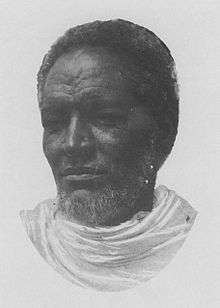

Bahta Hagos

Bahta Hagos (Ge'ez: ባህታ ሓጎስ) was Dejazmach of Akkele Guzay, and retrospectively considered an important leader of Eritrean resistance to foreign domination specifically against northern Ethiopian and Italian colonialism.[1][2] He was born into a rich peasant family, his father Hagos Andu of the Tsena-Degle from Akkele Guzay in the mid-19th century in the town of Segheneyti and was killed in the Battle of Halai against the Italian Colonial Army on December 19, 1894.[1][3][4]

Early fame

Bahta originally gained recognition in 1875 when he killed Embaye Araya son of Rasi Araya, an Ethiopian Governor, in a skirmish precipitated by raiding of the area.[2][5] Bahta and other Eritrean tribal leaders were in constant conflict with the Ethiopian forces under Ras Alula and Yohannes (himself a Tigrian); for example, despite the best efforts of Ras Alula's lieutenant Balatta Gabru in 1880, Bahta evaded capture and later that year allied himself with the Egyptian garrison at Sanhit (latter Keren).[6] In 1885, as an Italian colonial presence replaced the defeated Egyptians, and their control of Massawa, Bahta moved to ally himself with them and their General, later provincial governor Oreste Baratieri. This was done in the hope that Eritreans would be able to maintain a certain amount of independence, at least more so than under Ethiopian influence.[2] As a consequence, Bahta came to control Akkele Guzay, and by 1889 his own forces formed an important flank in the Italian moves to create the Colony of Eritrea.[7] He fought alongside the Italians against the Mahdists at the Battle of Agordat in December, 1893.

However Bahta became increasingly frustrated with the conduct of the Italian Colonial Government and their soldiers, particularly the expropriation of land from the clergy.[8] He understood that Menelik was consolidating his power to the south with plans to displace the Italians. In June 1894, he, along with Ras Mengesha Yohannes, Ras Alula, and Ras Woldemikael Selomon traveled to Addis Ababa to seek forgiveness from the Negus for their dealings with Baratieri.[9] Menelik forgave them and offered Mengesha the crown of Tigray in exchange for his loyalty and help in evicting the Italians. The Tigrian leaders plotted against Baratieri while maintaining a guise of friendship with him. Bahta even led an army into the western province of Shiray on the pretext of fighting the Mahdists, but instead subjugated Kitet and started recruiting an even larger army.

Rebellion against the Italians

In December 1894, Bahta unilaterally led his force of 1,600 men in direct revolt against the Italians, although he claimed support of Mengesha. He captured the Italian administrator at Segheneyti, which was then the capital of the province, and declared an independent Akkele Guzay. He proclaimed himself "An avenger of rights trampled on by the Italians".[10] and also said "the Italians curse us, seize our land; I want to free you... let us drive the Italians out and be our own masters."[11] On the 15th, the telegraph wires were cut from Segheneyti to Asmara, which the Italians had occupied since 1889, in order to give himself time to mobilize the population and bring Mengesha into the conflict. Baratieri immediately suspected Mengesha and ordered Major Toselli and his battalion to move on Segheneyti.

Upon arrival, the Major entered negotiations with Bahta, who stalled him with excuses and promises of loyalty. The Italian reinforcements started to arrive and by the evening of the 17th Toselli had 1500 men and two artillery pieces. He went to move against Bahta the following morning, but found him gone. Bahta had secretly abandoned Segheneyti in the night and had moved his force north against the Italian garrison of 220 men at the small fort of Halay, commanded by Captain Castellazzi. Toselli correctly guessed this was Bahta's plan, and marched his men towards Halay.

Bahta called for Castellazzi to surrender and abandon the fort. Negotiations continued until 13:30, when Bahta's patience came to an end and the attack was ordered. Low on ammunition, the Italians held out until 16:45, when the situation became critical. Toselli's forces arrived at that moment, and launched an attack on Bahta's rear. Bahta was killed in the attack, and his forces fled, many joining Mengesha. Mengesha's army would lose at the Battle of Coatit, but Menelik would soon commit his forces, and destroy the Italians at the Battle of Adwa, ending their colonial hopes for Ethiopia.

Burial

Because of his influence, after his death his burial was banned by the Italian Colonial government.[12] They feared that his memorial would be nexus for further rebellion. His body was secretly buried at Halay, and later moved to Segheneyti in 1953. In 2007 he was interred once more in a newly constructed memorial with an honor guard in memory of his struggle.[12]

References

- Akyeampong, E.K.; Gates, H.L. (2012). Dictionary of African Biography. 6. OUP USA. p. 350. ISBN 9780195382075. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- Killion, Tom (1998). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-3437-5.

- Caulk, R.A.; Zewde, B. (2002). "Between the Jaws of Hyenas": A Diplomatic History of Ethiopia, 1876-1896. Isd. p. 433. ISBN 9783447045582. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- Favali, L.; Pateman, R. (2003). Blood, Land, and Sex: Legal and Political Pluralism in Eritrea. Indiana University Press. p. 106. ISBN 9780253109842. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- Caulk, RA. "Bad men of the Borders: Shum and Shifta in North Ethiopia in the 19th century". 2nd Annual Seminar of Department of History.

- Erlich, Haggai (1996). Ras Alula and the Scramble for Africa. Lawrenceville: Red Sea. p. 33. ISBN 1-56902-029-9.

- Erlich, Ras Alula, pp. 149, 165

- Marcus, Harold G. (1995). The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia 1844-1913. Lawrenceville: Red Sea Press. pp. 154f. ISBN 1-56902-010-8.

- Henze, Paul B. (2000). Layers of Time, A History of Ethiopia. New York: Palgrave. p. 165. ISBN 0-312-22719-1.

- Pankhurst, Sylvia (1952). "Eritrea on the Eve: the Past and Future of Italy's 'first-born' colony. Ethiopia's Ancient Sea Province". New Times and Ethiopia News.

- Caulk, Richard (1986). "13. 'Black snake, white snake': Bahta Hagos and his revolt against Italian overrule in Eritrea, 1894". In Donald Crummey (ed.). Banditry, Bahta Hagos is a real Tiger of Great Akele Guzay Rebellion, & Social Protest in Africa. African Writers Series. Heinemann. ISBN 0-435-08011-3.

- "Skeletal Remains Of Degiat Bahta Hagos Laid To Rest" (PDF). Eritrea Profile. Ministry of Information. 2007-03-10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-12. Retrieved 2007-03-11.

Further reading

- TEKESTE, Negash (1986): No Medicine for the Bite of a White Snake: Notes on Nationalism and Resistance in Eritrea, 1890–1940, University of Uppsala. ISBN 91-7106-250-5

- MELLI, B (1899): La colonia Eritrea dalle sue origini fino al 1. marzo 1899, Luigi Battei. (Italian)

- BERKELEY, G. F.-H (1902): The campaign of Adowa and the rise of Menelik. Reprint, Negro University Press. ISBN 0-8371-1132-3