the colony as a strategic base for future aggrandizement and ruled accordingly, using Eritrea as a base to launch its 1935–1936 campaign to colonize Ethiopia. In 1939 nearly 40% of the male Eritreans able to fight were enrolled in the colonial Italian Army: the best Italian colonial troops during World War II were the Eritrean Ascari, as stated by Italian Marshall Rodolfo Graziani and legendary officer Amedeo Guillet.[7]

| Year | Italian Eritreans | Eritrea population |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 1000 | 390,000 |

| 1935 | 3100 | 610,000 |

| 1939 | 76,000 | 740,000 |

| 1946 | 38,000 | 870,000 |

| 2008 | 100,000 | 4,500,000 |

Asmara development

-_Hafen_-_Annemarie_Schwarzenbach_-_SLA-Schwarzenbach-A-5-23-129.jpg)

Asmara was populated by a numerous Italian community and the city acquired an Italian architectural look.[8]

Today Asmara is worldwide known for its early 20th-century Italian buildings, including the Art Deco Cinema Impero, "Cubist" Africa Pension, eclectic Orthodox Cathedral and former Opera House, the futurist Fiat Tagliero Building, the neo-Romanesque Church of Our Lady of the Rosary, Asmara, and the neoclassical Governor's Palace. The city is littered with Italian colonial villas and mansions. Most of central Asmara was built between 1935 and 1941, so effectively the Italians designed and enabled the local Eritrean population to build almost an entire city, in just six years.[9]

The city of Asmara had a population of 98,000, of which 53,000 were Italians according to the Italian census of 1939. This fact made Asmara the main "Italian town" of the Italian empire in Africa. In all Eritrea the Italians were 75,000 in that year.

Many industrial investments were done by the Italians in the area of Asmara and Massawa, but the beginning of World War II stopped the blossoming industrialization of Eritrea.[10]

When the British army conquered Eritrea from the Italians in spring 1941, most of the infrastructures and the industrial areas were extremely damaged and the remaining ones (like the Asmara-Massawa Cableway) were successively removed and sent toward India and British Africa as a war booty.

The following Italian guerrilla war was supported by many Eritrean colonial troops until the Italian armistice in September 1943. Eritrea was placed under British military administration after the Italian surrender in World War II.

The Italians in Eritrea started to move away from the country after the defeat of the Kingdom of Italy by the Allies, and Asmara in the British census of 1949 already had only 17,183 Italian Eritreans on a total population of 127,579. Most Italian settlers left for Italy, with others to United States, Middle East, and Australia.

After WWII

The British initially maintained the Italian administration of Eritrea, but the country soon started to be involved in a violent process of independence (from the British in the late 1940s and after 1952 from the Ethiopians, who annexed Eritrea in that year).

During the last years of World War II, Vincenzo di Meglio defended the Italians of Eritrea politically and successively promoted the independence of Eritrea.[11] After the war he was named Director of the "Commitato Rappresentativo Italiani dell' Eritrea" (CRIE). In 1947 he supported the creation of the "Associazione Italo-Eritrei" and the "Associazione Veterani Ascari", in order to get an alliance with the Eritreans favorable to Italy in Eritrea.[12]

As a result of this support, he co-founded the "Partito Eritrea Pro Italia" (Party of Shara Italy) in September 1947, an Eritrean political party favorable to the Italian presence in Eritrea that obtained more than 200,000 inscriptions of membership in one single month. Indeed, the Italian Eritreans strongly rejected the Ethiopian annexation of Eritrea after the war: the Party of Shara Italy was established in Asmara in 1947 and the majority of the members were former Italian soldiers with many Eritrean Ascari (the organization was even backed up by the government of Italy). The main objective of this party was Eritrean independence, but they had a pre-condition that stated that before independence the country should be governed by Italy for at least 15 years (as happened with Italian Somalia).

Since then the Eritrean Italians have diminished as a community and now are reduced to a few hundreds, mainly located in the capital Asmara. The most renowned of them is the professional cyclist Domenico Vaccaro, who won the last stage of the Tour of Eritrea in Asmara in April 2008.[13]

Language and religion

Most Italian Eritreans can speak Italian: there is only one remaining Italian-language school, the Scuola Italiana di Asmara, renowned in Eritrea for its sports activities.[14] Italian is still spoken in commerce in Eritrea.[15]

Until 1975, there were in Asmara an Italian Lyceum, an Italian Technical Institute, an Italian Middle school and special university courses in Medicine held by Italian teachers.[16]

Gino Corbella, an Italian consul in Asmara, estimated that the diffusion of the Italian language in Eritrea was supported even by the fact that in 1959, nearly 20,000 Eritreans were descendants of Italians who had illegitimate sons/daughters with Eritrean women during colonial times.[2][3]

The assimilated Italian Eritreans of the new generations (in 2007 they numbered nearly 900 persons) speak Tigrinya and only a bit of Italian or speak Italian as second language.

Nearly all are Roman Catholic Christians of the Latin Rite, while some are converts to other denominations of Christianity.

Prominent Italian Eritreans

- Vincenzo Di Meglio, doctor at Asmara hospital during the later years of Italian rule, and appointed Director of the C.R.I.E (Comitato Rappresentativo degli Italiani dell’Eritrea), the main association of Italians in Eritrea during British rule. Dr. Di Meglio was one of the main opposers in Eritrea of the British attempt in 1947 to divide Eritrea between Sudan and Ethiopia, a British plot to increase their influence in the region. He obtained the dismissal of this project by the United Nations with his continuous pressure on UN Latin-American representatives (like those of Haiti): the proposal was rejected by a margin of just one vote -that of Haiti- and so Eritrea was not divided between Sudan and Ethiopia. He was later unsuccessful -as a representative of pro-independence Eritrean organizations- when he spoke at the United Nations assembly in New York against the annexation of Eritrea by Ethiopia, as a federated province, in 1950. At the UN, Vincenzo Di Meglio promoted in agreement with the Italian government the idea of "Trustee Administration" by Italy of an independent Eritrea, akin to that of Somalia.

- Ferdinando Martini, the first Governor of the Italian Eritrea. In 1897 he established the Capital of the colonia primogenita ("first-born colony", as Eritrea was called by the Italians) in temperate Asmara, moving the Italian Administration away from hot, equatorial Massawa. During ten years as governor, Fernando Martini built many infrastructures in Asmara (like the present Presidential Palace).

- Luciano Violante, former President of the Italian chamber of Deputies.

- Bruno Lauzi, singer-songwriter.

- Italo Vassalo, footballer.

- Lara Saint Paul, designer.

- Marina Colasanti, writer.

- Remo Girone, actor.

- Melissa Chimenti, actress.

- Ines Pellegrini, actress.

- Vittorio Longhi, Italian journalist and activist of Eritrean origin. He is the grandson of an Italian Eritrean activist, who was shot dead by the Shifta terrorists in Asmara in 1950 because of his commitment for the indipendente of Eritrea from Ethiopia.[17]

See also

- Asmara under Italy

- Asmara President's Office

- Cinema Impero

- Italian Eritrea

- Eritrean Ascari

- Fiat Tagliero Building

- Italian East Africa

- Italian Empire

- Tour of Eritrea

- Italian language in Eritrea

- Asmara circuit

Notes

- The Italian Ambassador stated at the 2008 Film Festival in Asmara that nearly 100,000 Eritreans in 2008 have Italian blood, because they have at least one grandfather or great-grandfather from Italy

- http://www.camera.it/_dati/leg13/lavori/stampati/sk6000/relazion/5634.htm Descendants of Italians in Eritrea (in Italian)

- http://babelfish.yahoo.com/translate_url?trurl=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.camera.it%2F_dati%2Fleg13%2Flavori%2Fstampati%2Fsk6000%2Frelazion%2F5634.htm&lp=it_en&.intl=us&fr=yfp-t-501 Descendants of Italians in Eritrea (in English)

- http://www.ilcornodafrica.it/rds-01emigrazione.pdf Essay on Italian emigration to Eritrea (in Italian)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-02-03. Retrieved 2008-11-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Ompekning pågår - FS Data". alenalki.com.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2008-11-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Chapter Eritrea: Italian architecture in Asmara (in Italian)" (PDF).

- "Reviving Asmara". BBC Radio 3. 2005-06-19. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

- Italian industries and companies in Eritrea Archived 2009-04-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Franco Bandini. Gli italiani in Africa, storia delle guerre coloniali 1882-1943 p. 67

- "Nuova pagina 1". www.ilcornodafrica.it.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-10-03. Retrieved 2008-11-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Information about the 2008 Tour of Eritrea

- "Scuoleasmara.it".

- "About this Collection - Country Studies" (PDF).

- http://www.ilchichingiolo.it/cassetto26.htm Memories 1968–1976 of Lino Pesce, an Italian School Director in Asmara (in Italian)

Bibliography

- Bandini, Franco. Gli italiani in Africa, storia delle guerre coloniali 1882-1943. Longanesi. Milano, 1971.

- Bereketeab, R. Eritrea: The making of a Nation. Uppsala University. Uppsala, 2000.

- Killinger, Charles. The History of Italy. Greenwood Press. 2002.

- Lowe, C.J. Italian Foreign Policy 1870–1940. Routledge. 2002.

- Negash, Tekeste. Italian colonialism in Eritrea 1882–1941 (Politics, Praxis and Impact). Uppsala University. Uppsala, 1987.

- Shillington, Kevin. Encyclopedia of African History. CRC Press. London, 2005. ISBN 1-57958-245-1

External links

- Website of the Italians of Eritrea (in italian)

- Old photos of Italian Eritreans

- Website with photos of Italian Asmara

- Website of the Italian school of Asmara (in italian)

- Italian Art-Deco architecture of Asmara

- Postcards of Italian Asmara

- Website with documents, maps and photos of the Italians in Eritrea (in Italian)

- Travel to Asmara in 2008

- Detailed map of Eritrea in 1936 (click on the sections to enlarge)

- "1941-1951 The difficult years" (in Italian)

- Italian industries and companies in Eritrea

- Italian Emigration to Eritrea (in Italian)

- Eritrea—Hope For Africa’s Future