Lost Generation

The Lost Generation was the social generational cohort that came of age during World War I. "Lost" in this context refers to the "disoriented, wandering, directionless" spirit of many of the war's survivors in the early postwar period.[1] The term is also particularly used to refer to a group of American expatriate writers living in Paris during the 1920s.[2][3][4] Gertrude Stein is credited with coining the term, and it was subsequently popularized by Ernest Hemingway who used it in the epigraph for his 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises: "You are all a lost generation".[5][6]

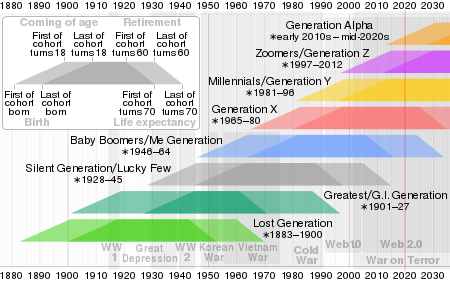

| Part of a series on |

| Major generations of the Western world |

|---|

Timeline of major demographic cohorts since the late-nineteenth century with approximate dates and ages |

In a more general sense, the Lost Generation is considered to be made up of individuals born between 1883 and 1900.[7] The last person known to have been born in the 19th century died in 2018.[8]

In literature

In his memoir A Moveable Feast (1964), published after Hemingway's and Stein's deaths, Hemingway writes that Stein heard the phrase from a French garage owner who serviced Stein's car. When a young mechanic failed to repair the car quickly enough, the garage owner shouted at the young man, "You are all a "génération perdue."[9]:29 While telling Hemingway the story, Stein added: "That is what you are. That's what you all are ... all of you young people who served in the war. You are a lost generation."[9]:29 Hemingway thus credits the phrase to Stein, who was then his mentor and patron.[10]

The 1926 publication of Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises popularized the term; the novel serves to epitomize the post-war expatriate generation.[11]:302 However, Hemingway later wrote to his editor Max Perkins that the "point of the book" was not so much about a generation being lost, but that "the earth abideth forever."[12]:82 Hemingway believed the characters in The Sun Also Rises may have been "battered" but were not lost.[12]:82

Consistent with this ambivalence, Hemingway employs "Lost Generation" as one of two contrasting epigraphs for his novel. In A Moveable Feast, Hemingway writes, "I tried to balance Miss Stein's quotation from the garage owner with one from Ecclesiastes." A few lines later, recalling the risks and losses of the war, he adds: "I thought of Miss Stein and Sherwood Anderson and egotism and mental laziness versus discipline and I thought 'who is calling who a lost generation?'"[9]:29–30

Literary themes

The writings of the Lost Generation literary figures often pertained to the writers' experiences in World War I and the years following it. It is said that the work of these writers was autobiographical based on their use of mythologized versions of their lives.[13] One of the themes that commonly appears in the authors' works is decadence and the frivolous lifestyle of the wealthy.[14] Both Hemingway and Fitzgerald touched on this theme throughout the novels The Sun Also Rises and The Great Gatsby. Another theme commonly found in the works of these authors was the death of the American dream, which is exhibited throughout many of their novels.[15] It is particularly prominent in The Great Gatsby, in which the character Nick Carraway comes to realize the corruption that surrounds him.

Other uses

The term is also used in a broader context for the generation of young people who came of age during and shortly after World War I. Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe define the Lost Generation as the cohort born from 1883 to 1900, who came of age during World War I and the Roaring Twenties.[16] In Europe, they are mostly known as the "Generation of 1914", for the year World War I began.[17] In France, the country in which many expatriates settled, they were sometimes called the Génération du feu, the "(gun)fire generation". In Great Britain, the term was originally used for those who died in the war,[18] and often implicitly referred to upper-class casualties who were perceived to have died disproportionately, robbing the country of a future elite.[19] Many felt that "the flower of youth and the best manhood of the peoples [had] been mowed down,"[20] for example such notable casualties as the poets Isaac Rosenberg, Rupert Brooke, Edward Thomas and Wilfred Owen,[21] composer George Butterworth and physicist Henry Moseley.

Notable figures

Notable figures of the Lost Generation include F. Scott Fitzgerald,[22] Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, T. S. Eliot,[23] Ezra Pound, Jean Rhys[24] and Sylvia Beach.[25]

See also

- Generation#List of named generations

- Lost Decade (disambiguation)

References

- Hynes, Samuel (1990). A War Imagined: The First World War and English Culture. London: Bodley Head. p. 386. ISBN 0 370 30451 9.

- Madsen, Alex (2015). Sonia Delaunay: Artist of the Lost Generation. Open Road Distribution. ISBN 9781504008518.

- Fitch, Noel Riley (1983). Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation: A History of Literary Paris in the Twenties and Thirties. WW Norton. ISBN 9780393302318.

- Monk, Craig (2010). Writing the Lost Generation: Expatriate Autobiography and American Modernism. University of Iowa Press. ISBN 9781587297434.

- Hemingway, Ernest, 1899-1961. (1996). The sun also rises. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0684830515. OCLC 34476446.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Monk, Craig (2004). Writing the Lost Generation: Expatriate Autobiography and American Modernism. Iowa City: University of Iowa. p. 1.

- "Time use of millennials v. non-millennials". 22 December 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- Lekach, Sasha (16 September 2017). "World's oldest person dies, giving title to Japanese supercentenarian". TravelWireNews. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Hemingway, Ernest (1996). A Moveable Feast. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-82499-X.

- Mellow, James R. (1991). Charmed Circle: Gertrude Stein and Company. New York: Houghton Mifflin. p. 273. ISBN 0-395-47982-7.

- Mellow, James R. (1992). Hemingway: A Life Without Consequences. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-37777-3.

- Baker, Carlos (1972). Hemingway, the writer as artist. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01305-5.

- "Hemingway, the Fitzgeralds, and the Lost Generation: An Interview with Kirk Curnutt | The Hemingway Project". www.thehemingwayproject.com. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- "Lost Generation | Great Writers Inspire". writersinspire.org. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- "American Lost Generation". InterestingArticles.com. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- Howe, Neil; Strauss, William (1991). Generations: The History of Americas Future. 1584 to 2069. New York: William Morrow and Company. pp. 247–260. ISBN 0-688-11912-3.

- Wohl, Robert (1979). The generation of 1914. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-34466-2.

- "The Lost Generation: the myth and the reality". Aftermath – when the boys came home. Archived from the original on 1 December 2009. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- Winter, J. M. (November 1977). "Britain's 'Lost Generation' of the First World War" (PDF). Population Studies. 31 (3): 449–466. doi:10.2307/2173368. JSTOR 2173368.

- Rosa Luxemburg et al., "A Spartacan Manifesto, The Nation, March 8, 1919, pp. 373-374

- "What was the 'lost generation'?". Schools Online World War One. BBC. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- Lapsansky-Werner, Emma J. United States History: Modern America. Boston, MA: Pearson Learning Solutions, 2011. Print. Page 238

- Esguerra, Geolette (9 October 2018). "Sartre was here: 17 cafés where the literary gods gathered". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Thompson, Rachel (25 July 2014). "A Literary Tour of Paris". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Monk, Craig (2010). Writing the Lost Generation: Expatriate Autobiography and American Modernism. University of Iowa Press.

Further reading

- Doyle, Barry M. "Urban Liberalism and the ‘lost generation’: politics and middle class culture in Norwich, 1900–1935." Historical Journal 38.3 (1995): 617-634. in Great Britain.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

- Fitch, Noel Riley (1985). Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation: A History of Literary Paris in the Twenties and Thirties. Norton. ISBN 0-393-30231-8.

- Winter, Jay M. "Britain's ‘Lost Generation’ of the First World War." Population Studies 31.3 (1977): 449–466. online, covers the statistical and demographic history.